Foxconn Taps Into The Plenitude And Perils Of Great Lakes Water

Cities and businesses seeking to access Great Lakes waters often emphasize how minuscule their water use would be compared to even the supply of just one of the individual lakes.

By Scott Gordon

April 11, 2018

Wave striking boulders on south shore of Lake Superior

Cities and businesses seeking to access Great Lakes waters often emphasize how minuscule their water use would be compared to even the supply of just one of the individual lakes. Officials in Waukesha have likened their plan to use Lake Michigan as a water source to taking a thimble-full of water from an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

In terms of overall volume, these assertions are on point. Hydrologists studying the Great Lakes point out that humans’ current withdrawals of water is a much smaller factor in terms of volume than the cycles of precipitation and evaporation at work across the region.

The vastness of this water resource, not to mention a few billion dollars in publicly funded incentives, helped entice Taiwan-based electronics manufacturer Foxconn to build an LCD screen factory complex in the village of Mount Pleasant, located just southwest of Racine. Fabricating electronics is a process that requires copious amounts of water, and the company, through the city of Racine, has proposed withdrawing about 7 million gallons per day from Lake Michigan. As detailed in the city’s permit application, Foxconn expects a consumptive water use of 39 percent, which means returning just 61 percent of the water volume it takes out of the Great Lakes watershed.

