Hayward Weighs The Risks And Costs Of The Next Deluge

The city of Hayward owes its existence to the waters and woods of northern Wisconsin, but the same geography that sparked and sustained the community's growth likewise heralds an emerging menace to its future.

By Will Cushman

August 23, 2019

Aerial photo of Hawyard with superimposed flood zones

The city of Hayward owes its existence to the waters and woods of northern Wisconsin, but the same geography that sparked and sustained the community’s growth likewise heralds an emerging menace to its future.

The seat of Sawyer County, Hayward is named for a 19th century lumberman, Anthony Judson Hayward, who based his company’s operations on a site along the Namekagon River in the midst of the region’s logging boom. Soon, a settlement of the same name sprang up around Hayward’s sawmill.

When loggers had cleared the region’s forests, Hayward embarked on a long transition toward a tourism economy based on outdoor sports. In the 21st century, Hayward hosts throngs of vacationers every year. In addition to angling on surrounding lakes, visitors come for the American Birkebeiner cross-country ski race and the Lumberjack World Championship, which both draw thousands of spectators and athletes each winter and summer.

The local landscape that is so appealing for outdoor recreation also sets the stage for an increasingly prominent threat: The flat, boggy land that settlers and subsequent generations built over makes Hayward vulnerable to flooding.

“Hayward is built on a swamp, a catacomb of underground rivers,” said Pat Sanchez, Sawyer County’s emergency management coordinator, in an Aug. 17, 2019 report on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now.

With a water table that is already relatively high and the prospect of more frequent and intense rainstorms in the future, much of the city sits in a zone primed for flash flooding. A huge storm in July 2016 affected a wide swath of northwestern Wisconsin, killing four people and causing tens of millions of dollars in damage to public infrastructure and private property, though the heaviest impacts were centered north of Sawyer County. Still, Hayward felt its effects, as it did with a more localized storm in September 2014.

“We have a lot of rivers, a lot of streams, a lot of lakes, and when we get [a] heavy downpour like we’ve had in the past years, there’s not anywhere for that water to go,” Sanchez said.

With the region experiencing more frequent and more intense rainstorms in recent years, and high costs associated with them, communities are attempting to better understand flood risks and how to protect against them.

