Gravity Of Precedent Fuels Challenge To Foxconn's Lake Michigan Bid

Wisconsin's decision to let Foxconn draw water from Lake Michigan may set a precedent for water use that resonates across the Great Lakes region and beyond.

By Scott Gordon

June 19, 2018

Aerial view of Lake Michigan shoreline

Wisconsin’s decision to let Foxconn draw water from Lake Michigan may set a precedent for water use that resonates across the Great Lakes region and beyond. But an emerging challenge to it is really a battle over how to interpret the Great Lakes Compact, the 10-years-young eight-state agreement that governs access to one of the world’s most voluminous supplies of freshwater.

Madison-based law firm Midwest Environmental Advocates is leading a challenge. Instead of going straight to court, the firm and a coalition of Wisconsin- and Minnesota-based environmental groups it represents have appealed the matter to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, which approved the diversion in April 2018 and has decided to hear the appeal. An administrative law judge will be assigned to the case and set a schedule for hearings; if the challengers aren’t happy with the administrative law judge’s eventual decision, they can then file a lawsuit in state circuit court.

However, the specific language of the Compact has ambiguities that are at the source of the dispute over the diversion to serve a factory the Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer is building. It states that diverted water “shall be used solely for Public Water Supply Purposes.” The language goes on to define “Public Water Supply Purposes” as “water distributed to the public through a physically connected system of treatment, storage and distribution facilities serving a group of largely residential customers that may also serve industrial, commercial, and other institutional operators.”

The Compact specifies that industrial users can have access to diverted water — and it’s routine for businesses to buy water from public utilities — but that water must “largely” supply residential customers to drink, bathe in, cook with and so on. The dispute over the diversion intended to supply Foxconn comes down to how flexible the term “Public Water Supply Purposes” is, and in what context “largely” is used.

The Racine Water Utility is the utility that submitted the diversion application to source additional Lake Michigan water to supply Foxconn. In asking the DNR to allow a diversion, utility made it clear that all the water it wants to pump across the Great Lakes Basin’s boundary — up to 7 million gallons per day — will go toward the massive manufacturing complex and related adjacent businesses. Neither the utility nor any of the diversion’s supporters are claiming that one drop of that water will be going into someone’s home.