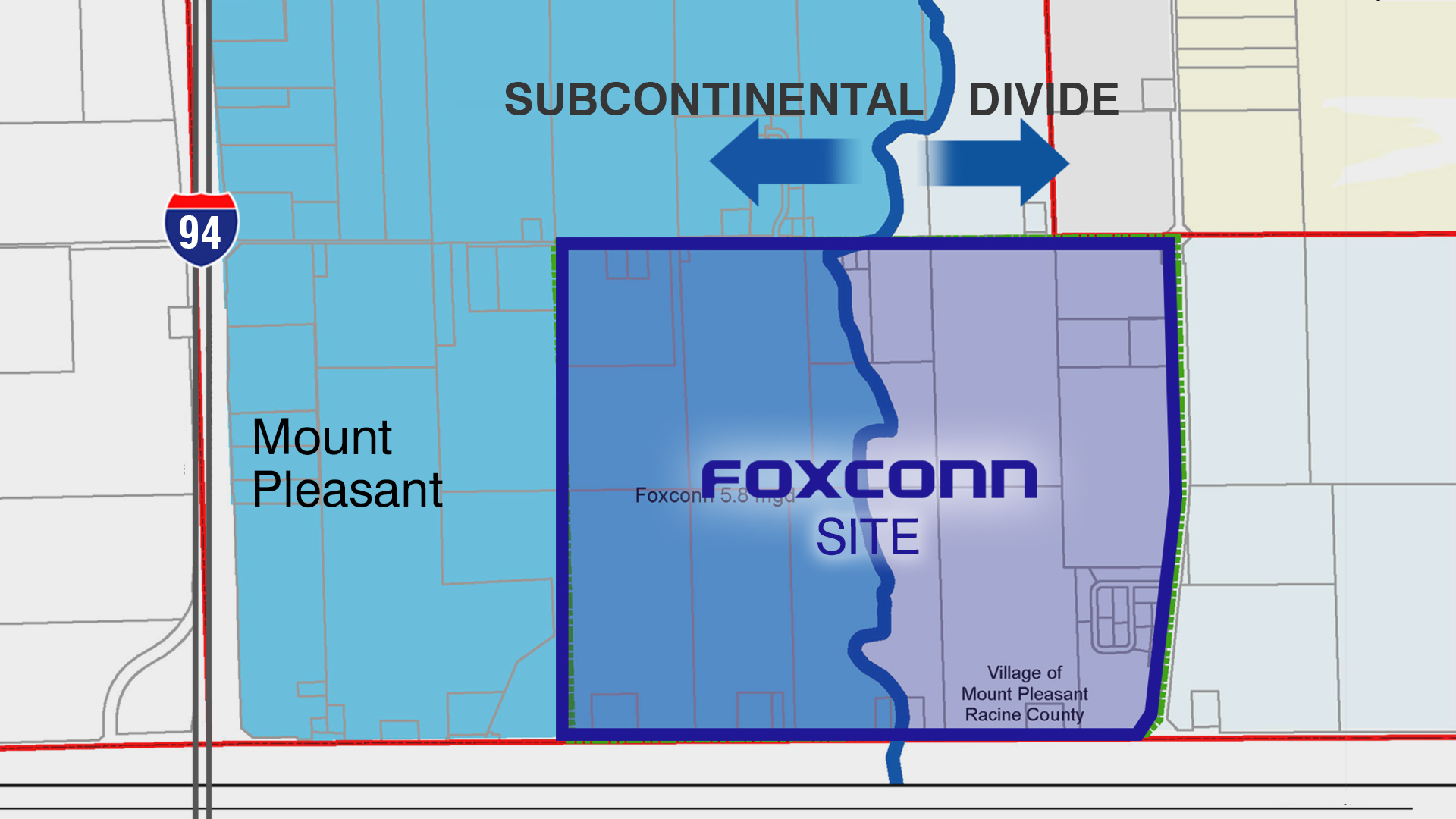

The laws and regulations Foxconn will have to follow have everything to do with where its operation sits relative to the part-hydrological, part-political line that defines the Great Lakes Basin. A legally binding eight-state agreement known as the Great Lake Compact lays out the terms of access to water for different parties, depending on whether they’re located wholly within the Basin, outside of it, or partially in and partially out.

The Foxconn plant’s proposed site and the community it’s located within each straddle the basin line. Given this location, Mount Pleasant is therefore entitled to use Lake Michigan water — which it already obtains through an agreement with the Racine Water Utility— provided that it discharges water back into the basin.

For Foxconn to access the water as a customer of Racine, it must to make a case to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, as part of a permitting process the state is required to undertake as a party to the Compact. While there’s vocal public opposition to Foxconn’s water plan, and a few possible legal hurdles, the Wisconsin Legislature and Gov. Scott Walker are generally in favor of fast-tracking the Foxconn deal process, and the DNR faces political pressure to make business-friendly decisions.

Racine’s water utility doesn’t keep track of consumptive use among its 40 or so industrial users, said administrator Keith Haas. He declined to say whether or not Foxconn’s proposed consumptive use sounded unusually high.

Steve Cole, who was until recently a spokesperson for the Great Lakes Commission, an agency that promotes cooperation among the eight states and two Canadian provinces in the Great Lakes Basin, thinks it’s an outlier. (After speaking with WisContext, he departed the Commission for another job.)

“That’s substantially higher than a normal industrial use,” Cole said in March 2018. “Typically industrial users tend to be in the 10 to 15 percent range, and that’s pretty high.”

Consumptive use, conservation trade-offs

Under the Great Lakes Compact, people withdraw Great Lakes water with the understanding that it’s staying within the Great Lakes Basin, though there are some caveats.

When a municipal water utility sources the lakes for drinking water, it’s discharging treated wastewater back into the lakes, or to streams and rivers that ultimately flow into them. When farmers use Great Lakes water for irrigation, they aren’t allowed to spread it on fields that sit outside the Basin. And so forth. In public environmental and policy discussions, these practices often get reduced to a shorthand that could understandably make someone think that the cities and businesses drawing water from the lakes are promising to send it all back. But anyone who’s watched water boil knows that’s not true.

Much of the water used for drinking, cooking, bathing, cleaning or industrial processes can be recovered and sent back to its source after being treated to clean up at least some of the contaminants the water mingles with along the way. Some of the water used for irrigation will seep back down into groundwater, which ultimately has some interchange with surface waters in the Basin. But plenty of that water will evaporate, and be absorbed into crops and industrial products that won’t all remain inside the Basin. Communities and industries who use the water will often state that they’re returning it all, “minus consumptive use.”

The Great Lakes Compact itself specifies that “All Water Withdrawn from the Basin shall be returned, either naturally or after use, to the Source Watershed less an allowance for Consumptive Use.” If a user is within the Basin, that allowance can be quite a lot. The language of the Compact doesn’t ultimately indicate how much consumptive use is too much, either in terms of sheer volume or as a percentage of the water volume a given user withdraws. If a user proposes increasing its consumptive use by 5 million gallons or more per day, that triggers a regional review process under the Compact’s terms, but that review doesn’t lead to any binding requirements.