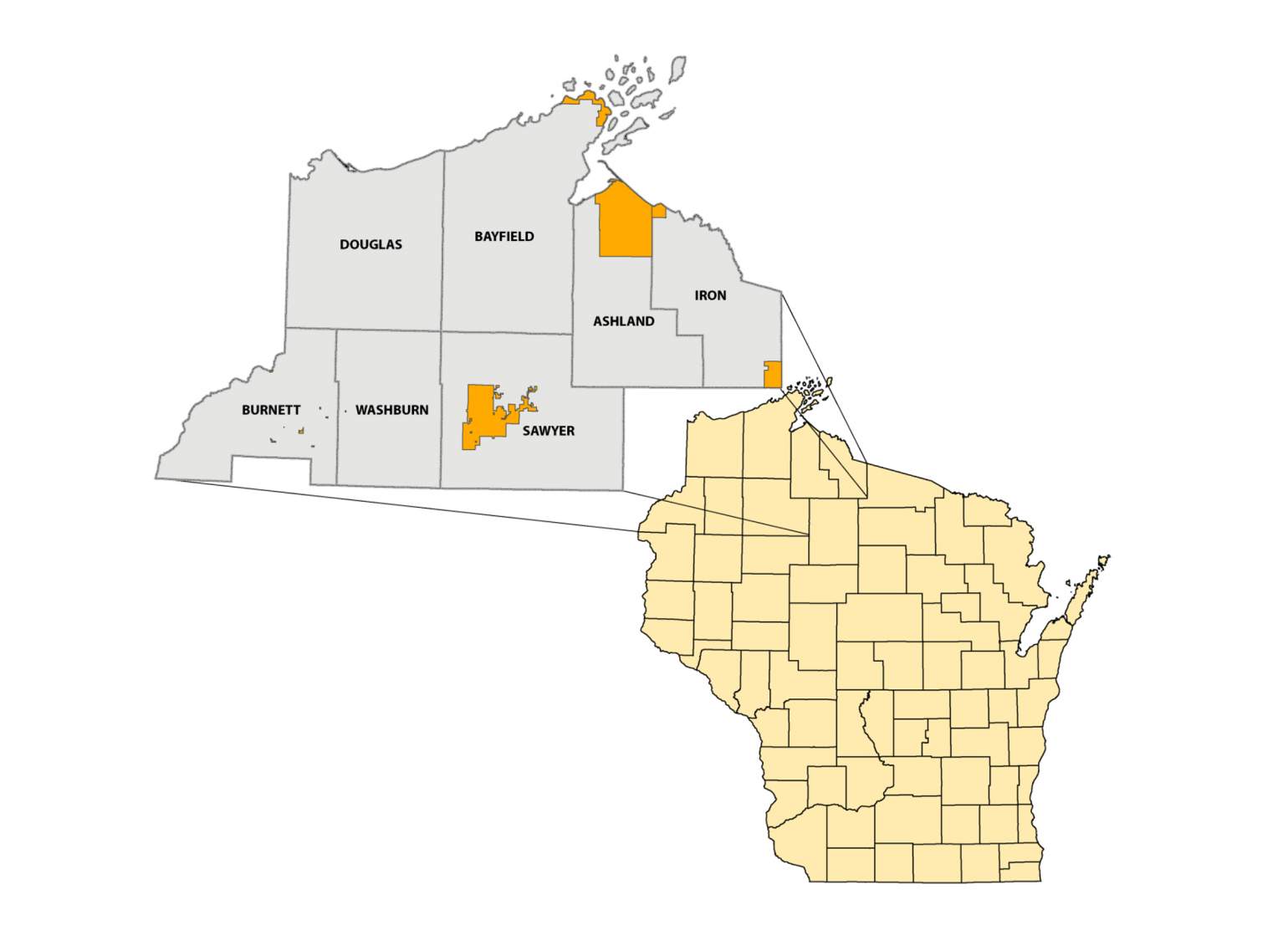

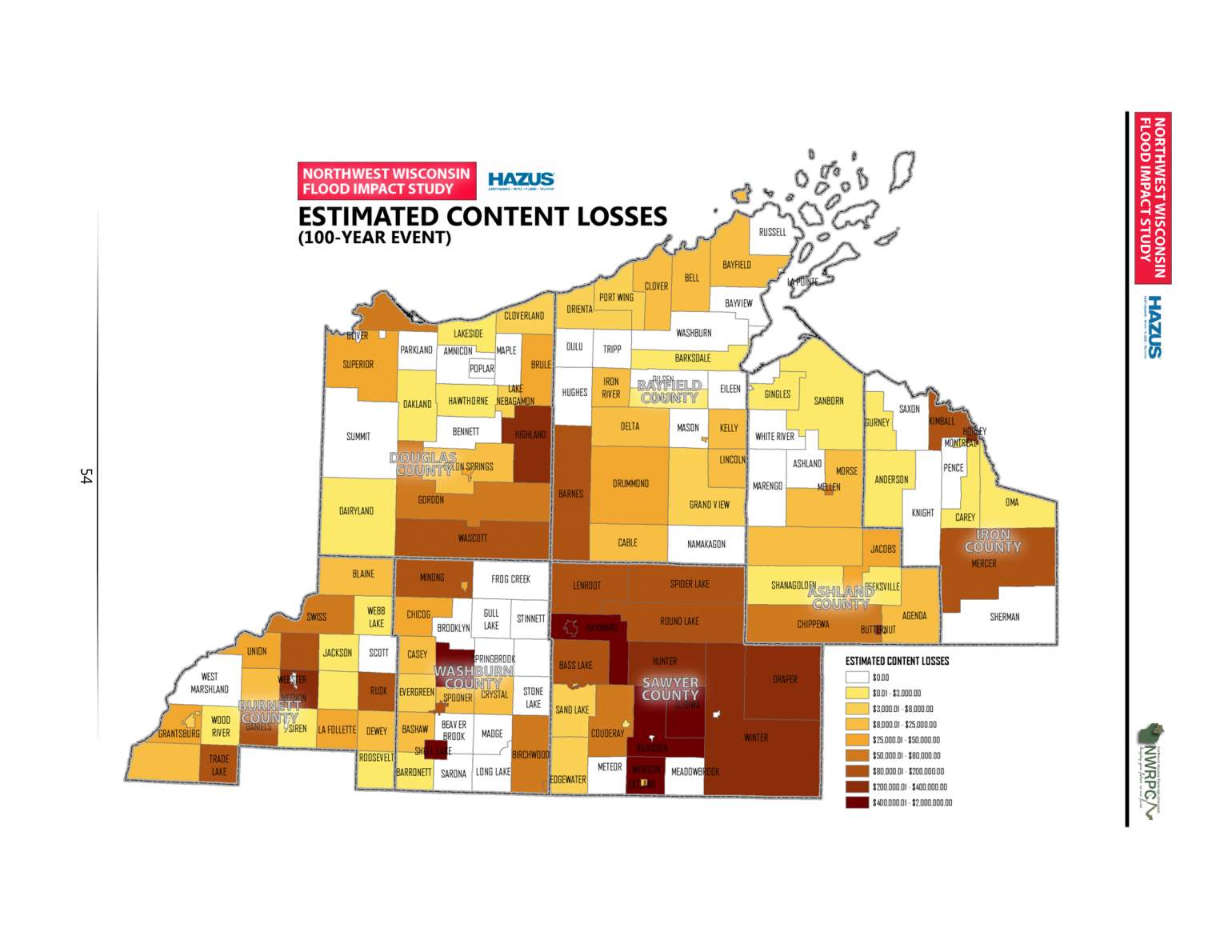

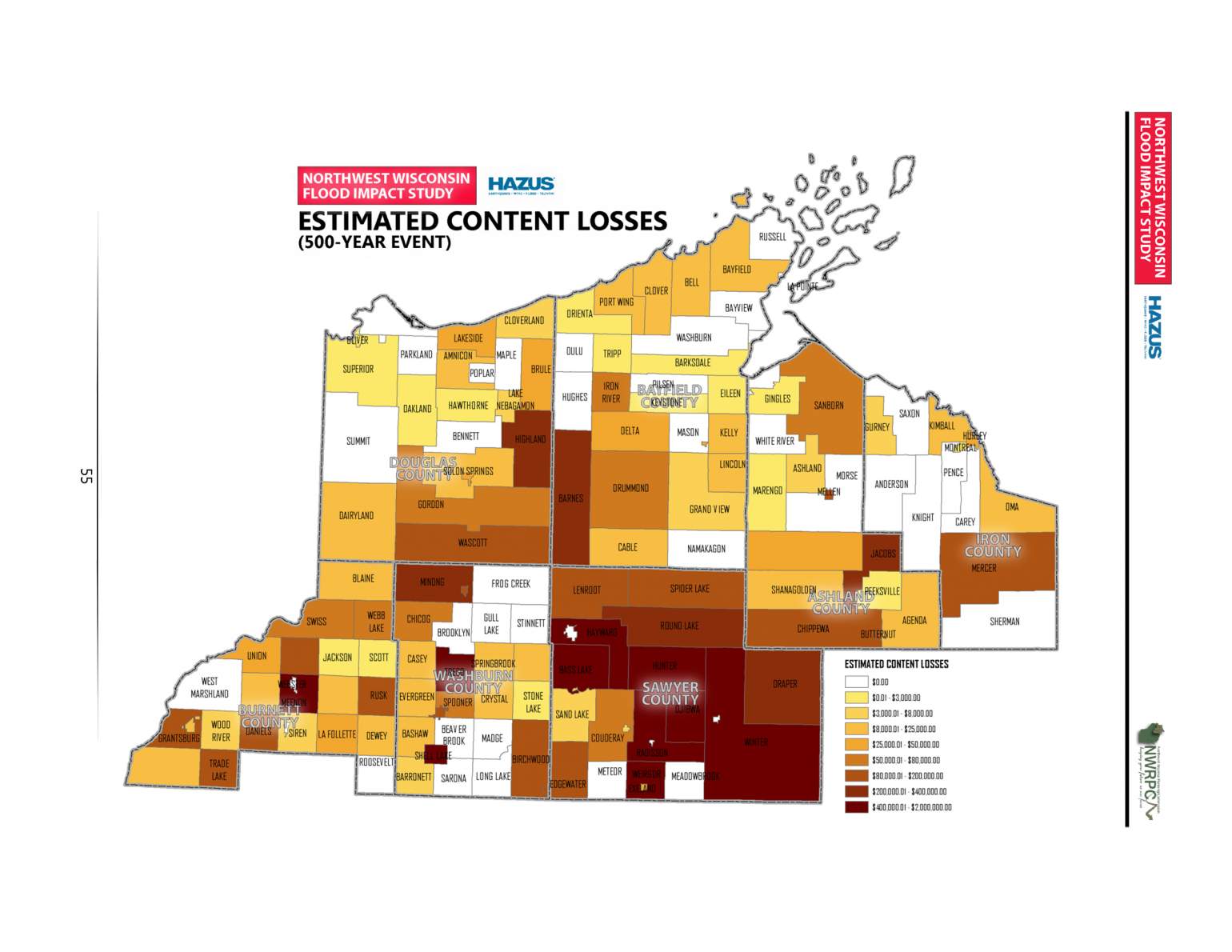

In fact, the risk of flooding extends well beyond Hayward and into surrounding communities. In 2018, the Northwest Regional Planning Commission, an intergovernmental organization of counties and tribal nations in northwestern Wisconsin, published a flood-risk study that highlighted Sawyer County’s relatively high vulnerability to flooding.

