Latino Immigrant Workers At Midwestern Asian Restaurants Find Themselves Isolated, Underpaid

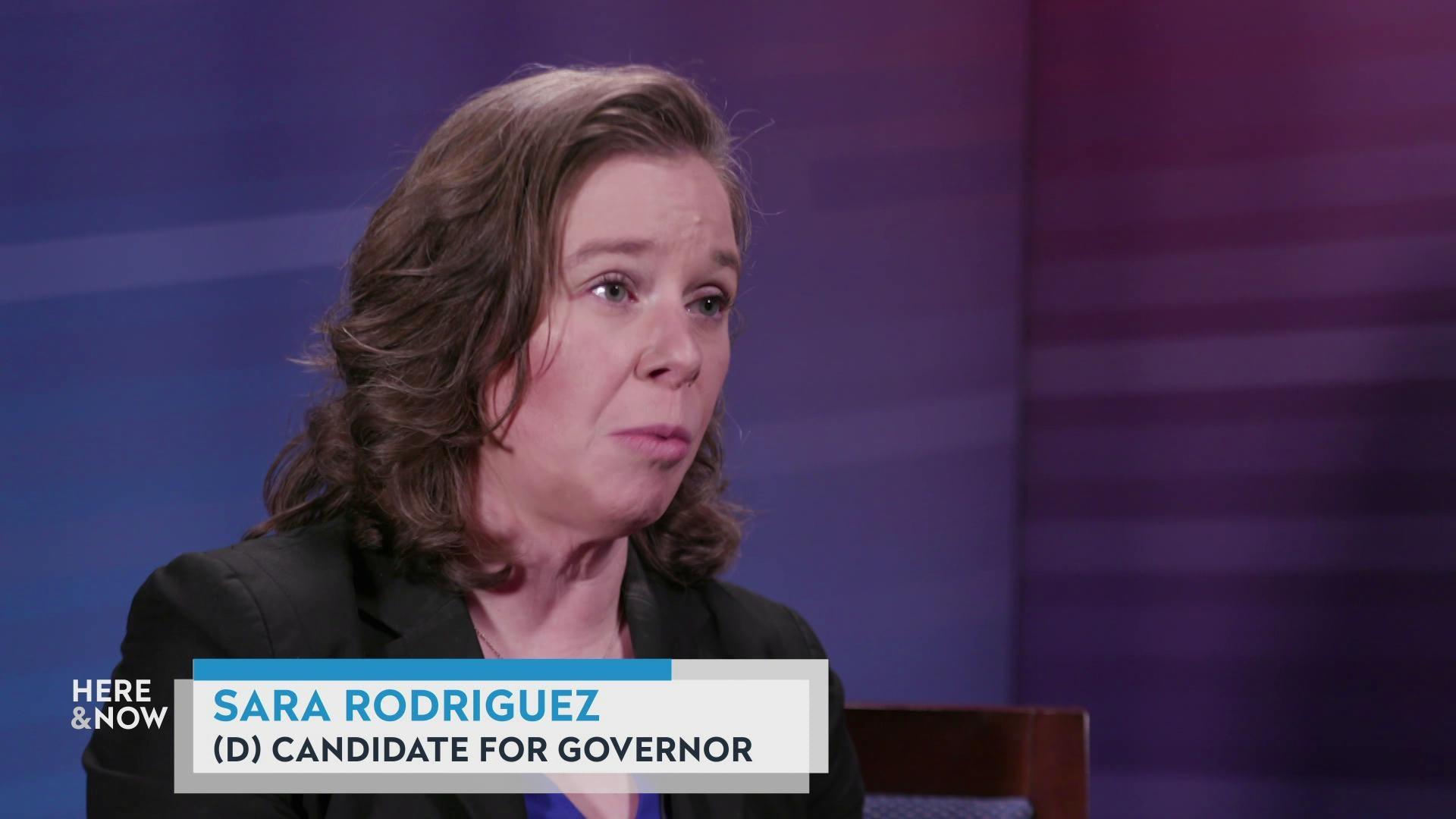

In 2015, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan sued three employment agencies in Chicago's Chinatown, and two Illinois restaurants that had used their services, for allegedly exploiting Latino immigrant workers in several states, including Wisconsin.

