Return of Vilas County land by Catholic nuns to Lac du Flambeau breaks new ground

A land transfer to the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians by the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration is believed to be the first land-back effort by nuns in an attempt at reconciliation, with church entities still owning potentially more than 10,000 acres of lands once owned by tribes.

ICT News

January 7, 2026 • Northern Region

John Johnson, right, chairman of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, signs the paperwork confirming the transfer of the Marywood Franciscan Spirituality Center back to the tribe on Oct. 31, 2025, in Arbor Vitae. Looking on are Larry Turner, of the Lac du Flambeau Business Committee. and Sister Sue Ernster of the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

The ceremony was modest, with a handful of tribal leaders and a few citizens looking on as Catholic nuns signed over about two acres of land to the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, land that originally belonged to the tribe.

The historic transfer of the Marywood Franciscan Spirituality Center along Trout Lake in Arbor Vitae in northern Wisconsin was heralded by the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration as an important gesture of reconciliation for generations of Catholic participation in colonial land and resource grabs from Native peoples.

Believed to be the first of its kind by an order of Catholic nuns, the land transfer – in exchange for the land’s original purchase price of $30,000 – was considered a mighty win-win for both the tribe and the nuns.

“It was painful to address our complicity but we knew it had to be done,” Sister Eileen McKenzie, former president of the order, said in a statement. “We wanted to leave a legacy of healing.”

Sister Sue Ernster, the current president, said the nuns hope the land return can be a model for future Catholic efforts.

There’s no shortage of opportunities.

For the Catholic Church, widely considered to be among the largest non-governmental landowners in the world at about 177 million acres, there are conceivably many potential parcels that could be returned to make amends for its history of profiting from and participating in colonialist land grabs.

Although the exact amount is unknown, the church received thousands of acres of Native lands free of charge from the federal government during the so-called allotment era, from 1887 to 1934 and beyond.

Catholic leadership in the U.S., including the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions and the U.S. Council of Bishops, declined to comment on the amount of Indigenous lands it still owns today.

But an investigation by ICT found documents at Marquette University in Milwaukee indicating that church entities may still own more than 10,000 acres of land once owned by tribes. Additionally, ICT found that the church siphoned away millions of dollars in Indian trust and treaty funds to operate the notorious boarding schools.

Native activists note that the vast swaths of Indian lands contributed to the church’s historic ability to amass generational wealth and political influence in the United States.

They say it’s time to give it back.

“Before applauding the order too quickly, we need to take a moment to understand that their land return is a mere two acres out of 10,000 or more acres that the Catholic Church still owns,” said Ben Barnes, chief of the Shawnee Tribe and board chair of the Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

The nuns say they sold land they say no longer needed to the tribe at a fraction of its market value. They describe the sale as “an act of restoration and accountability and repair for colonization and Indian boarding schools.”

Seeking answers

The land returned by the nuns to the Lac du Flambeau tribe was not allotted to the order. That land was surrendered by the tribe via 19th century treaties before ending up in the hands of non-Natives and later purchased by the nuns in 1966.

From 1883 to 1969, the nuns operated St. Mary’s Indian Boarding School on the Bad River Ojibwe reservation. Some children from Flambeau attended, but the student population at St. Mary’s was overwhelmingly from the Bad River reservation.

In a statement released by the tribe, Chairman John Johnson said, “This return represents more than the restoration of land — it is the restoration of balance, dignity and our sacred connection to the places our ancestors once walked.”

According to the Franciscan Sisters and Land Justice Futures, a nonprofit organization that assists religious groups returning land for racial and ecological healing, the two-acre return by the nuns to the tribe is a first for a Catholic institution to do so in the name of reparations for colonialism and boarding schools. It is the first land return among clients of Land Justice Futures, which began working with the Franciscan Sisters three years ago on a way to reckon with the order’s boarding school history.

In past interviews with ICT, Kathleen Holscher, chair of Roman Catholic studies at the University of New Mexico, said that boarding schools played a number of important roles for the Catholic Church. Mission work with Native Americans elevated the church in the eyes of the general public, for example, as Catholic missions came to be seen as integral to the American project of “civilizing” the American wilderness.

