Wisconsin Cities Look to Basic Income to Close Racial, Other Wealth Gaps

Following the lead of presidential candidate Andrew Yang, cities in Wisconsin and elsewhere are providing residents a basic income — will the trend grow?

Wisconsin Watch

August 16, 2021

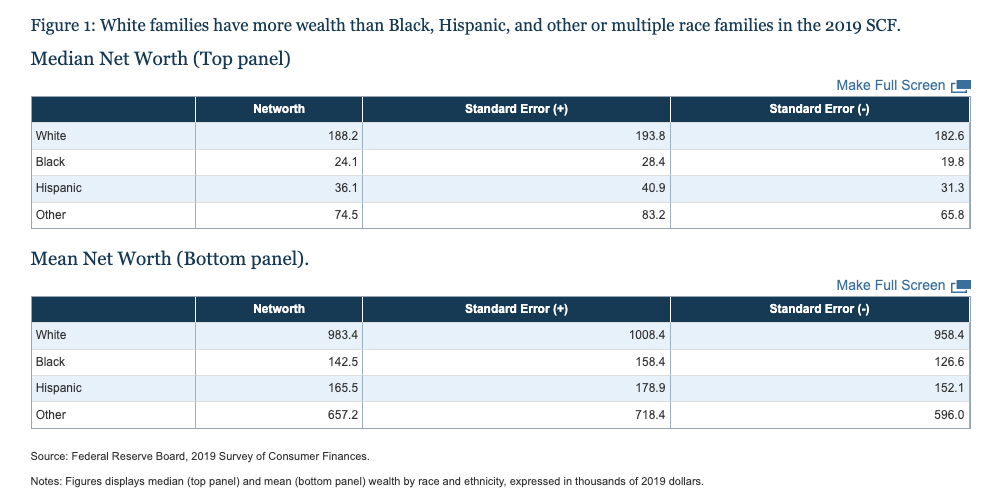

The typical white family has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family and five times the wealth of the typical Hispanic family, according to the Federal Reserve Board's 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances. That survey shows long-standing and substantial wealth disparities between families in different racial and ethnic groups changed little since the last survey in 2016. (Credit: Claire DeRosa / Wisconsin Watch)

By Harrison Freuck and Zhen Wang, Wisconsin Watch

Towanda Perkins is a single mother with two grown sons. She works as an office manager at a nonprofit organization in Milwaukee.

During the pandemic, she has seen many mothers with children who have lost their jobs and been evicted by landlords. Perkins is expecting to see more homelessness once the temporary halt on certain evictions issued by the CDC — extended to Oct. 3 — ends.

Between June and November of last year, the national poverty rate increased by 2.4% overall — but 3.1% for Black Americans, according to economists from the University of Chicago and the University of Notre Dame.

Such inequity did not arrive with the pandemic. It is a long-standing feature of American life, with Black residents earning and owning just a fraction of what white residents do, creating a society fractured along racial and economic lines.

Entrepreneurs, scholars and politicians, including 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, have proposed programs such as guaranteed income or universal basic income to alleviate this persistent wealth and income disparity. Such programs give all residents, or in some cases just low-income residents, a set income to be used however recipients see fit as a way to meet basic needs.

In fact, the Child Tax Credit in President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan, which gives parents up to $3,600 per child, has been called a “baby step” toward a guaranteed income program.

Perkins knows from personal experience what many low-income African-Americans families are facing — and how such a basic income program could change their lives.

She participated in the New Hope Project, an experiment conducted in Milwaukee in the mid-1990s. In 1994, she was a 23-year-old single mother, six months pregnant with her second child. The program helped her find a job and to get off welfare. Perkins said the support helped her set a new course for her life.

Today, in addition to counseling prospective homeowners, she works as an office manager overseeing payroll for the Dominican Center, a nonprofit social service agency that works with residents of Milwaukee’s Amani neighborhood.

“It was a big help because I felt like without the New Hope Project, I don’t know where I’d be,” Perkins said. “That program — it helped me to this day.”

Basic income programs proliferate

Madison, Milwaukee and Wausau are just three of 50-plus U.S. cities participating in the Mayors for a Guaranteed Income program, which was founded on the belief that “in the richest country in the world, no one should live in poverty, and that we can afford an income floor for all who need it.”

“In the last decade, (UBI) has emerged not as a magic bullet solution, but as part of the way to address structural unemployment and poverty in an array of different social contexts,” according to Stephen Young, a University of Wisconsin-Madison assistant professor who studies basic income programs in the United States and worldwide.

Young said countries such as Finland and Canada have recently tested the idea of UBI. Those experiments have never been truly universal — which would involve providing a regular cash payment for all citizens, unconditionally and regardless of income level.

