Snapshot Wisconsin Reveals The Hidden Lives Of Wild Animals

There are other trail camera networks around the U.S., but Snapshot Wisconsin is a unique undertaking.

By Will Cushman

March 22, 2019

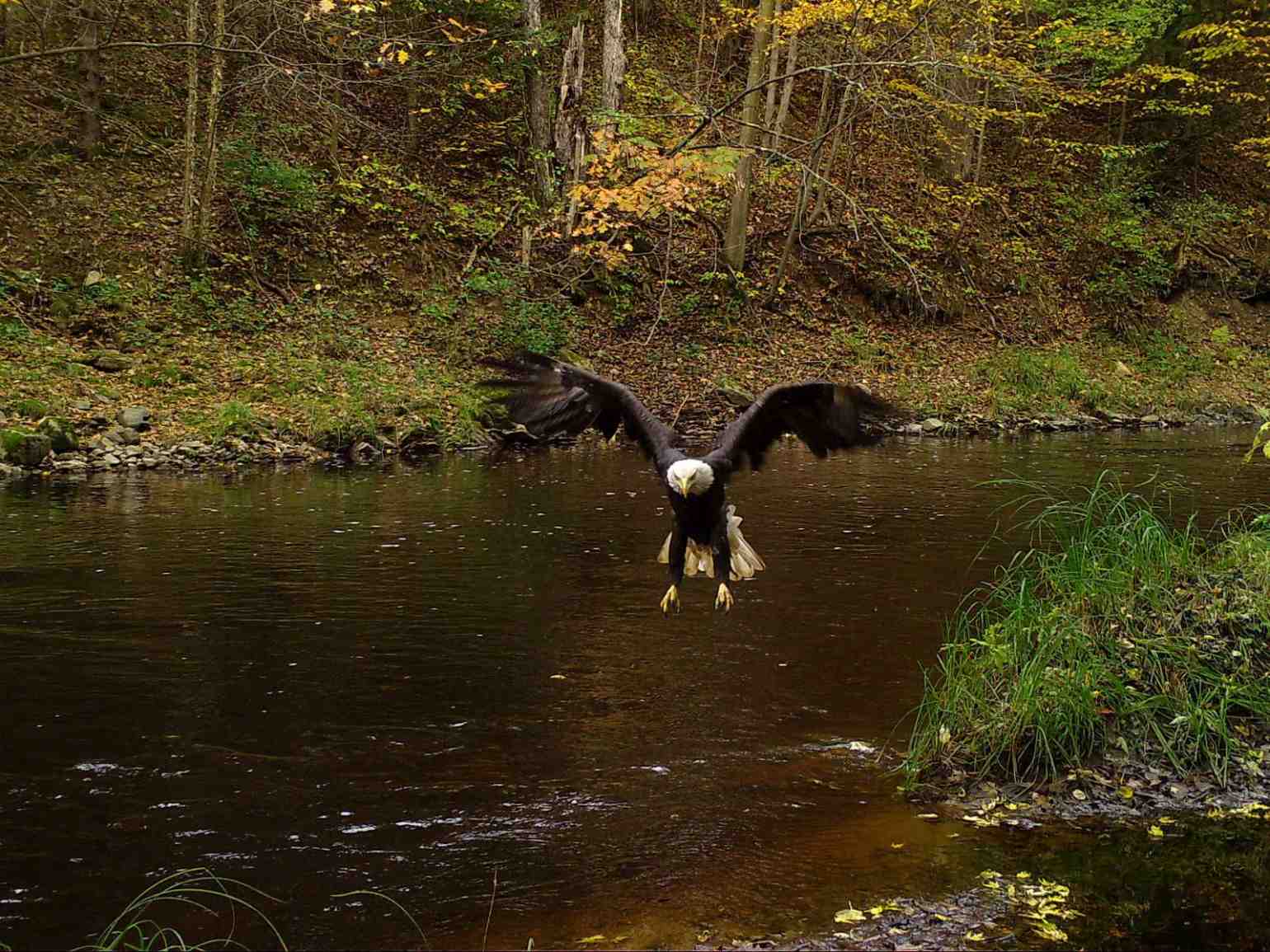

Snapshot Wisconsin photo of bald eagle in Taylor County crop

Instagrammers may be familiar with a type of before-and-after post, known as a “glow up,” wherein people share side-by-side photos of themselves to highlight a physical transformation that makes them proud.

