The Virus That Shut Down Wisconsin: The Great Flu Pandemic of 1918

The speed at which the novel coronavirus has raced around the world, and the severity of the disease it causes, has sparked interest in humanity's last experience with a contagion of such scale.

April 7, 2020

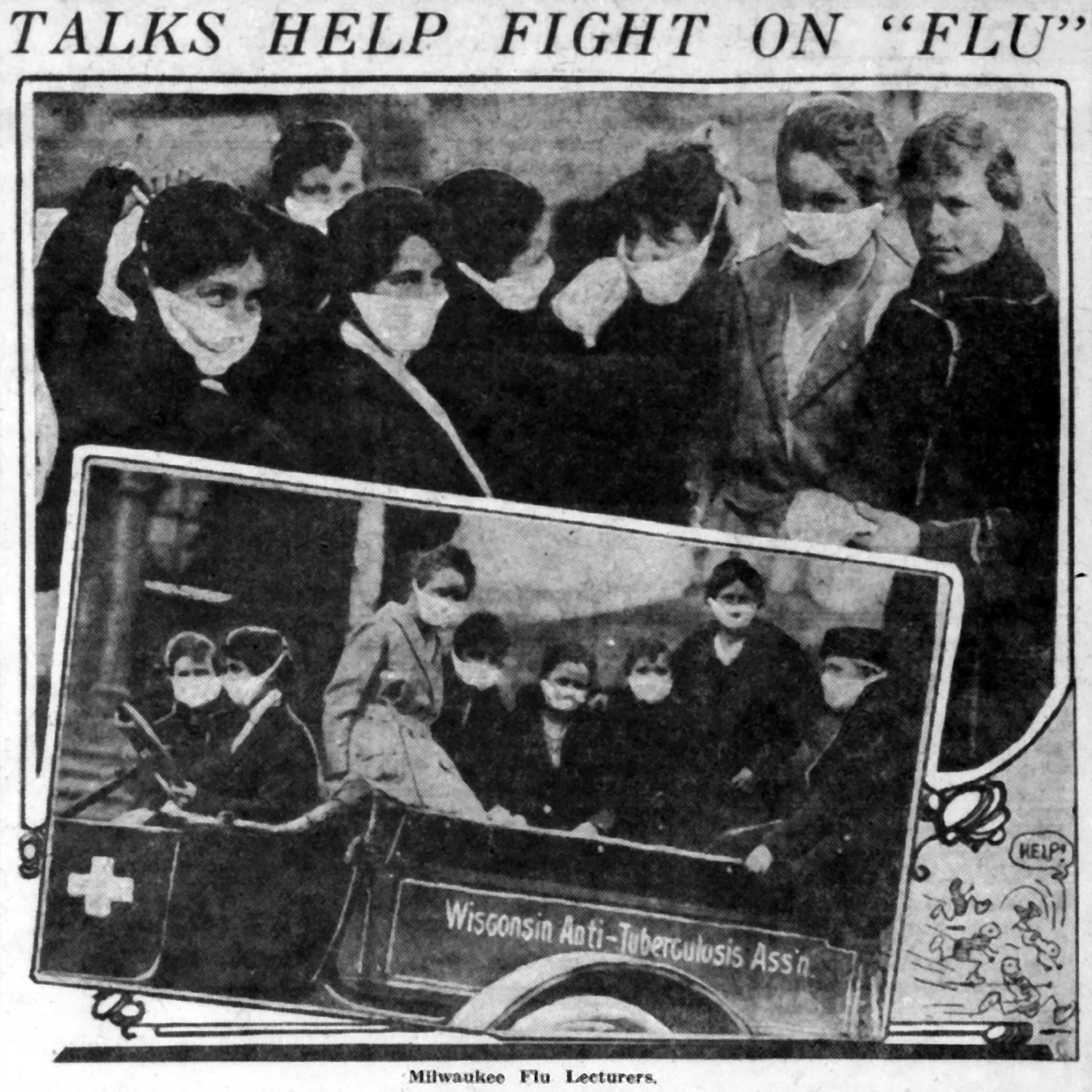

Edith Courteen stands by Milwaukee city ambulance in 1918 influenza pandemic

The speed at which the novel coronavirus has raced around the world, and the severity of the disease it causes, has sparked interest in humanity’s last experience with a contagion of such scale. Pandemics are not a relic of history — the past century alone has witnessed multiple worldwide bouts of particularly deadly strains of influenza in 2009, 1968 and 1957, as well as the much slower moving cataclysms of polio and HIV/AIDS. But it is the 1918-19 flu pandemic, nearly lost to living memory, that has captured the attention and interest of both the public health community and public at large in the age of COVID-19. Coming at the end of World War I, and known widely as the “Spanish flu” due to the fogs of war, the great influenza pandemic wrought worldwide devastation. This disease burned through Wisconsin, striking down the otherwise young and healthy particularly hard, and over the course of just a few months at the end of 1918, it was responsible for the death of upward of 8,500 people. Yet the state’s experience was atypical, and ultimately less severe than elsewhere around much of the United States, owing to the public health responses at the state and local levels. In its autumn 2000 issue, the Wisconsin Magazine of History published an article by Steven B. Burg, an assistant professor of history at Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania, that examines the many ways the flu of 1918-19 flu affected Wisconsin. This historical investigation details how people were struck down by the virus, explores how its effects differed from place to place and recounts how the public health measures put in place to address the disease were implemented and broadly embraced by communities and individuals.

In December 1918, the State Board of Health declared that the “Spanish flu” epidemic that had just swept the state would “forever be remembered as the most disastrous calamity that has ever been visited upon the people of Wisconsin or any of the other states.” A century later, the terror and devastation wrought by the tiny influenza virus still ranks it as one of the most terrible tragedies in the state’s history.

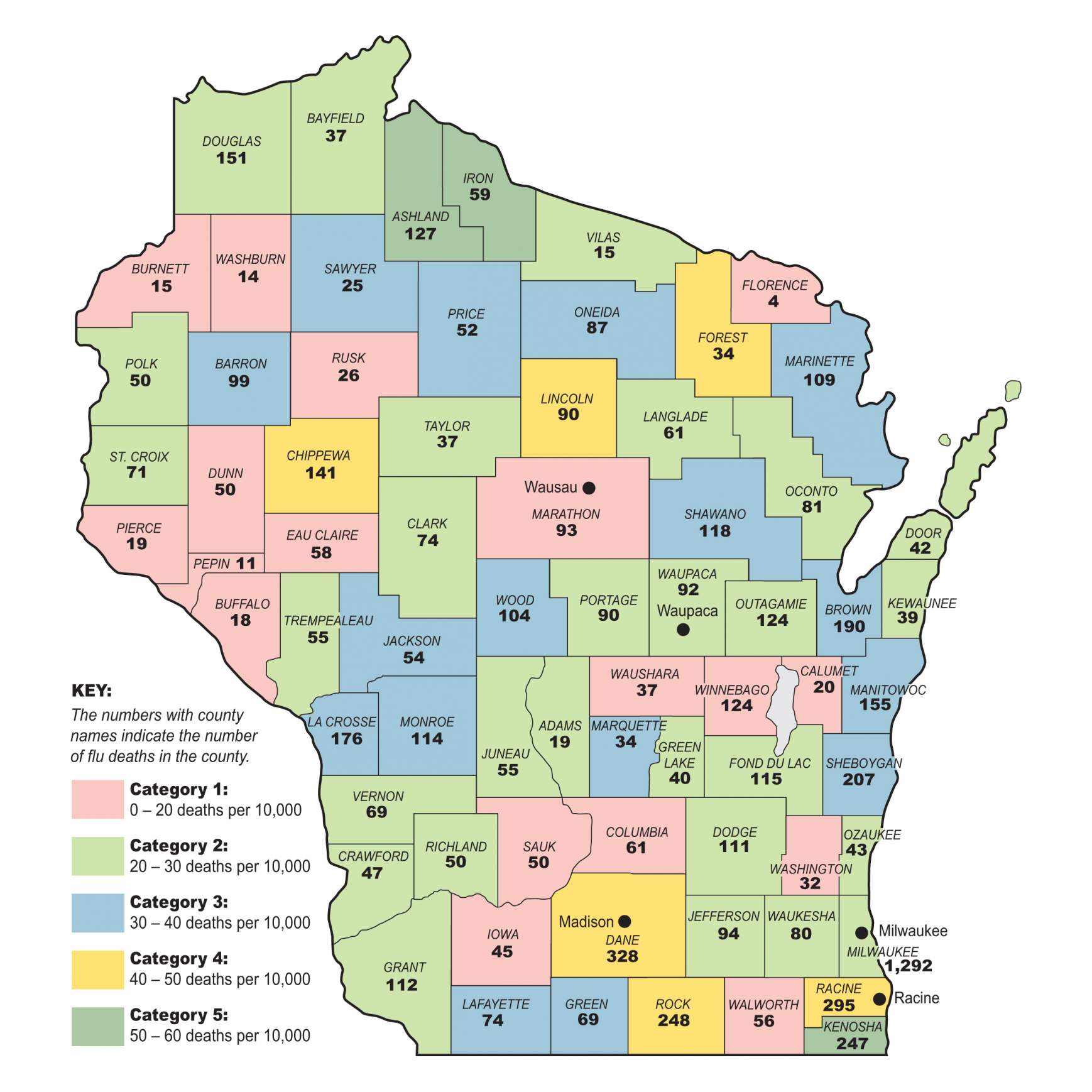

Even by modern standards, the scope of the epidemic remains staggering. Between September and the end of December 1918, influenza and related pneumonia debilitated almost 103,000 Wisconsin residents and killed 8,459 — approximately 7,500 more fatalities than would be expected from those causes in a normal year. To gauge the magnitude of the crisis, consider that more Wisconsin residents died during the six months of the influenza epidemic than were killed in World War I, the Korean War and the Vietnam conflict combined. Only the Civil War (1861–1865) and World War II (1941–1945) claimed more Wisconsin lives.

The influenza epidemic was, of course, not simply a Wisconsin tragedy but a global pandemic that killed more than 20 million people worldwide during the summer and fall of 1918, more than the total number of soldiers who died in four years of unremitting slaughter during World War I. It would ultimately kill 50 million. Everywhere, the disease’s arrival disrupted the routine of daily life and exacted a heavy human toll, leaving in its wake an unforgettable trail of death and destruction. One might assume that the scale and scope of the terrible tragedy would have secured the Spanish flu a somber but prominent place in the historical consciousness of all people unfortunate enough to have felt its fury.