In reality, programs have targeted specific groups of people, such as those below the poverty line, with a stipend on top of whatever they may already earn. These are often referred to as guaranteed basic income programs.

Stockton program sees success

Former Stockton, California Mayor Michael Tubbs launched that city’s program in February 2019. The Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration (SEED) gave 125 Stocktonians with an income under $46,033 — the city’s median income — $500 per month for 24 months. The program was funded with more than $3 million in private donations, including $1 million from the Economic Security Project.

SEED released its first-year data in March. Erin Coltrera, one of the authors of the preliminary analysis, said the numbers show the program worked.

“It was a success, and it helped people,” Coltrera said.

She said one of the biggest issues that low-income Stockton families and many Americans face is that they are unable to meet basic needs. The 2008 financial crisis, stagnant wages and increasing living costs have made many feel uncertain or unable to consistently access cash.

Tomas Vargas participated in the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration program in Stockton, California. Vargas lives with his wife and two children in Stockton, where he works in manufacturing. He says the extra $500 a month allowed him to take advantage of opportunities and have less stress about day-to-day issues. (Credit: Courtesy of Snap Jackson / SEED)

Researchers hypothesized that a regular payment would reduce income volatility, enabling recipients to make life choices, set goals and take risks. One key finding in Stockton was an increase in full-time employment among recipients across the first year, from 28% to 40% — weakening the common critique that guaranteed income would result in fewer people working.

The extra money also allowed recipients to buy small luxuries like birthday cakes and afforded free time to spend with friends or family, the report found. Additionally, the supplementary income stabilized households where the money for necessities routinely runs out.

At the start of the program, only 25% of recipients could pay for an unexpected expense without borrowing money. A year into the program, 52% could pay for such an expense without going into debt.

“I don’t think anyone on the team thought that it would play out that drastically,” Coltrera said.

Wisconsin joins basic income movement

Similar programs in Madison, Milwaukee and Wausau are still in the planning stages. While none of them has fully laid out how its guaranteed income program would work, the source of the funding is set: Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, a well-known proponent of guaranteed income. He gifted $15 million to Mayors for a Guaranteed Income to help fund programs across the country.

Wausau’s program expects to receive $100,000, and Madison expects $600,000. The city has also raised another $300,000 from local donors, totaling $900,000. Details of Milwaukee’s program are not yet publicly known; Mayor Tom Barrett announced the city’s plan to participate in late March.

Wausau Mayor Katie Rosenberg said the city is searching for additional funding from local organizations to aid more residents.

Madison Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway said the city’s program will likely include at least 125 families with children who will receive $500 per month for a year, but eligibility for the program stays “relatively broad.”

Madison Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway has proposed a basic income program for low-income city residents. The $900,000 plan calls for at least 125 families with children to receive $500 per month for a year. Here, Rhodes-Conway is seen at a press conference in Madison on June 8, 2021. (Credit: Will Cioci / Wisconsin Watch)

In Wausau, Rosenberg plans to target the working poor. Rosenberg said she wants to supplement the program with financial literacy classes through local organizations such as United Way and with other welfare programs such as BadgerCare.

“We’re almost at 15% poverty in Wausau. (The council) wants to address homelessness and some of these other things. So, this program, once we started hearing about it, made sense,” Rosenberg said. “It might only tackle a few individuals, maybe it’s only 18 or maybe it’s only 15, but it will still take steps toward tackling that problem of poverty and homelessness in our city.”

Coltrera said guaranteed income programs aim to show that poverty isn’t caused by poor people doing something wrong, but because of systems stacked against them. In fact, the wealth gap between Black households and their white counterparts has been consistent — and striking.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found that the median Black households earned half as much as their white household counterparts in 2016. The median Black household has less than 15% of the wealth of their white counterparts.

Based on data from 1949 to 2016, the agency found that “Over seven decades … no progress has been made in closing the black-white income gap. The racial wealth gap is equally persistent and a stark fact of postwar American history. The typical black household remains poorer than 80% of white households.”

The Federal Reserve Board’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances found large disparities between the wealth of white Americans compared to residents of other races. Basic income programs aim to reduce wealth gaps. (Credit: Federal Reserve Board)

Marc Levine, the founding director of the Center for Economic Development at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, said the gap is even larger in some metro areas like Milwaukee, where Black households earned just 42% of the income of their white counterparts in 2018.

Said Coltrera: “We’re trying to shift the narrative away from the idea that if you are poor or if you are experiencing negative financial outcomes that it’s because of a personal choice that you made and that it’s because you failed in the market. Instead, it’s because the market failed. Because the way in which this is set up, is not a question of character, but just a question of circumstance.”

