Why One Scientist Has Divergent Views On Wisconsin's Great Lakes Diversions

Supporting one high-profile Great Lakes diversion and opposing another might seem contradictory, but UW-Parkside geosciences professor John Skalbeck clearly sees no tension in his positions.

By Scott Gordon

April 25, 2018

John Skalbeck in front of the Root River screenshot

If it is possible to be a fan of Waukesha’s plan to tap Lake Michigan for drinking water, John Skalbeck is among their ranks. A professor of geosciences at the University of Wisconsin-Parkside in Kenosha, Skalbeck specializes in hydrogeology, a field of study chiefly concerned with groundwater. As city of Waukesha officials worked to convince the governors of the Great Lakes states that their plan was environmentally sound and met the demands of the legally binding Great Lakes Compact, which governs access to the lakes’ vast freshwater resources, Skalbeck argued in favor of it multiple times.

Waukesha got permission to use Lake Michigan water after a long process, which in many ways was the first major test of the Compact and the exceptions it carves out to allow some use of Great Lakes water outside of their drainage basin. The whole idea of the Compact is to keep people from shipping Great Lakes water far afield, whether to Asia or the American Southwest — the exceptions are all about geography and rely on both state governments and a regional body for enforcement.

The city of Waukesha is located entirely outside of the Great Lakes Basin but is in a county that partially straddles its border, and therefore can access the water if its use meets certain strict conditions and secures unanimous approval from the governors of all eight states that border the Great Lakes. Opponents of Waukesha’s bid fear that it sets too loose a precedent for other straddling-county communities who might want to tap into the lakes in the future. Skalbeck, on the other hand, represents as well as anyone the conviction that Waukesha has an environmentally responsible plan and that the eight governors applied the law correctly.