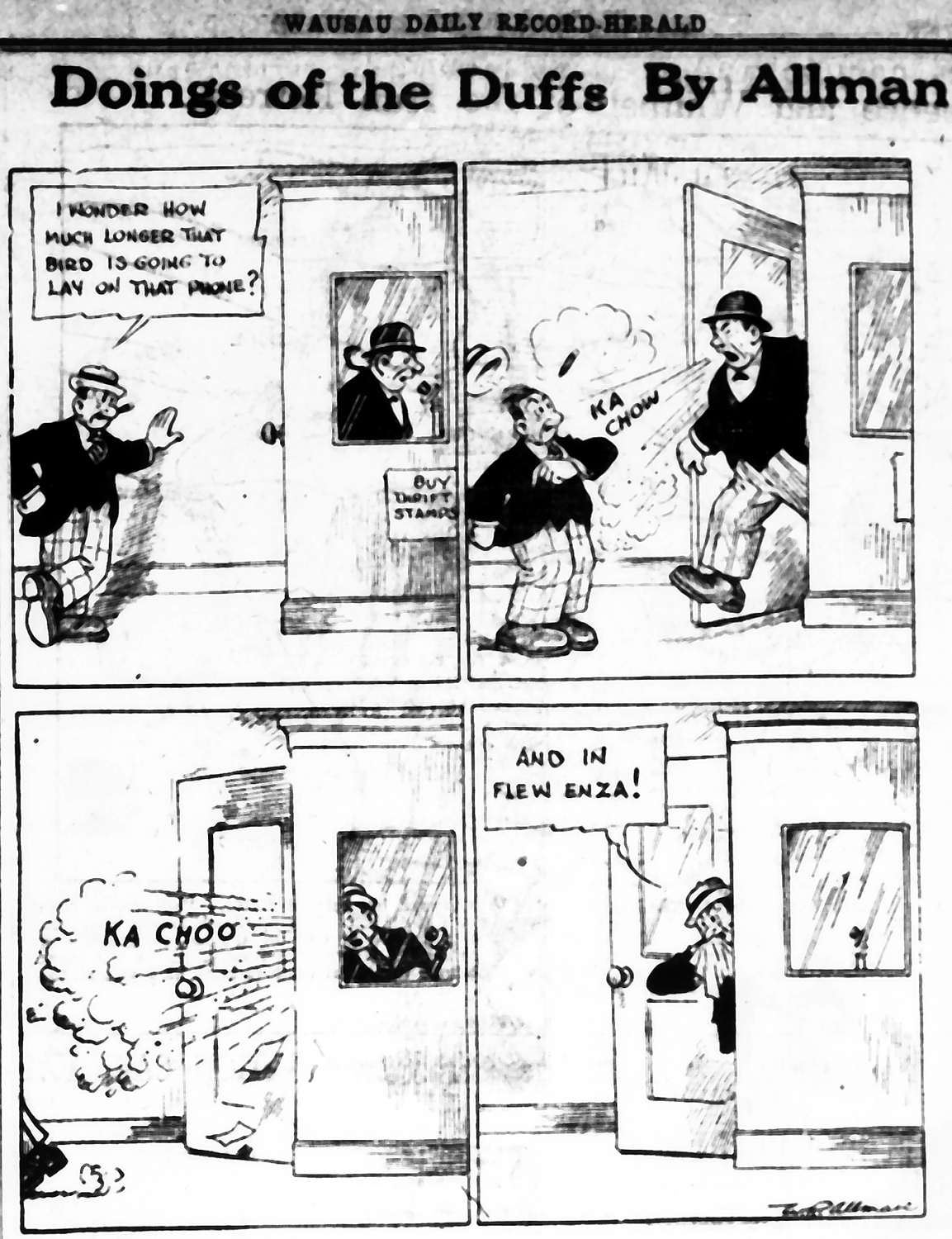

Surprisingly, however, the influenza epidemic lacks a place in the collective memory of Wisconsin similar to other notable local disasters, such as the Peshtigo Fire of 1871 or the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald in 1975, or even such national tragedies as the Great Depression or the Civil War. In part, this can be attributed to the elusive nature of the disease and the way it slowly and quietly spread across the Wisconsin landscape. No great ship sank, no armies clashed, no conflagration consumed a community.

Instead, the flu spread insidiously by means of ordinary coughs and sneezes, borne through communities along the channels of human contact, sending both young and old retreating to their beds. At the time, no one even knew exactly what caused the disease —the influenza virus would not be viewed under an electron microscope for another 15 years — nor how it spread, nor if it could be stopped. Exhausted and bedridden, its victims lay delirious while a microscopic battle raged between their immune system and the virus.

Once it passed, the fortunate ones returned to their daily lives to find that scores of their friends and neighbors had perished, many in the prime of their lives, stricken with a randomness that only added to the mystery of the disease. Rather than a presence, the epidemic was characterized by an absence — first as entire communities retreated to their beds, afterward when many people failed to return.

Moreover, the disease struck Wisconsin about six weeks before World War I ended on November 11, 1918, when newspapers were dominated by the rapid, victorious advance of Allied armies into Germany and by Liberty Loan drives at home, events that displaced other less dramatic news. There was little drama to the flu epidemic, particularly in its opening stages. The flu was silent, stealthy, invisible. It lacked the color of wartime exploits or the intrigue of diplomatic machinations.

Other than reporting the number of sick or dead, new regulations, obituaries, or the speculations of overwhelmed health officers, there was little the newspaper could say about the crisis. Compared to the war, the epidemic lacked neat objectives, glamorous heroes, or odious villains. Its competition with the war for public attention probably contributed to its faint presence in the popular memory.

Yet the great epidemic is worth remembering, not only for the terrible swath it cut through Wisconsin but also because the crisis it engendered permits unique insights into the nature of government, citizenship, civic life, and public health at the beginning of the 20th century. A state-level study is particularly apt. Wisconsin was the only state in the nation to meet the crisis with uniform, statewide measures that were unusual both for their aggressiveness and the public’s willingness to comply with them. Undoubtedly, those measures helped reduce the loss of life from the disease.

