What Obstacles Complicate Health Care For Rural Wisconsinites?

The same aspects of rural life that are attractive to many Wisconsinites — solitude, space, smaller communities — can often make getting the health care they need a challenge that ranges from mere inconvenience to life-threatening.

By Will Cushman

April 15, 2019

MOMS: Signs at health clinic entrance

The same aspects of rural life that are attractive to many Wisconsinites — solitude, space, smaller communities — can often make getting the health care they need a challenge that ranges from mere inconvenience to life-threatening. Long distances between medical facilities and the people they serve, as well as struggles to attract and retain healthcare professionals in rural areas, are stark manifestations of this quandary.

Medicine on Main Street, a documentary co-produced by Wisconsin Public Television and University of Wisconsin-Madison, chronicles these barriers through the stories of doctors, nurses and other health workers who practice in the state’s rural communities.

Premiering in April 2019, the documentary marks the 10-year anniversary of UW-Madison’s Wisconsin Academy for Rural Medicine, which trains and incentivizes medical students to practice in underserved rural communities around the state. The program aims to alleviate some of the most pressing rural health challenges, which the documentary investigates.

Four broad obstacles help define the difficulty of accessing rural healthcare. UW-Madison faculty and health professionals based in rural Wisconsin described these barriers in the documentary.

Recruiting and keeping rural doctors and nurses

A fundamental problem is recruiting enough physicians and nurses to work in rural communities, and then making sure they stick around.

General practitioners, who often have to be comfortable practicing a wide range of medicine, are in short supply, as well as a slew of specialists like psychiatrists and OB-GYNs.

“As a family physician here in Madison, I could focus on doing just geriatrics,” explained Byron Crouse. A former associate dean for rural and community health at UW-Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health, Crouse served as director of the Wisconsin Academy for Rural Medicine from its founding until his retirement in 2018.

“You [have] to have that full scope of practice and be comfortable with that,” Crouse said about what doctors typically need to do in rural settings, though. “And that’s a challenge that’s daunting to some people.”

Meanwhile, physician retirements and an aging population are expected to lead to a shortage of primary doctors in Wisconsin by 2035. This problem is forecast to be felt most acutely in rural communities, as detailed in a 2018 report from the Wisconsin Council on Medical Education and Workforce.

A shortage for and stigma surrounding mental health

Insurance coverage for mental health care has expanded in recent decades, especially after new federal regulations took effect in 2013. But a short supply of psychiatrists in Wisconsin means adequate care for mental health needs can remain difficult to come by even when it’s covered by insurance.

This is particularly true for Wisconsin’s small towns and farm country. An October 2018 report from the Wisconsin Policy Forum shows that 20 mostly rural counties lack a psychiatrist, and many more have only one. At the same time, sweeping economic and demographic changes are upending entire industries. Wisconsin led the nation in farm bankruptcies in 2018, and economists expect the trend to worsen in 2019.

The resulting distress can collide with cultural norms that stigmatize mental health challenges and complicate efforts to improve care and prevent mental health crises from leading to attempts at suicide.

“There is definitely still a tremendous amount of stigma where people don’t want to talk about their mental health concerns,” said Aeron Adams, a nurse practitioner specializing in mental health care who practices in southwestern Wisconsin.

“I have clients who come in and tell me that family members tell them, you know, ‘Just pick yourself up by your bootstraps and snap out of it,'” she added.

Compounding the stigma are long wait lists at the rural health clinics that offer mental health services, Adams said.

A deficit of local pharmacists

Another cornerstone of rural health — the small town pharmacy — is in shorter supply thanks to the same demographic factors affecting physicians: an aging population and increasing retirements.

“We have a lot of older male pharmacists who [own] independent pharmacies in rural areas,” said David Mott, an associate dean at the UW-Madison School of Pharmacy. “As time goes on and they get closer to retirement age, there are not pharmacists that are coming out to those environments to buy the pharmacies. Those critical access points … then close and never open again.”

A lack of in-person pharmacists can mean fewer access points for rural residents, who make up 27% of the state population. Mott noted that only 14% of new pharmacists in the state practice in rural communities.

The problem can be especially vexing given that rural pharmacists, just like rural physicians, often perform a wider range of services for patients than their urban or suburban peers.

“If you are a rural health pharmacist, you’re a jack of all trades, meaning that you’re that person that … patients are going to go to and ask any health-related question,” said Ed Portillo, an assistant professor at the UW-Madison School of Pharmacy.

The pharmacist shortage in rural Wisconsin is not a new phenomenon, and has spurred the state to attempt to expand care through telemedicine.

