Federal, state, local government agencies navigate an increasingly fractured social media landscape

Rising levels of disinformation and growing concerns over the mental health impacts of social media is prompting communicators at different levels of government to reconsider how they use different platforms to share updates with the public.

March 21, 2024

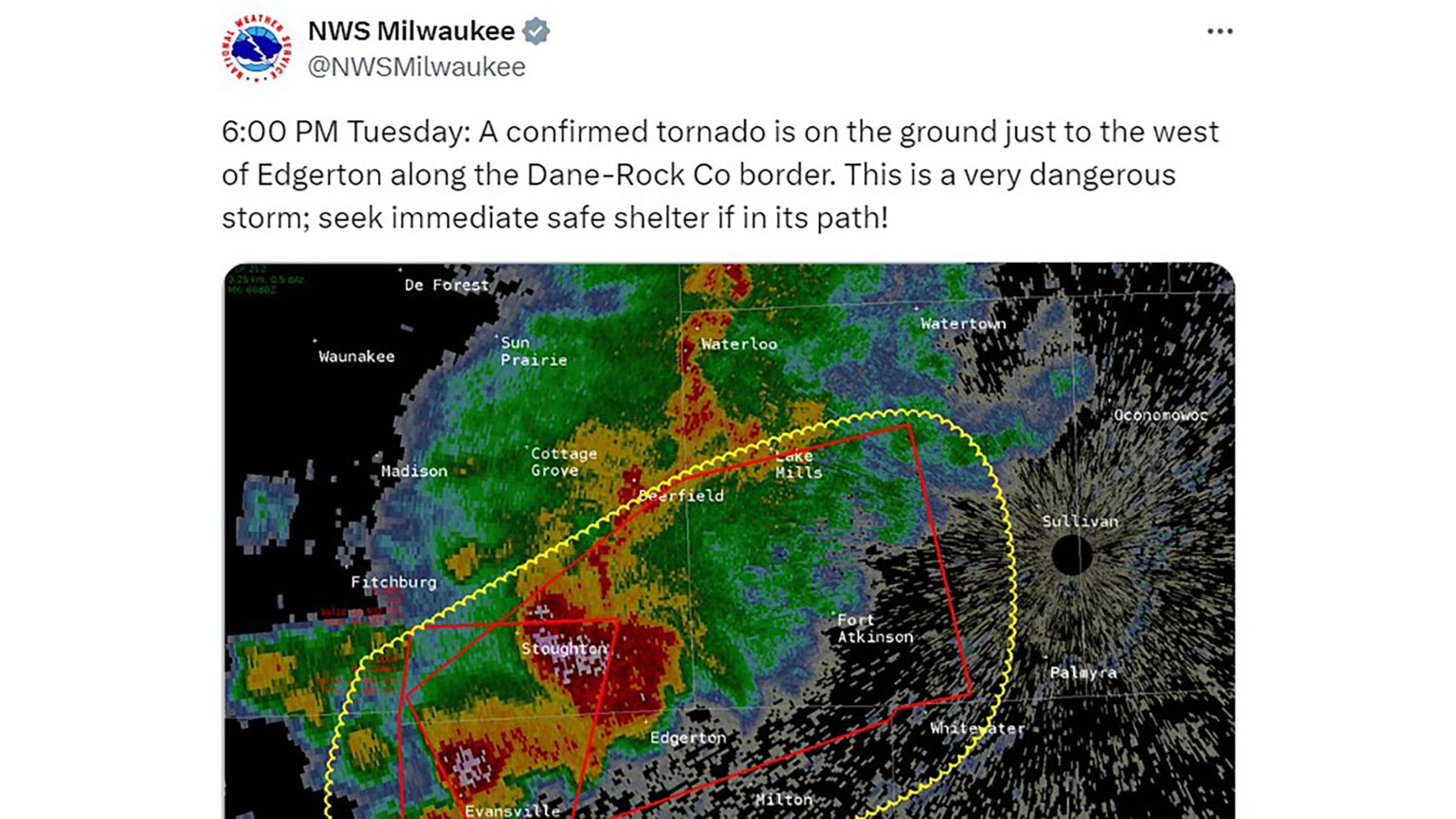

At 6:03 p.m. on Feb. 8, 2024, the Milwaukee/Sullivan office of the National Weather Service posted an update to "X" about a confirmed tornado it was tracking in southern Wisconsin. This tornado was the first ever recorded in the state during the month of February. (Source: National Weather Service Forecast Office Milwaukee/Sullivan / "X")