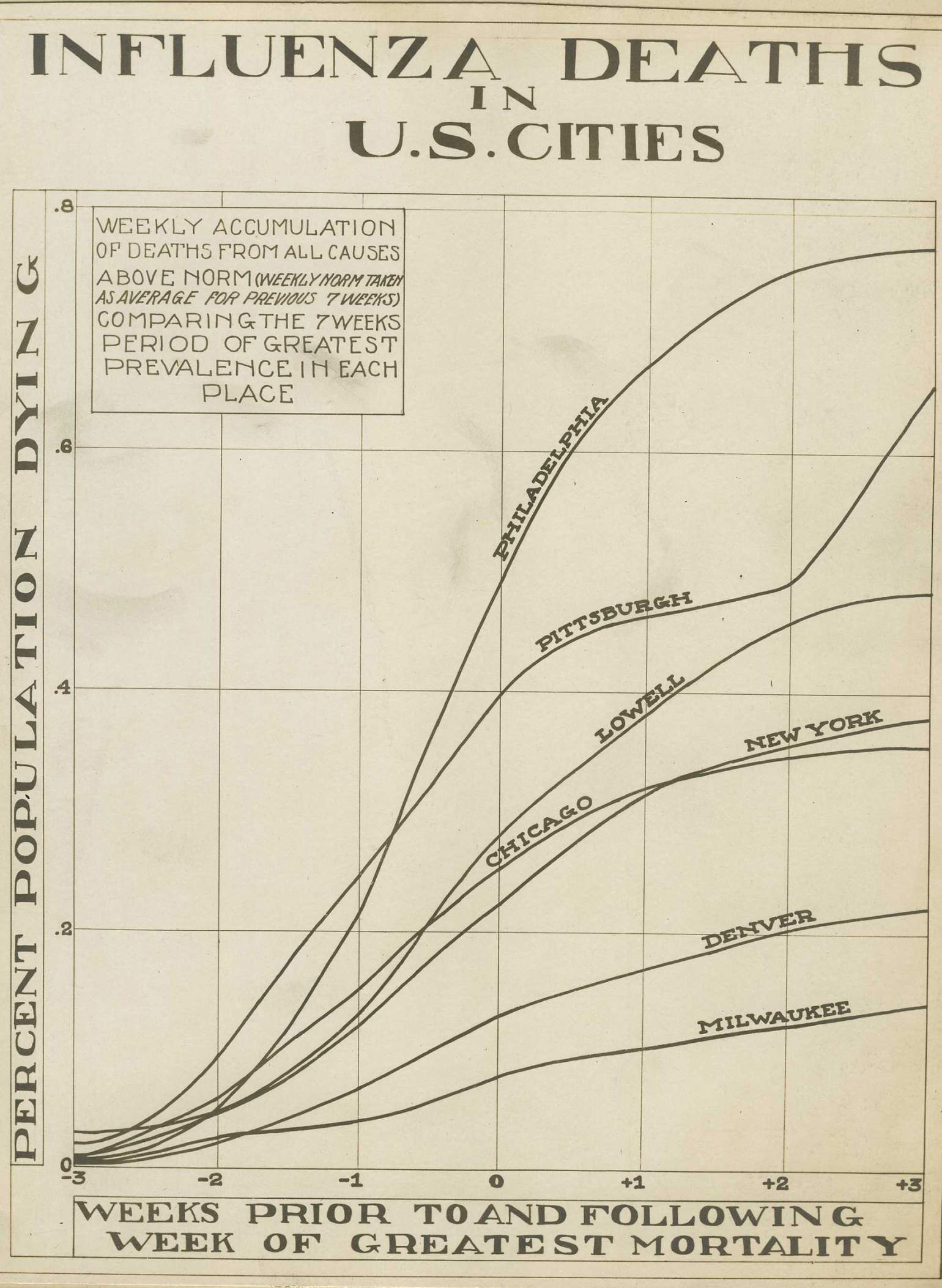

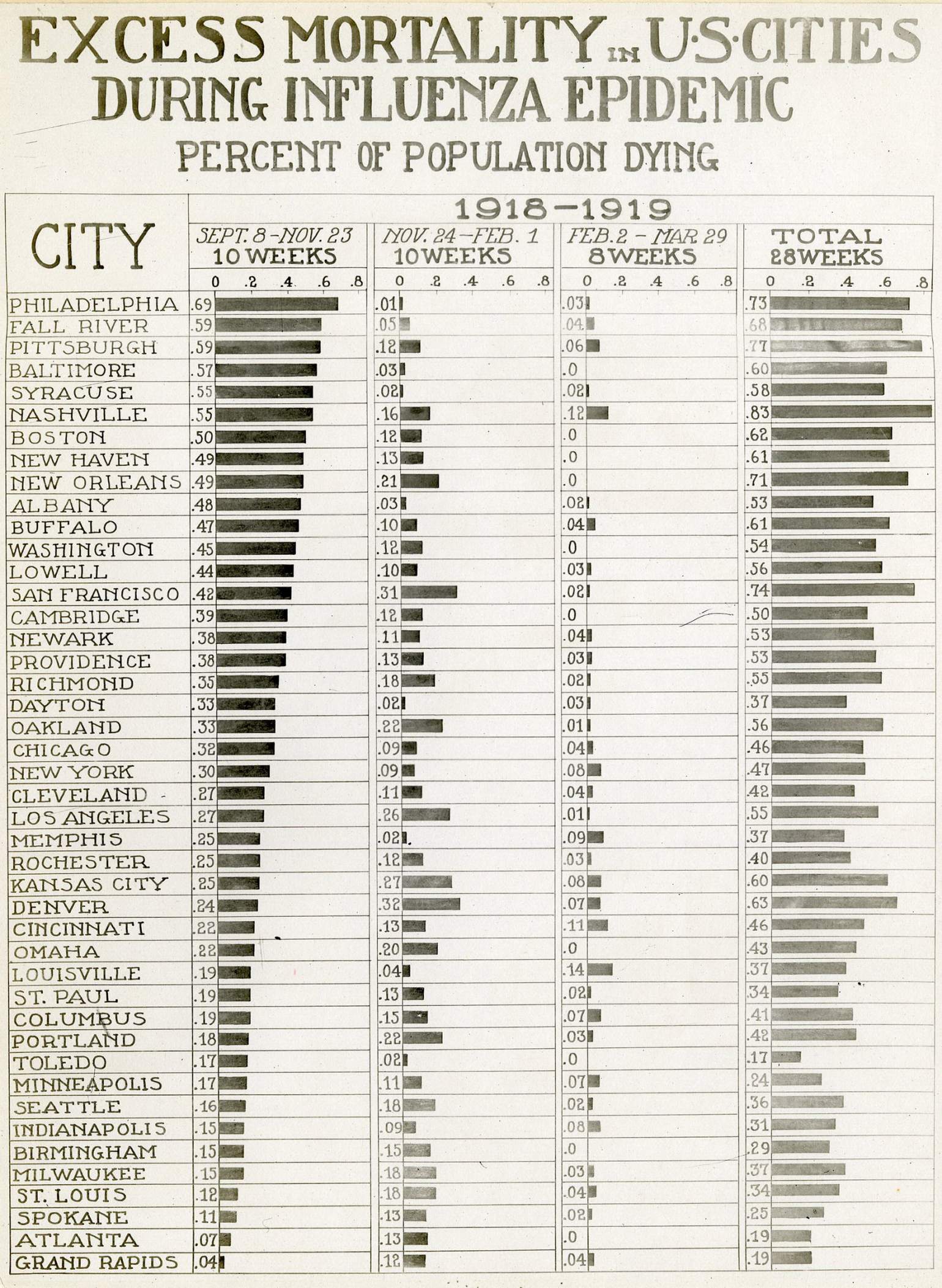

The states of the Upper Midwest proved most successful at preventing flu deaths, and though Wisconsin experienced a higher mortality rate than some other states in the region such as Michigan, Minnesota, and Indiana, it still emerged from the epidemic with one of the lowest death rates in the nation: 2.91 per thousand, compared with a national average of 4.39 per thousand.

While many factors may have favored Midwestern states, such as low population densities and the flu’s relatively late arrival in the region, civic and government action played a critical role in combating the disease. No state was adequately prepared for an epidemic of such proportions, but Wisconsin proved better prepared than most because of the state leaders’ foresight in making public health a policy priority.

Wisconsin’s extensive health infrastructure, combined with the public’s willingness to join the fight, saved thousands of lives and relieved untold suffering. The swift and effective campaign against influenza in Wisconsin reflected merely the latest fruits of a 40-year effort to improve the overall quality of life by protecting citizens from the scourge of infectious disease.

To this day, the origin of the epidemic remains obscure, but one theory suggests that the disease first emerged with a milder virus that subsequently mutated into a different, more lethal form. The less deadly strain of the flu may have made its first appearance at a military base in Fort Riley, Kansas, in the days following a violent dust storm on March 10, 1918. As the dust settled, soldiers began reporting to the base hospital with body aches, lethargy, coughing, and high fevers. By noon, 107 soldiers had been admitted. Within five weeks, the disease had spread through the nation’s armed services, incapacitating 1,127 soldiers and sailors and killing forty-six. But most of the afflicted soon recovered, resumed their military training, and then departed for France to join the American Expeditionary Force.

It seems likely that those American servicemen carried that mild form of the flu with them to Europe, where they shared it with their French and British allies as well as their German foes.

As the theory goes, sometime after the infected American troops reached Europe the microbes mutated into their more deadly and virulent state. The new, more lethal virus raged throughout continental Europe in the spring of 1918. It became known as the “Spanish influenza” probably because, as a neutral country, Spain did not censor its newspapers’ coverage, thus providing the rest of the world with the first news of the epidemic. By late spring, cases had appeared in Scotland and England. By August the new form of the virus had reached India, Southeast Asia, Japan, China, the Caribbean, and Central and South America, often progressing along major international trade routes.

Those infected by the new virus at first experienced an illness that resembled the common winter flu (or what many contemporaries termed “the grippe”), a winter ailment characterized by chills, fever, sore throat, headache, dizziness, muscle pain, watery eyes, general lethargy, and a short, dry cough. These symptoms generally dissipated after two or three days, though the cough and a general malaise might linger for another week or two.

What made the 1918 strain of influenza different, and deadly, were its rapid onset and dire complications. Common flu was ordinarily foreshadowed by symptoms and set in gradually. In 1918, the flu spread rapidly and often incapacitated its victims without warning. People in apparent good health would suddenly collapse with the flu; some died within hours. Furthermore, 20% of infected individuals—mostly those who resumed normal activities before the disease had fully passed — developed pneumonia. Up to half of those who caught pneumonia developed heliotrope cyanosis — a condition that filled victims’ lungs with a thick blackish liquid, turned their skin bluish-black, and usually proved fatal within 48 hours.

While the common flu often caused fatalities among the very old or the very young, the influenza epidemic of 1918 paradoxically took its most severe toll on those between the ages of 25 and 40 — men and women in their physical prime. There was no cure for this flu, and the only effective treatment was two weeks of undisturbed bed rest.

Worst of all, perhaps, the disease was highly contagious. It could be spread by contact with sick individuals, but influenza was also an airborne virus. It was borne from place to place within the respiratory systems of infected individuals who filled the air with the virus each time they coughed or sneezed. Unsuspecting bystanders inhaled the virus into their lungs where it multiplied and attacked them. If not exposed to sunlight, the virus could remain alive and airborne for hours, gently drifting through enclosed spaces on air currents or through ventilation systems.

A single sick person could contaminate everyone in an enclosed building or railroad car and leave the virus behind to infect even more after departing. Large, indoor public gatherings posed the greatest danger with the potential to infect hundreds or thousands, of people at a time. As fall turned into winter, the disease had even more favorable conditions for spreading, since people spent greater amounts of time indoors and closed their windows against the cold.

Though the milder predecessor of the influenza virus may have originated in the American Midwest, inexplicably North America was one of the last areas to be hit by the later and more deadly form of this flu virus. The disease probably traveled from Europe to the United States with returning American servicemen. On September 14, 1918, Boston reported the first case in the United States. Within a week cases appeared in other American cities with naval bases: Baltimore, San Francisco, Chicago, Mobile, and New Orleans. By the third week in September, the Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago reported 4,500 cases and 100 deaths, and Camp Grant in Rockford, Ill. — just twenty miles from the Wisconsin border — had 400 sick soldiers.

During the week of September 28, 1918, one of the first cases of influenza in Wisconsin appeared when two sailors from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station fell ill while visiting Milwaukee. Upon realizing that the two had the flu, the city health department immediately conducted a telegram canvass of the city’s physicians, who reported only 98 patients with bad colds or flu.

The health department requested physicians to report any new influenza cases immediately. Six cases were reported on September 26, 24 on September 27, 62 on September 28, and 97 on September 30. On October 2, 1918, a two-day decline in the number of cases was followed by the first four influenza deaths. Five days later, 256 new cases were reported, together with nine additional deaths. The flu then ripped through Milwaukee, infecting hundreds of people each day, peaking on October 22 with 588 new cases. After a brief lull in early November, the disease returned and infected thousands more Milwaukee residents before it finally trailed off in late December.

About the same time, other communities in southern Wisconsin reported outbreaks.

Madison had its first cases in early October. The flu began on the University of Wisconsin campus among participants in the military-run Student Army Training Corps (SATC). Because the epidemic first appeared on military bases, it was natural that Madisonians would assume that the SATC students might pose an influenza risk.

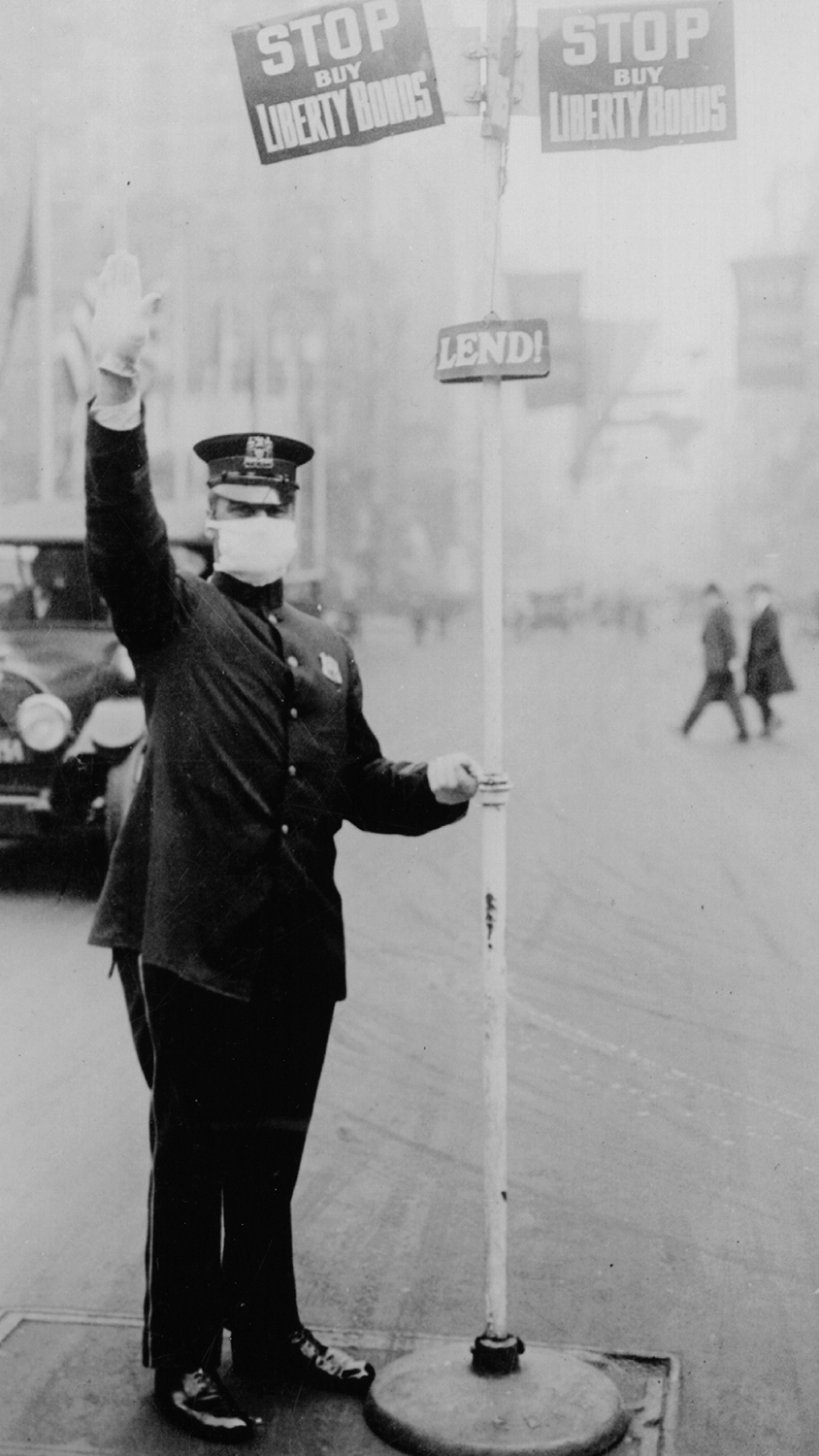

Rumors of the flu on campus began when SATC officials removed 322 engineers from a temporary barracks at the University Club in order to use their beds for an expanded infirmary, claiming they would need those beds to treat normally occurring maladies among the 4,000 SATC students. The creation of the infirmary alone may not have caused concern, but when ambulances with masked drivers and orderlies were seen transporting scores of sick young men to the hospital, people concluded that influenza had struck.

