Lake Trout Could Eat Their Way Back To Prominence In Great Lakes

Scientists may have settled a debate between anglers and fishery managers over the future of the lake trout in the Great Lakes.

February 11, 2018

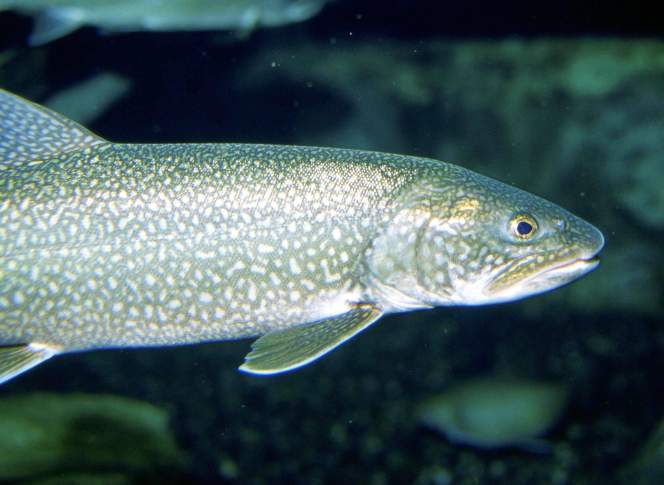

Lake trout underwater close-up

Scientists may have settled a debate between anglers and fishery managers over the future of the lake trout (Salvelinus namaycush) in the Great Lakes.

With salmon hauls on the decline in recent years as their favorite food dwindles, anglers are anxious to prioritize their protection even over recently resurgent native populations like lake trout.

Salmon reigned as the undisputed king of the Great Lakes fishing industry for decades after they were introduced in the 1950s to curb the invasive alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus). It was around that time that the highly lucrative lake trout fishery took a dive as populations crashed.

Alewife populations, the salmon’s key food source, have dwindled in recent years. Now anglers are afraid that the lake trout’s comeback could hasten the salmon’s disappearance and compete for the few alewife that are left, said Jory Jonas, a fisheries research biology specialist with the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

But that’s not necessarily true. Jonas is the co-author of a study published in January 2018 showing that lake trout eat whatever’s available, meaning they don’t always directly compete for food with species like the Chinook salmon(Onchorhynchus tshawytscha).

Both species mainly consumed alewife for years, Jonas said. That’s still true of most of the lake trout in Lake Michigan, where alewife populations are more stable. But though they’ve lost a main source of food, the lake trout’s flexible diet may make them beneficiaries after all.

“Nothing is ever truly good or bad,” she said. “It’s always a mix.”

Alewife consumption was probably harming lake trout eggs, said Austin Happel, who co-authored the diet study as a doctoral candidate at the University of Illinois. He’s now an instructor at Colorado State University.

Lake trout reproduction in the Great Lakes has been handcuffed for years due to chronically low levels of thiamine, a fat-binding agent key to a healthy egg membrane, according to the study.

Fish have to consume a healthy ratio of fat and thiamine to lay viable eggs – alewife are fatty and often low in thiamine, Happel said.

The goal for lake trout is self-sufficiency, he said. That’s not the reality these days. Lake trout have to be stocked for populations to survive.

The Great Lakes Fishery Commission seeks to protect native species like lake trout, said Marc Gaden, the commission’s communications director. But the agency is also pleased with each state’s efforts to save the salmon by growing the remaining alewife population.

“They have to take on this elephant in the room, which is that there’s not much food for the salmon to eat,” Gaden said.

Fishery managers face a balancing act. They need to support the alewife enough to meet the demand for salmon, while rooting against it – and in favor of other prey species – in the interests of the native lake trout.

The diets of lake trout differ drastically between lakes Michigan and Huron, and even between the east and west coasts of Lake Michigan. This kindles some hope for that balance managers need to protect both the salmon and lake trout, Jonas said.

The variation is consistent with availability – alewife in northern Lake Michigan still make up a large portion of lake trout diet, while the Lake Huron fish consume the more-abundant rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax). A booming population of round goby (Neogobius melanostomus), another invasive, is now an important food source for lake trout in western Lake Michigan.

But Happel said the alewife’s downturn won’t necessarily solve lake trout reproduction troubles. Thiamine deficiency has been found in other Great Lakes fish that don’t eat alewife – meaning the alewife might not be the crux of that problem.

“At some point we wanted to point fingers,” he said. “We wanted to find a culprit.”

Scientists have turned the log over only to find a larger problem – the entire food web in the Great Lakes is full of fat with not much thiamine to offset it, Happel said.

Alewife are a large part of the problem, but Jonas said prey like rainbow smelt are also low in thiamine to a lesser extent. The good news: round goby don’t share that problem. Researchers could start seeing higher natural reproduction among lake trout in goby-rich territory like Lake Michigan’s western shore.

Happel said the study is encouraging. If lake trout can diversify their diet – and with it, their vitamin intake – the odds look much better for reproduction.

Editor’s note: This article was originally published on Feb. 8, 2018 by Great Lakes Echo, which covers issues related to the environment of the Great Lakes watershed and is produced by the Knight Center for Environmental Journalism at Michigan State University.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us