Understanding The 2015 Wisconsin Avian Flu Epidemic: The U.S. Outbreak

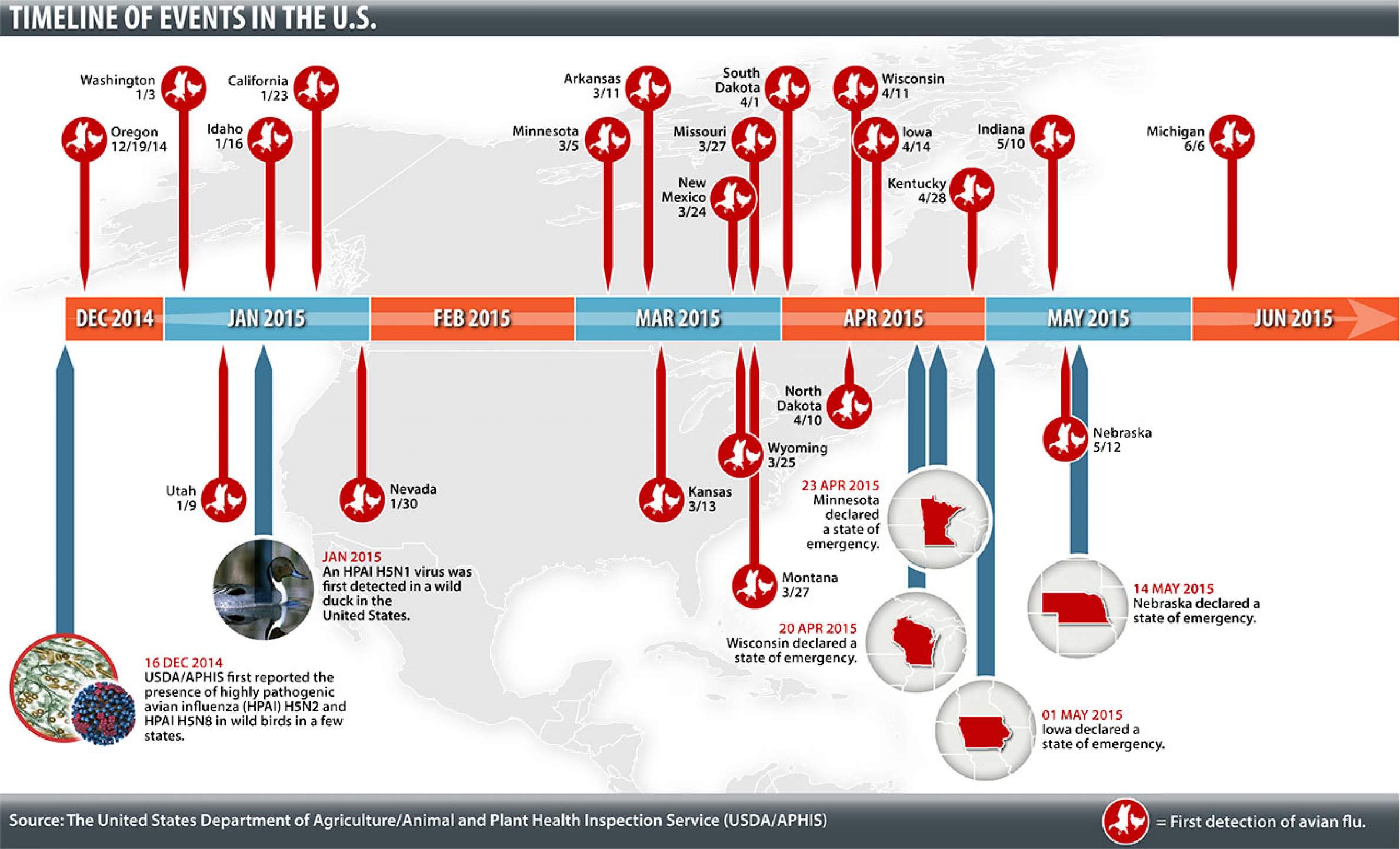

The 2015 avian influenza epidemic was the largest in U.S. history, affecting more than 48 million domestic poultry birds in 15 states between December 2014 and June 2015, according to the U.S. Department ofAgriculture's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

May 19, 2016

US avian flu outbreak

What was the 2015 avian influenza epidemic in the U.S.?

The 2015 avian influenza epidemic was the largest in U.S. history, affecting more than 48 million domestic poultry birds in 15 states between December 2014 and June 2015, according to the U.S. Department ofAgriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

There have been three earlier serious avian flu epidemics in the U.S. Previously, the worst on record was in 1983, when 17 million affected birds had to be killed — or “depopulated,” to use the regulatory and industry parlance. By comparison, outbreaks in 1924 and 2004 were tightly contained and quickly resolved.

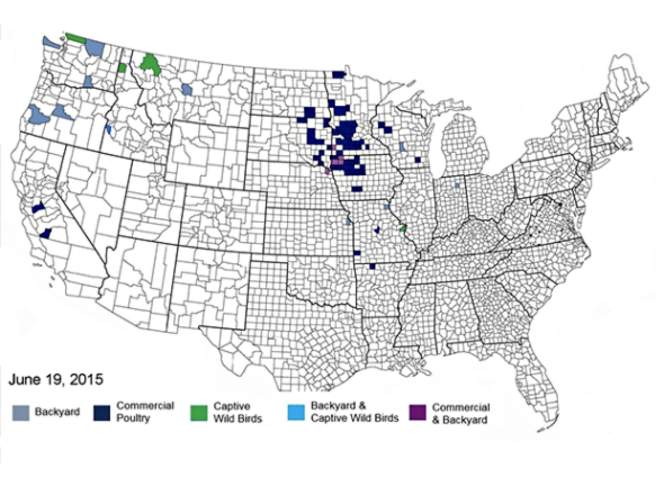

The first avian flu detection in this latest epidemic was in December 2014, in a small flock of guinea fowl and chickens in Oregon. Cases were also identified in Washington state and California, as far south as Arkansas and as far east as Indiana. The last reported detection in this outbreak was on June 17 in north-central Iowa, among a flock of 1 million egg-laying chickens.

Iowa suffered by far the worst losses of any state, depopulating 34 million birds, followed by Minnesota at more than 9 million and Nebraska at about 5 million. The flu also struck poultry in Idaho, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota.

A summer 2015 report issued by the U.S. Department of Agriculture didn’t name any one specific culprit for the virus’ introduction and spread, and agriculture officials are still working toward a better understanding of the epidemiology of this outbreak. But it’s generally believed that wild birds pass the virus to farm animals and that flaws in biosecurity practices helped it spread from farm to farm. Wild birds migrate through the U.S. along four different regional paths, or “flyways,” which is one reason that the virus cannot necessarily be said to have spread along a clearly identifiable geographic path. It could well be that wild birds along the Pacific Flyway touched off the H5N2 infections on the West Coast, and that birds using the Mississippi Flyway were responsible for bringing it to the Midwest.

An economist told National Geographic in July that the outbreak had caused $3.3 billion in economic losses nationwide. Looking ahead, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack has told Congress that the USDA is bracing for a potential return of avian flu in the autumn, as dropping temperatures and southward-migrating birds create more hospitable conditions for the virus to spread. Speaking at a conference in August, Vilsack also admitted that “the best biosecurity job may not be good enough.”

An interactive map is available here.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us