As rumors circulated, university, military, and city officials united in denying the presence of the flu. Dean Charles Bardeen of the University of Wisconsin Medical School explained that the 150 people had been removed to the University Club as a precautionary measure, and that most of the patients were merely suffering from bad colds. In an open letter to the university’s acting president, Edward A. Birge, Bardeen noted that “when college opens in the fall, we always have had a number of grippy colds among the students.”

Major E. W. McCaskey, commandant of the SATC, joined Bardeen, announcing, “We absolutely repudiate statements or rumors to the effect that there is a Spanish influenza epidemic in the SATC at the University.”

To calm the public, Bardeen issued a statement on October 8 predicting a steady decline in the number of cases and an improvement in the overall situation. He proudly declared, “There have not only been no deaths here, but there have been no students ill enough to make the medical staff even fear death.”

The following day, Arthur Ness — an SATC member and University of Wisconsin student — died at St. Mary’s Hospital. He showed the unmistakable signs of influenza-related pneumonia. It seems unlikely that either military or university officials intentionally tried to deceive the public. Rather, since the early stages of influenza were virtually indistinguishable from a bad cold, both had probably hoped for the best until the telltale blue-black corpses removed any doubt about the crisis they faced.

Influenza appeared in the Wisconsin communities and in the Lake Michigan port cities, then radiated along railway routes and highways. Madison’s first death (October 9, 1918) occurred a full week after Milwaukee’s first death; communities in the central and northern portions of the state often did not discover their first cases of influenza until the second or third week of October. Meanwhile, they merely waited and watched as the disease approached, creeping slowly across the landscape, leveling thousands as it passed.

Lacking any means of stopping the disease, Wisconsin’s cities and towns bubbled with both fear and optimism, fearful of the disease’s imminent appearance but hoping that somehow their community might be spared. Inevitably, hope gave way to despair as the grippe made its presence known.

Consider, for example, the epidemic’s progress from the perspective of residents of rural Waupaca, the county seat of Waupaca County, midway between Appleton and Stevens Point. For weeks residents had read about the flu in the newspaper, first as it hit military bases, then as it spread into the nation’s cities. It is not hard to imagine that at first the epidemic appeared as something removed from east-central Wisconsin, a vague and distant threat confined to military bases and metropolitan areas. But before long, the threat loomed closer to home.

In early October, Waupaca civilians recruited to work in the military factories of Milwaukee, Racine, and Kenosha, the so-called “honor men,” were told not to leave Waupaca County because of the seriousness of the epidemic in southern Wisconsin. About the same time, the newspapers began running obituaries of local boys who had left for war work or military service and then died from influenza. The first came on October 3, 1918, when Wallie Edward Barwell of Waupaca, age twenty, died in Racine. A week later, the paper carried four obituaries of local servicemen struck down by the flu: Fred H. Brown of Saxeville and Robert Huggins of Almond, both stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Training Station, and two brothers, Rheinold and Leo Ferg of Symco, stationed in Racine.

During the second week of October, just as the fall potato harvest hit full swing in that region of Wisconsin, influenza tore through Waupaca. One doctor alone reported 22 cases in seven days. Locals nonetheless remained hopeful that they might dodge the worst of the epidemic.

The editor of the Waupaca County Post encouraged his readers to use positive thinking to beat the flu. He reminded the city’s residents of their good fortune, noting that “few cases have appeared here, none yet fatal” and predicting that it was “very probable” the city would escape the epidemic.

About the time he was writing that editorial, 14-year-old Grace Larson caught a cold while picking potatoes with her sister. Following a quick recovery, she suddenly fell ill with pneumonia and died at her home on the evening of Tues., Oct. 15, 1918. She was the city’s first flu casualty.

As events in Milwaukee, Madison, and Waupaca help illustrate, the flu arrived in each community under different circumstances, and the timing, duration, and severity of the onslaught varied from town to town and region to region. But in each case it was a death from pneumonia exhibiting the distinct symptoms of heliotrope cyanosis that removed any doubt that the flu had struck—and no county in Wisconsin completely escaped the disease’s fury.

Yet Wisconsin did not flinch in the face of the epidemic. Indeed, the state responded with one of the most comprehensive anti-influenza programs in the nation, one made possible by the existence of a strong state public health board and a well-coordinated statewide public health network, some forty years in the making.

On March 31, 1876, the Wisconsin legislature had created the State Board of Health, a seven-physician panel responsible for “general supervision of the interest of the health and life of the citizens of the state,” making Wisconsin the tenth state in the nation with such a board, the first having been put in place in 1869 by Massachusetts. The legislature also granted the board unusually broad powers, allowing it to impose statewide quarantines unilaterally in times of public health emergencies as well as to issue “rules and regulations for the protection of the public health.” Because the full board convened only twice a year, this meant that one person — the state health officer — possessed the authority to issue statewide health orders in times of crisis.

In 1883, the state had also required that every town, village, and city in the state create a local board of health and appoint a public health officer. As a result, 1,685 local boards of health existed when the flu epidemic erupted. While some public health officers lacked experience, administrative skills, or even medical expertise, at the very least they ensured that every community had a local agent who could serve as a liaison between the State Board of Health and local governments, and who was responsible for the local enforcement of health regulations.

Fortunately, many of these local health officers brought some knowledge and skills to the position. Many had dealt with infectious diseases such as scarlet fever, diphtheria, smallpox, cholera, and typhoid; others had learned basic public health procedures through state-sponsored workshops and publications. This cadre of local health officers enabled communities throughout the state to mobilize independently against the flu.

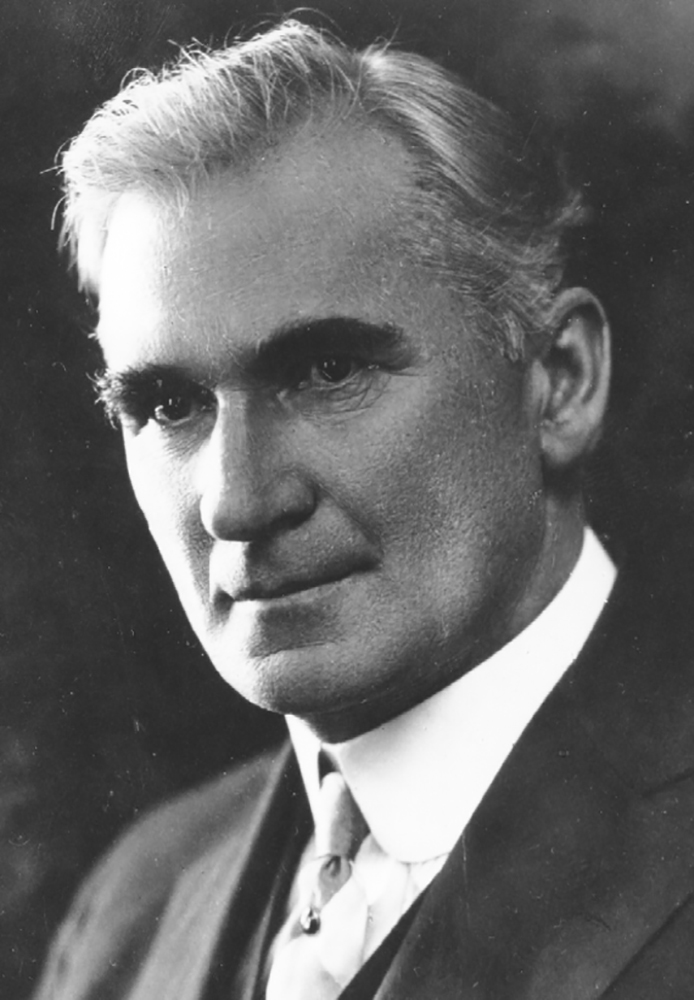

State Health Officer Dr. Cornelius A. Harper took full advantage of the state’s public health infrastructure when the influenza threat loomed. He was a Madison physician whom Governor Robert M. La Follette appointed to the board in 1902, and he strongly favored an activist role for government in improving public health, working tirelessly for more stringent regulations and improved public support for education and health services.

