'They die so quickly': Fentanyl is killing over 1,000 people in Wisconsin each year

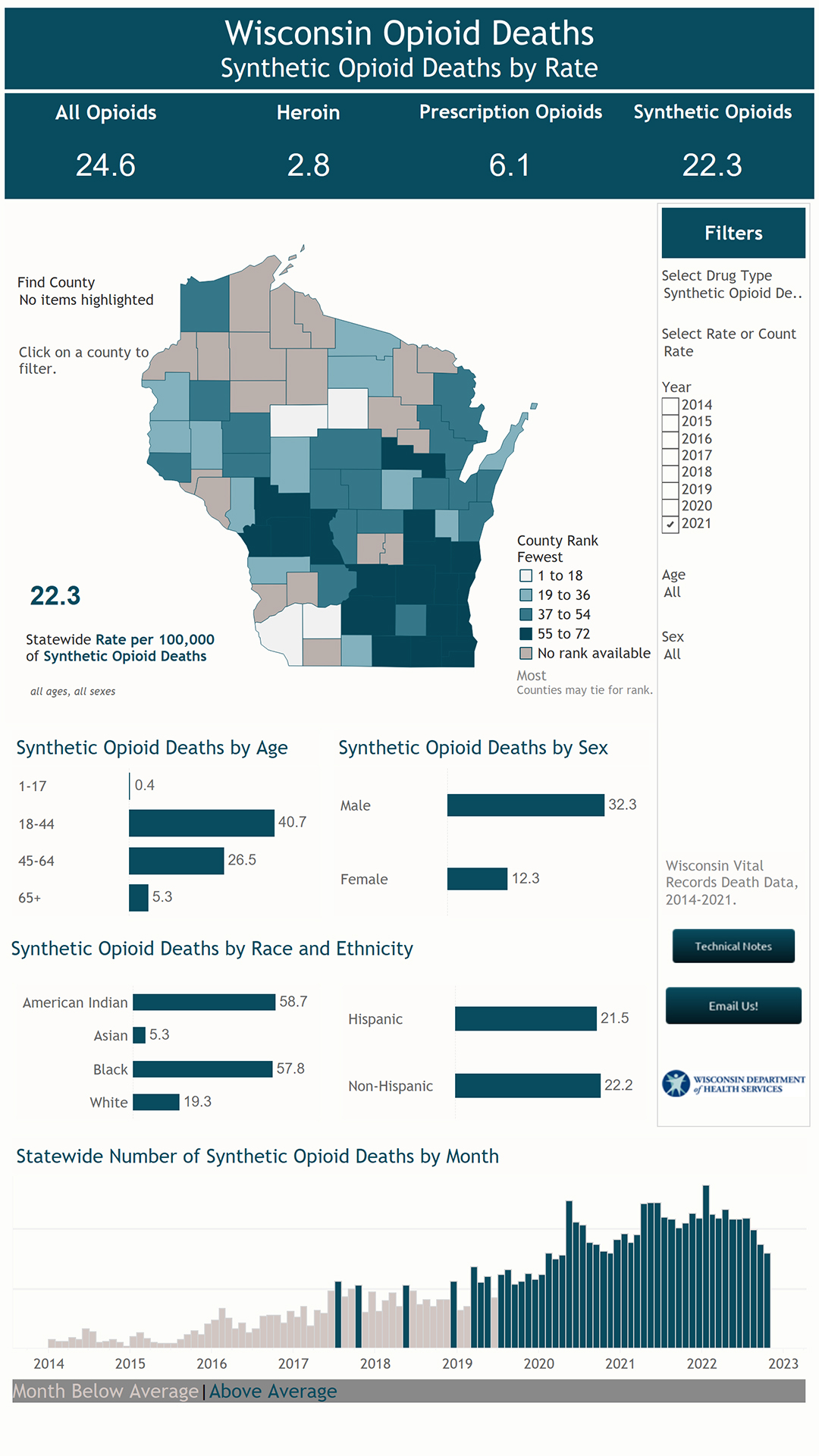

Wisconsin's synthetic opioid crisis worsened in recent years, with provisional state data showing there were 1,358 opioid overdose or poisoning deaths in 2022, a figure more than 60% higher than five years earlier.