October 8, 2018

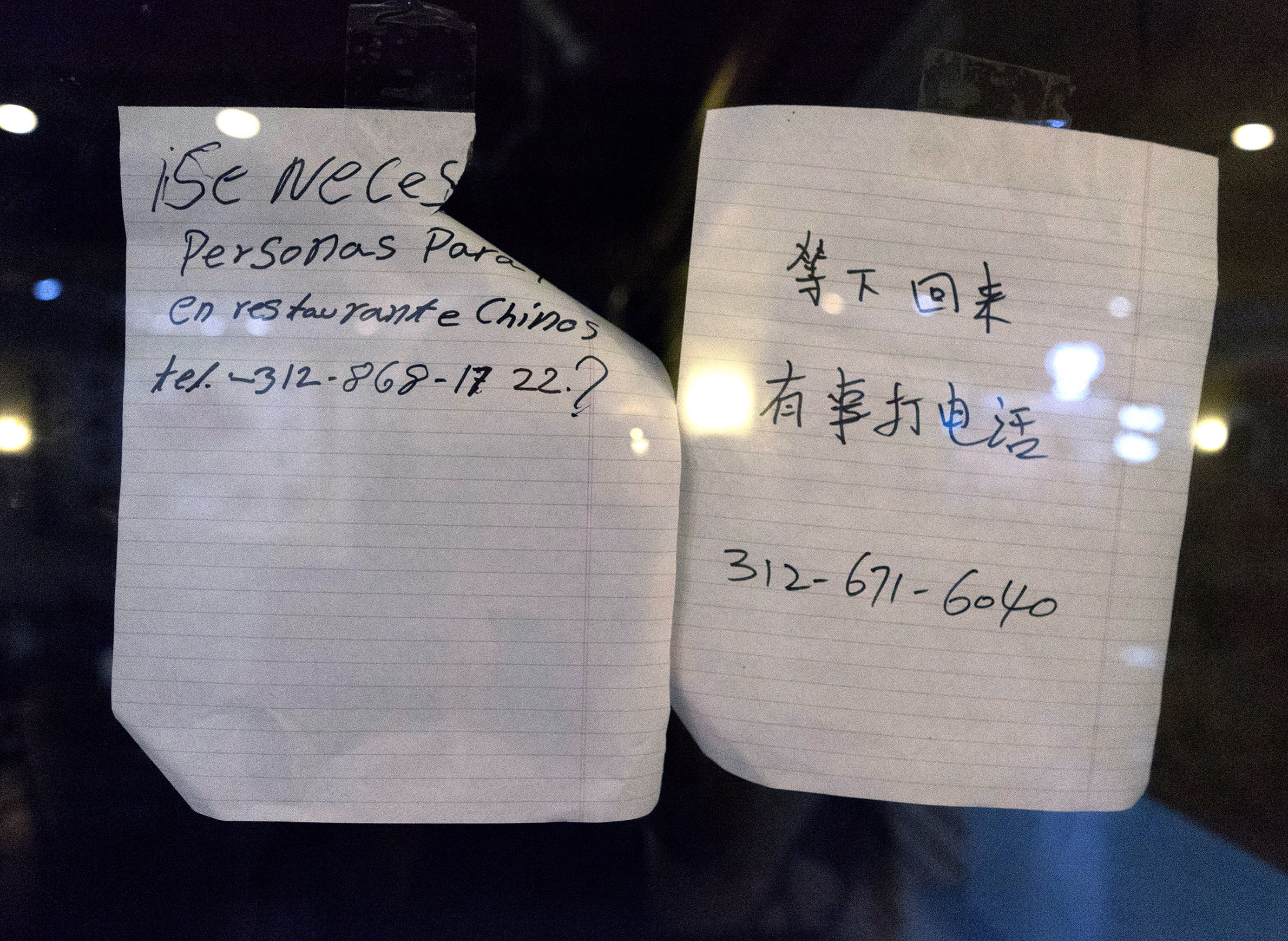

Latino employee at Chinese restaurant in Waukegan, Illinois

On a cool Monday evening in August, a few minutes after the 10 p.m. closing of Ping Tom Memorial Park in Chicago’s Chinatown, a group of men is settling in for the night. Some are from Guatemala, others are Mexican, and one is a U.S. citizen. Most of them are young. They crack jokes, drink beer and relax — some sprawled on bare mattresses, others lounging on dilapidated furniture amid an assortment of shopping carts.

Bright lights from the nearby baseball field flood a corner of the dimly lit camp, revealing discarded bottles and cardboard. The Chicago River is a few yards away, and downtown skyscrapers glitter in the distance.

