The Underappreciated Role Of Women Entrepreneurs In The Economy

Communities may be underutilizing a valuable resource for economic growth: women entrepreneurs.

October 26, 2016

We're Open window sign

Communities may be underutilizing a valuable resource for economic growth: women entrepreneurs. The surge of women launching their own companies in recent decades has generated significant job growth and reshaped the gender composition of business ownership in the United States.

From 1997 to 2012, the number of women-owned companies increased by 82 percent, analysis of the U.S. Census Bureau’s Survey of Business Owners firm-level data shows, remarkable growth considering the number of all businesses increased by just 33 percent. Over the decade preceding the Great Recession, privately held women-owned firms added nearly half a million jobs to the economy while male- and mixed gender-owned firms lost jobs. The growth and performance of women-owned firms, particularly when businesses in general were struggling, are evidence of their emerging economic significance.

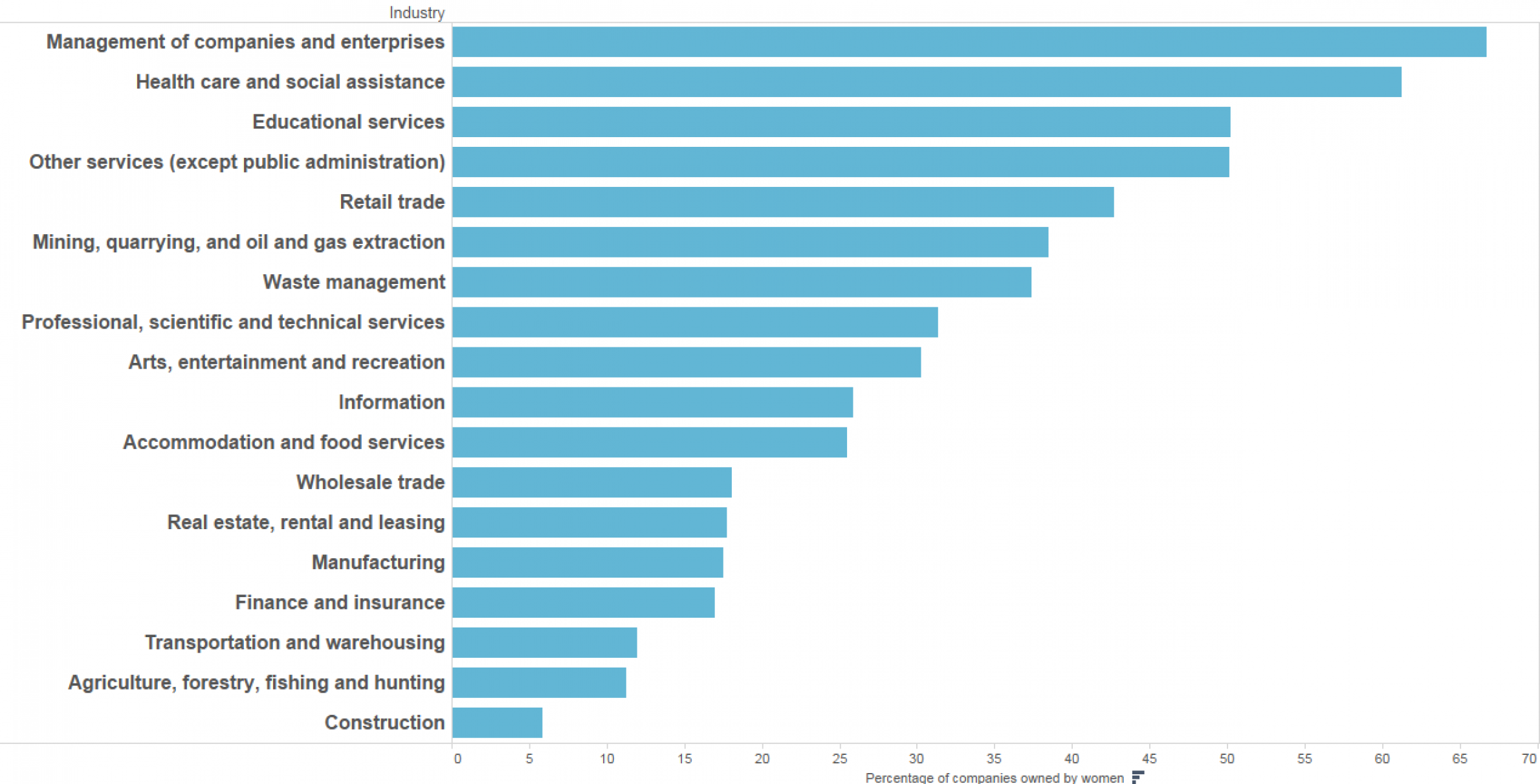

Yet even with this recent growth, women are still a minority of business owners. Based on the Census Bureau’s latest data, women owned 36 percent of all firms. It’s a small share given that women now make up roughly half of the labor force, meet if not exceed men in educational attainment and, in many ways, lead professional lives parallel to their male peers in terms of industry of employment, earnings, promotion, work hours, and so on.