Wisconsin Watch

July 12, 2023

Erin and Rick Rachwal and their son Caden mourn at the funeral of their son and brother, Logan Rachwal. The family launched a foundation to warn of the dangers of opioids after Logan overdosed on a pain pill laced with fentanyl on Feb. 14, 2021. (Credit: Courtesy of the Rachwal family)

This article was first published by Wisconsin Watch.

Logan Rachwal was 19 years old when he lost his life to fentanyl in 2021.

The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee student, like many others impacted by the drug, did not know he was taking fentanyl. According to his parents, Rachwal took a fentanyl-laced pain medication and died within minutes.

Fentanyl doesn’t discriminate, said Rick and Erin Rachwal, Logan’s parents, “It’s going to affect everybody.”

Just over a year after his death, the Rachwal family started the Love, Logan Foundation, which aims to educate people about the dangers of fentanyl and reduce the stigma surrounding fentanyl and substance use.

Fentanyl, which has been adulterated into other street drugs since 1979, is roughly 50 times more potent and stronger than heroin and has dramatically increased overdoses and poisonings.

In 2021, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services found synthetic opioids, particularly fentanyl, caused 91% of opioid deaths. In May, the department announced $18 million in new funding for drug abuse treatment and prevention, including fentanyl.

Wisconsin’s synthetic opioid crisis worsened in recent years. Provisional data from DHS shows there were 1,358 opioid overdose or poisoning deaths in 2022, a slight decrease from 2021 but still a 62% increase from five years earlier.

(Credit: Courtesy of the Wisconsin Department of Health Services)

When illegally selling drugs, individuals can mix fentanyl into their products, allowing them to sell smaller quantities with the effects feeling strong or stronger for the users. Those same dealers can cut costs by quickly adding bulking agents to fentanyl, making it much cheaper to buy than heroin — one reason for the dramatic increase in synthetic opioid deaths in recent years.

The Rachwal family noticed how readily available fentanyl has become.

“It’s not like it was 30 years ago. It’s just not. These kids aren’t buying needles and powder and injecting their arms at 17, 18, and 19 years old. They’re taking pills to make themselves feel better,” said Erin Rachwal. “Which they can get all over. A lot of kids aren’t even getting to a point where they have an addiction yet because they die so quickly. Logan was young.”

Addiction started with oxycodone

Logan Rachwal was 14 years old when his family first noticed his addictive tendencies. Logan had knee surgery and was prescribed oxycodone to deal with the pain.

“About three days post-surgery, we noticed he was enjoying being high. … He was sitting in a recliner, and Rick and I looked at each other, and we just were like, ‘Holy cow, we need to get this medicine away from him,'” said Erin Rachwal.

Erin and Rick Rachwal described Logan as a sweet-hearted, somewhat anxious child who endured adversity at a young age. They emphasized that he became very intense when passionate about something and tried to learn as much as possible. To help with his anxieties, Erin and Rick felt that he naturally wanted to teach himself about self-medication.

This is a photo of Logan Rachwal while he was a senior in high school. Rachwal overdosed on fentanyl in his dorm room the following year at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He is among more than 1,000 Wisconsinites who died of a synthetic opioid overdose in 2021. (Credit: Courtesy of the Rachwal family)

Logan’s parents tried all sorts of treatment strategies with him, from switching schools to different therapists and more.

“There’s no perfect family, but… I think to this day we still sort of look at each other like ‘How could this have happened?'” said Erin Rachwal. “We were good parents, you know, I feel like we were very involved with our kids… I now know the answer to how this could happen because it’s happening to so many families and so many people.”