But ‘grammers around Wisconsin who can’t stop scrolling through their feeds might consider a wondrous physical transformation that occurs every springtime — the annual “green up” of the the state’s landscape. These greenings that occur each spring as foliage grows are gaining new attention from researchers and outdoor enthusiasts as a unique network of thousands of remote cameras records Wisconsin’s wild places and wildlife through the seasons.

Launched in April 2016, Snapshot Wisconsin is a project of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. It has two major goals, according to Jennifer Stenglein, a DNR research scientist: to beef up the agency’s wildlife monitoring efforts, and to involve members of the public in those efforts as broadly as possible.

Stenglein described how the project works at a Nov. 16, 2016 lecture for the Wednesday Nite @ the Lab series on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

Snapshot Wisconsin’s roots come from funding provided through a federal excise tax on guns, ammunition and archery equipment. The 11 percent sales tax originated in the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, passed in 1937. Proceeds from the federal tax are divvied up to the states to fund wildlife habitat restoration and research.

The project came into being as Wisconsin received a windfall of new Pittman-Robertson dollars following the election of President Barack Obama, Stenglein said, when gun and ammunition sales skyrocketed. The additional sales, and the additional Pittman-Robertson funding that accompanied them, became known locally as the “Obama bump,” according to Stenglein. Snapshot also received funding via a grant from NASA to support research by scientists at UW-Madison.

There are other trail camera networks around the United States, but Snapshot is unique because it’s administered by a state government agency and depends heavily on volunteers. Among those volunteers are more than 1,500 Wisconsinites who place and monitor trail cameras on private and public land throughout the state. Many thousands more from Wisconsin and around the world volunteer to identify images of wildlife captured by the trail cameras after they are uploaded to Snapshot Wisconsin database on a crowdsourcing research platform called Zooniverse.