Hidden by trees, behind railroad tracks, and next to a wall of concrete, the men live “debajo del puente” or “under the bridge.” Drivers and pedestrians on the busy 18th Street above are likely unaware of the men who live and sleep below them, or that many of them are the same people who chop vegetables, clean floors and refill buffets at Asian restaurants across the Midwest

Jose Luis Ruiz, a 39-year-old from Michoacan, Mexico, is lying on the mattress where he will spend the night, playing on his phone. He found his first job because of a newspaper ad looking for dishwashers. It included a place to live.

He said he works at Chinese restaurants all over the Midwest, putting in 12- or 13-hour days, making $2,000 a month. Each time he gets a job, he pays an employment agency a fee. Ruiz, and another man who asked not to be named, said they were paid less than minimum wage and no overtime while working at a Chinese restaurant near the Wisconsin-Illinois border.

The second man, who continues to work there, said during an interview in late September that he is paid in cash, leaving no record of his wages or hours worked. He said the managers are nice and provide a decent place to live, but the pay is too low.

As he took a break from mopping the floor of the Waukegan, Illinois, restaurant, the man said there are not many options for undocumented immigrants. “What can we do?” he asked in Spanish. Efforts to reach the owner to ask about the workers’ pay were unsuccessful.

As for Ruiz, he planned to get up early the day after the interview to take the Amtrak to Detroit to work at a buffet.

“This work has not gone well for me,” Ruiz said in Spanish. “We work, but sometimes they treat us bad. They kick us out of the jobs, but we don’t have other options.”

Illinois attorney general alleges exploitation

In 2015, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan sued three employment agencies in Chicago’s Chinatown, and two Illinois restaurants that had used their services, for allegedly exploiting Latino immigrant workers in several states, including Wisconsin. Many of the workers, the agencies acknowledge in court records, are undocumented.

Despite an abundance of local labor in their locales, the restaurants rely on the referral services of the Chicago-based agencies because they provide “‘Mexican’ workers that the restaurants can pay below minimum wage and discriminate against, seemingly without consequence,” according to one of the pleadings in the lawsuit.

The lawsuit filed in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Illinois said “employment agencies essentially acted as central supply houses for a buffet restaurant industry seeking to profit from illegal and exploitative wages and conditions of employment.” Over a period of five years, they “systematically selected and dispatched vulnerable Latino workers to abysmal working conditions in restaurants inside and outside Illinois,” the lawsuit said.

The lawsuit described workers’ “squalid” living conditions at accommodations provided by one of the two Illinois restaurants sued in the complaint.

“The employer Elk Grove Village Hibachi Buffet crowded as many as fifteen employees into a three-bedroom apartment with just one bathroom, and no furniture aside from soiled mattresses, which employees had resorted to finding themselves from a nearby garbage dumpster,” the complaint alleged.