In fact, a big industrial user in the Great Lakes Basin that buys water from a public water utility could in theory discharge none of it back, said Racine water utility manager Keith Haas. It sounds bold, but the language of the Great Lakes Compact doesn’t offer any specific numbers that say how much consumptive use it too much. (It does broadly call for efficient water use and conservation, though.)

When one just takes into account the volume of water withdrawn from Lake Michigan, Racine isn’t even close to pushing it. Even when it adds 7 million gallons per day for Foxconn to all the other water it draws from the lake for its other residential and industrial customers, Racine will be comfortably within the total amount it’s allowed to draw, 60 million gallons per day.

Haas isn’t particularly concerned about what would happen if Racine exceeded that 60 million gallon threshold one day, or even if it engaged in a diversion that exceeded the threshold of 5 million gallons per day of new consumptive use. At that point, he said, Racine would have to come up with a water-conservation plan, but wouldn’t necessarily be barred from using the water it wanted to.

“You can still get the water, you just have to make it onerous on every other ratepayer in the area,” Haas said.

In the case of the Foxconn diversion, Haas will have to track what volume of water the factory ends up withdrawing and sends back for treatment, and prepare reports on its consumptive use. But when it comes to Racine’s customers located within the Great Lakes Basin, that isn’t something the utility has to keep track of.

“I really have no statistics that I could measure anybody right now on a delta of what they use and what they discharge,” he said.

Haas believes the 7 million gallons Foxconn is asking for is “a drop in the bucket,” and has stressed to WisContext and other media outlets that if the factory were built just a little more to the east, the Racine Water Utility wouldn’t have to think much about the Great Lakes Compact. Running a utility that used to serve far more industrial customers than it does now, and in an era where households use water more efficiently than they previously did, Haas does not feel that Foxconn’s use would burdening the Great Lakes watershed.

“The people in my industry are in the business to sell water, especially in the Great Lakes, and many of us used to sell a lot more water than what we sell today,” he said.

In its application for water access, Foxconn has stressed that it will recycle water within the factory in order to use it more efficiently. At one point in the application process, Foxconn claims that its water recycling technology would reduce the plant’s potential water needs by a factor of about 15 million gallons per day, meaning they would theoretically need to ask more if not for that efficiency. That’s a big claim, but it may actually be credible.