Wisconsin meteorologists closely tracked an historic weather event in early February, when the first tornadoes ever recorded during that month in the state blew across sections of several southern counties. Over the course of that day, the National Weather Service’s Milwaukee/Sullivan office posted nearly four dozen updates on its “X” account, the social media platform formerly known as Twitter.

NWS offices have stayed busy forecasting and issuing updates about weather conditions across Wisconsin in 2024 already, from the state’s first recorded tornado in February to the few instances of major snowfalls over the otherwise mild winter. Day in, day out, updates on all types of weather events and warnings are posted by the NWS on social media platforms like “X,” Facebook, and Instagram.

“We found Facebook gives us the largest reach. But, Twitter traditionally was designed for more of the kind of fast-paced, breaking news kind of information outlets, where we post the majority of our updates — the quick updates,” said Mike Kurz, the warning coordination meteorologist at the NWS La Crosse office.

NWS offices have courted online engagement, noting more people relying on social media for weather updates and information since around 2017 when they began utilizing these platforms more often.

“Twitter feeds are a supplemental service provided by NWS to extend the reach of NWS information. Twitter feeds and tweets do not always reflect the most current information for forecasts, watches, and warnings,” notes the agency in an explanation of how it uses the platform.

There has been especially strong engagement with younger audiences.

“It’s just a tool for us to be able to directly reach people. Weather [services] before social media really didn’t have a direct way to communicate with people,” said Tim Halbach, the warning coordination meteorologist at the Milwaukee/Sullivan office. “But Facebook and ‘X’ are great ways for us to be able to directly communicate with the people that we serve here.”

But while major weather events circulate in the atmosphere, other messages also regularly circulate on social media platforms: false weather models.

“We, as an agency, find ourselves more frequently trying to counteract weather misinformation that we see out there that could potentially lead to confusion or maybe even jeopardize public safety,” said Kurz.

As social media users anticipate approaching weather, many interact and engage with information that isn’t necessarily reliable or offer predictions earlier than accurate data can provide.

Kurz described how what he called “weather enthusiasts” — or accounts dedicated to tracking and predicting weather systems — often share inaccurate data that can confuse and mislead people, whether or not any harm is intended.

“Anybody can start up one of these weather accounts on Facebook and say they’re a weather expert, but oftentimes, they’re not even a degreed meteorologist with training and background in understanding the models,” he said.

Kurz emphasized that when misinformation circulates during severe weather seasons, it can “cause people’s anxiety to rise quickly.”

