Why are many Wisconsin school districts holding referendums?

Dozens of school districts around the state are going to referendum in the 2024 spring election, with local educators seeking support for spending priorities while working within state funding limits.

By Zac Schultz | Here & Now

March 28, 2024

On April 2, many voters across Wisconsin will decide on the future of their local school district.

Sixty-two districts are asking voters to approve an operating referendum, which allows districts to raise their tax levy in order to fund day-to-day operations. The biggest request comes from Milwaukee Public Schools, where they are asking voters to approve $252 million over four years. But the needs vary according to size, with the Juda School District seeking just $500,000 a year.

What’s consistent is that over the past few years, the number of districts going to referendum has increased — and there’s no sign of the trend slowing down.

Inside Fort Atkinson’s schools, things look normal: Kids are reading, learning math, playing instruments.

But things could look dramatically different in the fall if the voters don’t approve the operating referendum on the April 2 ballot.

“This isn’t a referendum that we can live without,” said Rob Abbott, superintendent of the School District of Fort Atkinson. This is his third straight year trying to pass a referendum.

“Two years ago was the first time that the community rejected the operational referendum,” said Abbott. “In that effort, we made it clear that the needs weren’t going to change and that we would need to come back again, which we did last April.

Fort Atkinson had a long record of supporting operating referendums for the schools.

“So last spring, we failed the operational referendum somewhat significantly. And it was really perhaps the first time that we really gave pause to things had really changed,” Abbott said.

The district cut $3.3 million from their budget, including 45 staff positions. Now, they’re asking for $6.5 a year for the next three years to avoid more cuts.

Abbott said just about every district going to referendum is in the same situation.

“This spring or certainly with the next November election cycle,” he said, “districts who aren’t successful are going to be looking at significant reductions.”