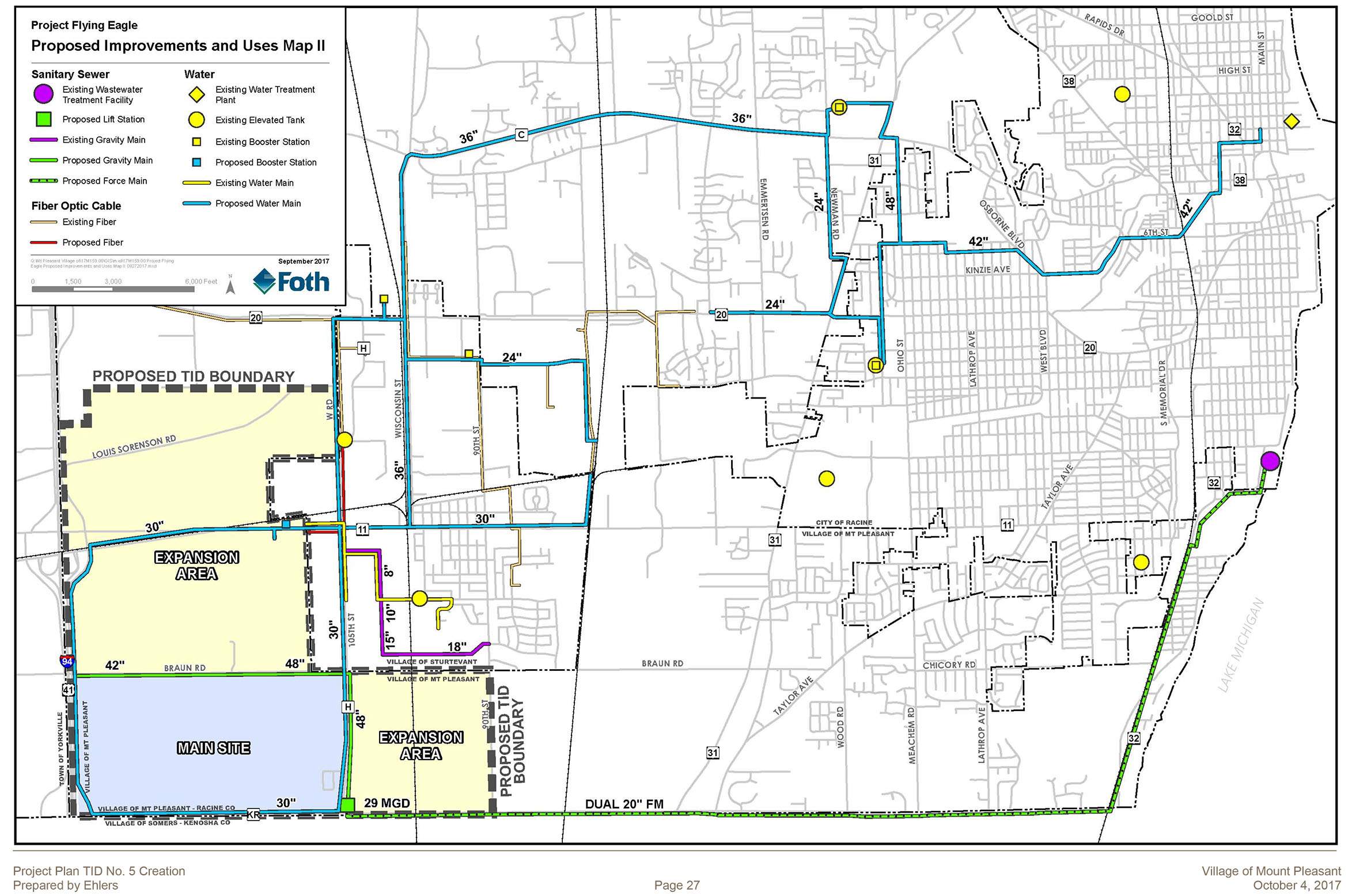

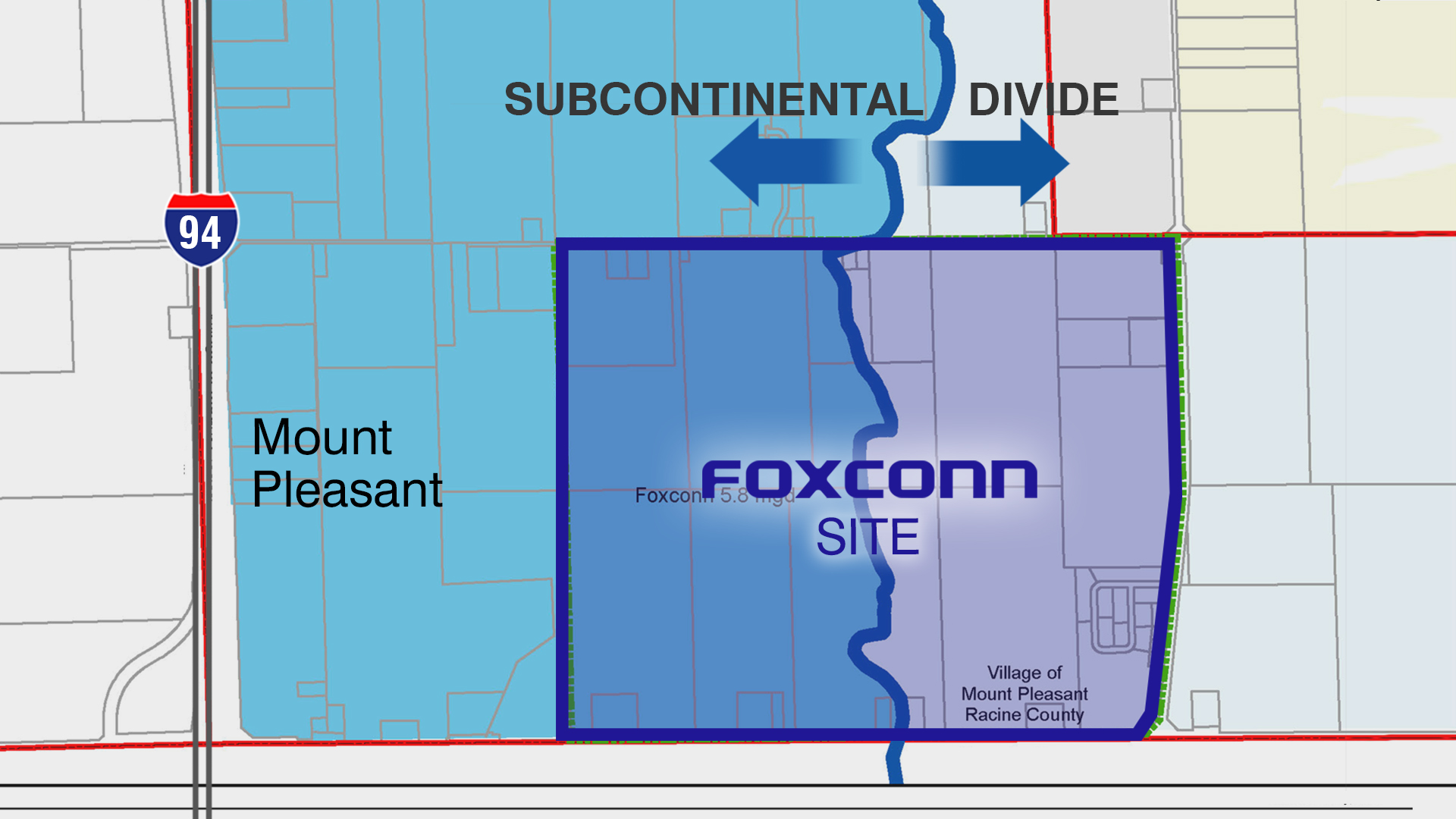

On April 25, 2018, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resourcesapproved a request from the Racine Water Utility to send about 7 million gallons a day to the in-the-works Foxconn site in Mount Pleasant. The Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer has chosen a site that’s partially within and partially outside of the Basin, which means that using water there needs state-level approval and regulation under the Compact. As part of the process of reviewing Racine’s application, the DNR took public comments, both at in-person sessions in the area and through letters sent to the agency.

Skalbeck sent a letter to the DNR, and pulled no punches in his opposition. “Approving the Racine Application to divert Great Lakes water for a single industrial user would set a terrible precedent for future water diversion considerations under the Great Lakes Compact,” he wrote.

Skalbeck’s divergent opinions about the Waukesha and Foxconn diversions comes off as a novel alignment in such politically tribal times, especially given that both projects have the support of Gov. Scott Walker and raised the ire of environmental groups.

The position Skalbeck has staked out also sheds a light on how complex the science and politics of Great Lakes water really are, and how many open questions surround these issues. He explained his perspective on the Foxconn proposal in an April 20 report on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now.

“The provision that I have a problem with [in] the Racine application is over the intent for it to be public use,” Skalbeck said. “This ask is primarily for Foxconn, so, a single commercial user…it seems like it might be straining the intent of the law, the Compact.”

All the water Racine plans to pump to the Foxconn site is indeed for industrial and commercial use, and mostly by one company. It’s a commonly raised point from the environmental groups who oppose the proposed diversion.