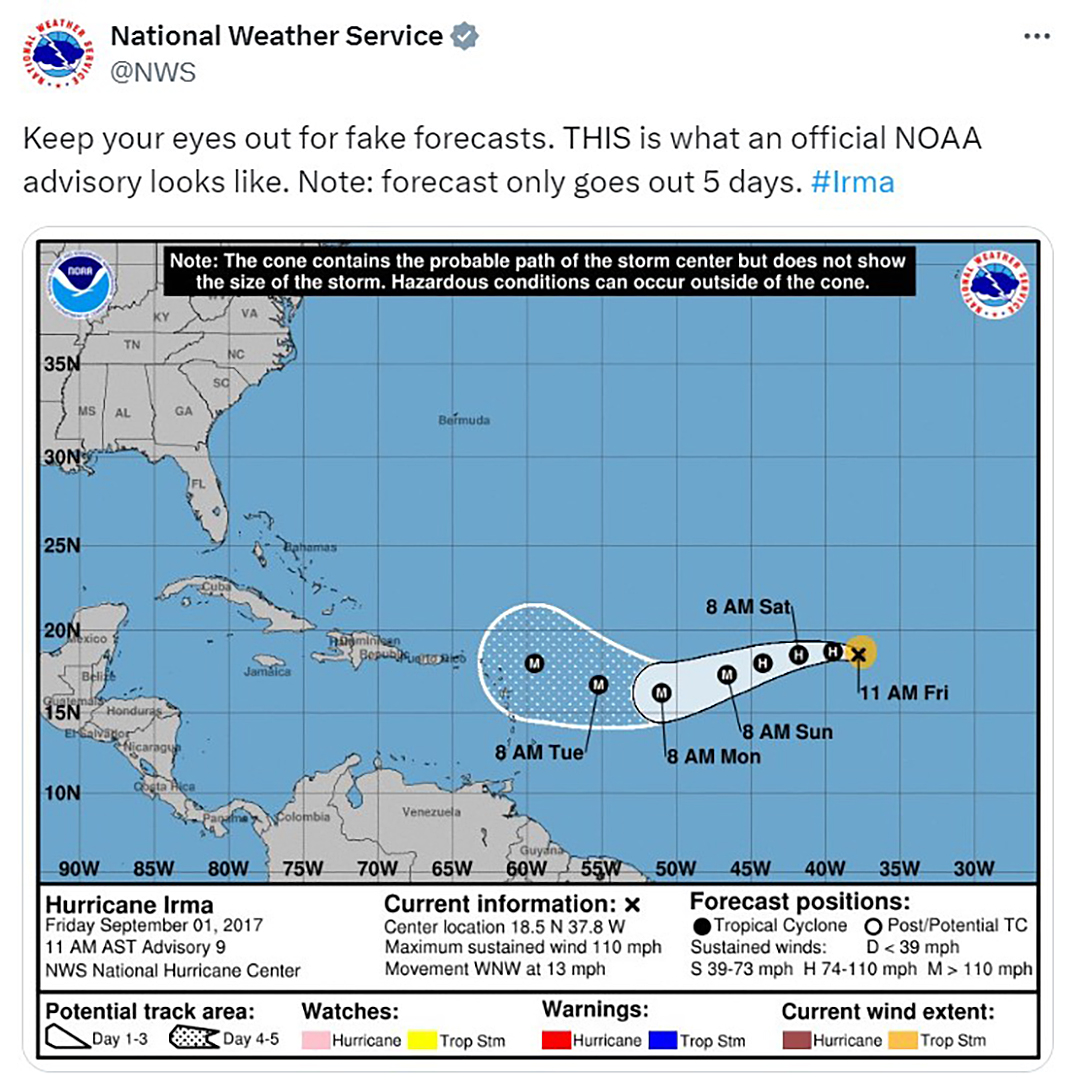

What NWS meteorologists can do, Kurz said, is post their own forecasting models — close enough to storms to be reasonably accurate and remind people they are a trusted source.

At 10:07 a.m. on Sept. 1, 2017, the National Weather Service posted an update to Twitter with a map showing the projected track of Hurricane Irma and warning followers about “fake forecasts.” Fake photos, videos and other materials purporting to be related to the hurricane circulated on Twitter and other social media platforms during and after the storm. (Source: National Weather Service / “X”)

Dane County drops ‘X’

Conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, a 2021 study found increasing misinformation and information overload on social media can generate psychological issues in people, including fatigue, panic, anxiety and depression, which can in turn be linked to violence and social unrest.

Research has linked a rise in hate speech online to the incitement or practice of such actions in-person as well, according to a 2019 study on connections between online and real-world hate crimes.

Over the past decade, hate crimes have increased nationwide, and Wisconsin hasn’t avoided these types of incidents.