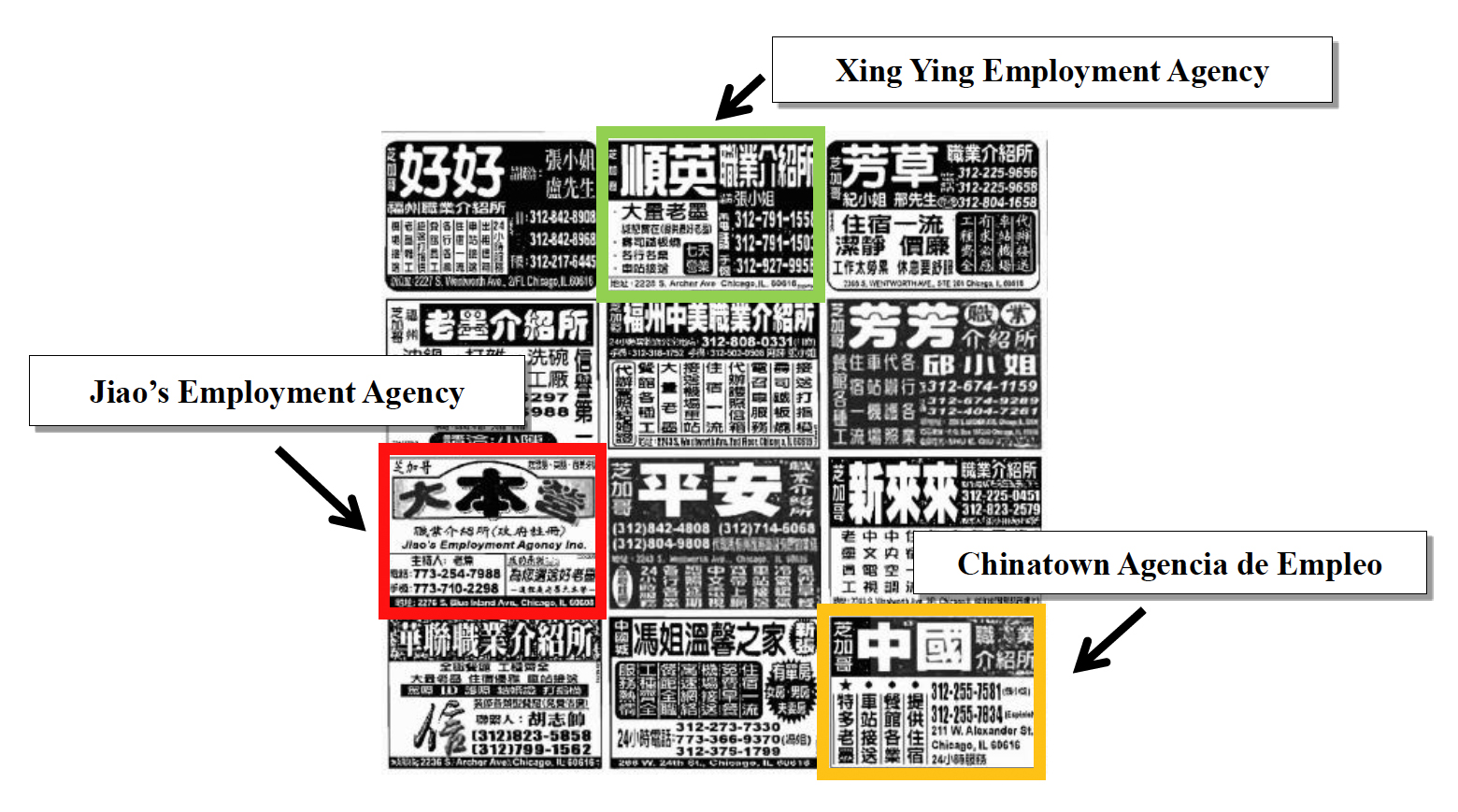

The lawsuit includes copies of checks showing that dozens of eateries in Illinois and around the Midwest, 11 of them in Wisconsin, employed workers from Xing Ying Employment Agency, Jiao’s Employment Agency and Chinatown Agencia de Empleo, all located within two miles of each other in Chinatown.

The lawsuit claims that the agencies and their restaurant clients “collectively set the wages for each Latino worker referred as low as $3.50 an hour, well below the $8.25 minimum wage in Illinois.” Wisconsin’s minimum wage for non-tipped employees is $7.25.

The owners of Xing Ying, Jiao’s and Chinatown Agencia denied the allegation in responses filed by their lawyers, arguing that wages were set at the request of the prospective worker and employer — not the agency.

Wen Bin Ren, a former head chef at one of the Illinois restaurant companies named in the suit, described to investigators how he hired workers from the employment agencies.

“The way the process worked is that I would call one of these agencies and tell them what Hibachi Grill was looking for in terms of an employee and how much Hibachi Grill would pay,” he said in a written statement included in the lawsuit. “My recollection is that China Employment Agency and Shun Ying [Xing Ying] could provide either Chinese or Mexican workers, depending upon what the restaurant was looking for.”

The employment agencies charge employers between $120 and $220 for each worker, who are then required to repay the fee through their paychecks, the complaint alleges.

Employees reported working 12 to 14 hours a day, six days a week, without meal breaks. Workers interviewed by Madigan’s office described high-pressure work environments, verbal abuse and threats of violence.

Wisconsin restaurants named

According to an exhibit attached to the lawsuit, the following Wisconsin restaurants paid the agencies for workers between 2010 and 2016: Asia Palace, Fuji Sushi and Steakhouse and Golden Dragon in Eau Claire; Meiji Restaurant in Waukesha; Lucky Panda Restaurant in Osceola; New King Wok in Janesville; Kiku Japanese Restaurant in Milwaukee (currently closed); Asian Kitchen and Jade Garden in Madison; China Buffet in Tomah; and New Hibachi Buffet in Stevens Point.

Paul Zhang, manager of China Buffet, said he had not hired workers from Xing Ying “since years ago” — the last check from his restaurant to the agency is dated August 2015. Zhang also said he stopped using Xing Ying to hire workers because every time he called the agency, it did not have enough people.