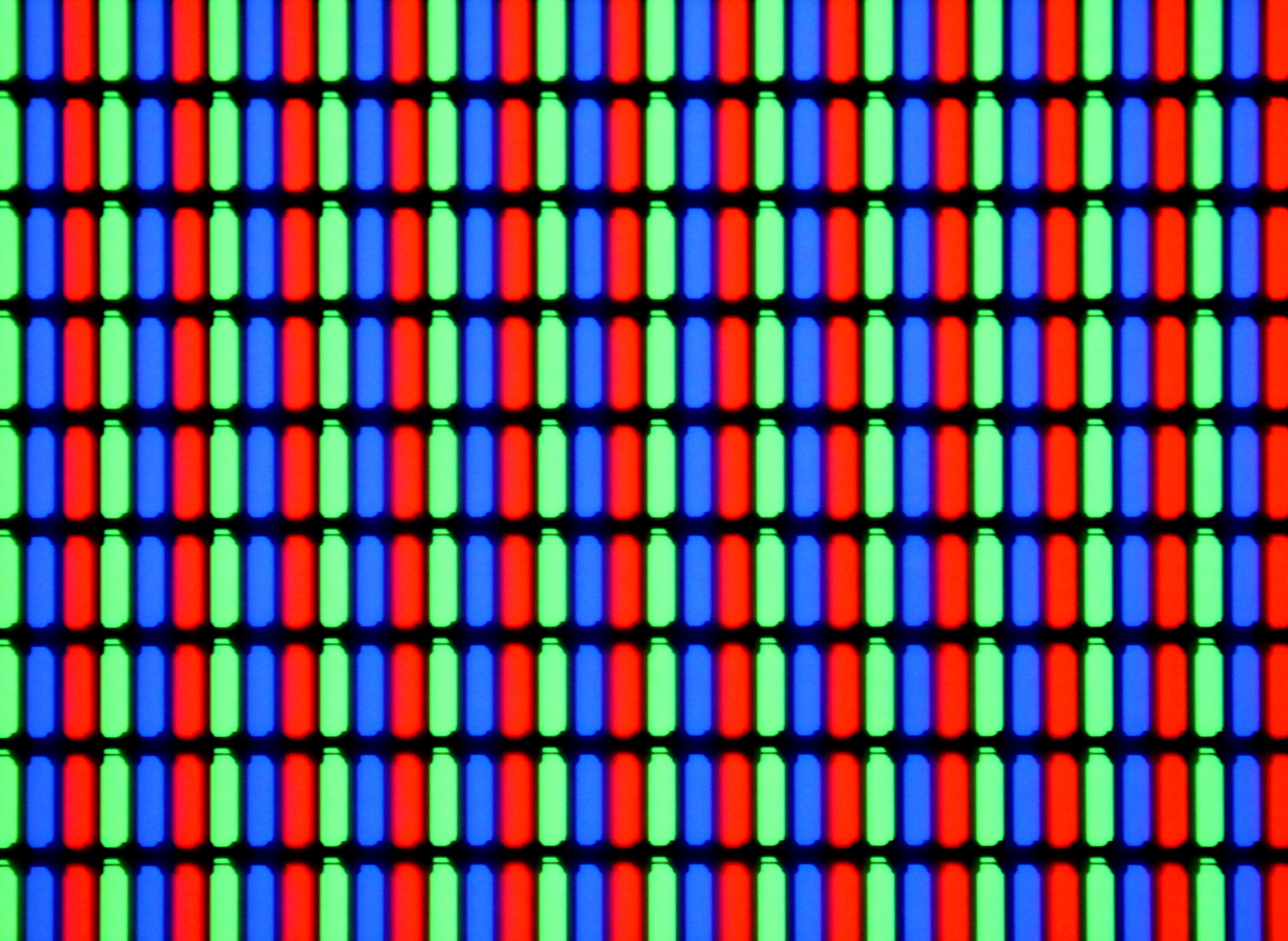

Mengshan Lee, a professor of safety, health and environmental engineering at National Kaohsiung First University of Science and Technology in Taiwan, has studied water-recycling technology in electronics manufacturing. While making electronics is extraordinarily water-intensive, because many fine components have to be cleaned over and over again as they’re fabricated and assembled, it’s not quite like making, say, canned vegetables, where some of that water becomes part of the product shipped out of the factory.

“In general, electronic manufacturing process involve intensive ‘water use’ rather than ‘water consumption,'” Lee said. “In other words, as the electronic products do not contain water, the whole manufacturing process should not consume too much water. Most of the water use at an electronic fab is for rinsing at the processing stage. Another major water use point is for cooling towers.”

Different kinds of filters and chemical processes can enable an electronics factory to use and reuse water for cleaning components. However, Lee cautions that intensive water recycling does not in and of itself guarantee a net environmental benefit, because these processes can also use a lot of energy.

Racine’s water utility doesn’t yet know exactly what kind of equipment or techniques Foxconn will use to recycle water. Haas said the company’s engineers have presented him with eight or nine possible plans, and the utility will need to inspect and approve whatever water systems Foxconn does end up using.

Foxconn will also have to do some “pre-treatment” on the wastewater it discharges — that is, any necessary treatment that Racine’s wastewater treatment plant can’t provide, like removing certain heavy metals used in the electronics manufacturing process. There are federal pre-treatment standards, but Haas said that part of the process is mostly regulated by local water utilities. But due to the high-profile nature of the Foxconn project, he said state regulators might look over his shoulder and advise him on the company’s pre-treatment permit.

Withdrawals from a massive budget

All in all, the Great Lakes contain about 6 quadrillion gallons of freshwater. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that people withdraw about 56 billion gallons per day. That’s roughly 0.000933 percent of the lakes’ total volume. Just about everyone contacted by WisContext about this issue — including environmental scientists and water-utility managers — acknowledges that cycles of evaporation and precipitation have a vastly greater influence on Great Lakes water levels than human withdrawals.