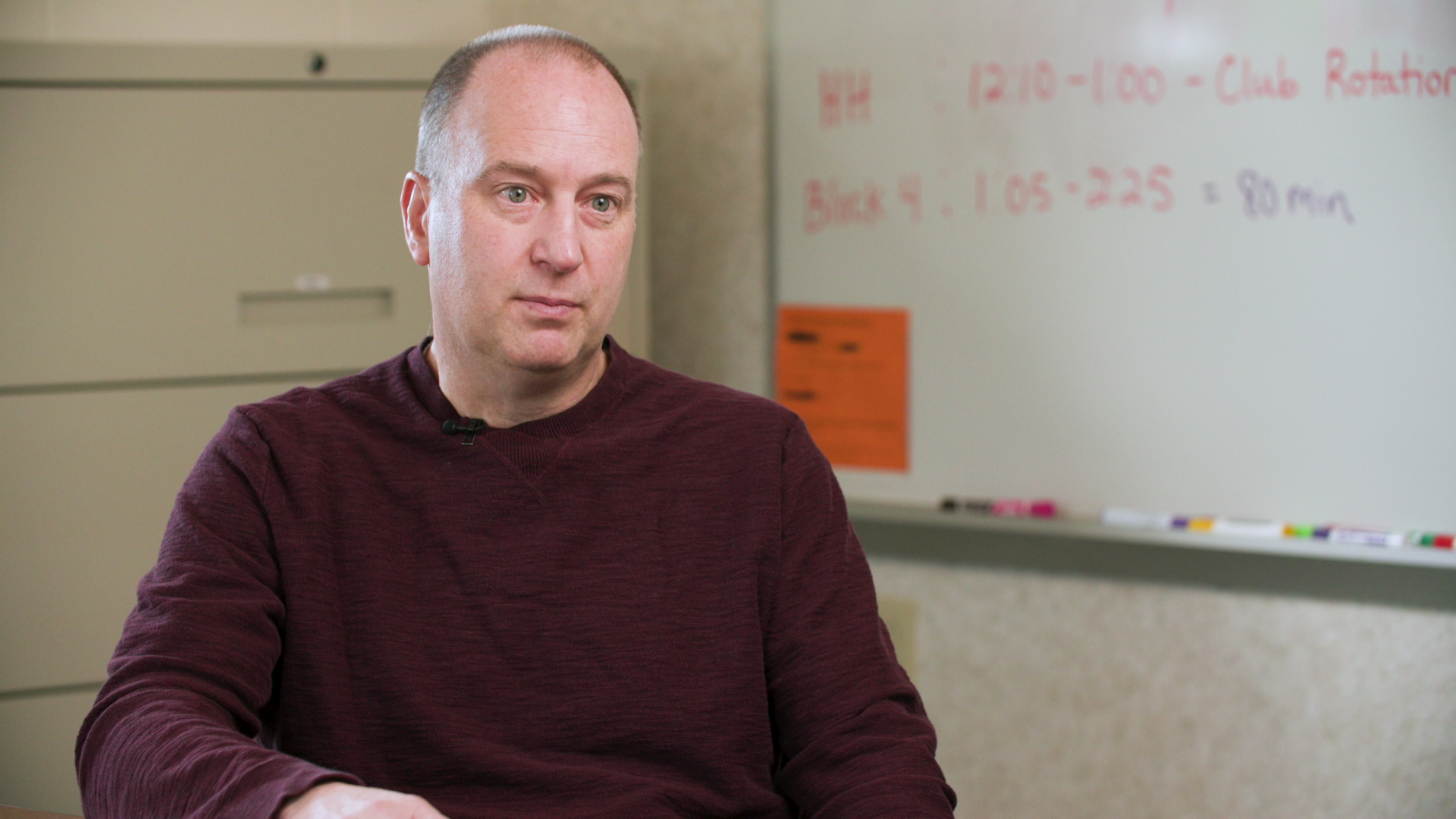

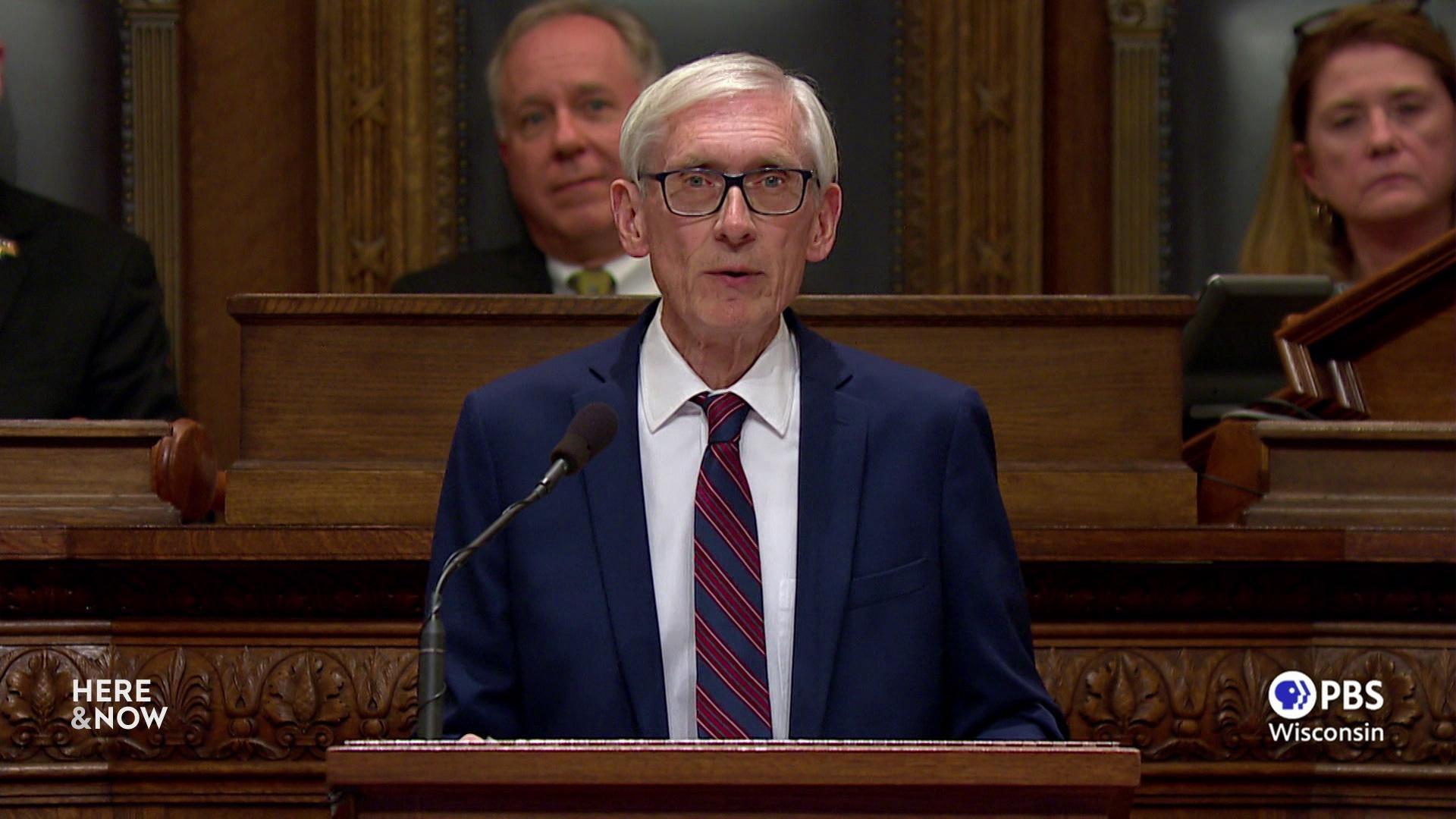

Rob Abbott is superindentendt for the School District of Fort Atkinson, which is asking voters to support an operating referendum in the spring election on April 2, 2024. It marks the third consecutive referendum sought by the district. “Districts who aren’t successful are going to be looking at significant reductions,” said Abbott. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

But how did it get to this point?

The short-term answer brings Wisconsin back to the spring of 2021, when the state had received $1.5 billion in federal COVID-19 relief aid earmarked for schools. Those funds were supposed to be used to help kids catch up from pandemic learning loss and deal with increased mental health issues, but Republicans in control of the state Legislature passed a state budget with a zero-dollar increase in per-pupil aid for students for the next two years — counting federal dollars as state funding.

“This budget, more than any other one we’ve seen in my lifetime, gives huge increases to public schools — more than they will be able to effectively spend,” said Republican Assembly Speaker Robin Vos during an Assembly floor session on June 29, 2021.

Right before the vote in a news conference, Heather DuBois Bourenane of the Wisconsin Public Education Network made this prediction: “The budget that has been put forward to our state Legislature that they will vote on one week from today in the Assembly is a promise to make existing gaps wider and existing disparities worse.”

More than two years later, DuBois Bourenane reflected on those comments: “I couldn’t have been more right about that.”

Today, she says Wisconsin has underfunded schools for 15 years, drawing a straight line from the state budget to local referendums.

“That’s an a-to-b line. That’s as straight as a line can get. The reason districts are forced to go to operating referenda right now is because they are enduring these decade-long cuts,” said DuBois Bourenane.