China Buffet no longer employs Spanish-speaking workers, Zhang said, and all current employees are Chinese. He said they are paid the state minimum wage and live in a house provided by the restaurant, where each has his or her own room.

A Fuji Sushi and Steakhouse employee said that restaurant changed ownership in 2017 and would not elaborate on the restaurant’s current hiring practices. Employees from Golden Dragon and New Hibachi Buffet (now called Asian Buffet) also said their restaurants changed ownership recently, and could not comment on the payments to the employment agencies.

A person who identified himself as the manager of Jade Garden said the restaurant had not used any employment agency for a “long time” because it had not hired any new employees recently then quickly hung up. The other restaurants did not respond to requests for comment.

Meiji, a Chinese and Japanese restaurant, has also been investigated by the U.S. Department of Labor for violations of the Fair Labor Standards Act from 2014 to 2016. A case narrative obtained by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism through the federal Freedom of Information Act found the restaurant owner, Cai Long Huang, failed to keep records of the kitchen staff’s working hours. So when one worker (through a translator) told investigators he worked 60 hours a week, there was no evidence to show them.

According to the case narrative, Huang stated that none of his employees work overtime and “he was candid that he did not know the laws.” He was charged with 20 Fair Labor Standards Act violations, including failure to pay minimum wage and overtime and other counts. Last year, he was ordered to pay a total of $7,180 in back wages to 17 employees.

A Meiji employee declined to provide the owner’s contact information, and the restaurant did not respond to calls and emails for comment.

Shuttled from job to job

Beto, a 27-year-old from Guadalajara, Mexico, told reporters from the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism and the Chicago Sun-Times that he encountered exploitative conditions while working in restaurants through employment agencies in Chicago, including Xing Ying. Beto asked that his last name not be used, out of fear of deportation and losing work with the restaurants. He declined to be photographed. Beto said he continues to work at restaurants but no longer gets work through the agencies.

In the basement of a mall in Chicago’s Chinatown, seated outside a pair of nondescript and sparsely furnished employment agency offices, Beto recounted in Spanish and English being shuttled among Asian restaurants throughout the Midwest. He usually worked 11 or 12 hours a day, often without breaks.

A referral slip he gave the Center from Xing Ying, dated late June 2018, shows that he was headed to a restaurant in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, to work for a $2,100 monthly salary. He was charged $100 for transportation, along with a $100 fee.

Referral slips from the other agencies included in the lawsuit show a monthly lump sum is promised to each worker per job. The sum is not adjusted based on the number of hours employees actually work, the lawsuit alleges, so the salaries “typically fall far short of the minimum wage required by law.”

As a waiter, Beto said, he was one of the better paid workers, earning between $6 and $7 an hour, but he was not allowed to keep tips. Because it was a higher-paying position, it cost him $200 each time he got a new job.

Beto said he started getting jobs through Chinatown employment agencies about two years ago. His first job was in Appleton, Wisconsin — one of many restaurants where he has worked.

“Sometimes you don’t know where you are. Sometimes they’ll tell you, ‘You’re going to Indianapolis,’ and when you are in Indianapolis, some people go for you and take you to another place, like little towns.”

He said the jobs can be fleeting. One time, an employer sent him back to the agency because she did not like his tattoos.

“If the guys [restaurant owners], don’t like you, they send you back, they don’t care if you don’t have any money. If you don’t do your job good or fast or something, you’ll go back,” Beto said.

Beto described living in the winter in cold apartments or a wet basement provided by his employers. He said work hours were long — “you spend a lot of hours in the restaurant, more than the house” — with sometimes just white rice to eat.

“Sometimes, the guys cooking for you don’t want to spend too much money on you,” he said.

Fired and evicted

Beto said if a worker spoke out, he could be threatened with calls to police and deportation. So he and other employees learned not to speak up.

During a recent visit by reporters to the Xing Ying agency for this story, Beto broke that rule.

Beto said he was fired after one of the owners discovered he had spoken with the reporters. His belongings were placed on a bench outside the locked front door of the agency. He said he was also evicted from another employment agency where he had planned to spend the night.

Beto said most of his co-workers were Mexican, and the rest were Chinese. The Mexicans, he said, are “more cheap.”

In March, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan won partial summary judgment against Xing Ying for placing discriminatory ads in the World Journal that offered to “provide the best Mexicans” who are “sincere” and “honest.” The Chinese-language newspaper’s Midwest edition is distributed in Illinois and other states including Wisconsin, and it also has an online edition.