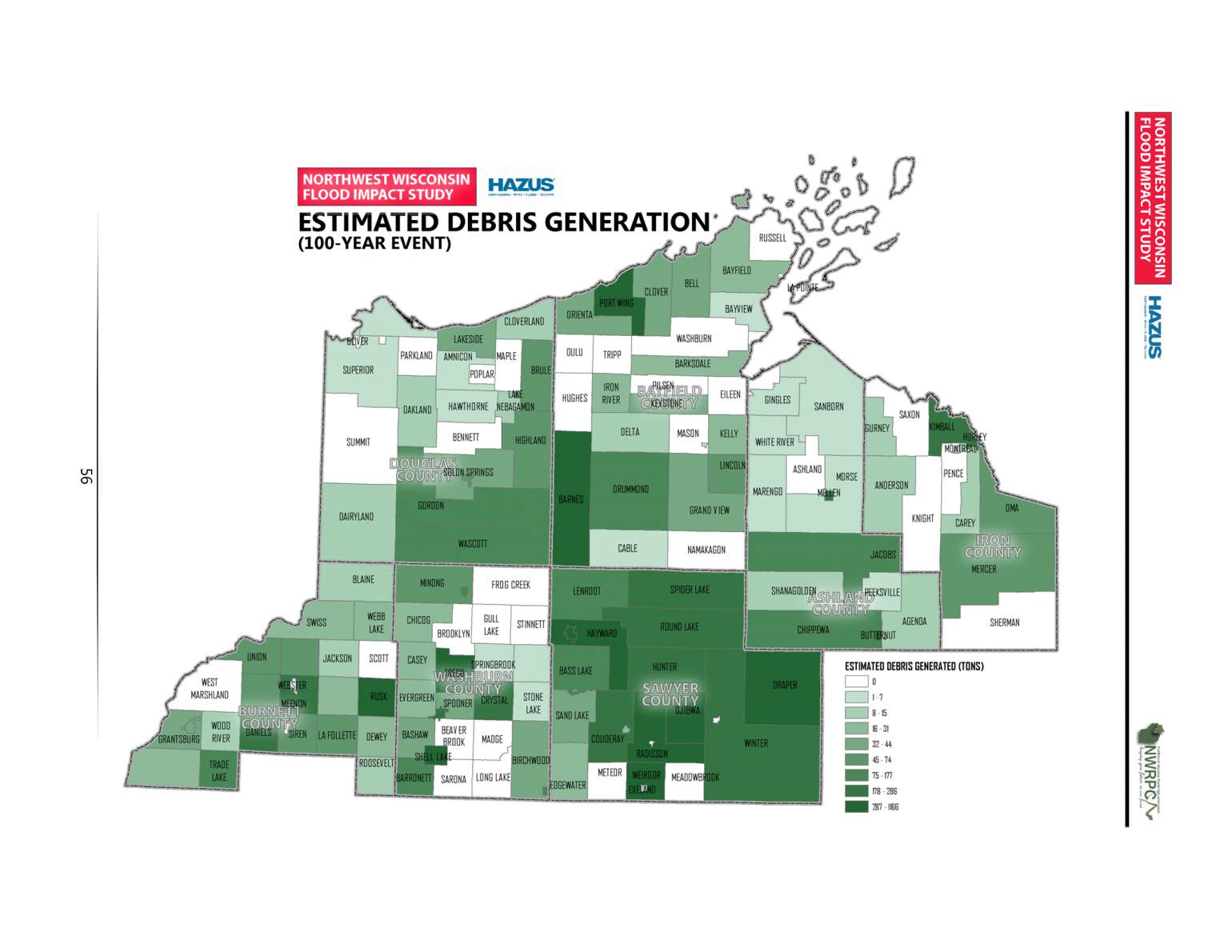

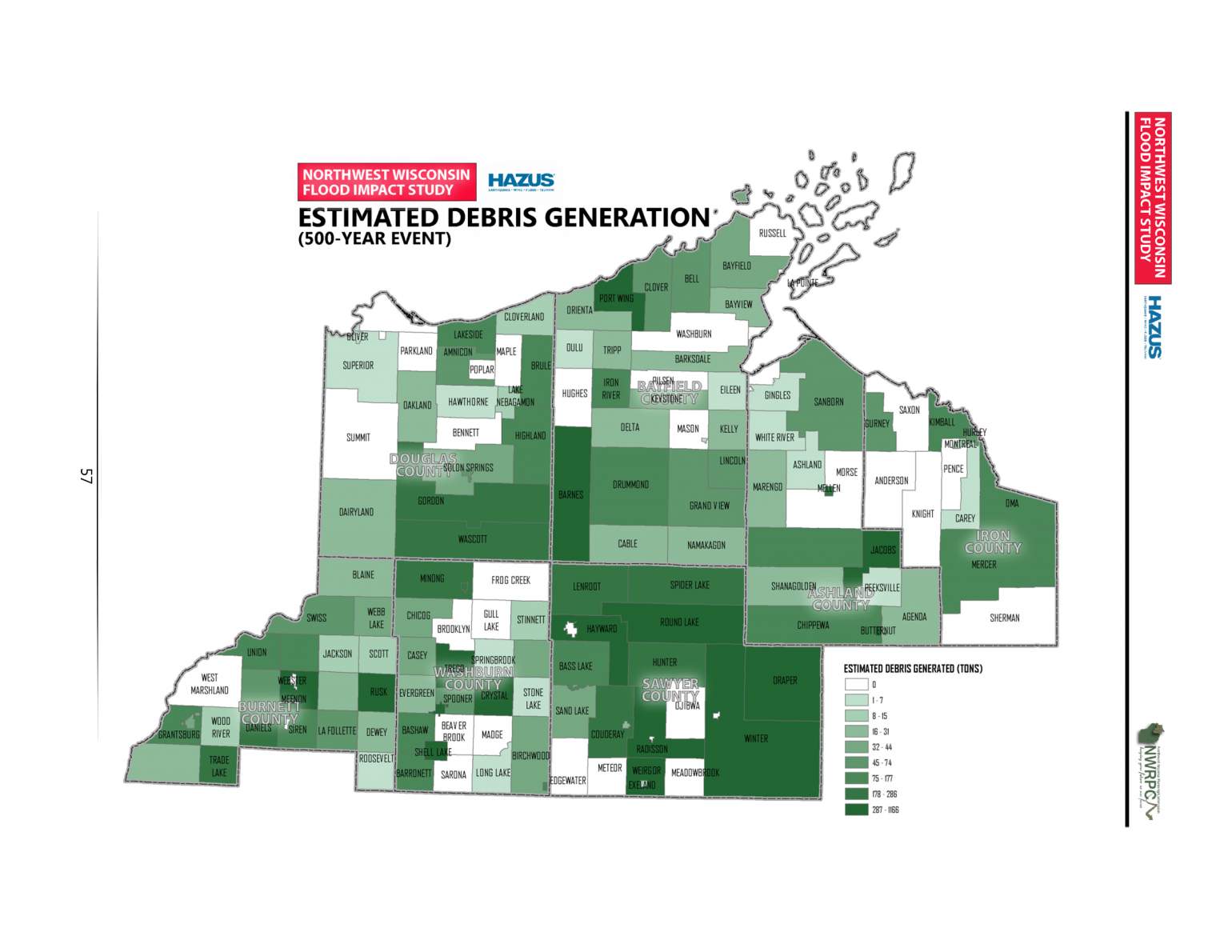

That study came a little more than two years after the 2016 storm that produced extensive flooding in parts of Bayfield, Ashland and Iron counties, to the north and east of Hayward. If the storm system had tracked slightly farther south, losses in Sawyer County likely could have been much higher, according to the study. It estimated that flooding would impact a greater number of buildings, produce more debris and generate higher damage costs in Sawyer County than in any other in the seven-county study region.