Awareness could have saved life

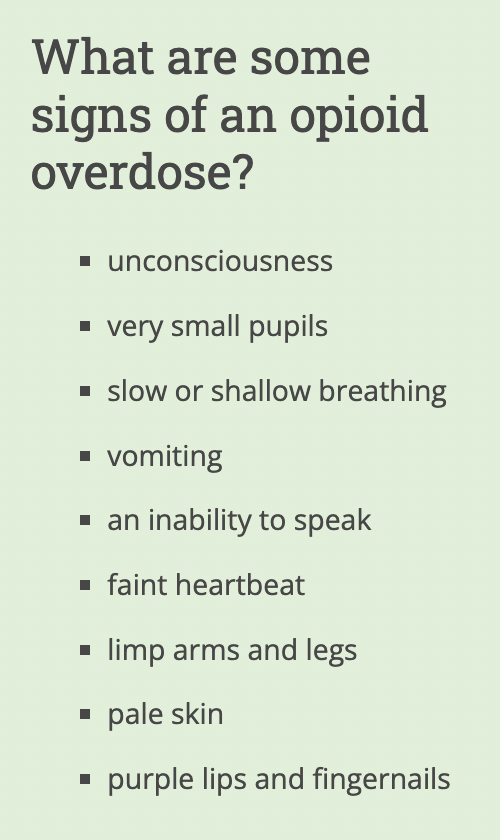

Logan was on the phone with his girlfriend when he died. His parents pointed out that if his girlfriend, and others, knew the signs of a body’s response to an opioid, Logan could have been saved.

“Two years ago… even for us… the awareness was not there. So yes… the girlfriend didn’t know, Logan didn’t know, we didn’t know what to do… the schools didn’t know” said Erin Rachwal. “So all of this lack of knowledge got us to a point where we decided to start a foundation.”

Erin and Rick started the Love, Logan Foundation in the summer of 2022 after attending a Drug Enforcement Administration summit in Washington, D.C. Although the foundation is still young, it’s doing as much as possible to spread awareness about fentanyl’s dangers. The parents mainly run the foundation, alongside a board of six people who help make decisions.

Erin and Rick Rachwal formed the Love, Logan Foundation after their son, Logan Rachwal, died of a fentanyl overdose in 2021. This billboard along Interstate 94 in eastern Wisconsin is one of the foundation’s projects. (Credit: Courtesy of the Rachwal family)

The Rachwals have spoken at several Wisconsin schools. They’ve erected a billboard on I-94 and plan to host a golf fundraiser. Both parents emphasized the importance of raising awareness among Wisconsin’s youth.

“The largest group I’ve spoken to so far was about 120 kids in February.” Erin said. “That was such an awesome feeling when I left there. I had left, and I was just on Cloud 9 because … you just felt like you were actually impacting the people you need to impact.”

‘Slow-moving thing’ to change drug policy

Erin Rachwal has met with the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction and DHS several times since starting the foundation. She has tried to get legislation passed, but she described it as “a real slow-moving thing.”

Although both Democrats and Republicans tend to agree that there is a national crisis regarding fentanyl, they differ on how to respond to it.

Republicans see the fentanyl crisis as a border issue, often referring to evidence that most of the supply of fentanyl and related synthetic opioids is made and brought in from Mexico. In February, 21 Republican state attorneys general wrote a letter to President Joe Biden and Secretary of State Antony Blinken calling on Biden to designate Mexican drug cartels as foreign terrorist organizations. In September 2022, a bipartisan coalition of 18 attorneys general pushed for Biden to declare fentanyl a “weapon of mass destruction.”

Democrats view the fentanyl epidemic as a public health crisis and tend to blame pharmaceutical companies and the roles of prescription drugs. Researchers Daniel C. Stokes and Anish K. Agarwal at the University of Pennsylvania describe the Democrats’ response to fentanyl as focused on funding and more treatment.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse lists these signs that a person may be suffering an overdose of fentanyl or another opioid. (Credit: Courtesy of the National Institute on Drug Abuse)

At the federal level, Rep. Scott Fitzgerald and Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin, along with three of their Republican Senate colleagues, introduced the Stopping Overdoses of Fentanyl Analogues (SOFA) Act in March. The bill was first introduced by Johnson in 2017.

