What A 1977 Inferno In The North Woods Left In Its Wake

The drought-parched spring of 1977 was a particularly dangerous season of wildfire, with a trio of big burns in west-central Wisconsin and the Five Mile Tower Fire in the state's northwest corner.

April 24, 2019

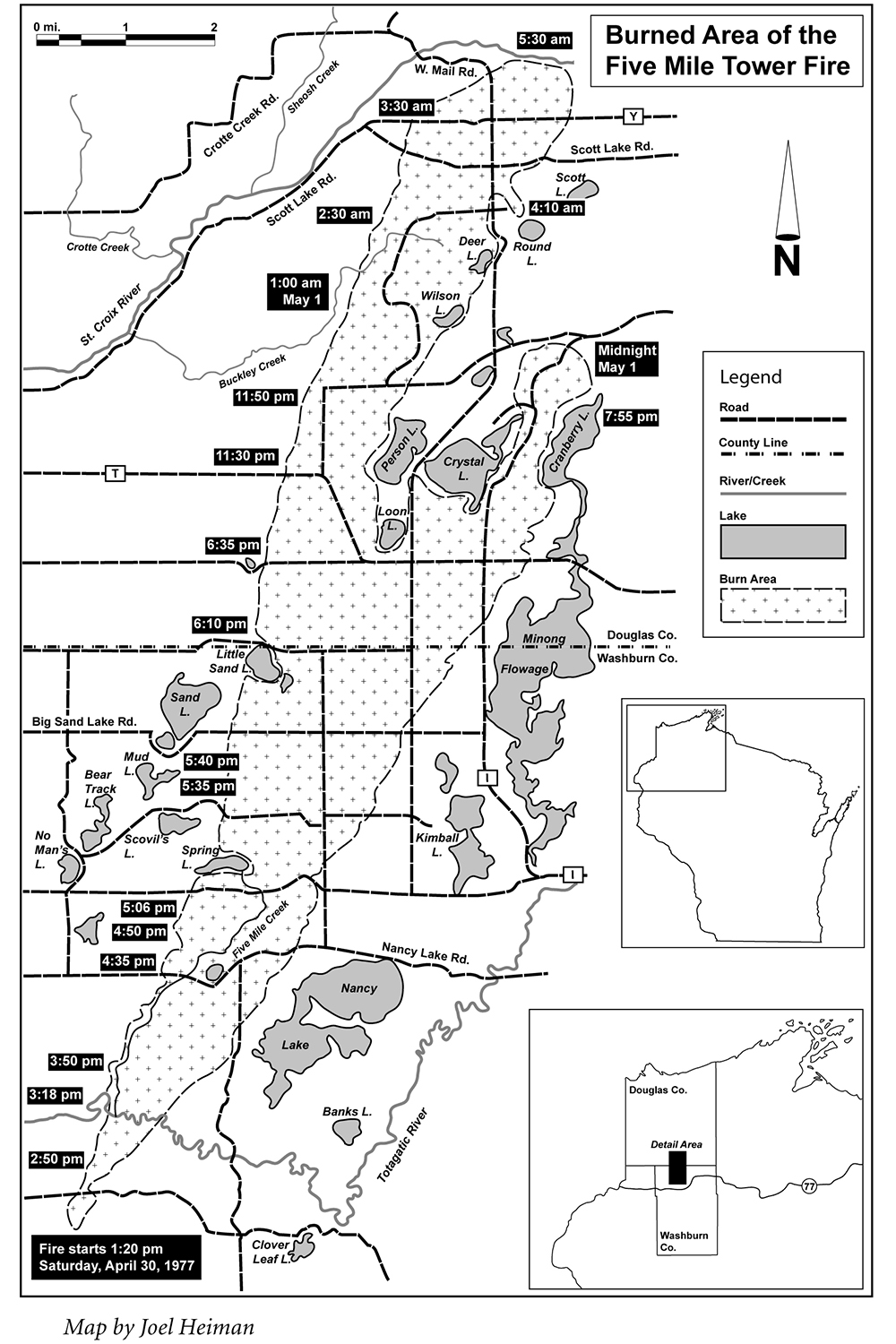

Five Mile Tower Fire crossing Highway T

Wildfire is a familiar element of ecological destruction and renewal in the expanses of field and forest, and an ever-present risk to the people who make their lives and livelihoods in these landscapes. Since the state’s founding, Wisconsin has experienced countless smaller fires and a handful of major blazes, leading with the 1871 inferno in Peshtigo that was the deadliest in United States history. The drought-parched spring of 1977 was particularly dangerous, fueling a trio of big burns in west-central Wisconsin and another in the state’s northwest corner known as the Five Mile Tower Fire. Straddling Washburn and Douglas counties, this forest fire started on the afternoon of April 30 and continued into the early hours of the following morning. The flames incinerated over 13,000 acres of pine forest and destroying 63 buildings, and there has not been a larger wildfire in the state since. Bill Matthias was a school superintendent in Minong, and was among more than 1,600 people from throughout the region who mobilized to contain and extinguish the blaze. These volunteers included Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources rangers and wardens, pilots and bulldozer operators, local