Water comes into the lakes from thousands of connecting streams and rivers in the Great Lakes Basin and groundwater within it human wastewater discharges, rainwater and snowmelt running off the land, and rain and snow falling on the lakes themselves.

A few human-made diversions play into the system as well. The Ogoki River in Ontario was diverted into the Great Lakes Basin in the 1940s as part of a hydropower project. The water the Ogoki diversion brings into Lake Superior more than offsets the hefty amount of water the infamous Chicago River diversion carries out of Lake Michigan and into the Mississippi River watershed.

American and Canadian authorities have built complex systems of locks at many points throughout the watershed over the years, in efforts to make the lakes an economically powerful shipping corridor connected to the Atlantic Ocean. This infrastructure can impact overall lake levels as well.

Practically since heavy European settlement and urbanized development began in the region, Great Lakes water politics have revolved around fears of outsiders making off with their waters, from a Canadian entrepreneur’s failed scheme to ship tankers full of water for customers in Asia to ongoing talk about piping supplies to the American Southwest.

Water levels on each of the Great Lakes except Superior are lower than they were in 1860, the earliest year for which NOAA provides annual averages. Between 1860 and 2015, annual averages (expressed as meters above sea level) on the lakes have varied within a margin of a meter or two. That margin of variation appears to be largest on Michigan-Huron, which are at the same elevation and hydrologically a single lake, where the highest level of 177.39 meters was recorded in 1886 and the lowest of 175.68 meters was recorded in 1964.

Lake levels have actually trended upwards since the turn of the century, so while the water budget, as hydrologists call it, is not at record highs, it’s not necessarily being depleted either. The Great Lakes still face an array of ecological challenges, from human-caused phosphorus pollution to invasive species destabilizing the food web, aside from considerations of sheer water quantity.

Evaporation and precipitation play crucial roles in any body of surface water, but are especially powerful forces on the Great Lakes because they have such a broad surface area that’s exposed to these process.

“I think the typical inland lake, maybe a 10th of its drainage area is actual water, and for some of the Great Lakes it’s a lot bigger than that, a quarter to a third,” said Anne Clites, an Ann Arbor-based scientist with NOAA. “It’s a very unusual system because we have so much surface open water.”