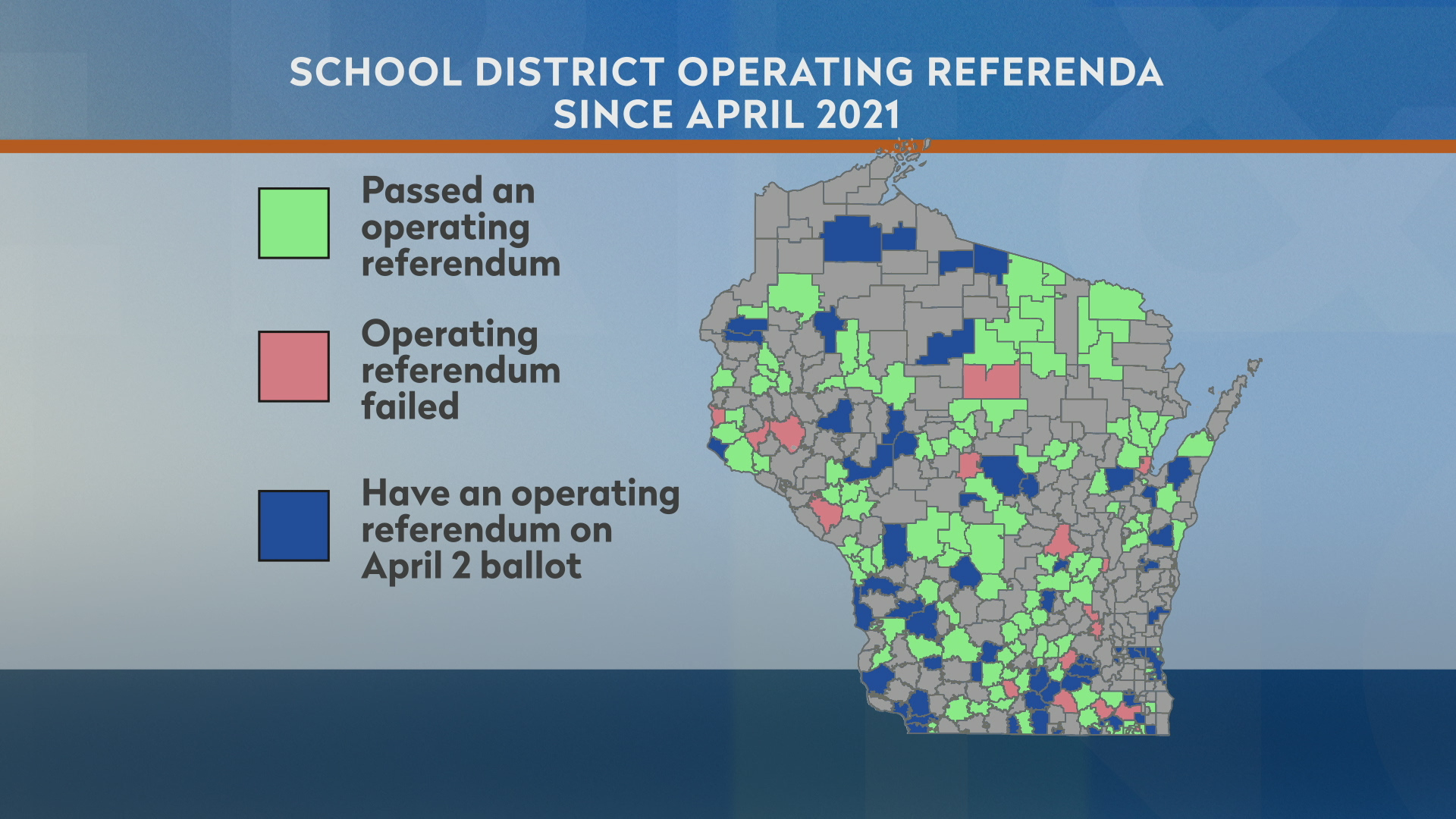

Since the start of April 2021, 152 school districts in Wisconsin have gone to the voters asking them to pass an operating referendum, some of them multiple times. There are 123 districts that have passed an operating referendum. Another 29 districts were turned down by their voters, some of them multiple times.

More than 150 school districts across Wisconsin have held operating referendums since April 21, with questions before 62 districts on the April 2, 2024 ballot. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

There are 62 districts with operating referendums on the ballot on April 2. One of those is the Richland School District.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all that many, many school districts are going to have to go to referendum just to maintain the services that they’ve been providing for our students,” said Steve Board, the district’s administrator.

He said Richland used some of their federal pandemic dollars for their intended purpose — they hired teachers to help with learning loss.

Now, they need the community to approve an operational referendum if they want to keep them.

“We tried to invest back into our students. And in doing so, we were rolling the dice a little bit because we didn’t know if those positions would continue. And obviously they wouldn’t without the support of a referendum,” Board said.

Richland is also asking for a capital referendum, to update things like an old roof and broken bathrooms.

“Our community feels that our quote-unquote new high school, which was built in 1996, is new, but it’s pushing 30 years old,” he said.