firefighters, even high school students and their teachers, along with community members that fed and sheltered them. How this wildfire started, spread and was stopped is detailed in the book Monster Fire at Minong: Wisconsin’s Five Mile Tower Fire of 1977, written by Bill Matthias and published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press. An excerpt from the book describes the aftermath of the fire, its effects on the burned area, surrounding forest and communities, and how it informed wildfire management practices in the state and around the nation.

One match sparked Wisconsin’s largest single-source forest fire in 50 years.

The Five Mile Tower Fire raged without stopping for 17 hours. It was a crown fire, long and narrow: 15 miles long and 3 miles wide at the widest. For people living in this region, it seemed as though their whole world was ablaze.

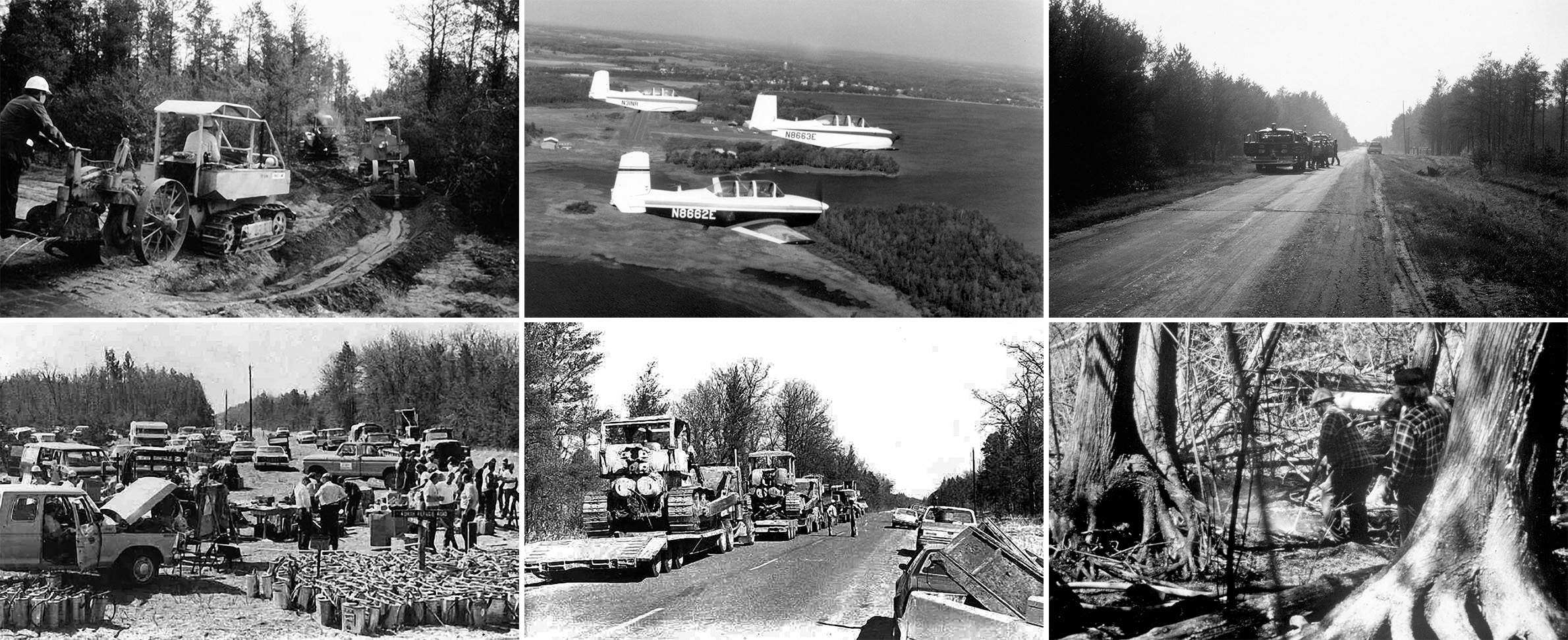

During the afternoon and evening hours of April 30, 1977, more than 400 people were evacuated by conservation wardens, county sheriff deputies and the public-address speakers mounted on the bottom of DNR airplanes. Forty roads were blocked to keep onlookers safe from the flames and potential looters away from the abandoned cabins and homes.

As the fire advanced, steadily chewing up 1 mile every 41 minutes, nine volunteer fire departments came to assist in working the fire lines along the edges. Their knowledge, speed, and bravery also saved a total of 323 buildings. Sixty-three structures were lost, including some people’s only homes.