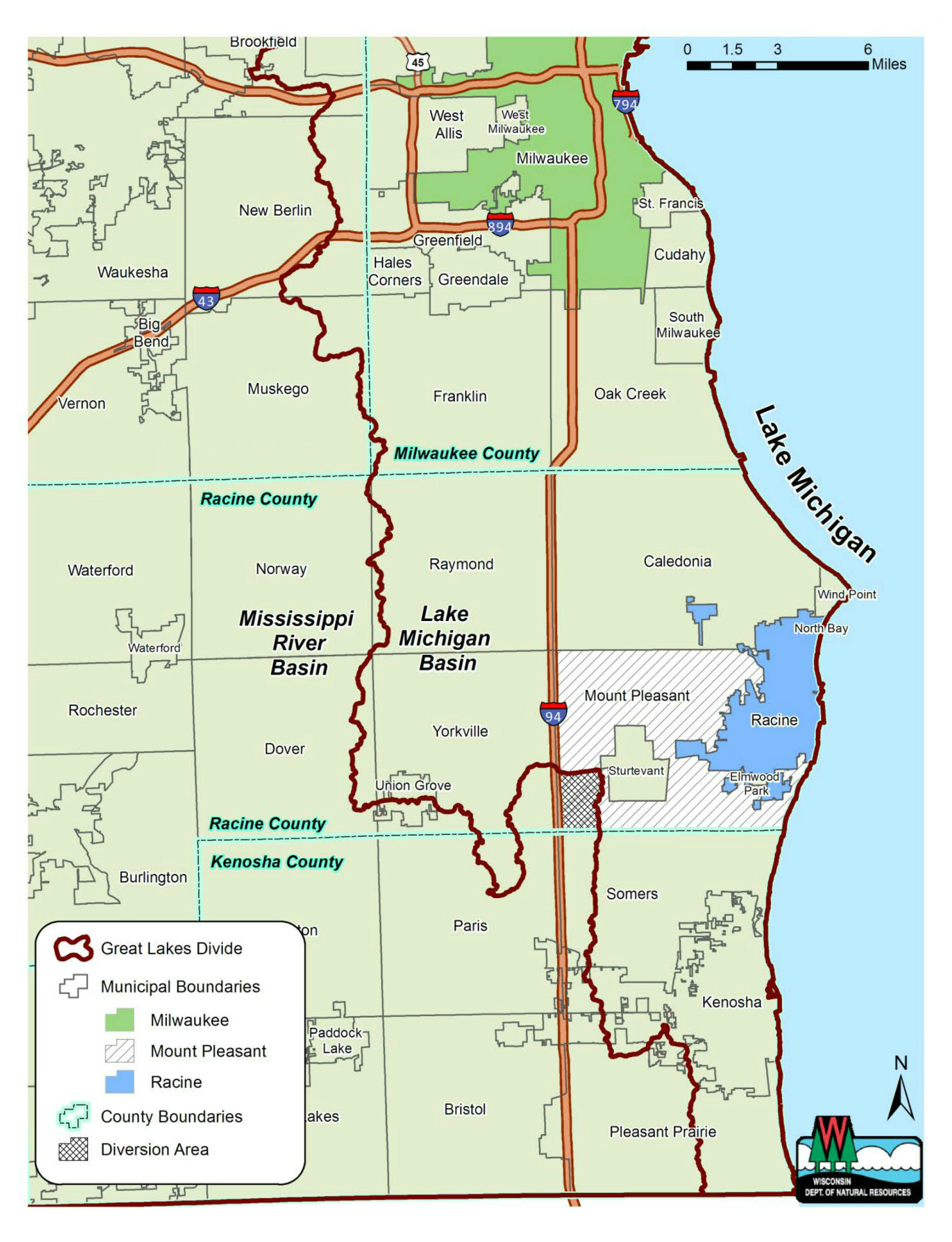

Foxconn will use the diverted water in the village of Mount Pleasant, a municipality that is located partly in and partly out of the Basin; to use Lake Michigan water outside its boundary, Racine’s water utility needs state-level approval pursuant to the Compact. Racine officials assert that this planned use qualifies as “Public Water Supply Purposes” because even if it’s sending millions of gallons to the Foxconn factory, the utility’s service area as a whole will still be largely residential. That argument treats water used inside and outside of the Great Lakes Basin as one big aggregate, and the DNR cited that rationale in its approval.

The question at issue in the challenge, then, is in order for a diversion to qualify as “Public Water Supply Purposes,” does the diversion area itself have to be largely residential, or is it satisfactory for a utility to make big withdrawals for industrial purposes outside the Basin so long as it’s selling more water to residential households overall? The Great Lakes Compact doesn’t say one way or another.

Also, exactly what does “largely residential customers” mean? Is there a specific level or percentage that qualifies, or some cutoff where industrial water use is considered too much? It’s not in the text of the Compact. And since the agreement was ratified in 2008, there hasn’t been much opportunity for state or federal courts to parse how the language should be applied. The Compact’s text is less than 30 pages long — a beach read, in legal terms.

The ongoing tussle over the Foxconn diversion might be the first real chance to formulate answers to these gray areas — or perhaps just plain blank spaces on the legal map.

In a June 8, 2018 interviewwith Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now, Midwest Environmental Advocates attorney Jimmy Parra asserted that the Compact’s language doesn’t cover the Foxconn diversion.

“I think on a sort of common-sense level, most people have a sense of what that means, and it’s not to send water to one private industrial customer for their exclusive use,” Parra said. “The city of Racine and all the residential users that it currently serves are in the Great Lakes Basin. And what we think the Compact says is you have to look at the area outside of the Basin, and look at the area where the water’s being sent.”

Here & Now invited the DNR to share its perspective about the diversion, but the agency declined to issue a statement or provide an official to be interviewed. In a statement to Here & Now, Racine Mayor Cory Mason affirmed the DNR’s interpretation of the Compact’s language on “Public Water Supply Purposes.”

“Racine’s water utility certainly meets that definition and would continue to meet that definition if the small part of [Mount Pleasant] outside the Basin were served with Great Lakes water,” said Mason.

Meanwhile, Parra and the law firm base their argument on the Great Lakes Compact’s requirements for diversions that specifically states “all the Water so transferred shall be used solely for Public Water Supply Purposes within the Straddling Community.” That language suggests that when sussing out how “public” a diversion is, the state should simply consider the specific area served by the diversion.

Since the Compact was ratified, only two other parties have applied for diversions. The Milwaukee suburb of New Berlin, which straddles the basin line, received DNR approval in 2009 to use Lake Michigan water. The city of Waukesha, which is located wholly outside the Great Lakes Basin but can apply for water access under certain terms because it’s in a county that straddles its boundary, had to seek the unanimous consent of the governors of the eight Great Lakes states, and got it in 2016. (Some terms of the Compact requires the involvement of a regional body where each state has a voice, but much of its enforcement is left to to state-level regulators.)

Both New Berlin and Waukesha sought drinking water for residential users first and foremost. Waukesha’s bid for Lake Michigan water has been controversial for a variety of reasons, but its opponents are not saying the city is making a massive water grab on behalf of a single company.

Parra told WisContext in a phone interview that the New Berlin and Waukesha diversions provide an example of how “Public Water Supply Purposes” language of the Compact should be applied, and noted they may bolster the argument that the reasoning behind the Foxconn diversion approval misinterprets it. The way the DNR currently interprets the Compact, he told Here & Now, opens the door for industrial users outside the Great Lakes Basin to take advantage.

“In Minnesota there’s a number of mines or mineral deposits that are close to the Basin line in the Iron Range,” he said. “Under the Wisconsin DNR’s interpretation, it’s possible that Great Lakes water could now be used to supply that very water-intensive industry. It’s not this project, it’s what comes next.”

The 7 million gallons Foxconn and Racine are asking for is indeed a lot of water, though not very much relative to the Great Lakes as a whole. But it’s the longer-term significance of the diversion that is at the heart of this debate. What kind of precedent would the Foxconn diversion set, and how that will affect the Great Lakes as a freshwater resource over the long run? What if more industrial users set up operations in Great Lakes states with an eye toward using that water?

Several of Wisconsin’s fellow Great Lakes states have raised concerns and questions about the Foxconn diversion, though none have yet launched a formal effort to block it. But the entire region will be affected by the outcome, as states and local communities contemplate the future role of water resources in their economies

Passport

Passport

Follow Us