The Compact treats the water in the Great Lakes as a public trust. Industry can use it — and in fact it’s common for industrial users to simply purchase water from public utilities — but drinking water for the Basin’s 34 million residents is the explicit priority. The agreement states that diversions of water are to be for “Public Water Supply Purposes,” which are defined as “largely” for residential use. As for what “largely” means, the text of the Compact is inconclusive, so at this point it’s not really clear how these requirements would be applied to a complex real-world situation.

In his letter to the DNR, Skalbeck wrote that Racine’s application “distorts the notion that the diverted water is to be ‘distributed to the public.'”

Essentially, Racine argued that even though the Foxconn diversion area is entirely for industrial and commercial use, it still satisfies the Compact’s requirements because the utility’s overall water service area is primarily residential. (It’s possible that new housing will spring up in the diversion area at some point, but Racine’s application didn’t address that.)

Before the DNR announced it would approve the permit, Skalbeck said he anticipated the green light, but thought the “Public Water Supply” issue could spark litigation from other states.

Precedents made and precedents to come

Supporting one high-profile Great Lakes diversion and opposing another might seem contradictory, but UW-Parkside geosciences professor John Skalbeck clearly sees no tension in his positions. Both Waukesha and Racine/Foxconn ultimately come down to properly enforcing the Great Lakes Compact and the requirements it puts around water access. Without its restrictions, he told Here & Now, “there would be a lot more pressure on the Great Lakes as far as supplying water to other areas.”

In his letter to the DNR, Skalbeck made novel argument of the connected the two diversions: Treating the Waukesha decision as setting a justified precedent that the Foxconn proposal would violate. In its years-long bid to source Lake Michigan, Waukesha initially wanted the right to use its water not just for the area its utility already served, but also for new places it might expand service to in the future. Regional officials and members of the public pushed back, and ultimately Waukesha reduced the amount of Lake Michigan water it requested and agreed to keep that use within its preexisting geographic service area.