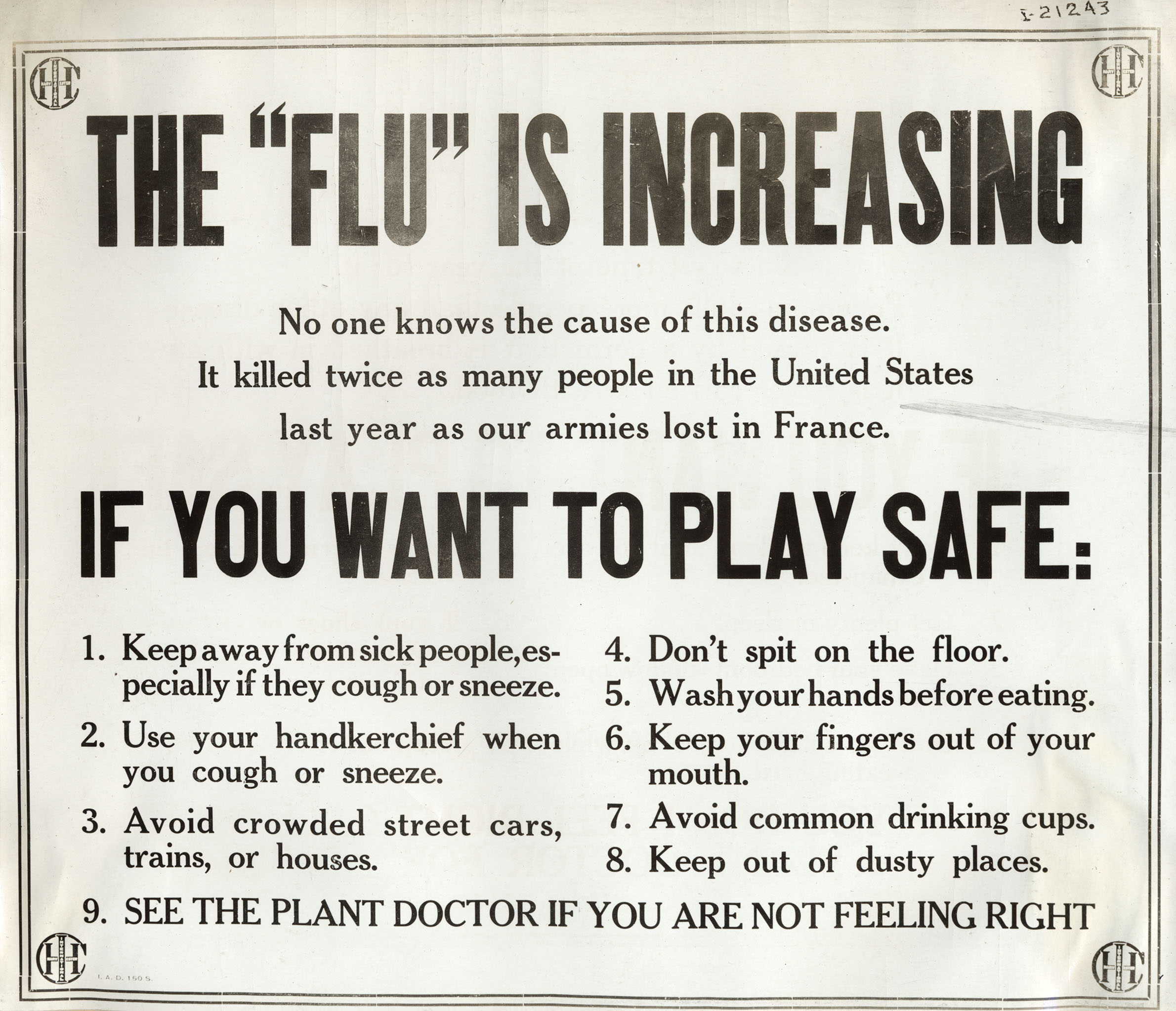

Even before the influenza epidemic hit, Harper called for a statewide educational campaign aimed at informing the public that anyone with a severe cold should stay at home and away from public gatherings. He hoped public cooperation would be forthcoming because of the severity of the crisis; but he also encouraged local governments to consider more aggressive measures to shape public behavior.

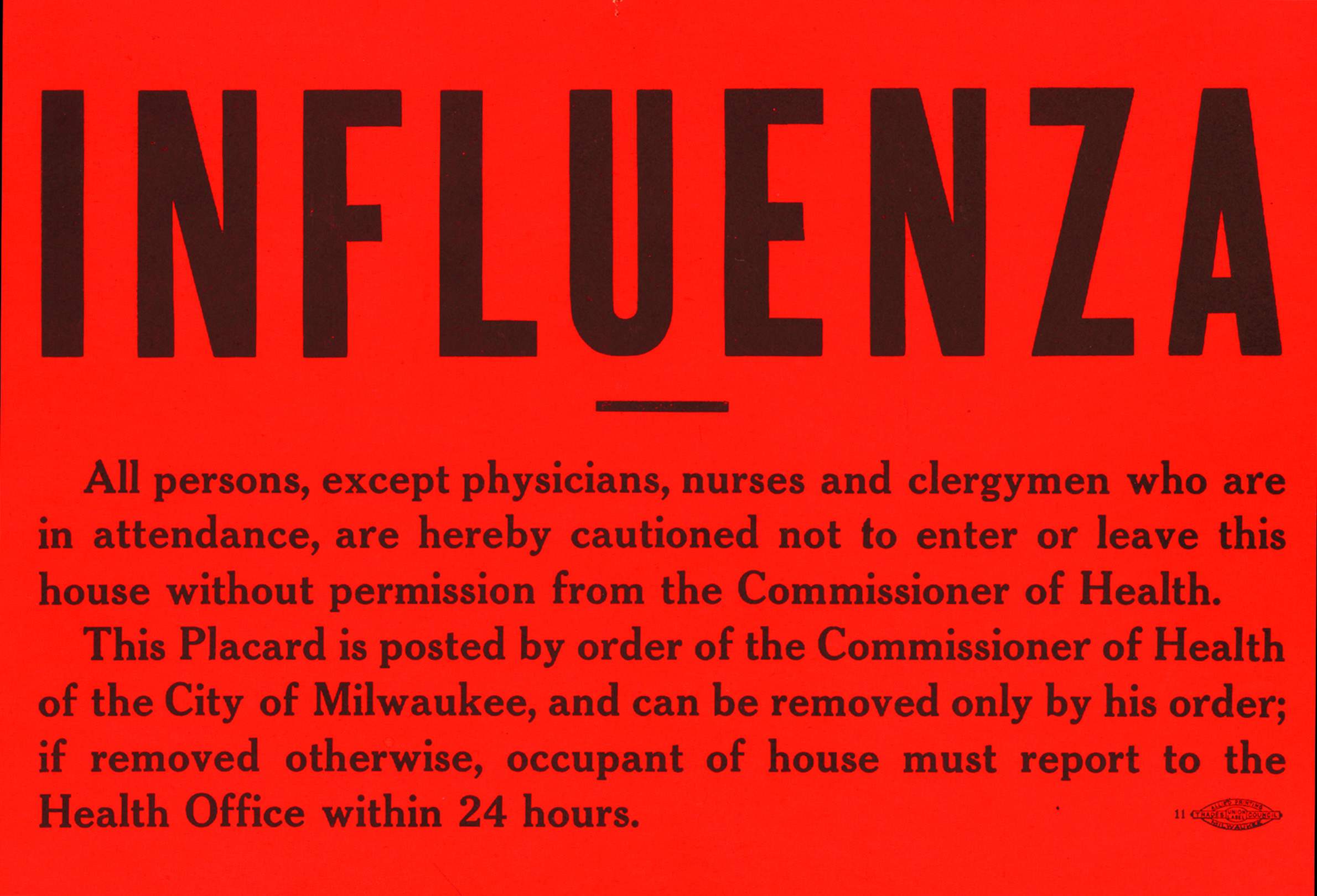

As he observed in a widely distributed pamphlet, “If public sentiment is sufficiently strong to support this program, people who have influenza or a severe cold will remain home voluntarily. If they do not, it may be necessary in some localities for the local board of health to provide for the isolation of such persons and if necessary, provide for the placarding of the premises.” (Health officials commonly placed placards on the outside doors where infected individuals lived, thus enforcing and publicizing quarantines of contagious diseases.)

The board also urged citizens voluntarily to avoid “theaters, mass meetings, closed and crowded cars and close contact with other persons, especially those who appear to have severe colds” and to refrain from sharing objects used by sick people. Teachers were instructed to send sick pupils home and to report any illness immediately to the local public health officer. The board also recommended against public viewing of corpses at flu-victims’ funerals or the holding of wakes in the homes where they had fallen ill. Sanctions were issued against public coughing, public spitting laws were to be strictly enforced, and kissing was discouraged as a potentially dangerous activity.

On October 10, 1918, the deteriorating situation statewide led Dr. Harper to take the more drastic step of ordering all public institutions closed. This followed a recommendation issued by U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Rupert Blue suggesting that public health officers might consider closing public institutions should local conditions warrant such action; but nowhere except in Wisconsin was such an order issued statewide or in such a comprehensive fashion.

After conferring with Governor Emanuel Philipp, Dr. Harper issued a statewide advisory, ordering all boards of health “to immediately close all schools, theaters, moving picture houses, other places of amusement and public gatherings for an indefinite period of time.” Within a day, virtually every local government in Wisconsin had cooperated and put the order into effect.

The Board of Health fully realized the magnitude of the step it had taken. In its bulletin the following month, it noted: “Never before in the history of the state has it become necessary to close schools, churches, theaters, saloons; in fact, everything except factories, offices, and places of regular employment. . . .”

From a modern perspective, it seems unthinkable that a single appointed bureaucrat would possess the independent authority to issue a binding statewide order that shut down all public activities across the state. Yet at least three factors made the climate of 1918 different than that of today.

First, by October 10, Wisconsin residents had been following the progress of the epidemic for at least a month as it ravaged military bases and states to the south and east. By the end of September, more than 1,000 residents of Boston had already perished from influenza; by early October hundreds of thousands of Philadelphia residents lay sick or dying. Most Wisconsinites probably knew enough about the disease to support measures thwarting it.

Second, the preparations against the flu melded into the larger public mobilization in support of the war effort. Dr. Harper’s closing order merely extended the demands for sacrifice and cooperation that animated a general wartime spirit. As one editor noted, “Had this country been at peace … it is likely that the present epidemic would not have excited so much attention and it is certain that no such vigorous effort would have been made to combat it.”

Finally, the epidemic struck on the heels of the Progressive Era, a time in American life — and nowhere more so than in Wisconsin — when the faith in the power of government and experts for improving the quality of civic life stood at an all-time high.

This is not to say that there was absolute compliance.

In the first few days after his order went out. Harper spent much of his time instructing local officials by telephone and telegraph to enforce it, particularly in the central and northern parts of the state where the flu had not yet struck. In the exact center of the state, for example, Wausau delayed closing its schools for several days because local officials did not realize that the order was mandatory. The confusion stemmed from the poor wording of the telegram Harper had sent to local health officers, which included the phrase, “Order issued as an advisory order. Local boards of health to use own judgment in closings.”

In fact, Harper wanted the closing order to be enforced universally and immediately; but he also wanted to give local officials some latitude in how they went about implementing it. Unfortunately, many local health officers interpreted his telegram to mean that the timing and extent of the order’s enforcement were left to their discretion.

The confusion had its most dire consequences in Wausau.

When the Wausau board of health decided to keep the city’s schools open for a week, a member of the area draft board and one of the city’s most prominent citizens and politicians, Walter B. Heineman, telephoned Dr. Harper to complain that city officials were jeopardizing the draft board’s ability to muster its quota of recruits. Dr. Harper told Heineman to tell the Wausau board of health it should close the schools immediately, a message Heineman relayed by telephone to the mayor, John Sell.

The next day, Heineman wrote a letter to the mayor that was published in the newspaper summarizing his conversation with Dr. Harper. According to Heineman, Dr. Harper said that Wausau was the only city in the state not to follow the order, that it must close its schools, that he would quarantine the entire city if it did not, and that “failure to comply with it [the closing order] would lay any community open to criticism as being pro-German.”

Wausau officials were deeply offended at having their patriotism thus impugned. A series of phone calls did little to improve matters, so Harper finally decided to invite the Wausau officials to Madison for a face-to-face discussion. Before the meeting could occur, however, the epidemic hit Wausau, forcing local health officials to direct their energies to the more urgent matters of caring for the sick and dying.

Unfortunately, the misunderstanding had kept the closing order from being enforced, and as a result of the mingling of the sick and well the city experienced a large number of cases all at once. Dr. Harper, who continued to protest that he was guilty of nothing worse than miscommunication, conceded that the flu onslaught in Wausau “became one of the most difficult problems of any community in the state.”

A more deliberate form of opposition to the closing order came from a handful of religious leaders who questioned the wisdom of closing churches in a time of crisis.

Virtually all churches of every denomination closed, though at least one priest, Father J. M. Naughtin of St. Rose Church in Racine, refused to close the church even amid demands from concerned local residents and the State Board of Health. Dr. Harper eventually raised the issue with Archbishop Sebastian Messmer of Milwaukee, who assured him, “Doctor, that church will be closed.”