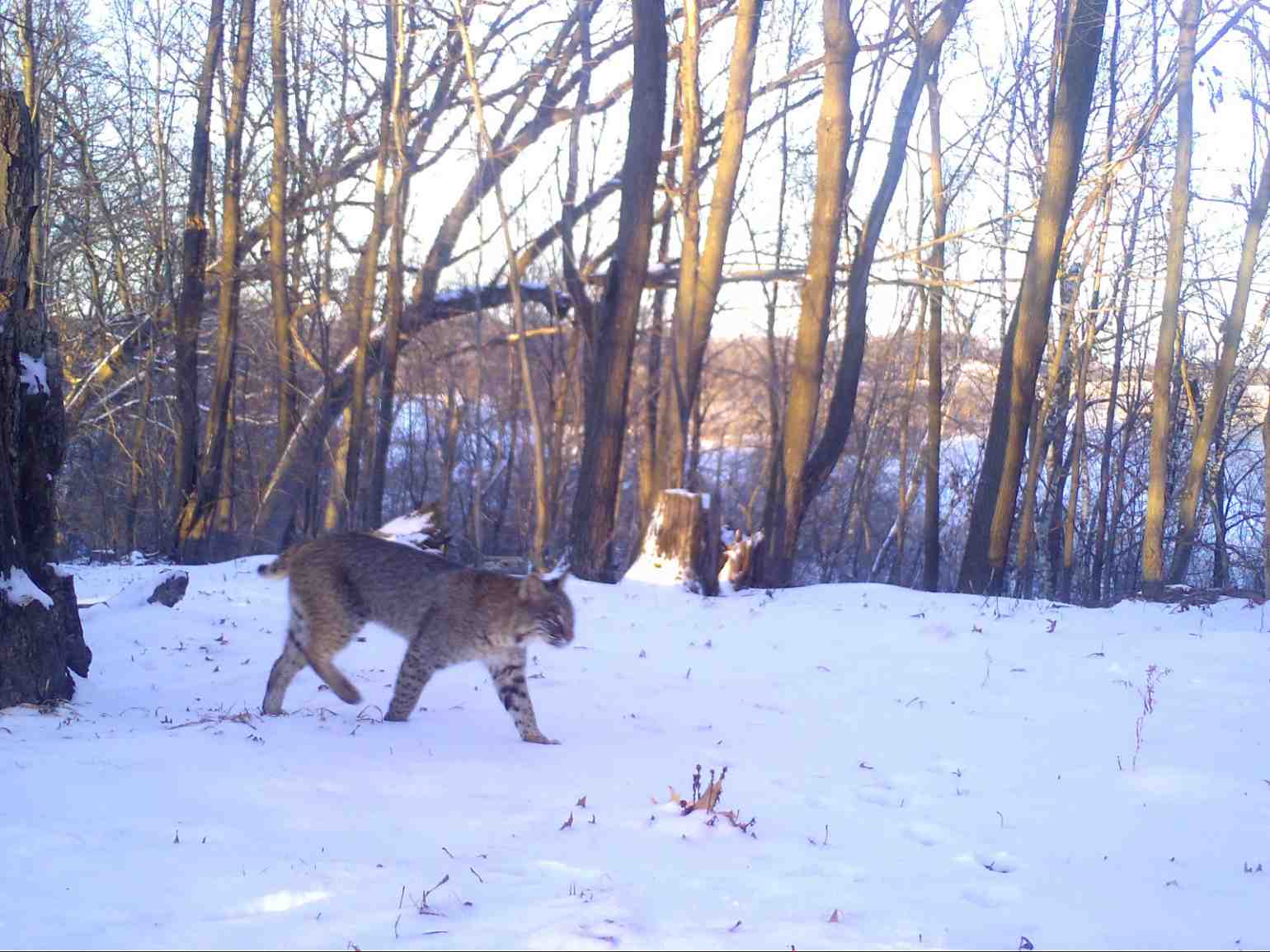

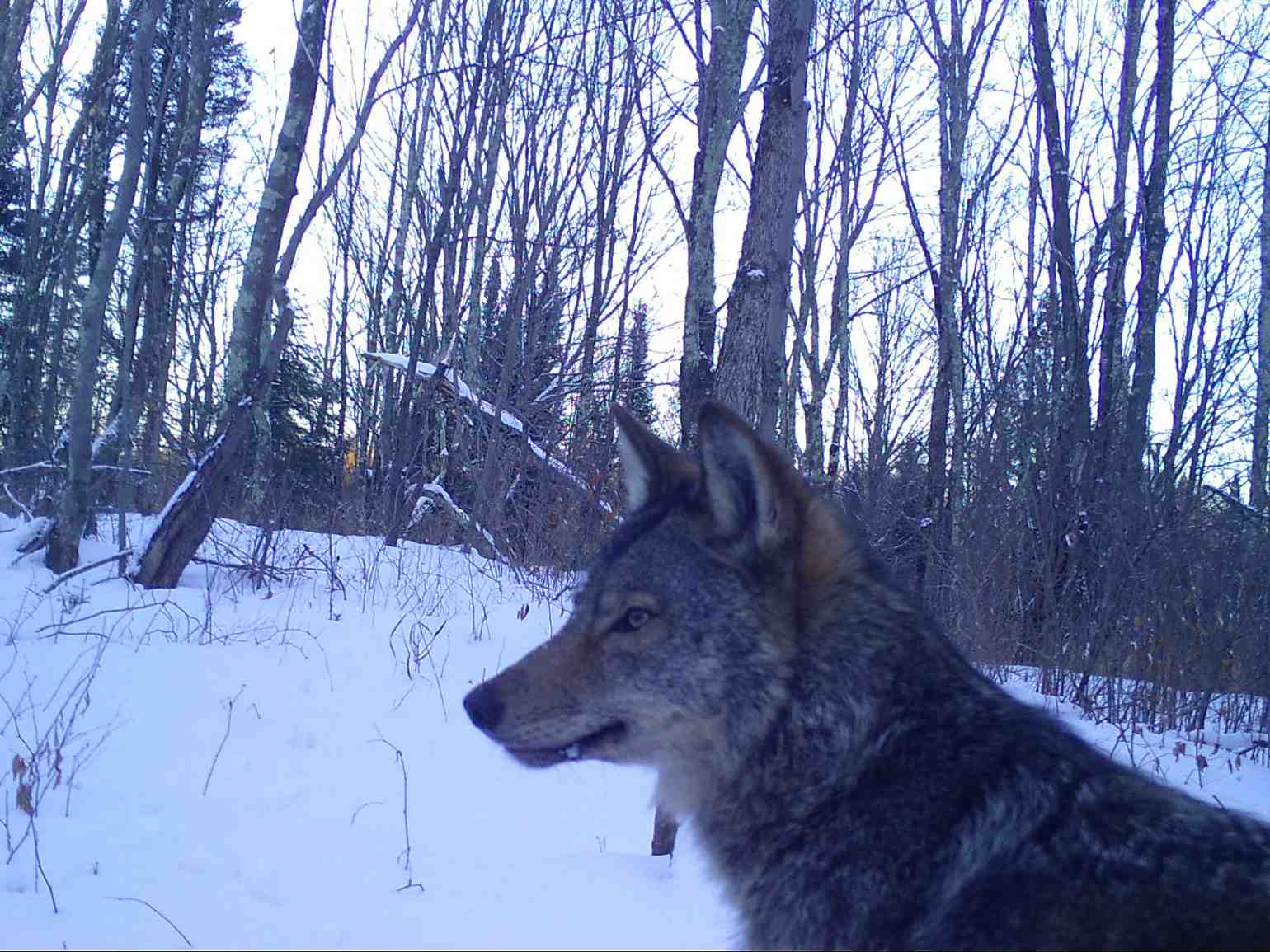

Stenglein said the trail camera network and citizen scientist volunteers are helping the DNR better understand populations of everything from deer to wolves and bobcats to prairie chickens. The information is particularly valuable in the southern two-thirds of the state, she said, where it fills a large gap in wildlife monitoring — the DNR has historically focused its on-the-ground monitoring in the state’s wilder northern regions.