Project short-lived

Perkins was among the 678 participants that the New Hope Project helped using a package of benefits, including a supplementary income, child care services and health insurance. Created by community activists and business leaders, the poverty reduction program ran from August 1994 to December 1998.

In the project report, researchers described the program as a social contract rather than a welfare program because participants had to work at least 30 hours per week to qualify.

A project officer provided Perkins three working opportunities. She picked the one closest to her one-bedroom apartment, a receptionist at West Side Conservation Corp. Adding to her wages, the New Hope Project supplemented her income to put her above the poverty line. She also used the program’s offered child care services.

Towanda Perkins of Milwaukee participated in a basic income program in the mid-1990s. As a single mother of two children, Perkins says the New Hope program helped her enter the workforce by providing access to a job and basic support including child care. “It was a big help because I felt like without the New Hope Project, I don’t know where I’d be … That program — it helped me to this day.” (Credit: Courtesy of Towanda Perkins)

Before enrollment, she received Aid to Families with Dependent Children, a federal monthly cash assistance program that primarily aided single mothers with children under 18. Cash grants varied widely by state; in 1994, a family of three with no earned income received a median of $366 per month. Congress abolished the program in 1996 and replaced it with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, which allowed states to design their own welfare systems that have shrunk cash assistance over the years.

“When I first started off, I started really making money,” Perkins said, allowing her to stop receiving welfare payments.

The job gave her experience with home buying and nonprofits, skills she still uses in her positions today. Meanwhile, she spent more time with her two young boys. She remembered taking them on a bus to the circus, an opportunity she would not have otherwise had.

Her sustainable life lasted for a while, but West Side Conservation Corp. ultimately closed. She lost her job and the child care benefits the New Hope Project offered, circumstances that left her “depressed.”

New Hope offered new start

Perkins initially tried to go back to welfare. Thanks to the social relations she built with the first job, she instead landed a second job a couple of months later, at Housing Resources, Inc., in May 1997.

Perkins moved to a new house, leaving behind the one-bedroom apartment she had shared with her two boys for eight years. She also bought a new car. In 2010, she finished an associate degree in business management.

A study completed five years after the New Hope Project ended found that about one-third of the participants relied on the available community-service jobs during the program. This established a work record that helped them find jobs after the program ended.

Towanda Perkins works as an office manager overseeing payroll for the Dominican Center, seen here, a nonprofit social service agency that works with residents of Milwaukee’s Amani neighborhood. She says the New Hope Project changed her life. Photo taken on July 1, 2021. (Credit: Isaac Wasserman / Wisconsin Watch)

The program was funded by a variety of sources, including local, state and national organizations, as well as by the state of Wisconsin and the federal government. According to another retrospective study, a real-world version of the New Hope Project would cost about $3,308 in 2005 dollars per participant per year in taxpayer costs. That’s about $4,713 today.

Researchers found that among all people who participated in the program, work increased by 9% and average annual earnings increased by $2,500 in 2005 dollars, the equivalent of $3,560 today. It also improved school performance and eased behavioral problems among children in New Hope families, likely decreasing crime rates and indirectly generating large taxpayer benefits, according to the report.

The New Hope project ended in 1998 because the limited funding ran out.

Basic income has long history

The concept of a basic income entered the political realm in the United States in the late 1960s and ’70s. Civil-rights icon the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. endorsed it as an effective solution to reduce poverty. And President Richard Nixon attempted to pass a negative income tax, which would have rewarded working people with government subsidies, allowing them to make more money than people who don’t work.

The popularity of basic income has had a resurgence over the past 10 years, partially driven by Silicon Valley tech moguls. Proponents include Dorsey, Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes and Tesla CEO Elon Musk. Musk said he views it as a solution to address a projected reduction in the demand for human labor as innovation and technology advance. But economist Paul Krugman has criticized this sentiment, explaining that automation is not increasing rapidly enough to justify basic income programs.

Yang, a tech entrepreneur and philanthropist, championed UBI as the centerpiece of his 2020 presidential campaign. After his unsuccessful presidential run, Yang joined a group of 13 Democratic candidates for New York City mayor, where he pushed for the nation’s largest city to give 500,000 people who live in extreme poverty in the city an average of $2,000 a year, or around $167 per month. Yang conceded in late June after finishing fourth in the Democratic primary.

Yang’s efforts — and the pandemic — have pushed the idea of a universal basic income from the margins to the center of political debate. As proof of how far this idea has come: The Trump administration provided two rounds of cash-based stimulus checks to all citizens to support them during the pandemic.

Wisconsin is among a handful of states where local communities have implemented basic income programs to give low-income families a set amount of money each month to meet basic needs and close racial and other income gaps. Programs are in the planning stages in Milwaukee, Madison and Wausau. The Wisconsin State Capitol is seen here on June 11, 2020. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

A study shows those relief measures cut poverty and boosted quality of life for millions of people. Researchers at the University of Michigan found that the cash assistance improved Americans’ financial stability and access to food, while decreasing anxiety and depression. They have also found that those programs had the biggest impact on low-income households and those with children.