The archbishop then issued a letter to all clergy in the archdiocese conceding that closing their churches would be “a great religious sacrifice upon the Catholic people” but that under the circumstances “we must obey the order.” He then decreed: “Hence, until the order is recalled, there will be no public services in our churches, Sundays or weekdays. The main doors of our churches will be locked. Bells may not be rung except for the Angelus, but funerals may be held and marriages performed in the churches, with a low Mass, provided only near relatives of the parties be present.”

Priests could hear confession and give holy communion, and individuals could offer private prayers in the churches “provided no large numbers of people are present at any given time.” However, all confirmations would be postponed and all Catholic schools closed when ordered by local officials. St. Rose, and every other church in the diocese, thereupon closed for the duration of the epidemic.

Archbishop Messmer’s actions did not completely silence opposition to the closing of churches.

For example, an editorial in Milwaukee’s Catholic Citizen questioned placing churches “on a par with theaters, moving pictures, and dance halls, saloons and the like” and declared that the “closing of houses of worship is practical apostasy.”

The Reverend H. C. Hengell, rector of St. Paul’s University Chapel in Madison, emerged as an equally vocal critic. He declared that the closing order exceeded “Prussian bureaucracy at its worst” — strong words indeed when wartime anti-German sentiments were at their height. Hengell also believed that the order would do “irreparable harm to religion” and that its enforcement represented “the crying sin of the age.”

Yet overall, opposition to the closing order was rare, and deliberate refusals to enact its provisions were even rarer. Overwhelmingly, the people and institutions of Wisconsin observed the regulations, and many went even further by mobilizing their own local efforts to educate the public about the disease and to assist the afflicted.

Perhaps the most impressive effort took place in Milwaukee, the city that posed the greatest health risk with its large population: 373,857 people in the city proper and another 59,330 in the surrounding county, representing fully one-fifth of the state’s population, and densely packed at an average of 1,899 persons per square mile. Elsewhere, the flu had proved particularly fierce and deadly in just such compact urban environments. The course of the epidemic in Milwaukee would be a significant factor in determining how the state would fare.

In fact, Milwaukee proved to be one of the best prepared cities in America for meeting a major public health crisis.

Since the mid-19th century, municipal reformers had pressed for government action to address problems such as smallpox, tainted milk, and uncollected refuse, and by 1918 the city had established an efficient health department, a multi-partisan political coalition supporting public health work, and a strong civic commitment to such initiatives.

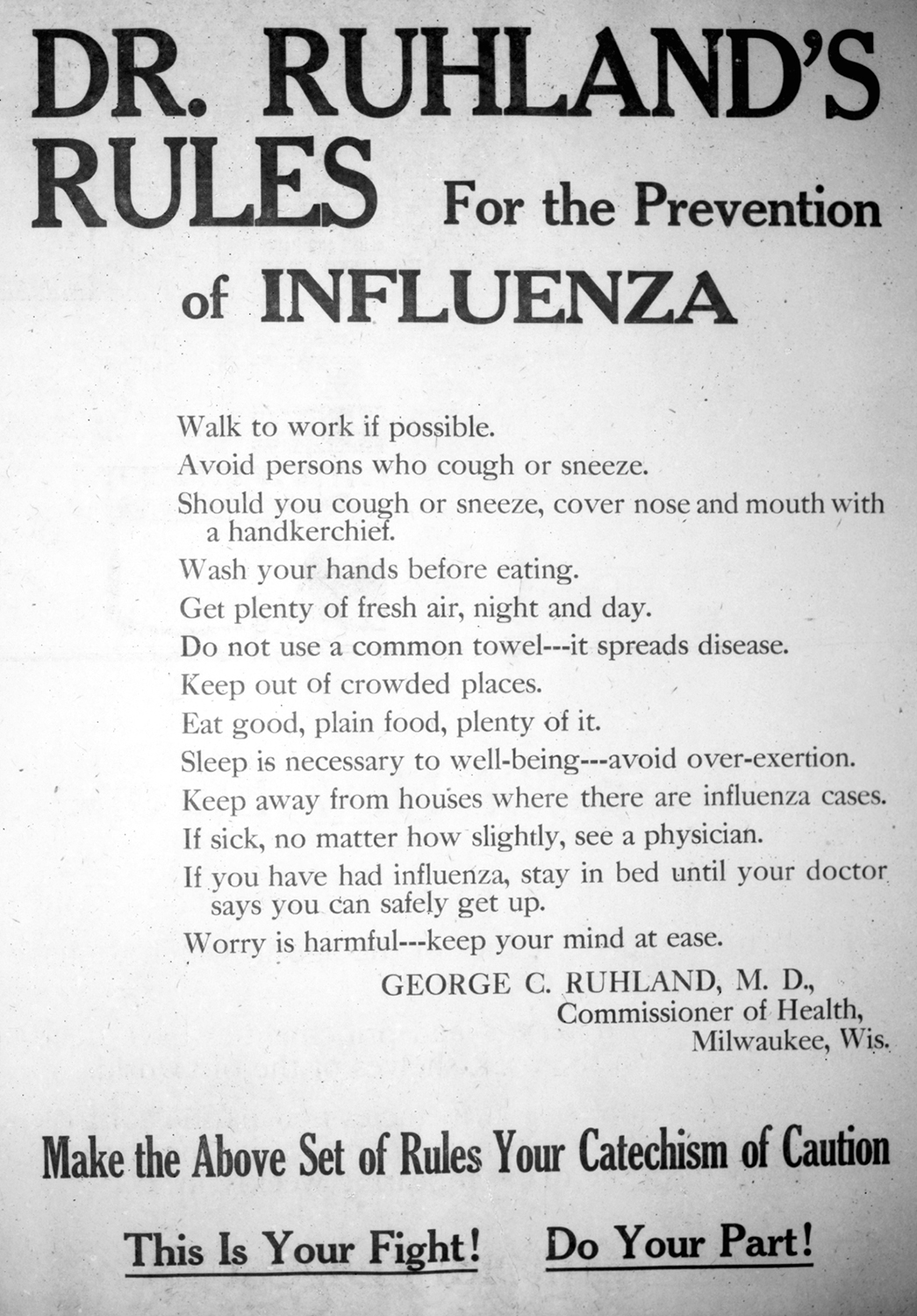

Leading the battle against the flu was City Health Commissioner George C. Ruhland, a consensus-building public servant whose thoughtful approach and skillful leadership won the full backing of both government and business leaders, and of the Socialist mayor, Daniel M. Hoan. Indicative of Ruhland’s political skills was his swift appointment of a four-man advisory committee to oversee the anti-influenza campaign. He appointed two medical doctors, Louis F. Jermain and Hoyt E. Dearholt, and two prominent businessmen, Col. Otto H. Falk and Carl Herzfeld, a balance that helped bolster his credibility among the public and the business community. When Ruhland approached the Milwaukee city council for financial support, the council held a special meeting as soon as legally possible and granted him $15,000, an amount promptly matched by the county board.

This broad-based support among business leaders, local governments, and the public enabled Milwaukee to mount an extensive education program.

Early in the campaign, health department officials met with the city’s newspaper editors, all of whom agreed to help by not publishing stories that might create a panic and by printing educational stories and editorials urging compliance with the influenza campaign.

The city’s health department complemented the newspaper coverage by producing informational posters, placards, and pamphlets that the Boy Scouts distributed around the city. An easy-to-read, four-page leaflet created by the health department was printed in English and several foreign languages (almost certainly including German and Polish) and circulated among the city’s large immigrant communities.

Numerous businesses also focused on influenza education. The streetcar companies printed and posted cards in all their cars admonishing the public: “Don’t cough, don’t sneeze, don’t spit; use your handkerchief.” Several large employers printed and distributed influenza information to their employees. And with the schools closed, the city’s teachers selflessly conducted a house-to-house canvass to visit the sick and count the number of influenza cases. The canvass risked exposing teachers to the virus, but more importantly, it helped spread information and enabled the health department to monitor closely the state of the epidemic.

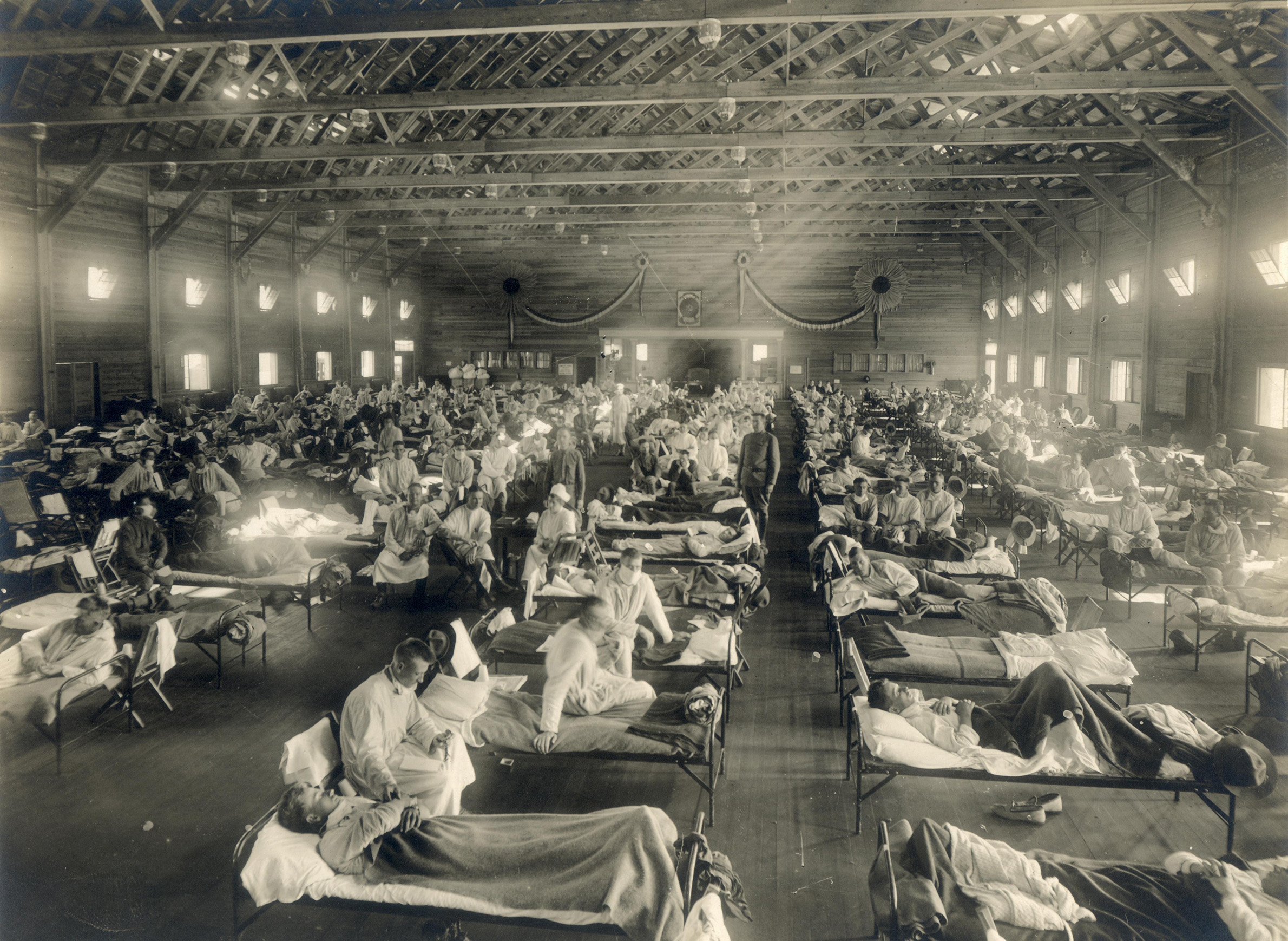

Like the rest of the state, Milwaukee faced a shortage of hospital beds and medical personnel, a crisis compounded by the large numbers of doctors and nurses who were serving in the armed forces. Those who remained worked long hours and treated enormous numbers of patients, aided predominantly by women volunteers and civic groups who helped establish emergency medical facilities and who provided volunteer labor.