The state saw a more than 50% increase in hate crimes in 2021, nearly half of which are reportedly race or ethnicity based, a 2022 FBI report found. Overt displays of hate continue, with the state witnessing incidents like a neo-Nazi march around the state Capitol in Madison in November 2023.

As digital platforms like “X” have become increasingly riddled with misinformation and hate speech, these links to mental health concerns prompted Dane County Executive Joe Parisi to take action in November 2023. He sent a message to county departments asking that they stop using “X” as a communications tool by the start of 2024.

“We do a lot of work in the mental health sphere and work with young people who may be suffering from mental health challenges in schools, and we know that platforms like ‘X’ are certainly not a healthy place for young people to be very often,” said Parisi.

“The incident in which Elon Musk liked and positively commented on a pro Nazi tweet was kind of the last straw. ‘X’ is not a place that reflects our values anymore,” he said, referencing a November incident. “So we decided it was time for county agencies to exit the platform and utilize all the other ways we have communicating with people, just like we did before Twitter, which wasn’t too long ago.”

County agencies that stopped using ‘X’ to disseminate information include the Dane County Regional Airport, Public Health Madison Dane County and Dane County Sheriff’s Office.

At 3:09 p.m. on Dec. 31, 2023, the Dane County Regional Airport posted on “X” announcing that it would stop sharing updates on the social media platform. This action followed a message from Dane County Executive Joe Parisi in November asking county agencies to cease using “X.” (Source: Dane County Regional Airport / “X”)

Grappling with misinformation online

Even as more people continue relying on social media for information, trust in news media continues to drop.

Researchers are trying to learn more about how to combat this rising misinformation.

One way to tackle the issue is to start education in schools at young ages and take advantage of community forums to emphasize the importance of sharing and understanding different identities, according to Kaiping Chen, a professor of computational communication at UW-Madison.

“To train people how to listen to each other — I think that’s even more fundamental, when we think about the future, how we should address misinformation,” Chen said. “We need to start from the education system to help people exercise their perspective to listen to each other.”

While Chen emphasizes the importance of digital literacy and educating people on how to navigate digital media, she also said government officials have a responsibility to use social media to connect with communities and individuals.

“There is an opportunity for local government to actually use not only social media, but their government platforms and other digital tools to engage with their constituents,” said Chen. “It’s just how they deliver that message.”

At 3:53 p.m. on Feb. 23, 2021, Wisconsin Emergency Management posted an update to Twitter urging its followers to consult resources from the Federal Emergency Management Agency regarding rumors about COVID-19 vaccines and other pandemic-related issues. (Source: Wisconsin Emergency Management / “X”)

The status of TikTok

When it comes to younger users, one social media platform stands out above others.

TikTok’s explosion in popularity illustrates a broader trend where younger people are turning to video-based platforms for both entertainment and news, according to Chen. And online platforms like TikTok and YouTube, which are primarily entertainment focused, are the same spaces which cause concern.

“This is where I see a huge landscape change, and this is where we see a lot of misinformation nowadays,” Chen said.

But TikTok, a business with a China-based owner ByteDance, has long been accused of stealing user information and prompted politicians to remove the app from audiences in the United States.

Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers announced a ban on the use of TikTok on state-owned devices in January 2023, joining other states that have instituted similar policies for government operations.