Moreover, the amount of water approved for Waukesha, Skalbeck has pointed out, is infinitesimal compared to the overall volume of Lake Michigan, and it will be discharged back into the Great Lakes Basin. (This comparison accurately reflects the current scientific consensus that human water use in the Great Lakes is nowhere near intense enough to diminish the overall water supply given other environmental factors.) However, both Skalbeck and Waukesha officials have amplified the discharge factor a bit in public statements, as some water inevitably gets used up and cannot be returned, an effect known as consumptive use.

Waukesha’s diversion approval holds the city’s utility to consumptive use standards that are tougher than those required by the Compact, requiring is to return “a daily quantity of treated wastewater equivalent to or in excess of the previous calendar year’s average daily Diversion” — the utility says rainwater and snowmelt entering its sewage system will allow the city to send back a greater volume of water than it takes out of the Basin.

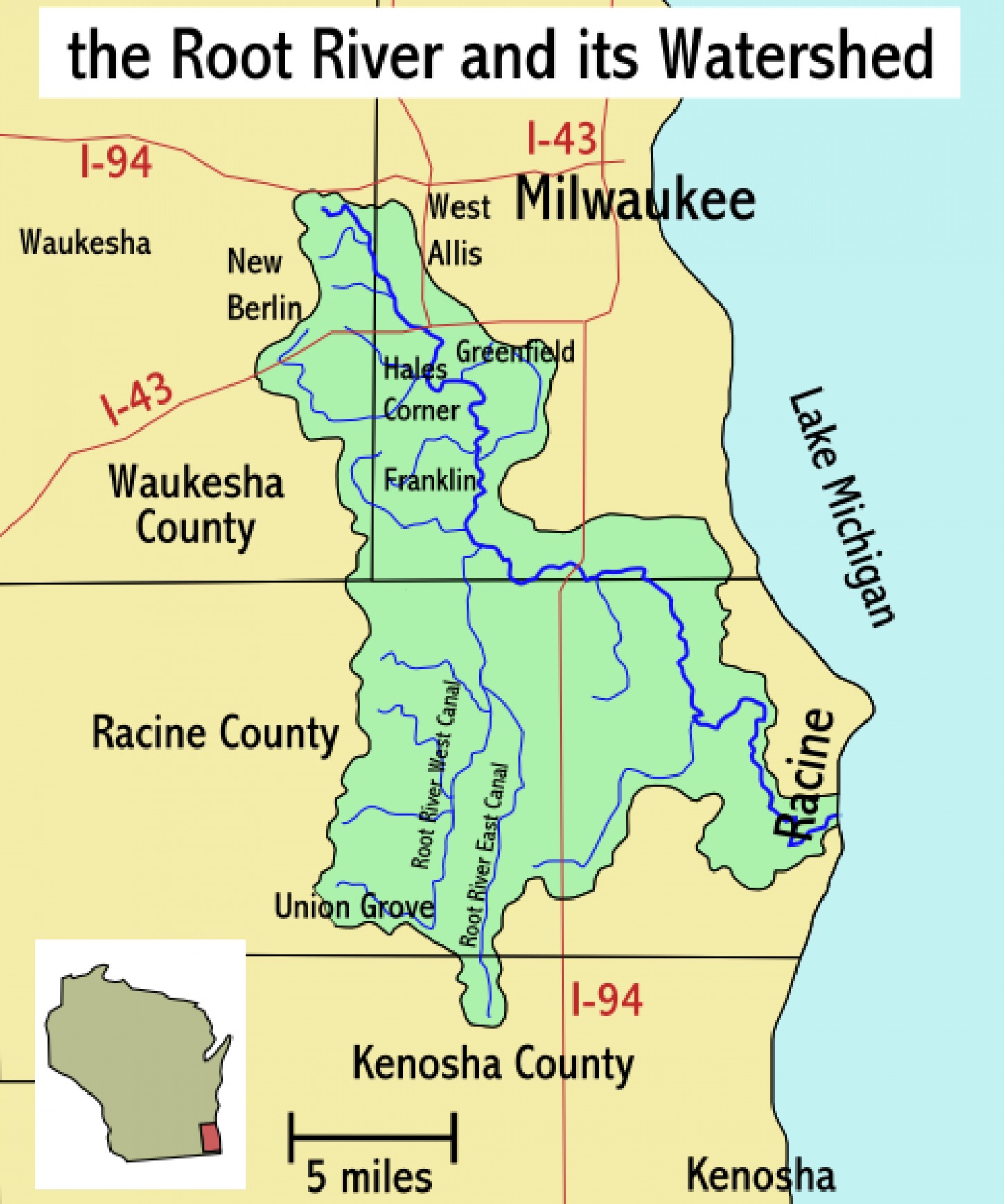

Waukesha’s plan to send treated wastewater back to the Basin through the Root River has upset officials and residents in Racine, where the river empties into Lake Michigan. But Skalbeck argues that the Root needs more water, and this inflow from Waukesha’s water utility is a responsible way to provide it. He also has said that scientific evidence backs up Waukesha’s argument that it doesn’t have a reasonable alternative to using Lake Michigan water, like finding a different groundwater source to replace its current radium-laced supply.

Skalbeck noted in his letter that the terms of Waukesha’s diversion “signals agreement that diverted Great Lakes water can NOT be used for an expanded service area,” and that Racine would be using the Foxconn diversion to extend service to an area that it doesn’t currently supply. (The utility does send water to other areas of the village of Mount Pleasant.) Skalbeck is arguing that it would be incongruent to approve Waukesha’s diversion while limiting that city’s plans to expand its water service area, but allow Racine to expand its service area, largely for the sole benefit of one company.

With his perspective on Waukesha, Skalbeck set himself against most of the state’s most vocal environmental-preservation advocates, including Clean Wisconsin and Milwaukee Riverkeeper, who feared Waukesha hadn’t really exhausted all other options and wouldn’t do enough to limit environmental harm. Yet when it comes to another potentially historic Great Lakes diversion request, this time to serve Foxconn’s LCD screen factory in Mount Pleasant, they’re on the same side of the issue.

Skalbeck wants Foxconn and Racine to tell the public more about what kinds of contaminants could be in the wastewater flowing out of the plant. Large-scale electronics manufacturing will inevitably involve all kinds of pollutants, some of which aren’t common in what Wisconsin already sees from agricultural and industrial sources. However, the diversion application offered little detail about what specific substances Foxconn’s Wisconsin plant would work with, or what specific wastewater treatment processes it would use.