Although the church issued apologies for its role in operating boarding and residential schools in Canada in 2022 and the U.S. in 2024, many Native leaders complained about the failures of the church to include mention of specific impacts of its policies, such as physical and sexual abuse or the number of children who perished at the schools.

Nick Tilsen, chief executive of NDN Collective, expressed disappointment that the 2024 U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishop’s apology included assertions of positive effects of the schools.

“If you’re going to give an apology, just apologize,” Tilsen told The New York Times. “How many times have people taught their children: ‘Don’t say sorry and then say, but…'”

Indeed, the Franciscan Sisters’ land return was not a gift, though leaders of the order described the payment of $30,000 by the tribe as a “nominal fee.”

The fee, however, is nearly double the annual average income of about $17,000 on the Lac du Flambeau reservation, where 20 percent of the population lives at or below the federal poverty line, according to the federal Administration for Children and Families.

A sign greets visitors to the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians reservation in northern Wisconsin. (Credit: Mary Annette Pember / ICT)

Jane Comeau, a lay employee who works with the order’s media team, told ICT in a joint telephone interview with Ernster in November that the price represents about 1 percent of the land’s current worth, which is estimated at about $2.5 million, and that it is the same price the nuns paid for the property more than 60 years ago.

Representatives of Land Justice Futures had previously told ICT that whenever possible, they recommend returning such land as a gift. ICT questioned the sisters about why the order required the tribe to pay a fee for land that was being returned as an act of healing and accountability.

“That’s a very good question,” Comeau responded. The call then went silent for nearly 60 seconds before Comeau responded further.

“I have the sense that no matter how I answer, it’s not going to be enough for you,” Comeau said at last.

The nuns did not explain their decision further except to say that the deal is what the organization agreed upon.

‘Civilizing the pagan Ojibwe’

There doesn’t appear to be any legal reason preventing the order from simply gifting the land to the tribe, according to attorneys contacted by ICT. The attorneys represent other tribes in the Great Lakes area and asked not to be identified by name over concerns of creating liability for their clients.

Former nun Carie Novitzke, who left the Fransciscan Sisters to pursue a doctorate in the mental health field, said the order may have been concerned that an outright gift could be construed as a tacit admission of past acts of child abuse at St. Mary’s exposing the order to legal and financial liability.

During an interview with ICT news partner PBS Wisconsin, Ernster insisted that the nuns did not abuse the students at St. Mary’s and ran the school according to assimilationist rules set by the federal government, keeping children safe in the process.

Interviews with scores of former students at St. Mary’s as well as the order’s own history, however, tell a different story. Survivors describe brutal punishment including withholding of food as well as beatings they endured or witnessed of other children by the nuns.

Jan Conners of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa described her days at the school in the 1950s when she attended day school at St. Mary’s. “The worst beatings occurred behind closed doors and involved the children who boarded at the school,” she told ICT.

Impoverished children who were forced to board at the school were often called convent girls or boys.

Conners recalled being told a story of a nun who lost her temper. “The nuns wore these wide leather belts with big black buckles,” she recounted. “That nun completely lost her temper, took off her belt and beat one of the convent boys until he bled.”