Steve Board is administrator for the Richland School District, which is seeking support from voter in and around Richland Center for both operating and capital referendums in the April 2, 2024, election. “It doesn’t surprise me at all that many, many school districts are going to have to go to referendum just to maintain the services that they’ve been providing for our students,” Board said. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

So how did Wisconsin get to this point?

While the short term points to recent state budgets, the long-term answer is older than the Richland High School.

The school levy limits were imposed by the state in the early 1990s to control property taxes. Each budget the state would increase the levy by the amount of inflation, but in the wake of the 2009 Great Recession and continuing through the Scott Walker era, the levy increases were uncoupled from inflation.

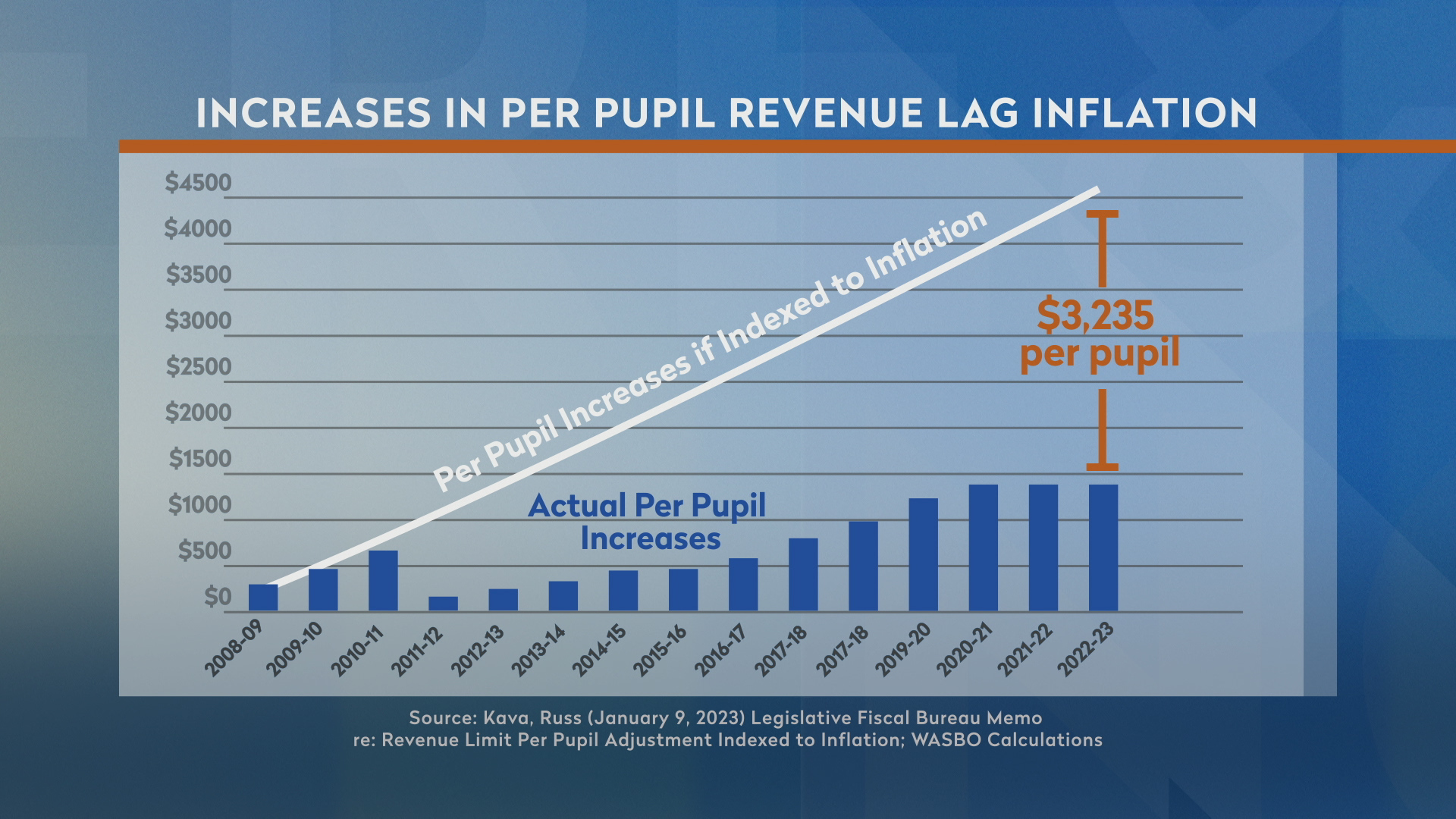

The amount of per pupil increases in state funding in Wisconsin since the 2011-23 school year has lagged behind the rate of inflation, leading to a $3,235 per pupil difference by the 2022-23 school year. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

“The shortfall now is over $3,000 per student. That’s a monumental change,” said state Rep. Scott Johnson, a Republican in the Assembly. Fort Atkinson is in his district, and he used to sit on the Fort Atkinson School Board.

“Republicans have been in charge of the biennial budgets. And it’s pretty clear that most of us Republicans want to favor school choice voucher schools, charter schools,” said Johnson.

He said too many of his colleagues in the Legislature are unfamiliar with school funding.

“Many do not understand it. It’s a convoluted, challenging system,” Johnson said.

Even fewer lawmakers have driven a school bus, as Johnson still does — and been able to see the kids that are heading to class.

“I want to give that child a good morning greeting, so that they’ve heard something positive,” he said.