“There was no information in the application about that waste stream will contain,” Skalbeck said.

Industrial water users do have to do “pre-treatment” on their wastewater if it contains contaminants their utility’s treatment plant can’t handle. Racine Water Utility manager Keith Haas told WisContext in March 2018 that he hasn’t yet seen Foxconn’s specific pre-treatment plans, but that he would be in charge of reviewing and approving those plans before the plant discharges one drop of water.

Waukesha’s plan involves discharging wastewater, but that’s mostly residential sewage. For all the environmental problems sewage can create, they are by and large a known quantity that Wisconsin utilities and regulators have dealt with for a long time. On the other hand, the state has little experience with massive electronics fabrication operations, so the water that flows back from Foxconn to Racine to Lake Michigan could introduce different and unexpected challenges.

Water politics that don’t wash

In April 2018, several environmental advocacy groups, under the umbrella of the Compact Implementation Coalition called for the seven other Great Lakes states to get involved in the process of reviewing the Foxconn diversion application. The Coalition considers a water diversion solely for industrial use not allowable under the Compact, and suggests that other signatory states have authority to weigh in on the decision because Mount Pleasant is a community that straddles the basin line. Their demand led to a tit-for-tat exchange with Gov. Scott Walker, who accused the environmentalists of trying to undermine the Foxconn project and pointed out that if the diversion is approved, Racine would be drawing less water overall from Lake Michigan than it did 20 years ago.

Nothing in this spat sheds much light on how the Compact actually works, though. The fact that Racine would withdraw less Lake Michigan water overall than it used to is not relevant to the fact that the city is asking to send water outside the Great Lakes Basin, nor does it affect the question about doing so for entirely industrial and commercial use. Moreover, the Compact largely allows states to regulate diversions to straddling communities, and while largely private use of the diverted water potentially violates its terms, that doesn’t in itself make Racine’s proposal subject to regional review at this time.

The dispute between the environmental groups and Walker muddies the waters, metaphorically. The state has a large amount of discretion in this kind of a diversion process. Now that the DNR has approved the Racine/Foxconn diversion, Wisconsin’s fellow Great Lakes states and, the Compact states, “any aggrieved Person” in the region have the right to bring their grievances to the compact council, and after that, perhaps to court.

Editor’s note: This item was update to provide additional information about the Waukesha diversion’s requirements with regards to consumptive use.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us