The city secured two large private residences and the city auditorium as emergency hospitals; these were outfitted as hospitals by the members of the Citizens’ Bureau of Municipal Efficiency. To free up the county health nurses to help flu victims at the emergency hospitals, the student nurses and instructors of the Wisconsin Anti-Tuberculosis Association took over their day-to-day duties. A large number of volunteer Red Cross nurses’ aides joined the public health nurses at the hospitals, as did many school nurses, volunteers from the Wisconsin State Guard, and 10 sailors from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station.

Young women from wealthy families who owned automobiles volunteered as ambulance drivers with the Red Cross motor corps. Their responsibilities proved particularly arduous, including “driving the ambulances from early morning until way after midnight on some occasions” and “carrying patients rolled up in blankets down narrow stairs where the stretchers cannot be used.”

These citizen volunteers provided resources that allowed Milwaukee health officials to manage the crisis far better than would have been possible with only health professionals and their limited staff. Undoubtedly they saved thousands of lives.

Cities elsewhere in Wisconsin mobilized for the crisis on a smaller scale but with equal vigor.

In Wausau, medical personnel, government officers, and civic organizations joined forces to meet the city’s particularly fierce outbreak. As soon as the flu struck, representatives of the public schools, the Boy Scouts, the Federated Charities, the Wausau children’s infirmary, the Red Cross Home service, and the Wausau board of health began meeting to coordinate their response to the crisis. The group decided to launch a citywide census of influenza cases to identify the sick and to monitor the disease’s progress.

Seventy women volunteers began touring the homes of the city, whisked about in the automobiles of the Woman’s Motor Squad, distributing health literature, recording the number and condition of sick persons, and noting whether they needed assistance. They soon discovered that the epidemic was taking a heavy toll on domestic life. In many homes, overworked, exhausted mothers were struggling to care for multiple sick children; in others, not one adult was fit to cook, clean, or tend the sick and dying.

In response, the woman’s committee of the Wausau Defense Council and the Federated Charities began recruiting volunteers to aid sick families and assist overtaxed mothers with household chores. Several of the young women who volunteered in the homes of the sick took time off from their jobs, including about a dozen volunteers from the Girls’ Training Corps who explained to their employers that their anti-influenza labor contributed to the war effort.

In just this manner, many Wisconsin residents seem to have envisioned their efforts as a natural extension of the wartime home-front mobilization.

Other groups also aided the Wausau effort.

The Ladies’ Literary Society sewed gauze masks for public health workers; the Red Cross Home service recruited young women to work as volunteer nurses; the Woman’s Benefit Association of the Lady Maccabees printed and distributed informational cards. The domestic science teachers of the public schools and the Marathon County Training School for Teachers prepared meals for those too sick to cook for themselves.

Wausau businesses also lent a hand. The Curtis and Yale Company tried to stop the spread of disease among its employees by issuing them gauze masks, and the Employers Mutual Liability Insurance company gave its customers placards for display in their homes or factories: “Cover up each cough and sneeze; if you don’t you’ll spread disease!”

Even with such a community effort, the severity of conditions in Wausau led the Red Cross to request additional assistance from the State Board of Health. On November 5, 1918, the Board of Health sent L. E. Blackmer of the University of Wisconsin Extension to take charge of the effort there. He immediately addressed a meeting of ward chairmen of the County Council of Defense describing how citizens could assist the city’s physicians. He also established a system of card files for monitoring the progress of all known cases and for ranking their severity. Local officials granted him full authority to adopt any measures he believed would help combat the disease.

The Wausau example provides a useful illustration of how state and local government joined forces to counter the flu. In most cases, the State Board of Health provided local authorities with guidance and technical information; but in a few extreme cases, the state sent experienced public health professionals to work directly with local officials. The small staff of the State Board of Health made such interventions rare, but they make clear that Wisconsin’s response to the epidemic truly was a joint state and local effort.

The state’s smaller cities, towns, villages, and rural hamlets were of course far less likely to have the political or civic infrastructure to mount formal anti-influenza campaigns. Instead, most local governments enforced the closing order, then relied on local doctors, nurses, hospitals, and clinics to care for the sick, a response that often proved inadequate because of the shortage of health professionals and the great distances that often existed between patients’ homes and from the homes of the caregivers.

In Waupaca, just 50 miles south and east of Wausau, fully one-quarter of the city’s 2,789 residents came down with the flu, and though the city’s doctors and nurses worked almost nonstop, they still could not visit all the sick people. As one reporter commented following three months of intense work battling influenza, the city’s “doctors and nurses have been driven to their limit.” And as busy as the doctors were, the undertaker was even busier. He found himself conducting funerals almost every day — sometimes several a day — leading the Waupaca County Post to note “the strain on the undertaker has been enormous.”

In some communities, of course, the undertaker himself fell ill or died, creating a nightmarish backlog of postponed funerals and stockpiled coffins awaiting burial.

A resident of Waupun, on the Fond du Lac-Dodge County border, long afterward recalled his baby sister’s funeral: “Never within my memory were so many people of the town stricken at the same time … So heavy were the fatalities that the sole undertaker in town could no longer cope … Father Paul, our priest, had buckled under the weight of the flu and thus could not give words of comfort to the survivors. Margaret’s tiny coffin — it was no more than a simple box — had rested on a little table by a window. Mother, crying softly, whispered that we should say goodbye to our sister. We chorused her name and then my Father, almost casually, tucked the coffin under his arm and left the room. That was our sister’s funeral, stripped to the one absolute essential: burial.”

In the countryside, the shortage of doctors and nurses meant that medical care was even scarcer, and that assistance came primarily from families, friends, and neighbors. As farm family members fell ill, those who remained healthy found themselves faced with the enormous task of tending the sick and running a farm short-handed. One or two family members might need to cook, clean, and care for a large family while also watching over the family’s livestock, a job that might entail feeding, milking, and delivering to market the milk of twenty or thirty cows.

In some areas where the flu had incapacitated entire households, a few farmers cared for as many as a dozen families and their livestock until the flu passed. Wisconsin’s rural communities depended on the strength and compassion of individuals voluntarily assisting their needy neighbors.

Although the efforts of the state’s large and small communities relieved enormous amounts of human misery, they could not stop the spread of the disease or reverse its symptoms.

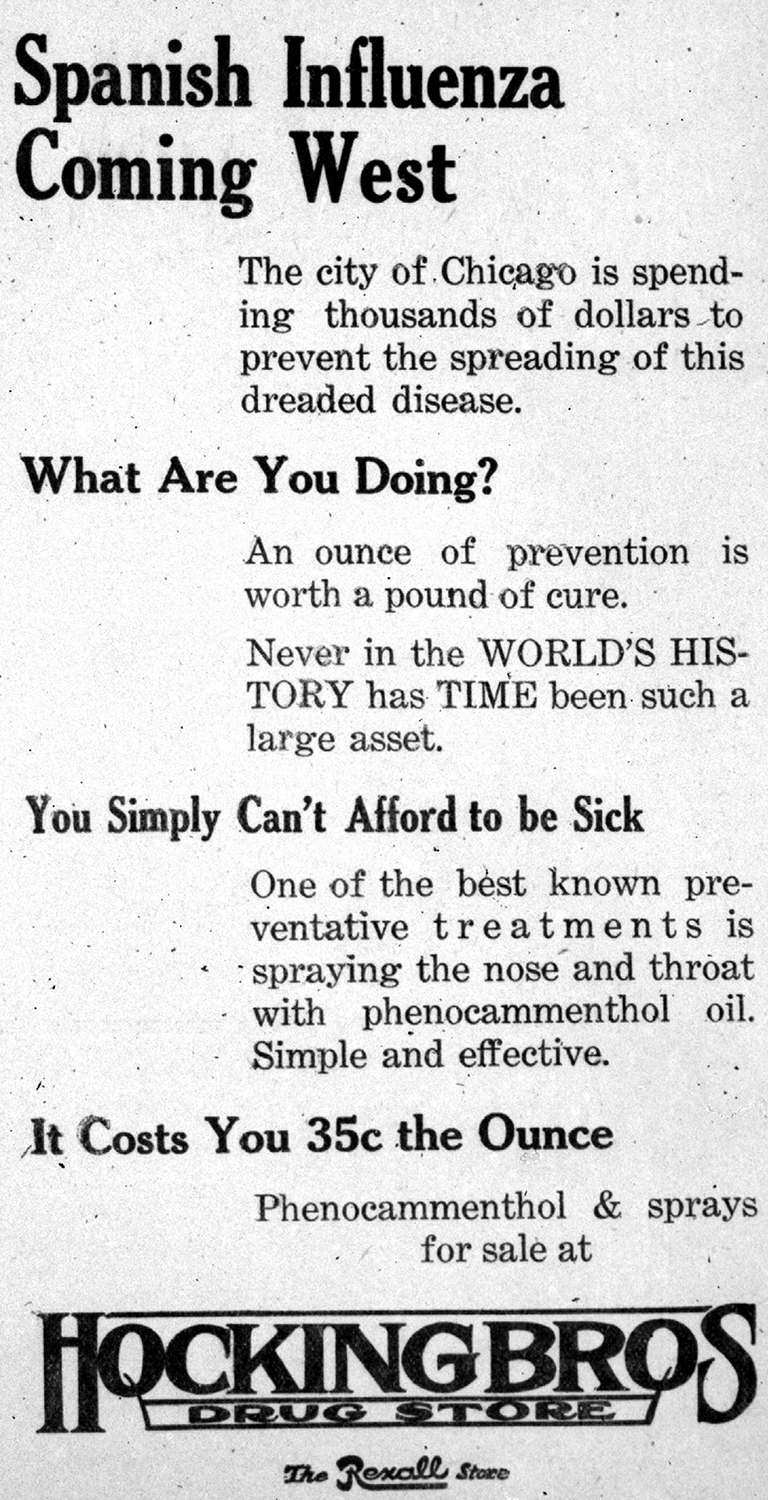

As a result, many Wisconsinites turned to folk cures and patent medicines, hoping to find something to protect them from the flu. A favorite folk cure involved tying a piece of camphor to a ribbon and wearing it around one’s neck, or sewing it inside a shirt so it rested against the chest.

