How much new funding is available for Wisconsin's 2023 budget?

In attempts to justify their priorities, Gov. Tony Evers and Republican lawmakers are citing different numbers for what Wisconsin will have available to fund new programs over the 2023-25 budget cycle.

Associated Press

March 6, 2023

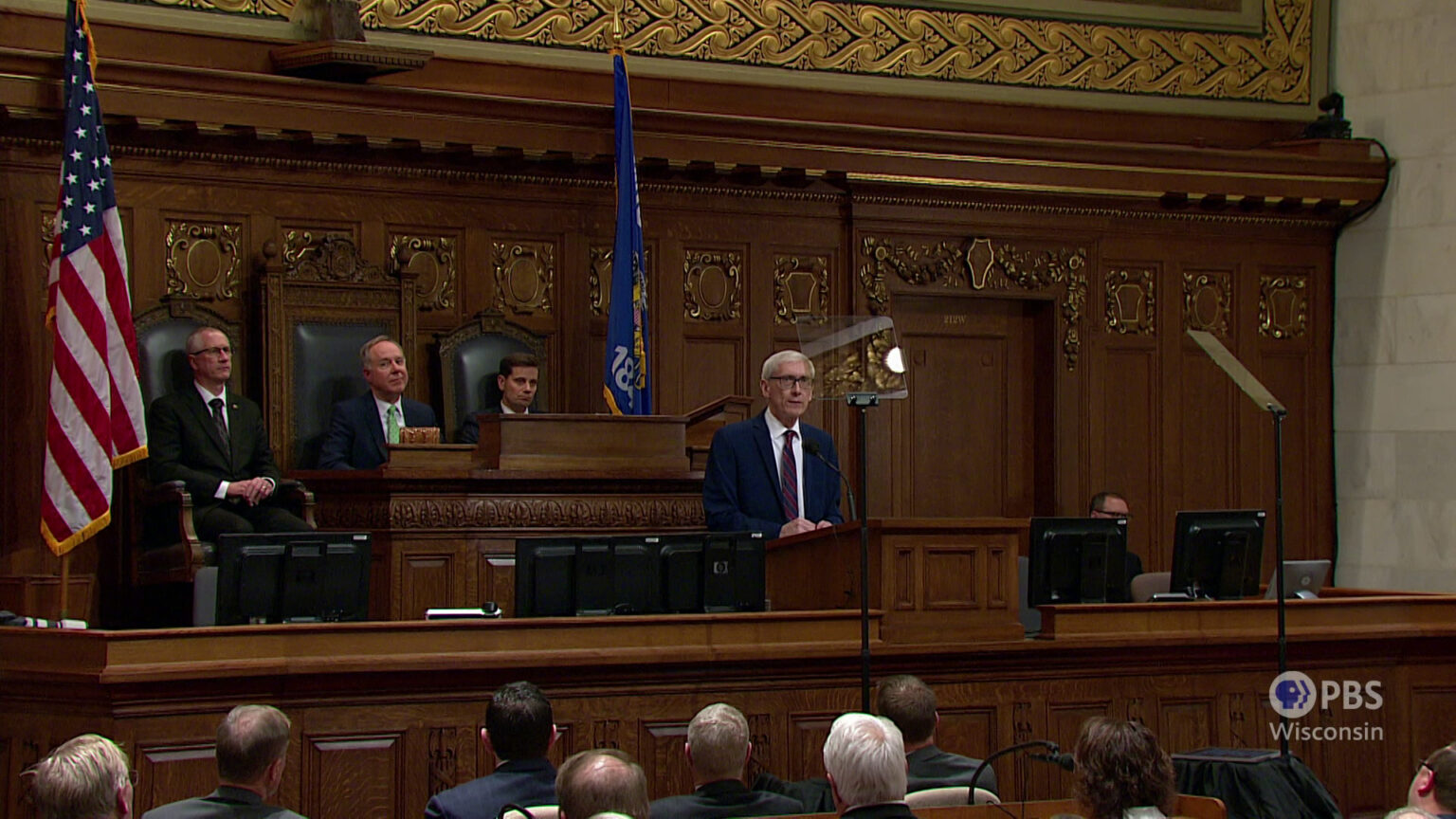

Wisconsin lawmakers listen to Gov. Tony Evers deliver his 2023-25 budget address on Feb. 15, 2023 in the Assembly chambers at the state Capitol in Madison. Republican lawmakers and Evers, a Democrat, disagree on how much extra money they have to work with in the 2023-25 state budget. In attempts to justify their budget priorities, Evers and Republicans are citing different numbers for what the state will have available to fund new programs. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

MADISON, Wis. (AP) — Republicans who control the Wisconsin Legislature and Democratic Gov. Tony Evers can’t seem to agree on how much extra money they have to work with in the state budget.