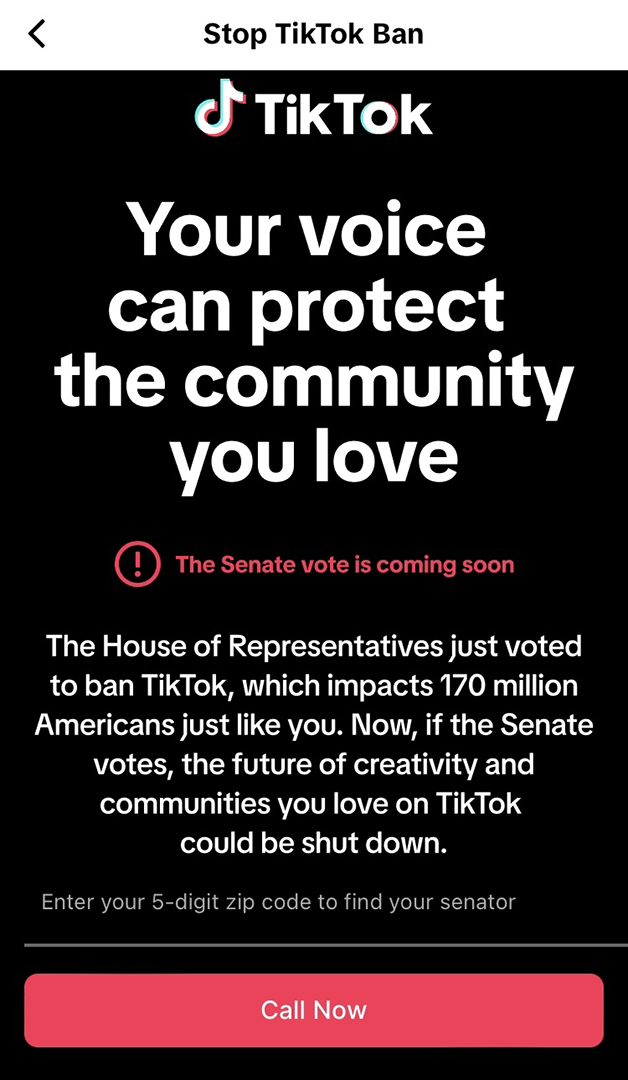

At the national level, the U.S. House passed a bill with broad bipartisan support on March 13 that would require ByteDance to either sell TikTok or otherwise ban the app from the U.S. altogether. U.S. Rep. Mike Gallagher, R-Green Bay, authored the bill, and is a prominent voice in debates over U.S. foreign relations with China. In comments to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, he said, “The bill is, at its core, a framework to tackle social media applications that are owned or controlled by a foreign adversary country.”

But banning apps completely won’t prevent people from turning to social media for information. Instead, Chen suggests that as people continue using digital platforms, these issues will likely grow.

“More people are using social media,” Chen said. “There are more platforms. There’s more flow of this information. So this is where we can see misinformation flow much faster.”

On March 7, 2024, some users of TikTok received a message from the social media platform about a vote by the U.S. House of Representatives to require its China-based owner to sell the service or face a ban. (Source: TikTok)

Reliance on social media

When government agencies like the National Weather Service notice upticks in misinformation on platforms like X and Facebook, meteorologists like Kurz and Halbach note that people seeking reliable information online need to take responsibility themselves as well.

“It’s up to people to try to figure out who’s a legitimate source and who you want to go to for this,” Halbach said.

And, as management over “X” as a company has shifted in the past couple of years, the NWS has seen impacts with engagement.

“We’ve certainly noticed that locally, fewer people overall [are using] Twitter, compared to a year or two ago. We’ve certainly seen less engagement and less reach than we used to on ‘X,'” Kurz said.

Social media is a quick and easy tool for getting out urgent weather messages, but the meteorologists noted that it is only one type of outlet for information. Other platforms remain in use and are reliable, the same way as they were before social media became another option.

“Don’t rely just on social media to get that information, but always have other sources too. You can turn to the television meteorologist or NOAA Weather Radio,” said Kurz, referencing a nationwide network of radio stations with continuous weather broadcasts. “That’s not the latest and greatest technology anymore, but still definitely serves its purpose.”

As for Dane County, government agencies did stop using “X” at the start of the year. While other units of government — from local to federal — continue to weigh their use of social media to post information, Parisi emphasized that individuals consider their own relationship with these platforms and how to use them consciously.

“We do know that platforms, and it’s not just ‘X’, are targeted for disinformation. It’s just a very negative place to be,” Parisi said. “Perhaps this will be a time in our history where we all stopped and looked back and said, ‘OK, wait a minute, what are we doing here?'”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us