Perhaps more disconcerting, though, is the performance gap between male- and female-owned firms. The Census data show a typical woman-owned firm earned 23 cents in sales for every dollar the typical male-owned firm earned, a differential that is more than three times the oft-publicized gender wage gap.

The lower rate of business ownership combined with their comparatively low sales performance suggests that even though women-owned business is growing, there are still disparities that have yet to be addressed.

The focus of ongoing research is to better understand how women entrepreneurs differ from their male counterparts, the factors driving their self-employment and start-up activity, and the effect their businesses have on the economy. These investigations have found, albeit not surprisingly, that women entrepreneurs differ from men entrepreneurs in important ways. This work shows that even in places where the male and female populations are demographically the same in terms of characteristics like wealth and education, their behaviors, such as employment choices and processes of business formation, are sufficiently different to generate a wide gap in business ownership rates.

The research is analyzing the forces driving job creation by women-owned firms. Recent results indicate that women-owned businesses generated more employment growth than male-owned businesses during the years leading up the Great Recession (2000-2007). In fact, even simple statistics show that without women-owned businesses, job creation in the private sector would have been negative for the decade leading up to the recession. The research findings further suggest that women entrepreneurs’ innovative qualities as pioneers and identifiers of new markets are key to job creation.

Because few others have come before them, today’s women entrepreneurs innovate as they forge their way into the business community and become valuable role models to those who follow. Moreover, by forming new professional connections, women overcome information barriers often perceived as “good old boys” networks. Such foundational networks can be important when seeking information about suppliers, feasible financing and consumer demand that is critical to the success of businesses.

Women practice different management strategies and they develop new products, processes and services, operating in previously unrecognized niches of the market. Their innovations, all of which generate valuable market information, can lead to new jobs. For example, women have been innovators in children’s entertainment with products such as Baby Einstein and Build-a-Bear. These comparative advantages may be especially pertinent in high-growth industries such as health care and education where large numbers of women own businesses.

Along with being an important source of job creation, women-owned businesses are an important source of economic stability. Previous work has shown that women business owners are less likely to lay off employees during an economic downturn and further analysis of uniquely detailed data suggests this management practice has broader benefits across regional economies. Controlling for other economic factors, counties in a state like Florida where a relatively large share of businesses are women owned (38.5 percent) had more stable employment and income during the Great Recession, compared to counties in Wisconsin where the share of female-owned business is below the national average at 31 percent. These results are consistent with women business owners not only retaining employees, but also maintaining their hours and/or wages, therefore resulting in more stable overall earnings.

Given the job creating capacity and stabilizing influence of women entrepreneurs, understanding their motivations is critical to realizing their full innovative potential. Additional research suggests that women often use self-employment to accommodate the demands of raising children. Compared with wage-and-salary employment, with its modest leave policies and demanding schedules, the flexibility of self-employment may make it attractive to women with children. As evidence of this preference for flexibility, self-employed women generally provide more of their own child care, even while working. Adequate child care availability could foster high-growth female entrepreneurship by reframing self-employment opportunities, alleviating time constraints and allowing a focus on building businesses.

Taken together, these studies of women entrepreneurs imply that policy geared toward equitably enhancing entrepreneurship will need to account for gender differences. Given women entrepreneurs’ economic contributions, implementing policies that do not take full advantage of their job-creation, economic stabilization, product development and management strategies would be a missed opportunity, particularly in high-growth industries such as health care and education. Communities that account for women-owned businesses in their economic development strategies stand to improve opportunities for women entrepreneurs and in turn enhance the long-term stability and growth of their local economies.

Tessa Conroy is an economic development specialist at University of Wisconsin-Extension Center for Community and Economic Development and an assistant professor at UW-Madison. She is conducting her research on women entrepreneurs with UW economist Steven Deller and Colorado State University economist Stephan Weiler.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us