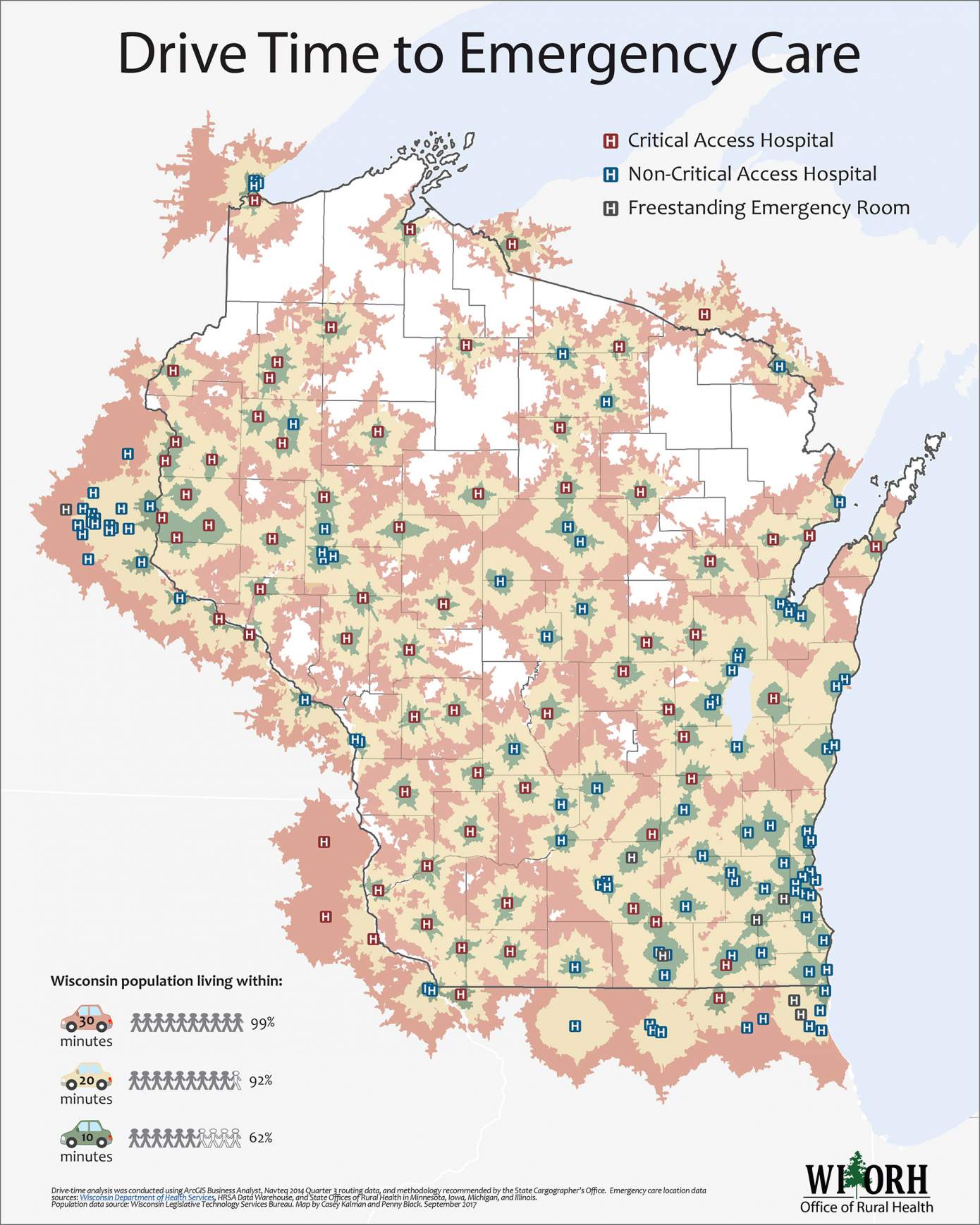

The tyranny of long distances

Wisconsinites who live in rural areas generally must drive (or be driven) farther to receive medical care. And as communities cope with a shortage of physicians, nurses, pharmacists and other medical specialists, this deficit means rural residents often have to drive even farther.

Many rural communities, including wide swaths of Wisconsin’s northern reaches and pockets elsewhere, are designated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as “Frontier and Remote,” which is defined by distance from important goods and services, including health care. In addition to scheduled health services, most residents in these areas lack nearby emergency facilities, which can have deadly consequences when they need immediate care.

Non-emergency medicine is less scarce than hospital emergency rooms, but rural patients often still must travel long distances to receive basic care. The same is true for many health care professionals, who often commute between clinics in multiple communities.

For instance, Aeron Adams, the mental health nurse practitioner, commutes 80 minutes two days a week between her office in Dodgeville and a clinic in Lancaster.

“I’ve had patients routinely drive a half hour, 45 minutes to get to an appointment with me,” Adams said.

The drives are even longer in other parts of the state, according to Gina Bryan. A professor at the UW-Madison School of Nursing, Brown coordinates the psychiatric-mental health certificate program.

“We’re seeing [new students] come from the parts of the state that don’t have psychiatric providers … within a two-to-three hour drive,” Bryan said.

Long drives are the reality for patients in need of other kinds of specialty care too: 20 of Wisconsin’s counties do not have a single practicing OB-GYN, meaning expecting mothers in many rural communities also have to drive long distances for care.

Rural residents in Wisconsin face additional health challenges, including limited access to dental care and treatment for addiction to opioids and other substances, and difficulties in recruiting volunteers to provide emergency services. And while many of the health problems common in the countryside also plague the state’s cities, the sheer breadth of distance between provider and patient adds to rural areas’ health care burden.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us