Attempting to justify their budget priorities, Evers, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos and the Republican co-chairs of the Legislature’s budget-writing committee cited three different amounts for what they expect to have at their discretion to fund new programs.

Here’s what current budget projections say about the money that’s available:

How much new money is up for grabs?

Wisconsin will start the two-year budget cycle with a record surplus projected at more than $7 billion, largely due to an influx of one-time federal pandemic relief funds.

State revenue, primarily from taxes, is expected to grow by $2.3 billion in 2024 and $3 billion in 2025, giving the state another $5.3 billion more than its base spending in 2023, according to the nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

What’s the difference between the surplus and tax revenue?

Increased tax revenue is ongoing. That’s money lawmakers can budget for new programs that will need funding year after year. The surplus comes mostly from one-time funding.

“You probably shouldn’t look to that for ongoing expenditures,” said Dave Loppnow, assistant director of the fiscal bureau. Evers and Republicans will likely try to direct the surplus funds to their priorities through one-time investments such as grant programs.

Evers laid out plans for several massive, one-time investments in his version of the budget, which includes $240 million to launch paid family and medical leave, billions in additional public school funding and $100 million to fight pollution from so-called forever chemicals known as PFAS.

How much money has already been earmarked?

The Legislature will work over the next four months to draft its version of the budget, which Evers can then reshape with partial vetoes. However, some of the increased revenue is effectively spoken for by the costs of continuing programs that were boosted by one-time federal funds, such as Medicaid and higher wages for correctional officers.

“Some of these things like funding Medicaid — the ongoing cost — you’ve pretty much got to do it,” said Jason Stein, research director at the nonpartisan Wisconsin Policy Forum. “You start to whittle away at your number.”

After accounting for continuing costs, the state will be left with about $2.4 billion from recurring revenue after the second year of spending, according to the fiscal bureau.

Are officials using ‘phony math’?

While downplaying the usefulness of surplus funds on March 1, Vos accused Evers of relying on “phony math” to construct his budget plan. A day earlier, Evers promised tax cuts for the middle class and additional funding for local governments.

“We do not have anywhere near the money that Gov. Evers spoke about yesterday,” Vos said.

But that could be true for both Republicans’ and Democrats’ plans, according to Stein. Republicans back a plan to enact a flat income tax rate, which would mostly benefit wealthy filers and could decrease tax revenue by almost $5 billion a year.

In the last fiscal year, Wisconsin collected about $9.2 billion in income taxes. Under the flat-tax plan by 2026, the state would collect roughly half as much, depending on inflation and other economic factors, according to the fiscal bureau.

“The very large increases in ongoing spending in the governor’s proposal and the very large ongoing tax cuts you would have to do if you were doing a flat tax, both of them would be difficult to sustain into the future,” Stein said.

Still, it’s unlikely either Evers or Republicans are relying on “phony math.”

“These things are an opening negotiating position for both sides,” Stein said.

Republicans showed signs of backing off on the push for a flat tax, when state Rep. Mark Born and state Sen. Howard Marklein, co-chairs of the Joint Finance Committee, said it was unlikely they would get all the way to a flat tax in the current budget.

Where are all the different numbers coming from?

Evers and Republicans have used different calculations to underscore aspects of the budget that fit their goals.

Evers, who wants to expand grant programs and dole out assistance to schools and the middle class, has highlighted the unprecedented one-time surplus as justification for increased spending.

Born and Marklein have focused on the annual increases in ongoing revenue — about $2.3 billion in 2024 and $3 billion in 2025. As co-chairs of the finance committee, they will oversee the allocation of that money to continuing program costs and new investments.

Vos, who has railed against Evers’ spending plan in favor of GOP-backed tax cuts and a balanced budget, based his statements on March 1 on the estimated $2.4 billion in ongoing revenue that will be left after two years of continued costs. He said that of the $1.2 billion available annually to spend on new investments, about 75% would be accounted for by continued costs of Medicaid and corrections wages. But according to the fiscal bureau, those amounts were already removed from the estimate it provided to Vos.

Vos’ spokesperson told The Associated Press on March 3 that Vos had mistakenly referenced the wrong numbers while speaking at a gathering of the Wisconsin Counties Association. It is unclear what other costs were accounted for in the estimate Vos cited. The fiscal bureau declined to provide the confidential memorandum it gave to Vos, and Vos’ office did not respond to requests for the information.

Harm Venhuizen is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us