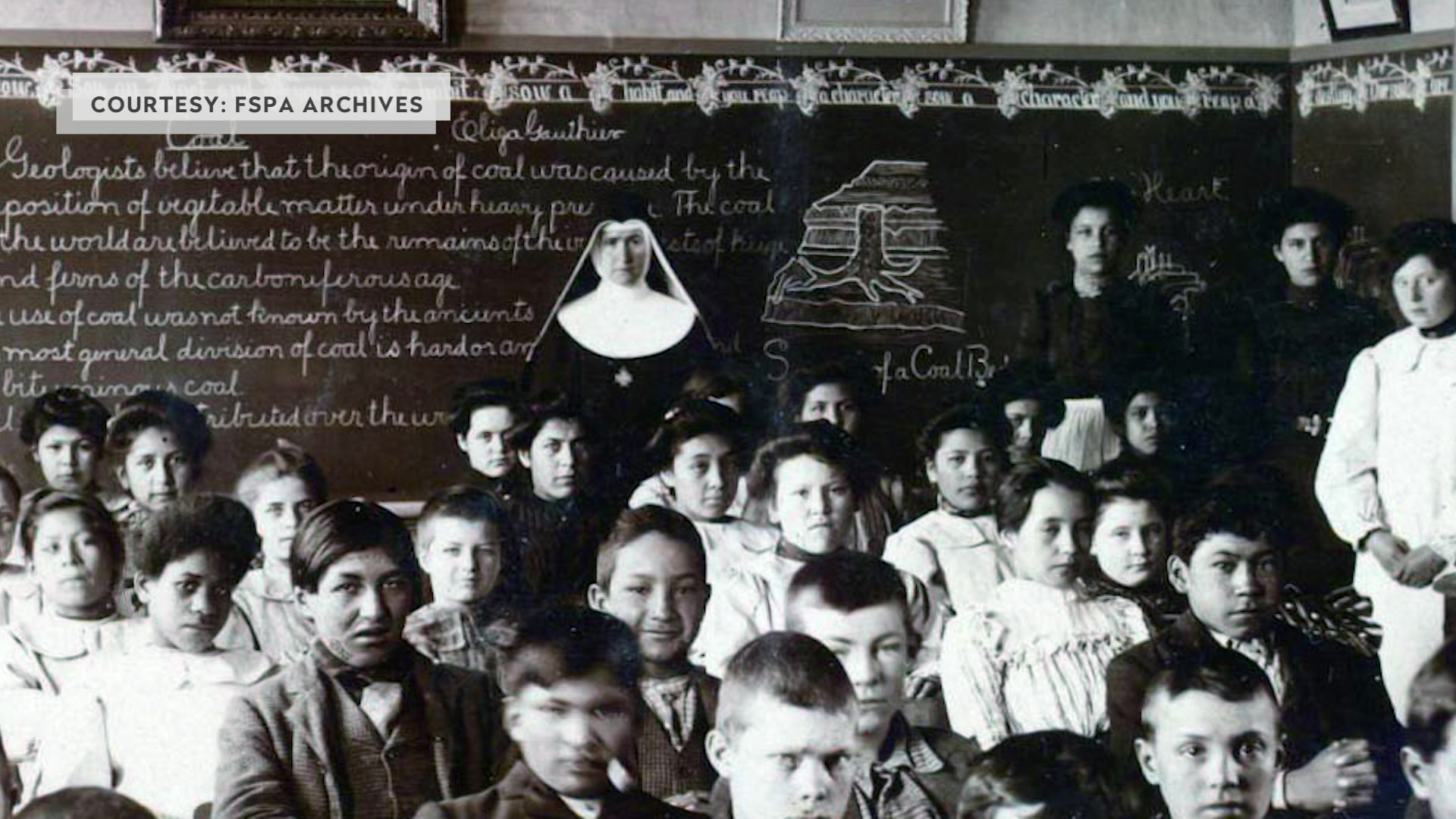

An archival photo from the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration depicts nuns teaching students at the St. Mary’s Indian boarding school on the Bad River Ojibwe reservation in northern Wisconsin. (Credit: Courtesy of Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration)

According to the order’s own history, documented in “A Chapter of Franciscan History: The sisters of the third order of Saint Francis of Perpetual Adoration,” published in 1950, the nuns arrived in Bad River in 1883 with a mission focused on “civilizing the pagan Ojibwe through conversion and education.”

Later, they successfully secured financial support from the federal government for the work. It was Christian missionaries who first launched the notion of dealing with the country’s so-called “Indian problem” – removing Native people as a barrier for White settlers – through forced conversion and education. The federal government later embraced and supported their efforts, making it a part of federal Indian policy.

Land Back movement

As Catholic and other Christian organizations dive into the growing Land Back movement, a social justice movement designed to restore lands taken from tribes by the federal government and others, they will likely find themselves to be far bigger players than they had imagined.

During the late 19th and into the mid 20th century, the federal government gave thousands of acres of allotted Indian lands free of charge to Christian missionaries, especially the Catholic Church, as a means to further the assimilationist agendas of church and government.