Authorities also recommended a variety of simple mouthwashes and gargles composed of various mixtures of household chemicals, salts, and water. Pharmacists and purveyors of patent medicines took advantage of the public’s fear to sell a pharmacopoeia of pills, tonics, cough medicines, and gargles to hopeful buyers. Drugstores advertised “Influenza Preventative Tablets” and touted atomizers dispensing phenocammenthol as a “wonderful help to prevent influenza.”

Newly created Vicks Vapo-Rub ran quarter-page story-ads in Wisconsin newspapers with headlines like “Spanish Influenza — What It Is and How It Should Be Treated,” and “How to Use Vick’s Vaporub in Treating Spanish Influenza.”

Even Rexall’s Cherry Bark Cough Syrup and Hill’s Cascara Quinine Bromide claimed to be flu remedies.

Perhaps not surprisingly, many state residents turned to alcohol in all its various potent forms. Unfortunately, no amount of wishful thinking, lotions, potions, or liquor could prevent or cure the Spanish flu.

The only real cure for the epidemic was time.

After the second wave of influenza swept through the state in November and December, the numbers of influenza and pneumonia deaths and illnesses gradually returned to normal. But the epidemic had taken a fearsome toll on Wisconsin.

The larger cities suffered the greatest number of the deaths, with 41% of all deaths occurring in the state’s nine largest cities (containing just under one-third of the state’s population). Twenty-three percent of all deaths occurred exclusively in the city of Milwaukee. Virtually all the counties with the highest death totals — Milwaukee, Dane, Rock, Brown, Marathon, Kenosha, Sheboygan, and Racine — had significant urban centers.

Cities with populations under 25,000 (accounting for 22.6% of the population) suffered only 9 percent of the total deaths. Almost one-half of the deaths (49%) occurred in rural towns, villages, and unincorporated areas even though those areas held only 45% of the state’s population. In some rural areas — such as the northern rural counties of Ashland, Forest, Lincoln, Chippewa, and Iron — the death toll ran from one-and-a-half times to double the state average per capita.

While a number of factors affected the death rate, including varying degrees of virulence and a patient’s willingness to remain confined until fully recovered, it seems likely that the distribution reflected the availability of medical care in different communities.

In cities, the large number of victims combined with a shortage of medical personnel resulted in many ill people receiving inadequate care or remaining ignorant about the proper treatment of the disease. In rural areas, the dispersed populations and lack of resources to mount public health campaigns also left many isolated families without assistance.

Small cities probably managed the epidemic most successfully because they had smaller numbers of sick people, less densely packed populations, better ratios of medical personnel to patients, and community infrastructures sufficient to mount volunteer public health efforts that could compensate for the shortage of doctors and nurses.

Everywhere, the flu took a disproportionately high toll on people between the ages of 15 and 40. For example, statistics for Milwaukee reveal clearly that young people died at a rate far greater than the traditional victims of influenza, the very young and the very old. The extraordinary death rate among the youngest and healthiest reflects the unusual nature of the disease.

So long as its victims rested until they thoroughly recovered, death rates remained fairly low. However, if they returned to normal activity prior to a full recovery, they frequently contracted pneumonia and faced a much higher risk of death. Because young, healthy people with strong constitutions often felt well enough to get out of bed before the disease had left their systems, they were more likely to suffer relapses and succumb to pneumonia. Thus robust health and youthful resilience proved a handicap rather than an asset for dealing with the flu.

The untimely deaths of almost 8,500 Wisconsinites, many in the prime of their lives, affected families, communities, and the state in a multitude of ways that extended far beyond the statistical toll. Emotionally, families mourned the loss of beloved children, parents, and relatives. Because the epidemic took such a heavy toll among the state’s young people, it stole the untapped potential of prematurely ended lives.

The loss of breadwinners also brought financial hardship, and even if the breadwinner survived, waiting to fully recover from the flu could result in two weeks of lost pay — an enormous burden for working-class families who lived from paycheck to paycheck. As a result, thousands of families were thrown into poverty and forced to seek charity in the wake of the disease.

The epidemic also cost businesses dearly. Sick workers forced factories and businesses to shorten their hours, curb production, and sometimes close their doors temporarily. Department stores, saloons, poolrooms, dance halls, and movie theaters suffered heavy losses after months of missed profits. For churches funded through weekly collections, the seven-week hiatus surely placed severe strains on their finances. It is impossible to calculate how much agricultural produce spoiled or livestock perished because stricken farmers could not tend their farms.

The epidemic also took a severe toll on the civic life of the state.

All the major centers of community interaction — schools, churches, civic organizations, sports teams, saloons, public meetings — shut down for the duration. Sporting events, parades, and holiday parties were canceled. Combined with a general curtailment of friendly visits, this decline in socializing noticeably weakened the social fabric.

For almost three months, isolation rather than socialization became the norm, leading one newspaper editor to note that the epidemic and resulting bans “isolated families to a degree seldom known in city life,” creating a sense of “forced retirement into oneself.”

The restrictions severely curtailed the public portions of the political campaign of 1918, outlawing the rallies, stump speeches, and parades that characterized elections in normal years. Both the Democratic and Republican parties replaced traditional public campaigning with mail campaigns. Newspapers continued publishing and offered one venue for the candidates, but even so, the races remained low-key and offered relatively little to the newspapers in way of partisan rhetoric or discussions of issues.

The influenza epidemic, combined with the all-consuming interest in the conclusion of the Great War, eroded the democratic process, leading to what one reporter called “the quietest state campaign that has been waged in Wisconsin in years.”

Considering the financial and social costs attached to obeying the influenza restrictions, it is heartening to note that Wisconsinites, on the whole, conscientiously complied with them.

As the epidemic began to subside, the State Board of Health reported a “remarkable fact worth mentioning and one which is greatly to the credit of our citizens,” namely that “practically everyone complied with the closing orders to the best of his ability.” The Milwaukee Health Department had similar plaudits for that city’s residents, stating that among the factors that helped give Milwaukee one of the lowest death rates of all cities of its size was “the readiness of the public to comply with regulatory measures.”

There can be no doubt that compliance spelled the difference between life and death for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Wisconsin citizens.

To attribute such popular cooperation to the supposedly law-abiding nature of residents of the upper Midwest or the simple expression of patriotic duty during wartime fails to explain the response sufficiently, particularly when it is contrasted with that of neighboring Iowans who were certainly no less Midwestern or patriotic.

Iowa officials complained bitterly about the lack of cooperation by the public with their influenza campaign and the intensity of public opposition. Dr. G. H. Sumner, secretary of Iowa’s state board of health, openly lamented the behavior of his fellow Iowans, noting, “It is remarkable how zealous the public will be demanding the most drastic rules and regulations be enforced in case of [a] hog cholera scare, and yet when an epidemic is raging which is jeopardizing the lives of whole communities, many of the same people will manifest the utmost indifference.”

Part of the popular support for the campaigns can be attributed to the existence and nature of Wisconsin’s public health infrastructure and its localized public health network. The legislature’s remarkable foresight in mandating local boards of health provided the manpower and local leadership that made the mobilization such a success.

Without the existence of a legion of local health officers, it would have been impossible for the State Board of Health to have launched a campaign so quickly, enforced its regulations so widely, or organized such extensive local volunteer efforts. The hundreds of locally appointed health officers were familiar with local leaders and community resources, and many had done battle earlier with contagious diseases. They were thus able to organize effective community-based responses at the grassroots level. Whether they merely enforced the closing order or mobilized citizens for volunteer action, the health officers made the anti-influenza campaign a reality statewide.

Furthermore, the success of state and local health officials in controlling earlier outbreaks of other deadly diseases had earned these individuals a reputation for effectiveness that conferred greater credibility on their anti-influenza efforts. This was particularly true of the Milwaukee Health Department, which had battled disease and unsanitary conditions successfully and was widely supported by the business community, politicians, and the general public. To a greater degree than many other states, Wisconsin enjoyed the advantage of a supportive and knowledgeable populace — particularly in its major city.

Combined with the advantages of a strong health network and public support were the additional benefits of wartime mobilization. The war effort certainly drew attention to the campaign, while defense-related organizations provided a source of volunteers. Likewise, the wartime demand for personal sacrifice and cooperation carried over into compliance with public health edicts and aiding the sick. Fighting influenza became as important a patriotic duty as cursing the Kaiser.

Today, the devastation wrought by the flu pandemic in Wisconsin remains shocking, but the passage of time — and the benefit of more than 100 years of scientific and medical progress — make the conditions of 1918 seem comfortably distant. Even the dire firsthand accounts of a dwindling number of flu survivors seem to describe a world more alien than familiar — a world in which viruses were unknown and aspirin was considered quackery. By comparison, the prowess of modern science and medicine to battle disease certainly seems formidable.

Today, the electron microscope allows us to view the tiniest virus; chemistry has unleashed a powerful battery of drugs and treatments; vaccines have virtually eliminated such past scourges as rubella and polio; and genetic engineering seems poised to tackle human illness at the level of DNA. Moreover, the enormous persuasive power of modern media — radio, television, film and the internet — make the placards and handbills that constituted the education campaign of Dr. Cornelius Harper and Dr. George Ruhland seem quaint by comparison.

However, a faith in science and technology to protect us from a global pandemic like that of 1918 is sadly misplaced. Despite its progress and undoubted power to cure, science remains impotent to stop or eliminate many contagious diseases. Viruses are living organisms that constantly reproduce and mutate, developing new strains and gaining resistance to vaccines or drugs. The persistence of diseases such as gonorrhea, syphilis, AIDS and the Ebola virus; outbreaks of once-vanquished plagues such as tuberculosis; and threats such as New York City’s outbreak of West Nile encephalitis — all make the continuing threat much too real.

Every time a new virus emerges, there is the potential that the disease will overcome the combined defenses of human immunity, public health education, and disease research. As the Nobel Prize-winning scientist Dr. Joshua Lederberg has noted, “We live in evolutionary competition with microbes. There is no guarantee that we will win.”

The question is not whether we will ever again face a medical crisis like that of 1918, but how we as a society will respond when it occurs.

It is unlikely in that event that even Wisconsin would enjoy many of the advantages it had in 1918, particularly the support of a population mobilized with a wartime fervor. Nevertheless, it remains a matter of choice whether we work to maintain a well-informed public and a grassroots public health infrastructure capable of meeting such a crisis.

It is well to remember that in 1918, millions sacrificed their individual wishes for the general welfare, and tens of thousands risked infection and possible death trying to alleviate the suffering of others. It was just such a popular impulse that helped reduce the destruction of the epidemic, and which would be equally important for combating a modern-day pandemic. In an age of apathy, cynicism, and individualism, it is worth reflecting long and hard that voluntarism, public cooperation, and an activist government prevented the worst public health calamity in modern Wisconsin history from being much, much worse.

Steven B. Burg is a professor of history and chair of the History and Philosophy at Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania. He received his B.A. from Colgate University and his M.A. and Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. From 1994 through 1999, he worked as a researcher in the Division of Public History in the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us