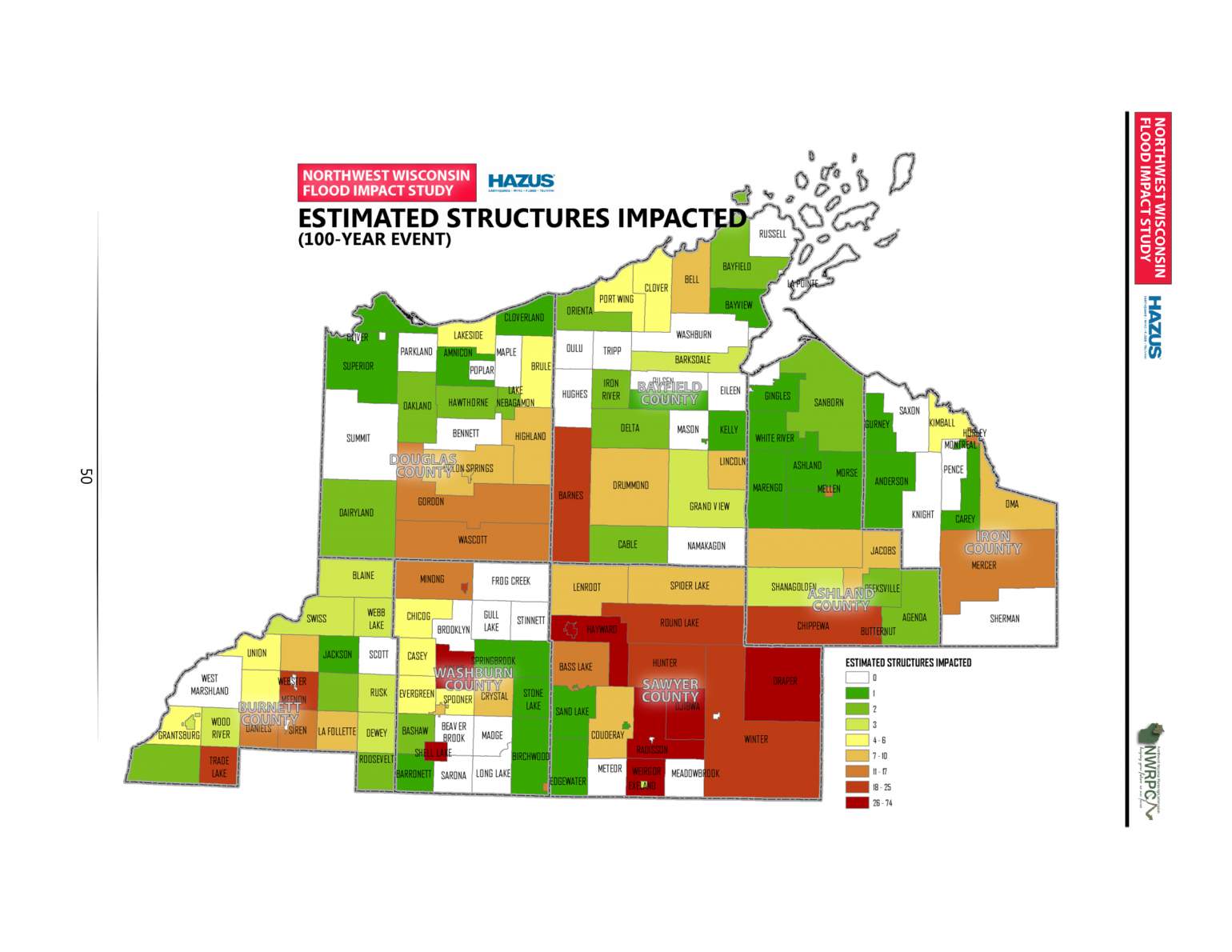

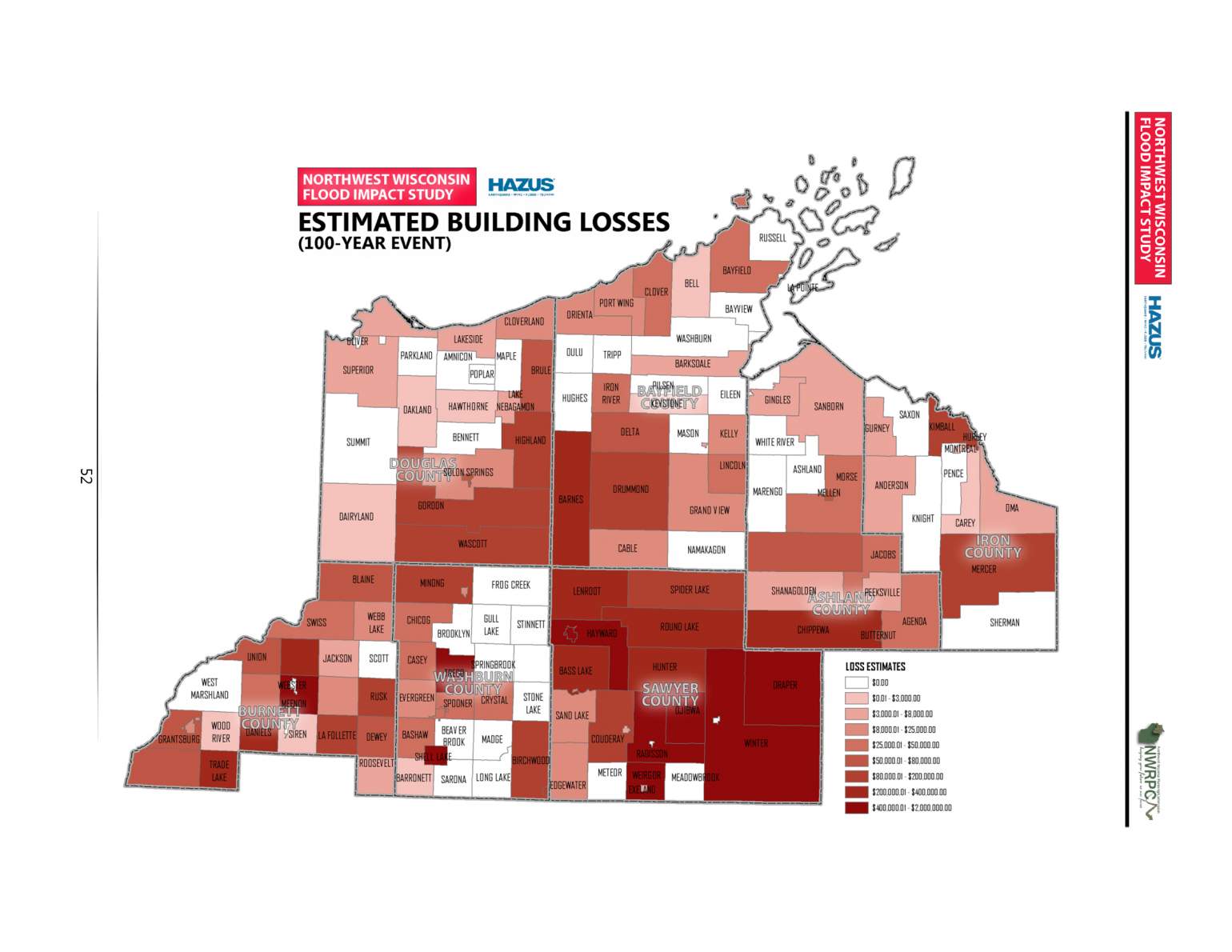

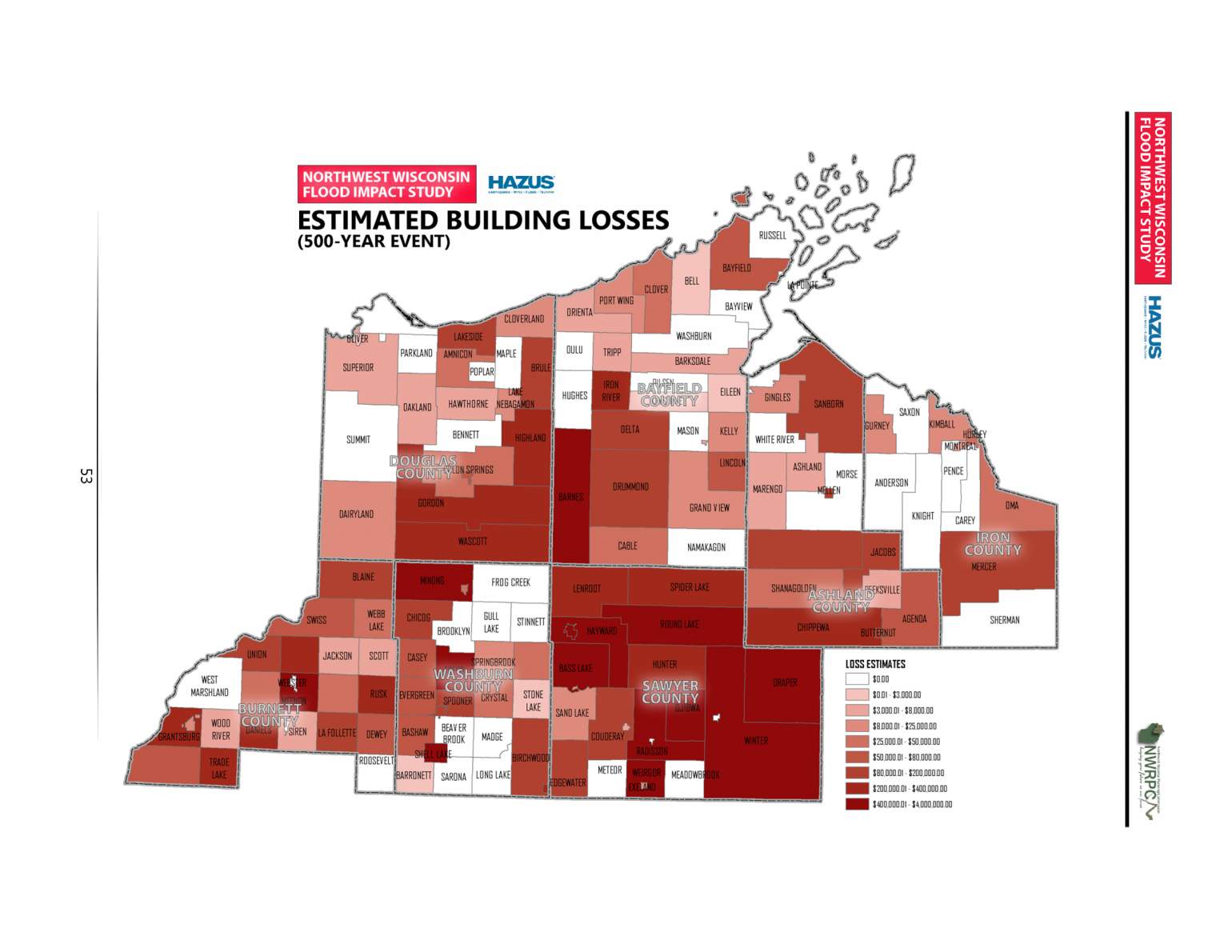

The study utilized Lidar data — highly-detailed information about the land surface collected via aerial surveys — and open-source modeling software from the Federal Emergency Management Agency called Hazus to map the estimated flood impact of large storms across the region. The results show that much of Sawyer County, which is flat and filled with lakes, rivers and swamps, would be inundated following a 100-year or 500-year flood.

For instance, in a 100-year flood — a flood considered to have a 1% chance of occurring in a year — the estimated cost of damage to buildings would be more than $7.6 million. That figure is roughly equal to the estimated costs of flood damage to buildings in the other six counties included in the study combined. The damage estimates from a 500-year flood also show Sawyer County faring far worse than neighboring counties.

The flood-risk study provides a stark warning that local officials are beginning to heed.

In 2019, Sawyer County’s Local Emergency Planning Committee, which Sanchez leads, designated flooding as the county’s top hazard for the first time ever. Prior to several large storms that have hit the region in the 2010s, officials didn’t view flooding as a major risk. Those views are shifting.

