Tech industry job tremors and AI boom propel changes at Wisconsin's colleges

Multiple Universities of Wisconsin campuses are expanding computer science and artificial intelligence offerings for students, even as graduates enter an increasingly uncertain job market in the wake of the tech industry's pandemic and AI booms.

By Elijah Pines

August 7, 2025

A sign marks an entrance to the Computer Sciences and Statistics Building on the UW-Madison campus on July 9, 2025. The university's School of Computer, Data & Information Sciences is scheduled to move into a new building named Morgridge Hall for the fall 2025 semester. (Credit: Elijah Pines / PBS Wisconsin)

When Bill Zhu started a computer science major at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2021, he had no expectation the tech job market would dip, or would dip so soon. Over the previous decade, computer science became one of the most popular majors for new college students.

In 2011, UW-Madison had about 200 computer science students. By its spring 2025 semester, the university had 3,372 students enrolled as computer science majors. In the same year Zhu enrolled, UW-Madison announced plans to build a $225 million academic building for its new School of Computer, Data and Information Sciences to accommodate the fast-growing major. The school aims to help foster tech businesses in Wisconsin by producing innovative research and training talent. After four years and an additional $42 million in costs, the new building is set to open in the fall 2025 semester.

These computer science enrollment trends followed a booming information technology industry, which added 2.3 million jobs between 2010 and 2020, according to CompTIA, a tech trade association. By the start of the 2020s, expectations for tech industry growth remained high. A 2022 report by the National Science Foundation projected 7% growth over the following 10 years in science and tech related fields, much higher than growth in other types of jobs, which was predicted to be 2%. Moreover, the largest share of that 7% growth comes from occupations that require bachelor’s degrees, like computer science.

Though expectations for tech may have been glowingly positive, a hiring spurt during the COVID-19 pandemic has reversed. Mass layoffs proceeded at multiple major tech companies and layoffs continued over the next couple years — trueup.io estimates that 430,000 employees were let go in 2023 alone.

“When I first joined in, comp sci was probably the easiest tech job to get into,” said Zhu, who graduated from UW-Madison in May 2025 with a computer science degree and a business certificate. “It was like new grads were getting offers with $300,000, people at boot camps are getting hired on the spot. Everyone was going to seat us.”

Zhu observed this lucrative job market when he first enrolled in college in 2021. As his time to enter the workforce approached, Zhu started sending out job applications in the summer before his senior year, which he said was standard for his field. Over the next 11 months, he submitted around 100 applications to different job postings. He didn’t receive a single offer until the week of his graduation.

Despite predictions of a booming market, many recent computer science graduates feel it’s too difficult to find a job in the industry.

“There’s not many people that I know that are thriving in this situation,” Zhu said. “Many of my friends right now are either looking towards a master’s degree so they could stay in school for a bit longer before they have to go out into the job market. Some of them just can’t find jobs, and they’re doing something that isn’t what they are hoping to do, just an odd job here and there.”

When Zhu enrolled at UW-Madison, he and his cohort entered at an unusual time for hiring with the tech industry in the midst of a hiring boom.

“In 2021, you didn’t really have to know a ton of stuff. You could just be a really good Java coder and get snapped up by these tech companies,” said Beth Karabin, a technology, data and analytics career and internship specialist at UW-Madison. As a career advisor, Karabin has seen first hand the anxieties students have with entering the tech market.

Construction equipment surrounds the nearly completed Morgridge Hall, the new home of the UW-Madison School of Computer, Data & Information Science, on July 9, 2025. Over the past 15 years, the number of computer science majors at the university has grown from around 200 to nearly 3,400. (Credit: Elijah Pines / PBS Wisconsin)

Karabin recalled in the early 2020s that many of her students would get internships at big tech companies — often referred to by investors as FAANG or the Magnificent 7 — but in short order these same businesses made mass layoffs. Over the past three years, with layoffs and a job market flooded with mid-career professionals, Zhu said getting an internship was “impossible” during his time in school.

“It’s simply hard to hire people without knowing what’s going to happen in the near future,” Karabin said. “I would say 2024-25 was a little tough for students, because the first thing to get cut often is internships,”

Many of the students who consulted with Karabin felt discouraged by not getting internships with a big tech company, but she insists that mass hirings and layoffs are normal cycles that will eventually even out.

“I guarantee you, people felt exactly the same way in 2001 when the tech bubble burst,” Karabin said, referencing the early 2000s recession. “Careers are sort of meandering things to where, if you don’t get it at the first try, it’s a good idea to keep a rough goal in mind and continue to try to circle that and keep trying to get in until you do manage it.”

AI and long-term impacts on tech

While the past few years of mass hirings and layoffs were an exaggerated version of cycles found in any industry, the early 2020s also saw another massive shift in tech. The large-scale adoption of an array of software and tools labeled as artificial intelligence has become a dominant priority for tech companies, including in terms of their internal practices. Just in the early summer of 2025, Google’s internal learning platform was changed to teach employees how to use AI and Microsoft sent an internal memo pushing staff to use more AI.

A concern for many students, like Zhu, is that AI will “do the job of many newer grad students.” On the other hand, Karabin believes that AI will always need a human to oversee the output of these tools. What is undeniable is the gargantuan demand for an AI-oriented skillset.