Food insufficiency fell by around 41% from late December 2020 to April, and financial instability dropped by 43%. Anxiety and depression symptoms decreased by more than 20%.

The use of direct cash payments continues. Beginning in July, the Biden administration implemented a child tax credit through the American Rescue Plan, giving many families up to $300 per month — or $3,600 a year — for each child under the age of 6, and $3,000 for each child between the ages of 6 and 17. It is set to expire at the end of 2021.

Guaranteed income support split

And while the American Rescue Plan enjoys broad bipartisan support among voters, fewer people endorse the idea of a guaranteed income. Just 45% of people polled by the Pew Research Center last August said they would support a $1,000 per month guaranteed income for all U.S. adults, regardless of whether they are working.

But Young, the UW-Madison researcher, said Biden’s plan has the potential to raise public support for unconditional cash-transfer programs, like the Child Tax Credit.

“I would think that this is exactly the circumstances under which these programs could then become permanent or could expand … beyond that (2021) deadline,” he said. “Because I do think that once people start to get that support, then you can make a political appeal to them.”

Due to the lack of support for a nationwide guaranteed income as a permanent social policy, Coltrera said local case studies had been the only way to garner more support from the public. But the pandemic stimulus programs have offered another way to demonstrate how such a program could work.

“When you’re thinking about scale, playing with this stuff on local levels gives you a chance to innovate, to solve around these problems and to build programs that can then be scaled up without running into those massive issues that were faced by the CARES Act,” Coltrera said.

She also said the Mayors for a Guaranteed Income initiative is “leveraging the political power that urban mayors have.” On the one hand, they have the opportunity to appeal to large constituencies they represent, and on the other hand, states and the federal government must pay attention to what they are saying and doing, she said.

But mayors still must balance between pushing a progressive universal basic income policy and gaining support from the local community.

Stockton legacy mixed

News of the success of the Stockton program, released in March, came too late for that city’s mayor. Tubbs was defeated for re-election in November 2020. Some supporters said Tubbs was defeated by a large online misinformation campaign. But the Rev. Dwight Williams, chairman of the San Joaquin County GOP, said the city’s large homelessness problem and Tubbs’ use of the city’s pilot basic income program to raise his political profile may have turned off voters.

“Some people also felt that (Tubbs) was more interested in a stage that was bigger than Stockton, and that was an issue,” Williams said. “Some people just felt like he was more concerned about using this as a stepping stone, more than trying to deal with some of our issues here in this community.”

Williams said he is skeptical of basic income programs because it is unsustainable, potentially requiring a tax increase. Williams would prefer efforts to improve the local economy, rather than making people more dependent on the government.

“I think the questions that really should be asked are, ‘What can we do to stimulate business? What can we do to get more people incentivized to empower themselves to education?'” Williams said.

Sukhi Samra, left, executive director of the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, talks with then-Mayor Michael Tubbs of Stockton, California. Tubbs and Samra helped pilot the SEED income program in Stockton from February 2019 to February 2021. One key finding in Stockton was an increase in full-time employment among recipients across the first year, from 28% to 40% — weakening the common critique that guaranteed income would result in fewer people working. (Credit: Courtesy of Michael Conti)

But in an April keynote talk for the Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship, Tubbs said SEED was about more than supporting individuals.

“The narrative around poverty and the economy changed in this country,” Tubbs said. “In part, because of storytelling, because we’re able to amplify and lift up the stories of people who look like everyone else, who are working incredibly hard but the economy wasn’t working for them.”

Back in Wisconsin, Rosenberg said she has gotten blowback from Republicans in the Wausau region about the city’s planned guaranteed income program. Rosenberg said some of her constituents believe it’s “a terrible idea” and one step down “a progressive rabbit hole.”

Despite the criticism from conservatives, the idea of guaranteed income may be destined to gain steam over time. Pew found that 67% of people in the 18-29 age range favor such a program.

“As far as political parties, I don’t really care what they have to say about it if it’s good for people,” Rosenberg said. “So, if there’s a way that I can get money to people who need it here, I’m going to do that.”

Critics often say that cash assistance reduces the incentive to work. But Perkins argues the opposite; that such programs offer opportunities, providing single mothers the means to work for a better life for themselves and their children.

“We need somebody to step in to say, ‘Hey, here we’re going to give you some help to push you,'” Perkins said.

This story was produced as part of an investigative reporting class at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication under the direction of Dee J. Hall, Wisconsin Watch’s managing editor. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us