The rape kit backlog and Wisconsin's 2025 Supreme Court race

Wisconsin's backlog of testing sexual assault evidence in the 2010s is at issue in the 2025 race for state Supreme Court as Susan Crawford attacks Brad Schimel's record as the state attorney general.

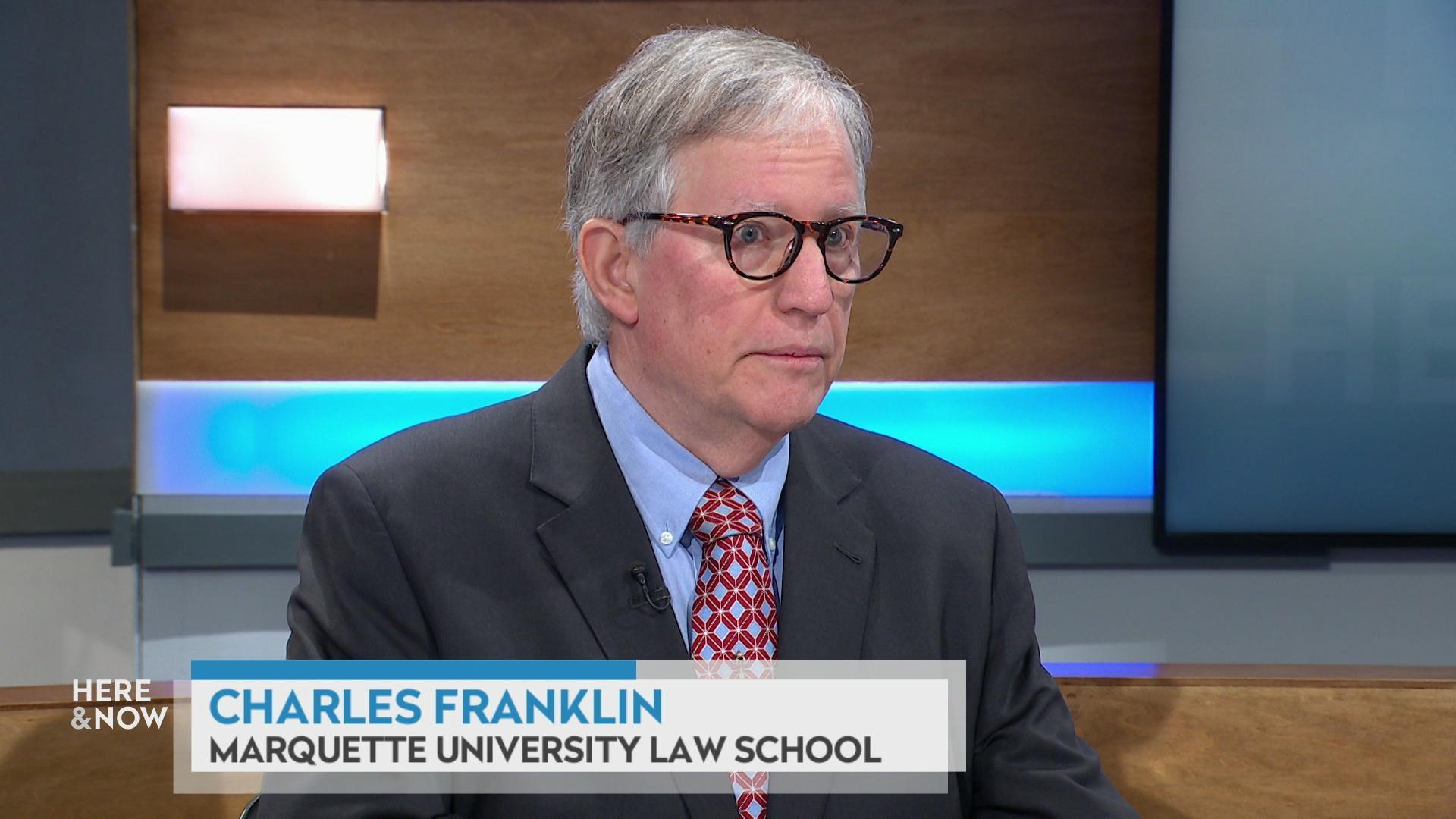

By Zac Schultz | Here & Now

March 20, 2025

Early voting is underway in the spring 2025 election for a seat on the Wisconsin Supreme Court. While many voters are focused on what decisions the winner will make as a member of the court for the next 10 years, liberal candidate Susan Crawford wants voters to focus on decisions made by conservative candidate Brad Schimel about 10 years ago.

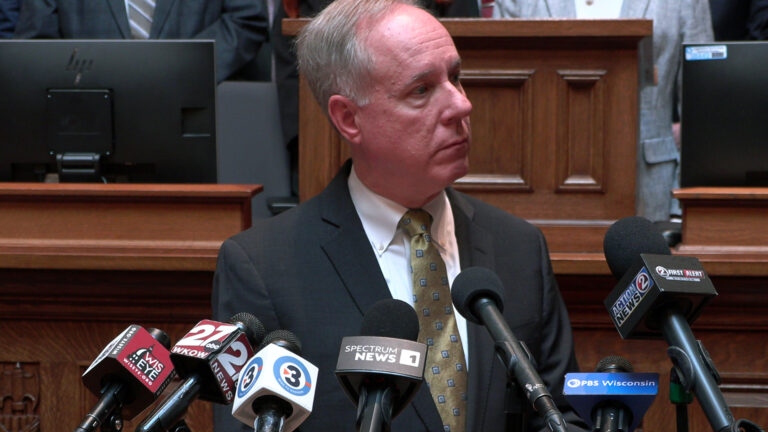

In 2015, Brad Schimel was the newly-elected Republican attorney general of Wisconsin.