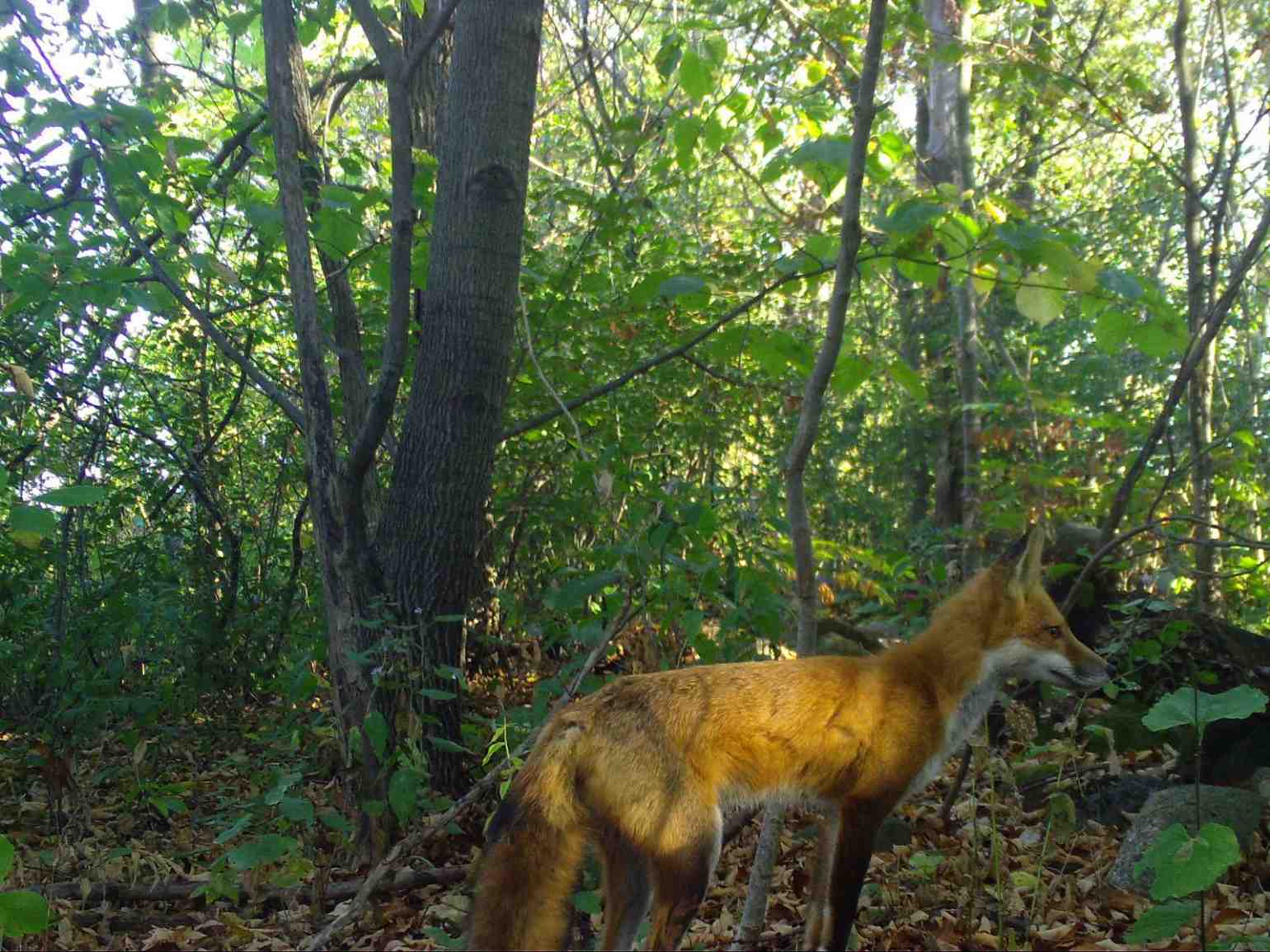

Trail cameras have long been a popular way for hunters and outdoor enthusiasts to track wildlife. Most, including those the DNR uses, employ sensitive motion detectors that trigger a quick burst of photos whenever something moves inside their field of view. The cameras also use unobtrusive infrared light to capture nighttime images of Wisconsin’s nocturnal creatures.

“What this [program] gets at is a way to monitor all types of wildlife,” Stenglein said.

But the DNR is interested in more than simply monitoring wildlife. The agency is beginning to use the data collected and confirmed by volunteers to make wildlife management decisions.

In a March 2019 interview, Stenglein told WisContext the trail cameras are proving useful in helping the state plan for deer hunting season by supplementing on-the-ground surveys of fawn-to-doe ratios. This annual summertime estimation helps the DNR understand roughly how many fawns have survived their first few months, when mortality is highest.

“Snapshot’s been able to fill in gaps when there aren’t as many observers in an area,” Stenglein said. “All that information is one of the inputs in the population models, [and] that information is being used right now in the state as the deer advisory council is discussing the upcoming hunting season.”

The trail cameras assist other on-the-ground monitoring efforts as well, including the agency’s annual winter tracking of wolves and a new program that will closely monitor the state’s only greater prairie chicken mating grounds — technically called “lekking” grounds — near Stevens Point.

Even the images that don’t include confirmed wildlife — about 85 percent of them — are of interest to researchers who want to better understand how seasonal vegetation cycles affect wildlife.

To that end, all of the Snapshot trail cameras are programmed to take a photo in unison late every morning, just as NASA’s MODIS satellite cruises high above Wisconsin. The satellite tracks a number of environmental metrics, including cloud cover and photosynthesis activity. By taking on-the-ground photos just as MODIS captures images from high above, the Snapshot network can provide higher-resolution data related to green up. Researchers, including UW-Madison forest ecologist Phil Townsend, can then analyze the combined data to try to understand the interplay between wildlife and their living — and changing — environments.