“Fentanyl is more potent than morphine and heroin and the leading cause of overdose deaths in 2021,” said a statement attributed to Fitzgerald, who passed similar legislation while in the Wisconsin state Senate. “Too many families are losing loved ones to drug overdoses fueled by fentanyl.”

The bill would classify synthetic drugs similar to fentanyl as Schedule I, making it easier to prosecute individuals who make and traffic the drugs. Schedule I drugs are those with “no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse,” including heroin and LSD.

Johnson said in a press release that the bill aims at “preventing new fentanyl-related substances from entering our communities.”

Rescue boxes deployed

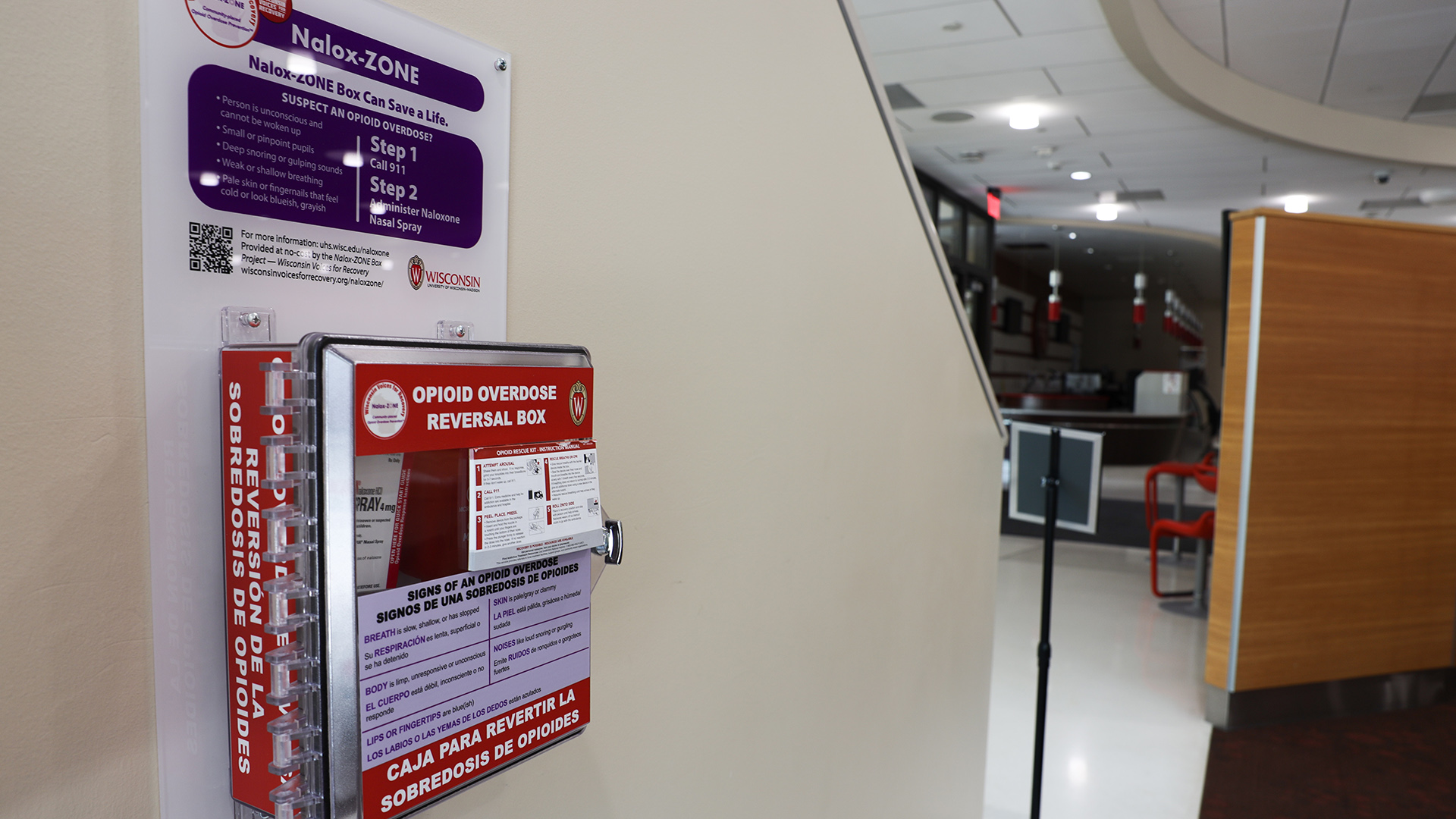

At least six University of Wisconsin schools, including UW-Madison and UW-Oshkosh, have installed overdose or poisoning rescue boxes in buildings on their campuses.

Wisconsin Voices for Recovery, an advocacy group that raises awareness and helps individuals struggling with substance abuse, has placed the boxes on Wisconsin campuses. The group calls its project Nalox-ZONE.

