The Allure Of Destination Breweries As Rural Economic Engines

Craft beer fans seeking different flavors are accustomed to hitting the road to taste offerings from breweries both near and far from home.

August 25, 2018

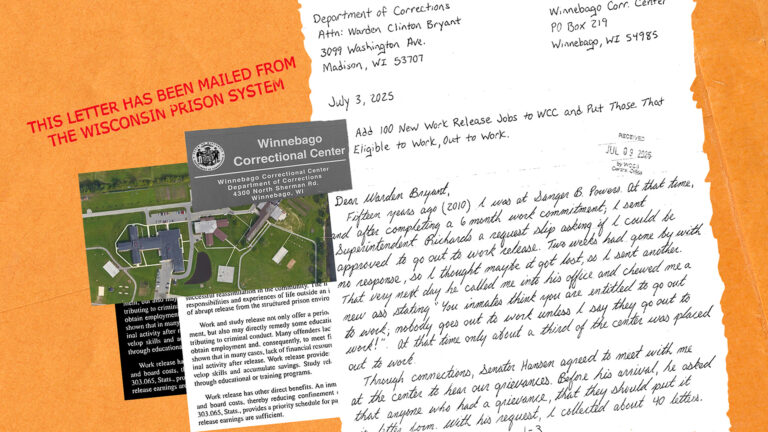

Driftless Brewing patrons gather outside old brewhouse

Craft beer fans seeking different flavors are accustomed to hitting the road to taste offerings from breweries both near and far from home. Special releases of new and limited-run creations are a big draw, but so too are the breweries themselves.

As the craft beer industry has blossomed over the past decade, so too have options for such visits. The Brewers Association, a national trade association for craft beer-related businesses, reported that in 2017, craft consumers visited three-and-a-half breweries near their homes and two-and-a-half breweries within two hours’ driving distance on average.

“Beer tourism” is one label for the phenomenon of people planning getaways around visiting craft breweries, as is the punchier “beercation.” In 2016, Travelocity established a “beer tourism index,” which identified the top destinations for craft beer in the United States. (Madison was ranked ninth among large metro areas.)

Growing in size and popularity, these “destination breweries” often boast taprooms, restaurants, outdoor spaces and other attractions. Some breweries are even building hotels to attract visitors.

“We’ve seen people’s desire to visit breweries go up a lot in recent years,” said Bart Watson, chief economist at the Brewers Association. “There’s been a real demand shift in beer. People want fuller flavor and variety, and they want to support small and local breweries.”

Watson noted that this phenomenon is not unique to the beer industry, and that consumers are also increasingly willing to travel to wineries and distilleries, too.

While the recent explosion of craft beer has found many new operations clustered in cities, several of Wisconsin’s prominent destination breweries are located in more rural areas.

Rural destination breweries

Two high-profile craft beer destinations in Wisconsin are New Glarus Brewing and Central Waters Brewing. Based in the villages of New Glarus and Amherst, respectively, communities in rural settings yet not too far a drive from larger cities, both have been drawing increasingly large crowds for the past couple decades. Newer operations around the state are trying to follow in their footsteps.

Driftless Brewing Company has high hopes to build a reputation as a craft beer destination. Established in 2014, it initially operated a one-barrel brewing system out of a former grocery store in Soldiers Grove, a village in Crawford County. It sold their beer out of a makeshift taproom and a few local businesses. But the brewery is set to grow considerably with a $1.2 million expansion to a 15-barrel system and 49-seat tasting room in the works, funded by private investors, bank and business development loans, and a grant from the Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation.

The brewery already drew attention from nearby residents and visitors to its corner of the state. But after the expansion, which is slated for completion in 2019, its owners and staff are hoping to spread word of their beers much wider.

“Even though we’re in a town of less than 600 people, we’re going to succeed in having a bigger brewery to get us out into Wisconsin on a larger basis,” said Cynthia Olmstead, business and operations director at Driftless Brewing.

“We’d like to fulfill demand from La Crosse to Milwaukee, and to bring people into town through the taproom. We’ll be bringing a huge amount of people into Soldiers Grove, and that’s really exciting,” she said.

Driftless Brewing has built close connections with others in the Soldiers Grove community who support its efforts to expand, and in turn, build the local economy.

“We always try doing and looking and promoting business in our area. And we’ll help you get started so we can create businesses in a small town. Well, small towns are losing that,” said Soldiers Grove village president Steve George in an interview with Wisconsin Public Television.

Olmstead noted how she’s already seen positive impacts that the brewery has had in the community. Residents are “beyond thrilled to have a small taproom in their tiny town,” she said. And visitors are “thrilled to come and support a brewery steeped in values of good environmental practices that uses Wisconsin ingredients,” she added.

Olmstead said she’s also seen motorcycle groups, car clubs and other groups visit Soldiers Grove just to stop by Driftless Brewing, which gets visitors from Chicago, Minneapolis, Iowa City and elsewhere around the Midwest.

When visitors check out the brewery, Olmstead said they also may take a look at other local businesses, creating economic ripples throughout the small town.

That effect could eventually help attract other entrepreneurs to Soldiers Grove, said Jim Bowman, executive director of Driftless Development Inc., a local economic development organization that assisted the brewery in funding its expansion. In coordination with the University of Wisconsin-Extension, Driftless Development is completing a market study to determine the goods and services are needed in the area.

“We continue to promote and have a relationship” with Driftless Brewing, said Bowman. “Our next job is to find other complementary businesses near them and highlight them as a business expansion.”

Brewing broader goals

The economic impact of destination breweries can extend well beyond their home communities.

One effect is related to building regional supply chains. Craft breweries increasingly aim to use locally sourced ingredients from around the state in their beers. Driftless Brewing uses 95 percent local or regional ingredients, sourcing most of their hops and malt from inside Wisconsin, as well as fruit, honey and other ingredients for seasonal beers.

“Sometimes we just pick the fruit ourselves,” said the brewery’s business director Cynthia Olmstead. “Being local is part of our brand now.”

Brewers Association economist Bart Watson also noted that locally owned breweries add value to their state’s economy, through adding jobs, paying property taxes, and buying locally on the supply chain.

The growth of Driftless Brewing reflects national trends in the craft beer industry.

Starting with the emergence of the homebrewing movement in the late 1970s, followed by a few decades of incremental growth by startup businesses once called “microbreweries,” the craft beer movement took off across the U.S. as the 2010s opened. As of 2017, reports the Brewers Association, Wisconsin had 160 craft breweries — up from 73 in 2011 — which yielded over $2 million in total economic impact in the previous year.

That trend of growth means more competition, but it also makes for more places craft beer fans can visit.

Along with Driftless Brewing, other craft beer destinations in southwestern Wisconsin, business with both deep local roots and gleaming new facilities, are attracting visitors. Potosi Brewery and the adjoining National Brewery Museum in Potosi, was launched in 2007 and expanded in 2015, though the brand goes back almost to the state’s founding. Meanwhile, Vintage Brewing, founded as a brewpub in Madison, opened a large flagship facility in Sauk City in early 2018.

“Craft brewing is creating its own economy,” said Olmstead. “Whether it’s renovating a neighborhood in an urban area, or places like us that haven’t had a whole lot of economic development.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated with additional information about Driftless Brewing’s expansion, as well as with a video segment from the Wisconsin Public Television documentary Portraits From Rural Wisconsin.

Kristian Knutsen contributed to this report.

Julie Grace was an intern with WisContext in the summer of 2018 and worked with Wisconsin Public Television through the O’Brien Fellowship in Public Service Journalism at Marquette University.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us