Helping the 14 DNR dozer-plow units were 31 private bulldozers. The National Guard provided six huge dozers, operated by the Wisconsin National Guard 724th Engineer Battalion.

In total, 43 miles of drivable 20-foot-wide fire lines were plowed around the fire perimeter. This is the equivalent of the highway department cutting a rough road from Gordon to Superior, or from Madison to Janesville — through the middle of a forest, over swamps, around lakes, and over rivers — in less than one day!

The first eight miles of the fire burned mostly Mosinee Paper Mills forest lands, and the final seven miles blackened primarily Douglas County forest lands. Some private plantations were lost as well.

In all, 22 square miles burned.

The tragedy and the sheer immensity of the fire galvanized the entire regional community of Spooner, Minong, Wascott, Gordon and Solon Springs. About 1,600 people fought on the fire, but that number doesn’t include all of the police officers and ambulance emergency medical service personnel on the scene in standby mode, the hundreds of women and men making food, or all of the men and women driving water tanker trucks of all shapes and sizes. It doesn’t cover individuals delivering diesel fuel or gasoline to the fire zone or the many private dozer operators and National Guard dozer drivers.

In the end, probably well more than 2,000 people worked to put out this menace over a two-week period.

Most amazing is the fact that no one was killed, no one was seriously injured, and there were no reported hospitalizations as so many people worked in such dangerous conditions. Many came close to danger, and some even felt the flames up close, but everyone went home to their families, school friends, and relatives.

John Schultz, the landowner who unwittingly unleashed an inferno when he lit a match to start a campfire, would be charged by Washburn County district attorney Patrick H. Stiehm with a misdemeanor violation of statute 26.14(6) for starting a fire and allowing it to escape. Schultz stood trial in March 1978 in Washburn County Court before Judge Warren Winton.

Other than a brief newspaper account by the Spooner Advocate and the memories of those in attendance, there are no records of Schultz’s trial; according to the Washburn County district attorney’s office and the Washburn County clerk of courts, records of misdemeanor trials are kept for only a short period.

At the time of the Five Mile Tower Fire there had been no burning ban in effect, and the jury felt that Schultz had taken reasonable precautions in preparing the fire pit and trying to keep the cooking fire small. On March 31, 1978, the jury found Schultz not guilty.

When the jury’s decision was announced, the prosecuting district attorney Stiehm stepped over and gave Schultz a congratulatory hug. Several of the DNR rangers in attendance who had worked hundreds of hours on the fire quite naturally cringed.

At the time of the Five Mile Tower Fire, Mosinee Paper Industrial Forests (now Wausau Paper) owned 75,000 acres in northwest Wisconsin. As the fire raced through Washburn County during the first five hours, most of the land destroyed was owned by Mosinee. In all, the company lost 4,426 acres. It was a major blow, and it would be another 30 to 40 years before any pulp wood could be taken from the devastated 7 square miles.

Terry Michal, Mosinee Paper’s lead forester, and Steve Coffin, second in command, were called to fire headquarters with their 10-man logging crew to help with the fire and offer assistance in intelligence and mapping. The Mosinee men were assigned to the hot east flank of the fire after it had jumped the Totagatic River; there they had hooked up with Bobby Hoyt’s DNR dozer and plow from Gordon and worked on the dangerous right-hand divisions for many hours. These were experienced woodsmen and were given the toughest assignments.

At 3 a.m. they were transferred all the way to the St. Croix River to help with the firefighting in the northeast sectors. After more than 24 hours on the fire, the Mosinee crew was released.

The Mosinee employees’ fear that their losses would be catastrophic were confirmed by later timber cruising and airplane observation mappings. A single landowner lost 32% of the total acreage burned in the Five Mile Fire. That was the Mosinee Paper Industrial Forest.

In the fire’s aftermath, what was the company to do with all of the burned timber?

The paper mill couldn’t use the charred trees, because pieces of black carbon embedded in the standing dead timber would show up in the pulp and later in paper products. The company tried a novel approach and sold the logs by the millions to chipping operations.

The entire tree — trunk, branches, cones, and all — went into the hopper for pulverizing. The wood chips containing black ash particles and blackened bark were sold to turkey farmers for turkey bedding. The company got rid of the burned wood, and the turkey producers obtained nice pine bedding with charcoal pieces, useful for smothering smells, much as it does when utilized in filters for air masks and fish tanks.

Still, the impact of the fire losses gave Mosinee Paper a renewed awareness of its responsibilities in fire protection. The company purchased a new dozer and attached a fire plow to it and also bought slip-on tanks and hoses for the pickup trucks.