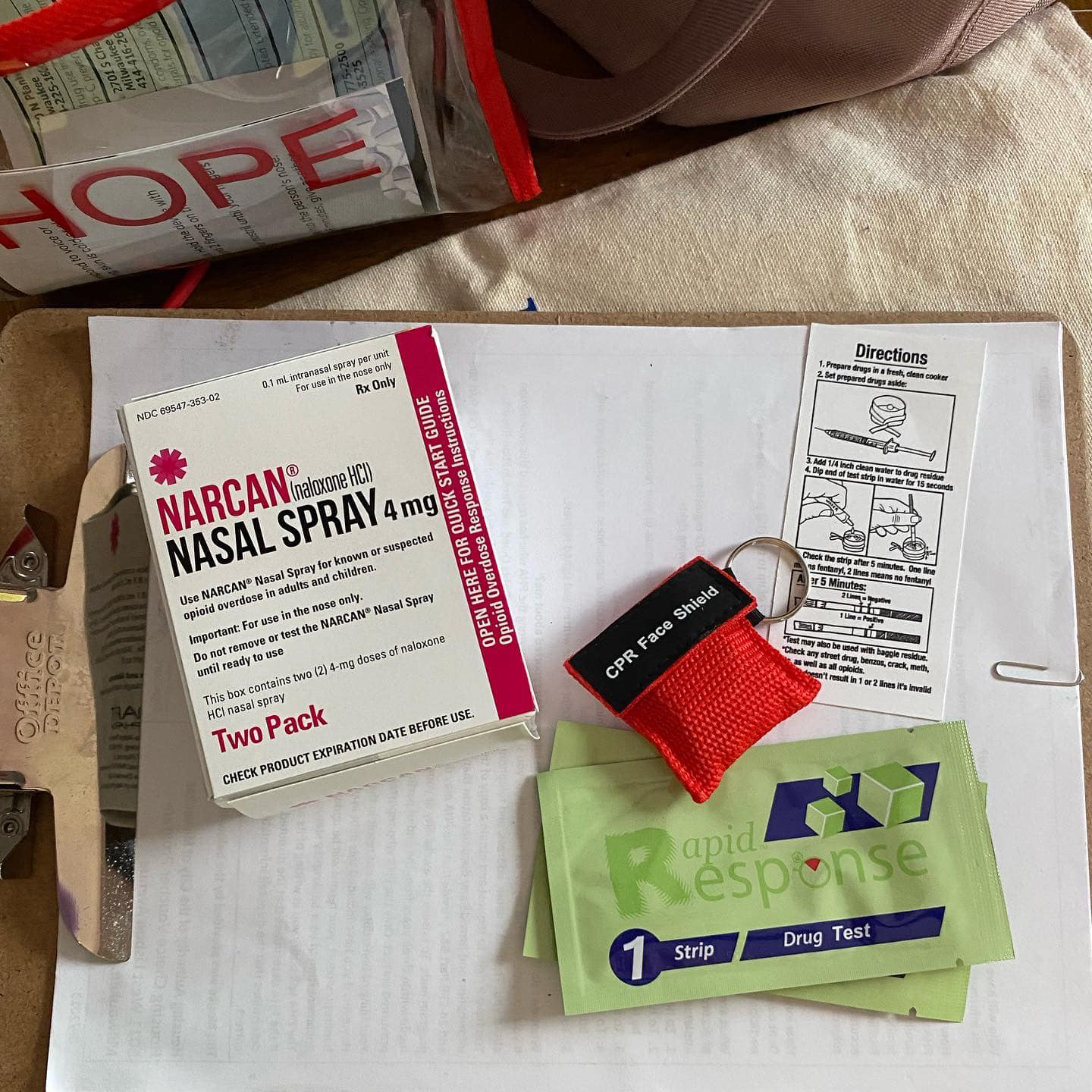

These kits, funded by the DHS, contain a potentially life-saving medicine, Naloxone Nasal Spray, which helps reverse the effects of an overdose or poisoning from heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone or morphine. The boxes contain two doses of the nasal spray and instructions on how to use it.

A box containing free naloxone, also commonly known by the brand name Narcan, hangs in Gordon Dining and Event Center on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus. The box was provided through the Nalox-ZONE Program which aims to increase naloxone availability throughout Wisconsin to reduce opioid overdose deaths. (Credit: Drake White-Bergey / Wisconsin Watch)

University Health Services and University Housing have been educating students on the dangers of fentanyl-laced drugs and poisonings. Staff at university housing also have received training on administering the nasal spray. University Health Services plans to expand the program to other campus locations in the future.

Erin Rachwal spoke about the importance of providing kits on campus and educating students on how to use them — but also having people who can tell personal stories about the dangers of fentanyl.

“To me it’s like the Narcan (a brand name for naloxone) goes hand in hand with a presentation, an understanding and education,” she said. “If you do one without the other, you’re not being effective.”

More naloxone, less stigma

Although the boxes can help with emergencies, data that Wisconsin Voices for Recovery has collected shows many people are grabbing the boxes — just in case.

“What we really want is the Narcan to get out there in the community,” said Cindy Burzinski, director of Wisconsin Voices of Recovery. “We want people in Wisconsin to be safe, and so the fact that a lot of people are taking the Narcan that’s not for an emergency, is really encouraging.”