Jason Laumann, deputy director of the Northwest Regional Planning Commission, noted that despite increasing awareness, local governments remain unprepared for the high costs of mitigating potential floods.

“Communities, counties have begun to realize that they’re going to have to bear some of the burden for this, especially with the infrastructure costs,” Laumann told Here & Now.

Coming up with funds for mitigation projects is a daunting task for communities.

“I’ve just been told there’s no money, there’s no money, there’s no money,” said Sanchez. “We’ve talked to our political entities and they keep saying write grants. Well, we know how competitive grants are nowadays.”

Residents whose homes sit in areas vulnerable to flooding are also burdened with costs, as well as anxiety. Because groundwater levels in Sawyer County are in many places already high, even a moderate storm can cause basements to flood.

Such storms are “very overwhelming,” said Sandy Okamoto, a Hayward resident who owns one home and rents out another near a small creek that runs through the city. “And all I do is run back and forth between the two houses and move pumps and move hoses.”

High waters also threaten roads and other public infrastructure in and around Hayward. In July 2019, one local road in the town of Hayward was partially underwater even without the impact of a large rainstorm.

“Now that it’s underwater, there’s definitely going to be some structural issues that will have to be addressed,” said Don Hamblin, the fire chief and public works director for the community. He is pursuing efforts to raise roads and upgrade infrastructure like culverts where possible to mitigate high water and flash flooding impacts. Some roads in the township are being regraded nearly a foot higher in places to protect against rising waters.

“We’ve added anywhere between 4 and 10 inches of gravel in some places to get better drainage and improve some of the structure under the road,” Hamblin said.

Like his counterparts in communities across Sawyer County and northwestern Wisconsin, Hamblin is trying to be proactive, but limited resources and uncertainty about what the future holds can make that difficult.

“Do we plan 50 years or 100 years down the road or do we plan for tomorrow and hope for the best?” he asked.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us