The Dawes Act, or Allotment Act, focused on breaking up reservation and tribal lands by granting allotments to individual Indians and encouraging them to take up farming. Much of these allotted lands were later taken from Native peoples in various schemes, some outright illegal. Churches received full allotments of 60 to 140 acres, the same as the heads of Native families.

Although Congress stipulated that once the allotted lands ceased to be used for church or school purposes, the land was to be returned to the government, the rule was seldom enforced.

And even after the Dawes Act was rescinded by passage of the Howard Wheeler Act or Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, there are several examples in the Congressional record of special presidential proclamations awarding tracts of Indian lands free of charge to Christian missionaries for churches and schools.

The practice appears to have gone on into the mid-20th century. These gifts were often done as “fee simple,” meaning the church owned the lands outright. It’s unknown how much of this land is currently owned by Catholic organizations.

Initially, the federal government gave the lands to the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, an administrative and lobbying entity based in Washington, D.C. that oversaw federal funding channeled to Indian boarding schools.

The archives for the bureau were transferred in the 1970s to Marquette University, where ICT found a document describing Native lands, approximately 10,000 acres, held by the bureau that were later distributed to more than 130 Catholic organizations throughout the country.

Next steps

The return of lands – for a nominal fee or as outright gifts – are part of a growing effort nationwide to seek redress for the government’s brutal assimilationist policies and actions.

Johnson, the Lac du Flambeau tribal chairman, did not respond to requests for comment from ICT. In an interview with the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, however, Johnson said he is leading an effort to hold the Catholic Church responsible for its role in operating Indian boarding schools.

Johnson said the Lac du Flambeau tribe is working with several other tribes to create a formal resolution demanding accountability and payment to tribal members to help in reclamation of culture taken away.

In May 2025, the Wichita and Affiliated Tribes and the Washoe Tribe of Nevada and California filed a class-action lawsuit against the federal government seeking a full accounting of monies spent running Indian boarding schools.

And efforts continue in Congress to create a national commission to investigate Indian boarding schools. Legislation known as the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act was reintroduced in Congress in 2025 but at year’s end had not yet been passed in the U.S. House, despite deletion of a provision that would have given the commission power to subpoena churches for records.

Deb Parker, executive director of the Coalition and citizen of the Tulalip tribes, has described the subpoena power as “absolutely necessary,” but earlier versions of the bill that included subpoena power failed to earn support from Republicans.

Indeed, boarding school survivors, their descendants and supporters insist that while apologies and pursuing healing are important, they must be preceded by truth and accountability.

Denise Lajimodiere, a longtime boarding school historian and author of a collection of histories of boarding school survivors, “Stringing Rosaries,” said in an earlier interview with ICT, “Healing can’t begin without accountability, which requires releasing school records and acknowledging the cultural genocide that took place.”

Lajimodiere is a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa.

The Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration signed over land that was the location of the Marywood Franciscan Spirituality Center in Arbor Vitae to the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

The transfer of land to the Lac du Flambeau tribe is another step in the process. Though chairman Johnson eventually praised the return of the Marywood land, his initial response to hearing that the nuns wanted the tribe to pay $30,000 for the land was to make a counter offer of $1.

“I wasn’t trying to be sarcastic,” Johnson said in an interview with PBS Wisconsin. “It was our land to begin with.”

After learning that the land is currently appraised at over $2.5 million, Johnson agreed with the tribe’s business council that the price, $30,000, was a good deal for the tribe.

Larry Turner, of the Lac Du Flambeau Business Development Corporation, said the tribe is not expecting to make a profit from the land transfer and will use the property for professional housing.

“We have such a huge shortage of professionals in the tribe, including traveling nurses, doctors for the clinic, management for the Business Development Corp, and there’s no rentals up here,” Turner said.

Johnson said he also wants to use the reclaimed land to sustain their Ojibwe culture for future generations.

But does giving land back to Native Americans reconcile the past?

“It’s a step,” Ernster said. “It does not fully reconcile. There’s nothing I believe that can fully reconcile for the trauma that has been inflicted over these years.”

In his interview with ICT, Barnes added, “I would call upon the Order as well as the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops to push for passage of the Truth and Reconciliation Indian boarding school bill currently before Congress.”

Erica Ayisi contributed to this report as part of a partnership between ICT and PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us