A copy of the World Journal obtained in Wisconsin and translated by the Center in June 2018 still contained advertisements from various agencies, not including Xing Ying, offering restaurant jobs and benefits like shuttle services to bus stations. The ads did not mention Mexicans or Latinos.

Chilly reception at employment agency

Zhu Ying Zhang (known as “Cindy” to workers) and Jun Jin Cheung own and operate Xing Ying, which at the time of the lawsuit had a Chicago business license but was not a licensed employment agency by the state Department of Labor, according to court documents.

Zhang, who runs the day-to-day operations, said in Chinese that she had not taken out advertisements in the newspaper for years, but that she continued to send workers to restaurants “everywhere.”

During a recent visit, several mattresses were stacked against the wall in the second-floor apartment, and a row of rooms extended down a hallway on the right. About six workers were lounging around the mattresses, and several emerged from the rooms down the hallway. A camera was installed in the ceiling, directly above the exterior sleeping area. The kitchen was sparse, and also served as Zhang’s office.

When asked about the lawsuit, Zhang said she did not understand the question. She abruptly said she had other business to attend to and disappeared into one of the hallway bedrooms. Cheung, who is described in court documents as enforcing agency rules through threats and violence, did not speak but glared and smoked throughout a brief interview.

According to the lawsuit, Xing Ying charged up to 10 workers $10 a night each to stay at the employment agency, with many of them sleeping on the floor. Workers were told to “stay away from the windows,” according to the suit.

Back pay and a reprieve — for some

In a consent decree as part of the Illinois lawsuit, Hibachi Sushi Buffet in Cicero, Illinois, was ordered to pay a total of $96,000 in back wages to seven employees and penalties to the state. Hibachi Grill Buffet in Elk Grove Village was ordered to pay a total of $100,000 in back wages to four employees, plus penalties to the state.

Jiao’s Employment Agency also was ordered to pay the state $16,500, and Chinatown Agencia de Empleo went out of business. In August, the government reached a consent decree with Xing Ying, but the details have not been formalized, according to court records.

The Heartland Alliance, an anti-poverty nonprofit in Chicago, assisted three men who had worked in 2013 under the “same trafficking scheme” as the individuals in Madigan’s lawsuit, said Darci Flynn, associate director of the Heartland’s anti-trafficking team. Flynn said all were from Central or South America and worked together in the kitchen of a Chinese restaurant.

Flynn described it as a “a textbook labor trafficking case” and was frustrated that no criminal charges were filed.

“The only people who supported [the victims] were nonprofit social services and legal aid. The feds didn’t do anything about it. For those of us doing the case, we were talking about ‘This is labor trafficking. What are you going to do about it?'”

The men Flynn worked with are now living in their own apartments, taking English classes, and one even brought his wife to the United States, she said. All three received T visas awarded to trafficking victims who aid law enforcement in prosecuting trafficking cases.

Lisa Palumbo, supervising immigration attorney for the Chicago-based legal assistance group LAF, helped some of the workers in Madigan’s case. She said while those employees were allowed to stay in the country, many of the other workers were deported.

Beto said employees rarely get ahead working for the agencies because of the commissions and low pay.

“Almost nobody gains,” he said. “We don’t gain anything.”

‘They are all still there’

Chinatown employment agencies are adept at continuing operations, despite the scrutiny, said Jose Oliva, co-director of the Food Chain Workers Alliance, which works to improve wages and working conditions for employees who plant, harvest, process, pack, transport, prepare, serve and sell food.

“Even 10 years ago, when we started working on this, just in the six months during one of those cases, the agency disappeared and reappeared in another location,” said Oliva, who is based in Chicago. “There’s a pattern of taking advantage of the most vulnerable folks in society. [The agencies] are all still there, and they are all still in Chinatown.”

Carolyn Morales, an organizer at Arise Chicago Worker Center, which educates immigrant and U.S.-born workers on their rights and organizes them to improve workplace conditions, said “worker exploitation is rampant” because networks provide employees to restaurants across the Midwest and beyond. Workers have to pay recruiters’ fees, and they are housed by the employer.

“If you go to middle of nowhere in Illinois, there’s almost always a Chinese buffet,” Morales said. “It’s exploitative in all ends.”

The Tamer Center for Social Enterprise at Columbia University supported Belle Lin’s reporting through a fellowship at the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. Alexandra Arriaga is a digital content producer for the Chicago Sun-Times and a former intern for the Center, which collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us