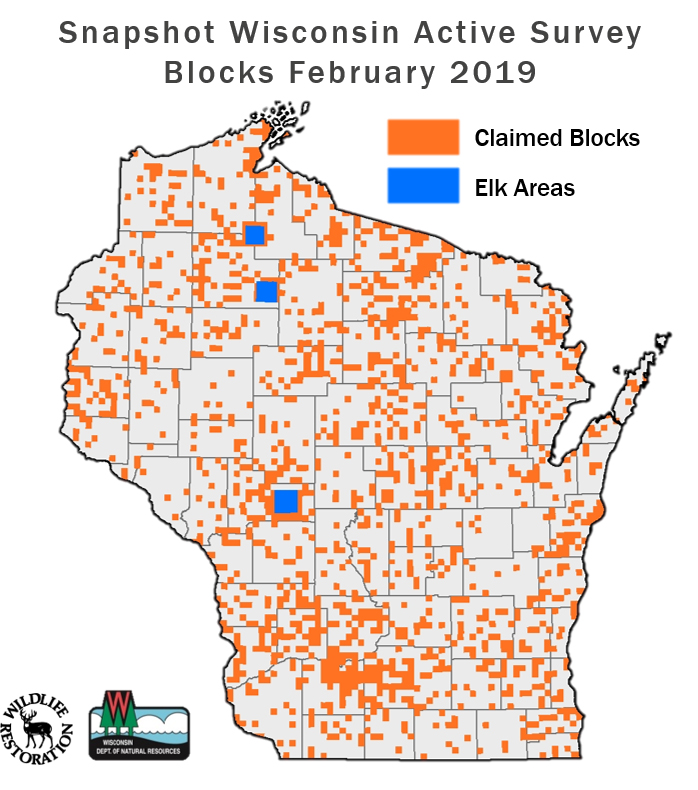

In the meantime, the DNR is focusing on expanding the trail camera network. After two years of pilot networks only in a handful of counties, Snapshot Wisconsin was expanded statewide in August 2018, Stenglein said. The near-term goal is to have a trail camera recording wildlife in 25 percent of the DNR’s 6,273 survey blocks around the state. Each survey block represents one-quarter of a township, or roughly 9 square miles. Eventually, Stenglein said, the hope is for full coverage statewide, or at least one camera in each survey block.

“Our goal is to have a trail camera in every single one of those survey blocks,” she said. “We’re just getting started though.”

Key facts

- Snapshot Wisconsin is unique among public trail camera efforts because it’s run by a government agency: the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

- One of the DNR’s goals with Snapshot Wisconsin is to increase the spatial and temporal resolution for all types of wildlife monitoring using one consistent method that is less time consuming and costly than other methods.

- Snapshot Wisconsin is intended to involve as many people as possible in the monitoring process, including volunteers to manage trail cameras and others who identify wildlife when the images are posted online. The crowdsourced identification process on Zooniverse requires roughly 15 different volunteers to agree on the identity of a species before it is confirmed as identified and enters the DNR’s database.

- The photos Snapshot trail cameras take are encrypted. Volunteers responsible for maintaining the cameras upload the images, which are stored on an SD card, to a special program that decrypts the photos and uses artificial intelligence to remove any photos that might include a human. The photos are then sent back to the volunteer who uploaded them, who double checks that none contain humans and upload them to Zooniverse.

- The trail cameras shoot three photos every time they are triggered. This series of three shots in a row helps with the classification of animals, especially those that move quickly across the field of view.

- Snapshot Wisconsin maintains a blog to share updates about the program, as well as some of the more dramatic wildlife photos the trail camera network captures. It also recruits new volunteers who want to maintain a trail camera.

Key quotes

- On Snapshot Wisconsin’s ability to expand the DNR’s wildlife monitoring statewide: “[Snapshot Wisconsin is] for the full extent of Wisconsin, whereas a lot of the methods we use, especially for furbearers and bobcats and things, are in the northern third of the state only, and so we don’t have a lot of information in the southern two-thirds of the state.”

- On the program’s global reach: “These photos that are collected by volunteers go then to this crowdsourcing site where thousands of people from all across the world help us determine what’s in them.”

- On the camera network’s extraordinary potential for monitoring wildlife: “[Trail cameras] take pictures all throughout the day. So, if we had a bunch of citizen scientists standing in the woods to help us monitor our wildlife the same sort of way, we’d only get the information during daytime at best, and these cameras give us the information from nighttime as well.”

- On how Snapshot is helping monitor the state’s growing elk herds: “[W]e have an extra effort [in Jackson County, where there is a reintroduced elk herd] where the cameras are put more densely together and volunteers helping us to monitor those cameras. And, similarly, this is the existing elk herd up in Clam Lake at the junction of Sawyer, Bayfield and Ashland Counties, and also for monitoring the elk herd where the cameras are spaced a little bit more closely together.”

- On the ability of Snapshot Wisconsin to create personal connections between humans and wildlife: “This project is actually all about individuals. It’s all about photos of individual animals. And that’s really kind of been taught to me by the volunteers in our project talking about what they’re seeing on their trail cameras. And, actually, an artist named Valerie, who takes the trail camera photos from her camera in the driftless area as inspiration for her art. She sees the individuals in these photos, and that’s really the focus. And I really like this about this project. Even though it’s not something we set out for as a goal, I think the individual component is what keeps people really attracted to it.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us