“People are becoming more comfortable accessing the boxes,” Burzinski added, “which is, in turn, maybe reducing the stigma around having Narcan on hand.”

The contents of a Milwaukee Overdose Response Initiative “Hope Kit” are shown, including Narcan nasal spray to temporarily reverse the effect of opioids, CPR face shields and fentanyl testing strips. (Credit: Courtesy of MKE Overdose Prevention)

Wisconsin Voices for Recovery seeks to combat this stigma that discourages many people from seeking help. The group interviews people in recovery about their experiences through a program called Saturday Night Recovery Chatter. The conversations are posted to social media to provide connections for people seeking recovery.

Rick Rachwal believes the stigma surrounding substance use is “holding so many people back from talking about it.”

Burzinski agreed awareness is a key in the fight against the opioid epidemic. People in recovery need to know that “they’re not alone” and that a previous substance abuse or disorder “does not define” them.

Find treatment and resources for opioid addiction in Wisconsin

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services sponsors a Wisconsin Addiction Recovery Helpline, which offers free, confidential, statewide resources for finding substance abuse treatment and recovery services. Call 2-1-1 or visit 211wisconsin.communityos.org for more information.

IMPACT 211, which serves Southeast Wisconsin, conducts free assessments to determine an appropriate level of care and connects clients to treatment programs and recovery support services. The Access Point program is open to Milwaukee County residents aged 18 years or older. People who are insured or uninsured individuals are encouraged to ask about options. Call 414-649-4380 for more information or email [email protected] to schedule an appointment.

Wisconsin Watch’s Rachel Hale contributed reporting to this story. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us