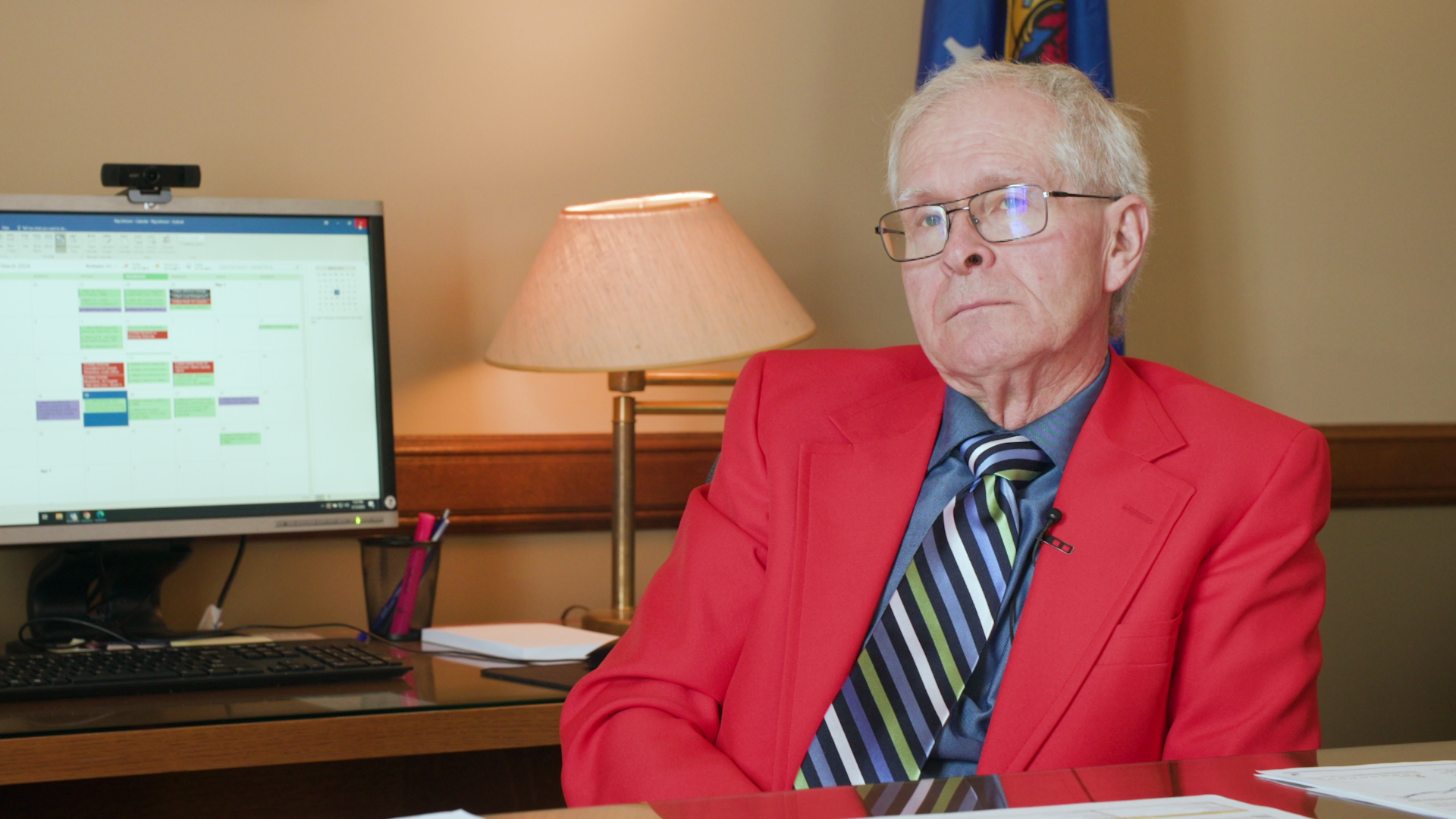

State Rep. Scott Johnson, R-Fort Atkinson, is a former school board member in the southern Wisconsin community, and continues to drive a school bus. He says many state lawmakers are unfamiliar with the school funding system. “Many do not understand it. It’s a convoluted, challenging system,” says Johnson. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Johnson said the simple truth is school districts have to pass operating referendums just to balance a budget because the state funding has not kept up.

“We’re going to balance local school budgets by referendum. And so basically every school district is facing this cliff every three or four years, depending upon how long they run their sunset referendum,” he said.

“So what happens in that situation? Local property taxpayers simply have to pay a larger share of the costs, and we’re seeing that all over the state,” said DuBois Bourenane.

In much of the state, the same voters who are deciding these referendums are the ones who elected the Republican lawmakers who underfunded the schools in the first place.

“Pointing out the gap between what voters want, what they’re voting for at the local level and what they’re getting from Republican leaders in Madison, I think is a really important missing link here that a lot of people aren’t really connecting,” DuBois Bourenane added.

But don’t expect the schools to point that out.

“We’ve worked hard to be as apolitical as possible. It’s not to our benefit to align one way or the other. But certainly the dichotomy societally is not playing to our favor,” Abbott said.

The Richland School District could not be in a more advantageous location politically — both their Republican state Rep. Tony Kurtz and Republican state Sen. Howard Marklein sit on the Joint Finance Committee, which writes the state budget.

“I also try to have conversations with Tony Kurtz and Howard Marklein, in terms of this is the reality of where school districts are at, so that they understand,” said Board.

Both Marklein and Kurtz declined to speak with PBS Wisconsin for this report.

“The folks in the statehouse are 100% to blame for that,” said DuBois Bourenane.

Heather DuBois Bourenane is the executive director of the Wisconsin Public Education Network, which advocates for public schools in the state. She points to state budget decisions promoted by Republican lawmakers as central to the ongoing trend of local school districts seeking funding through referendums. ” Local property taxpayers simply have to pay a larger share of the costs, and we’re seeing that all over the state,” said DuBois Bourenane. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Beyond school districts having to constantly return to the voters, the problem comes when you look back at the map and see in which districts referendums are failing, or where they’re not even asking for more funds.

“It’s widening the gaps across our districts, across our schools and it’s really guaranteeing that there are some kids in this state who are simply never going to see enough resources to thrive, unless we change the direction this ship is steering quickly,” DuBois Bourenane said.

“There are going to be school districts that will be doing the bare minimums across the board, and then you’re going to have the high-rent districts that will spend almost twice as much,” said Johnson. “And theoretically, we will try to tell the public that those two educational opportunities are the same. And I will suggest to you that that’s misleading.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us