In 1980, three years after the Five Mile Tower Fire, the Oak Lake Fire started just a few miles down the road. As it burned south, pushed by a hot north wind, it destroyed 11,418 acres. It was then that the foresters got worried. Pine covers northwest Wisconsin in huge blocks from Grantsburg northeast all the way to Iron River. The fire destruction and inability to stop a crown fire in the pines led the foresters to consider massive firebreaks as a part of forestry thinning.

Mosinee Paper, along with several county forestry departments, clear-cut quarter-mile-wide swaths of timber for pulp and sawed wood production to create a firebreak that would have a chance of containing a large fire. These corridors were 6 or 7 miles long. Several years later, when the cleared strips started growing young trees again, the foresters would go north or south and clear another long path.

Russell Hill owned almost two hundred acres along the St. Croix River. At the time of the Five Mile Tower Fire, the U.S. Park Service had been trying to purchase Hill’s property under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act with plans to remove all of his buildings and return the land to pristine wilderness.

Hill had built many buildings — garages, painting studios, storage sheds, and, in the midst of the forest, an authentic western village, complete with Chinese laundry, Wells Fargo station, barber shop, sheriff’s office, general store and blacksmith shop, all purchased out West, hauled to Gordon and reassembled. The buildings contained priceless antiques and equipment. Hill had steadfastly refused to sell.

As the fire approached his estate, Russell Hill was seen in his pickup truck several miles away on West Mail Road. Gordon Fire Department members yelled at Hill to get back home; his place was threatened and his wife was there, in danger.

When the fire raced through his acreage and burned many of his buildings, Hill was devastated. Of all his buildings, only his home was saved — by heroic effort. He thanked the firemen and the DNR.

After a fire, regeneration and renewal come slowly. Every year on the anniversary of the Five Mile Tower Fire, Minong ranger Bill Scott would drive to the same intersection of Highway T and the sand road, the epicenter of the fire. There he witnessed the changes.

The first year there was some greening of the ground plants, and many of the standing black trees were gone, harvested for grinding and sold for turkey bedding. The second year he saw many kinds of brushy plants and larger blueberry bushes full of bunches of wild blueberries. By the third year, the resilient jack pine seedlings were sprouting up by the thousands.

By 2010, you would not know a fire had occurred there. Nothing was left of the fire’s devastation except for a blackened stump here and there. The dead oaks regenerated from their roots into new trees, destroyed red pine plantations were cut and replanted, and the fire-loving jack pines that burned regenerated because of their tough cones that opened and scattered seeds by the thousands. In 2000, the Fire Hill Golf Course was carved out of the wooded acreage on Hill Road near what was the north end of the blaze.

The Five Mile Tower Fire took many miles of fire lines and many thousands of gallons of water to extinguish. However, what came after could only be described as a watershed — or perhaps waterfall — of reviews and changes.

Rangers from throughout the state reported that the Five Mile Tower Fire was the agent of change. It sparked extensive sessions of critical analysis and soul-searching. Experts interviewed for this book agree that the fire led to hundreds of changes that can be seen to this day in firefighting philosophy, management, communications, and equipment.

In many human endeavors, sometimes it takes a tragedy or a series of unpleasant events to usher in a new beginning, a better system, or an updated organization with modernized goals and objectives.

There were 11,744 forest fires fought by the DNR in combination with rural volunteer fire departments in Wisconsin in 1976 and 1977 — an average of 16 fires each day. These fires burned a total of 119,288 acres — 186 square miles of Wisconsin woodlands reduced to blackened stumps.

These two years of losses made everyone from the governor on down take notice. In every region of the state, forestry leaders sat down during the late summer of 1977, studied the fires of the previous two years, and listed their recommendations for improvement.

While changes in firefighting obviously were needed, management of the Five Mile Tower Fire itself was handled so well that it became an example of excellence at the National Advanced Resource Training Center in Arizona. For several years, it was used as a training exercise in the Advanced Forest Fire Behavior Officer course.

Wisconsin’s training and ability surprised fire managers all over the country, especially in the West. The rate of spread of the Five Mile Tower Fire of one mile every 35 to 40 minutes was faster than even the massive fires in the western wilderness.

Fire experts from California, Alaska, Idaho and other states studied the Wisconsin blaze. They determined that, given the fuel types and weather conditions, this fire could have been many times larger. They were impressed that it was contained in such a relatively small area. They also found that the firefighting effort was well organized and the cost of suppression was just a fraction of their estimates.

Still, there was room for improvement.

This item was excerpted from Monster Fire at Minong: Wisconsin’s Five Mile Tower Fire of 1977, published by Wisconsin Historical Society Press.

Author Bill Matthias became superintendent of Northwood School District in Minong in 1975. While he was superintendent, he launched the teenage firefighting crews at Northwood High School and battled the Five Mile Tower Fire for 50 hours. He is a charter member of the Wascott Volunteer Fire Department.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us