As he came into office, Wisconsin was still counting how many untested sexual assault kits were sitting on evidence shelves in police stations and hospitals around the state, some of them decades old. Eventually the tally reached more than 6,800.

“We’ve been very instrumental in sounding the alarm on this issue,” said Ilse Knecht, the policy director for the End the Backlog Initiative, a national group that was instrumental in pushing states across the country to inventory and test their backlog of sexual assault kits, including in Wisconsin.

“The issue is, once you determine that you have 6,000-plus untested rape kits, what do you do about it? And that is definitely very complex,” Knecht said.

Schimel described the complexity of this process

“We found those survivors. We talked to them. We got their consent to test those kits,” he said. “And before my term of office [ended] as attorney general, we tested over 4,000 kits — every single kit that needed to be tested was done in that four years.”

Crawford’s campaign is challenging Schimel’s record on the issue in her campaign.

“Brad Schimel let thousands of rape kits go untested for years … while rapists walked free and victims waited for justice,” say the current and then a former Dane County Sheriff in one campaign ad.

As a Wisconsin Supreme Court candidate, Schimel stands by his work as attorney general.

“I’m proud of the work — what we accomplished for survivors of sexual violence,” he said.

Crawford, his opponent, said Schimel shouldn’t be so proud.

“He only put his foot on the gas when it became an issue in his reelection campaign,” said Crawford. “So, again, this is Brad Schimel’s partisanship. His political future was at stake and he was worried about it. So he started working on that backlog and made some progress in it. But voters saw through it and they sent him home.”

The key question is whether Schimel showed enough urgency on this issue.

Crawford said staffers in the Wisconsin Department of Justice told Schimel about the backlog and asked him to get the Republican-controlled state Legislature to secure the resources needed to test the kits.

“He pushed back and said go look for a cheaper way to do this, look maybe for some grant funding,” she said.

Schimel spoke to the funding of this work.

“We also recognize we couldn’t just take 6,000 kits and dump them on the crime lab — they have day-to-day responsibilities,” he said. “So we had to go forward and secure funding to be able to pay for getting those kits tested.”

Eventually the state secured more than $6 million in federal grants to process the backlog and send the tests to private labs.

Schimel announced the backlog was cleared just a couple months before he was up for reelection in 2018. He lost in that election, and the backlog delays were a big part of the ad campaign against him — just as they are in 2025.

“Over two years, Brad Schimel tested only nine rape kits out of 6,000 that needed testing, while rapists walked free and victims waited for justice,” intones the narrator in another Crawford campaign ad.

Knecht said these concerns were not just partisan attacks, as the End the Backlog Initiative had the same questions.

“We kept sort of asking what is going on? Why is it taking so long? There were years when very, very few — I think it was even less than 10 kits were tested,” Knecht said. “So we were engaging with folks in the state trying to find out exactly what was happening. But it was a big concern in our office — what is going on in Wisconsin?”

Crawford said the state budget in 2015 provided new positions that Schimel requested, but they just weren’t for the crime lab.

“He was going to the Legislature asking for a new unit of attorneys called the solicitor general’s office that he then utilized for the entire time he was in office to pursue right-wing lawsuits,” Crawford said. “Those were Brad Schimel’s priorities instead of addressing this backlog of sexual assault kits.”

Knecht said she has seen these kits get expedited elsewhere.

“It really does come down to where your priorities are,” she said. “If this is a priority for a governor and attorney general. I have seen them move mountains to get this done and to get it done relatively quickly.”

Schimel said he won’t let attacks over the backlog go unanswered.

“Frankly, we’re ready for it — and we’ve got sheriffs that have come forward to talk about this very issue,” he said.

One Schimel campaign ad features the Dodge County Sheriff.

“I was there when Brad Schimel initiated the sexual assault kit initiative, pushing hard to make sure victims of sexual assault were able to see their offenders convicted, to make sure there was justice,” the sheriff says.

Schimel said the people that worked on this issue with him agree he took the backlog seriously.

“Check with groups like the Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault,” he said.

“Here & Now” asked the Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault for comment, and they declined to weigh in, citing the “highly partisan” nature of this nonpartisan election.

After the backlogged rape kits were tested, sexual assault charges, guilty pleas and convictions soon followed, including in Portage County, Waupaca County and Brown County in 2019, Oneida County in 2020, Milwaukee County in 2021, Dane County in 2022 and Kenosha County in 2023.

“This is a justice issue. I mean — I will just say, overall, the rape kit backlog exists because of a failure of the criminal justice system as a whole to take sexual assault seriously and to prioritize the testing of rape kits,” said Knecht.

“He got nine kits tested in a period of two years. And, you know, justice delayed is justice denied,” said Crawford.

“We worked a miracle,” said Schimel. “And it’s a scam to suggest to voters that this was anything other than that.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us