“Now even any entry level positions require some amount of AI experience,” said Rahul Gomes, a computer science professor at UW-Eau Claire. “It’s going to create new opportunities. It’s just that to explore or grasp those opportunities, one has to be willing to take on AI, to learn AI to master some specific field of AI.”

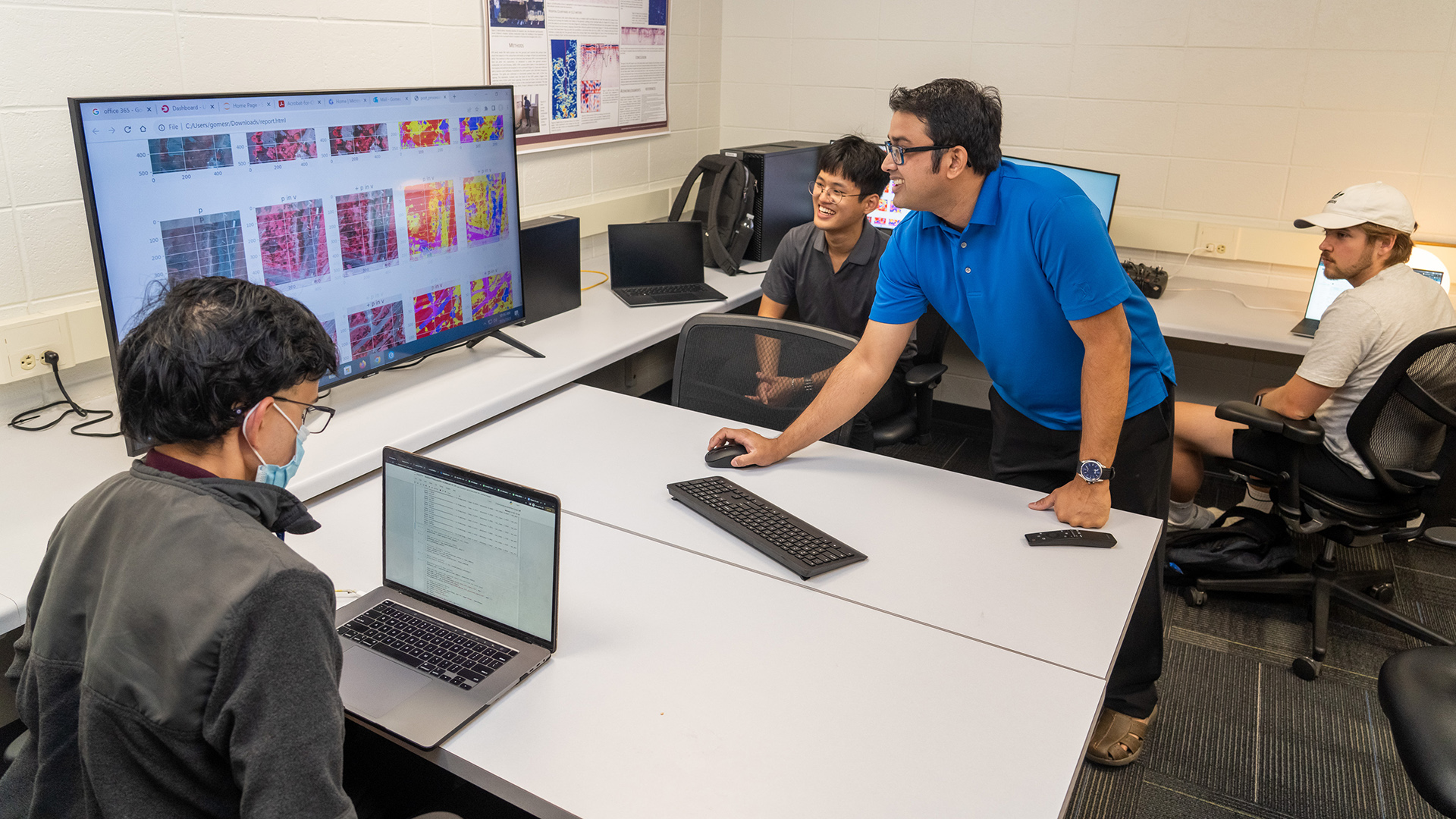

Students work with UW-Eau Claire computer science professor Rahul Gomes in a research lab. (Credit: Courtesy of Shane Opatz / UW-Eau Claire)

Gomes was part of UW-Eau Claire’s task force to create a new AI major. Its curriculum was designed to be obtainable both with or without a computer science background. Gomes believes that there are future specialized jobs focused on applying AI to specific disciplines.

For example, in 2024 students at UW-Eau Claire helped research an AI tool to analyze medical reports for physicians at the MayoClinic. The goal was to help save time in an industry where every minute matters.

“The research aspect has been really helpful, because they’re not only learning to apply a technology, they are learning to apply a technology which will have direct patient health outcomes. That motivates them,” Gomes said.

Karabin explained that the trend at the moment for tech jobs is towards specialized roles. But with all these changes, many students feel doubtful about entering the market as it is. Zhu went as far as telling his college-freshman sister to not study computer science as he thinks the job market will be too competitive.

While it might be a competitive industry at the moment, Karabin doesn’t think opportunities are closed.

“It’s always possible you will get the end goal, and knowing what that end goal is will help you plan the steps in that direction,” Karabin said. “And steps are usually how a career is built.”

Editor’s note: PBS Wisconsin is a service of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us