The climate question mark

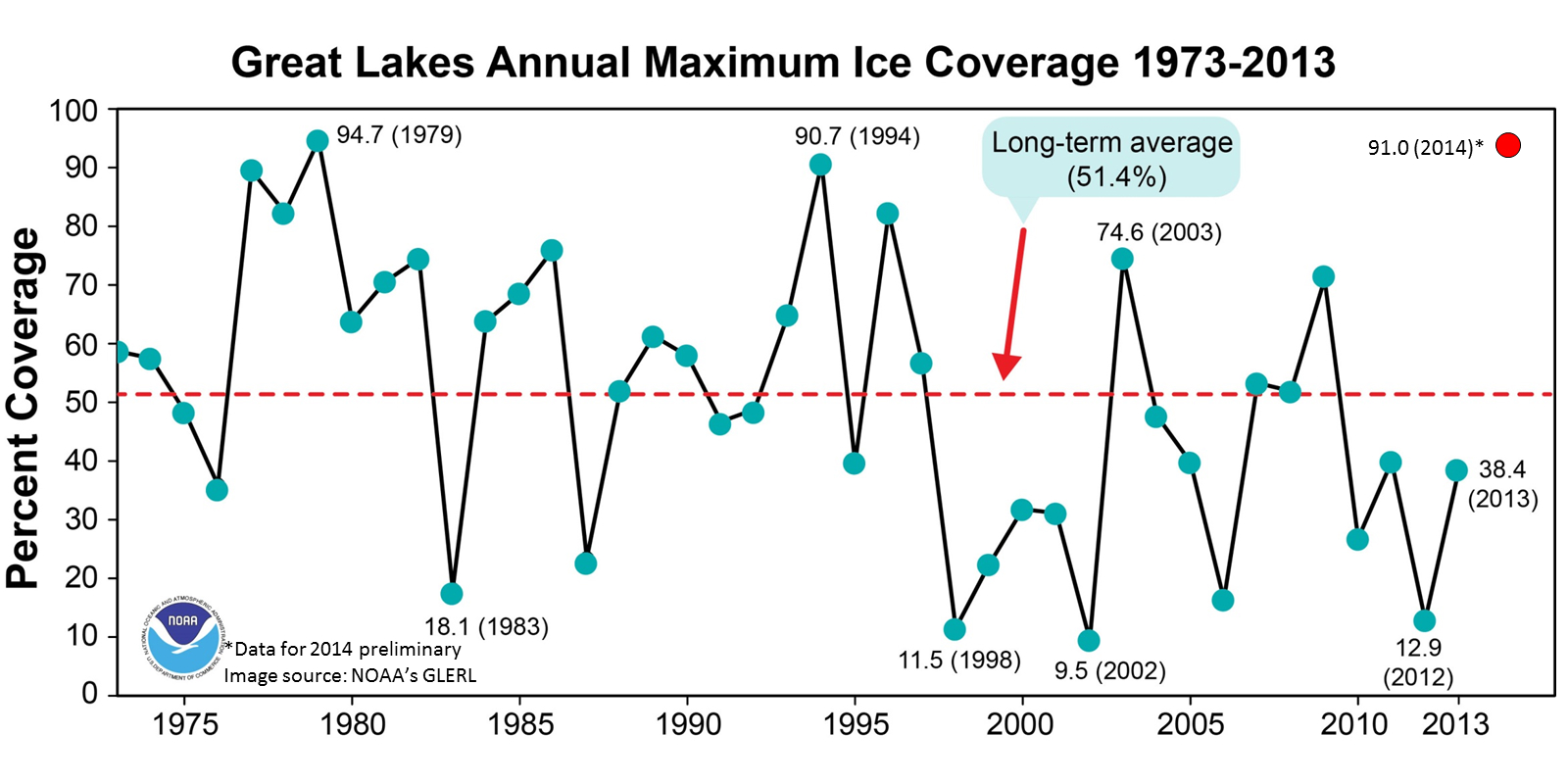

The expansive surface area of the Great Lakes also plays a role in how they’ll respond to a warming planetary climate, which is changing the natural cycles that impact water levels. Water temperatures in the Great Lakes are increasing faster than global air and ocean temperatures, and Lake Superior — the biggest, deepest and most upstream of the Great Lakes — is one of the fastest-warming lakes in the world. Warmer overall temperatures (especially low temperatures that aren’t as low) means winter ice covers a smaller area of the lakes’ surfaces and for shorter periods of time. This drop in ice cover in turn exposes a greater area of the lakes to evaporation in dry winter air.

At the same time, climatologists project that a warmer global climate will mean more precipitation, and more frequent and intense storms, in the Midwest. As Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reporter Dan Egan points out in his 2017 book The Death And Life Of The Great Lakes, it’s not year clear whether increased levels of evaporation and precipitation will balance each other out. Regardless of the impact on water quantity, though, an increase in severe rainstorms is definitely bad news for water quality, as heavier precipitation will accelerate the process of washing farm fertilizer and other pollutants into the lakes from the vast swaths of agricultural land and urban areas lining their shores.

If climate change destabilizes the cycle of evaporation and precipitation in the Great Lakes, it’s possible that human water withdrawals could have a more significant impact on the watershed overall. A large industrial operation like Foxconn, in addition to creating a major new source of air pollution, can itself impact climate change. Its intensive energy needs would almost certainly increase Wisconsin’s greenhouse-gas footprint.

Foxconn CEO Terry Gou has touted his interest in clean energy in recent years, has invested in solar energy, and could very well build some of its own renewable energy infrastructure onsite. However, if the plant’s power comes from Wisconsin’s existing electricity grid, a lot of it is coming from coal and natural gas. Southern Wisconsin does have some biomass power plants, but the overwhelming majority of power generation capacity in the area is likewise from coal and natural gas. Moreover, electronics manufacturing can also directly contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Foxconn won’t be the last major industrial water user that sees promise in the plenitude of the Great Lakes, nor will Wisconsin be the last willing to provide subsidies and environmental exemptions. No matter how massive the lakes are, the demand from within and outside of the region, combined with the environmental fallout of other human activities, will continue to pose challenges.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us