Doctors debate, patients suffer: The fight over chronic Lyme disease in Wisconsin

Mainstream medicine says the tick-borne infection is a short-term ailment, but some patients insist they have Lyme-caused symptoms that last for years.

Wisconsin Watch

March 24, 2022

Maria Alice Lima Freitas is pictured at her home in Middleton on Oct. 6, 2021, with her husband John Oppenheimer. "The best way I can explain … I'm going through hell, [and] keep on going," Freitas says. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

By Zhen Wang, Wisconsin Watch

If life had gone as planned, Maria Alice Lima Freitas would be in medical school, inspired by the career of her father, a surgeon who practiced in Brazil. But instead of changing careers, the 49-year-old therapist retired from University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Freitas says her undiagnosed Lyme disease has sapped her energy, fogged her thinking and caused pain in her neck, shoulders, hands and right knee. She has three times deferred her entrance into medical school while struggling with myriad symptoms that she attributes to Lyme.

Most of her doctors say she is mistaken, and that her symptoms, which began in 2015, are due to rheumatoid arthritis.

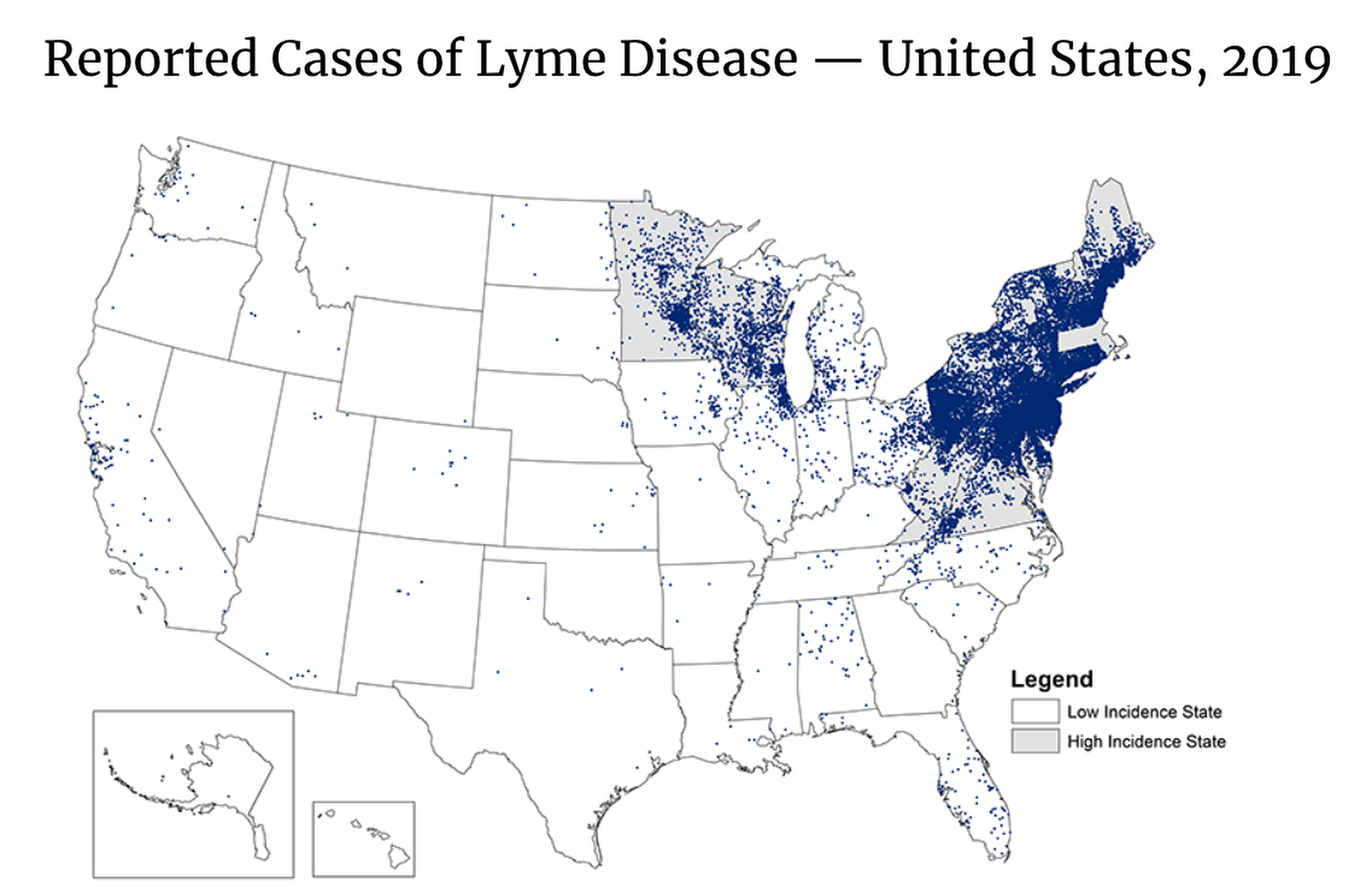

Freitas is among thousands of Wisconsinites who say they are suffering from a chronic or long-term version of the disease. The infection comes from tiny ticks primarily found in the northeastern United States, including in Wisconsin — which is a hot spot for Lyme, ranking No. 5 among states for Lyme cases in 2019.

Each dot represents one case of Lyme disease and is placed randomly in the patient’s county of residence. The presence of a dot in a state does not necessarily mean that Lyme disease was acquired in that state as the place of residence is sometimes different from the place where the patient became infected. (Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases)

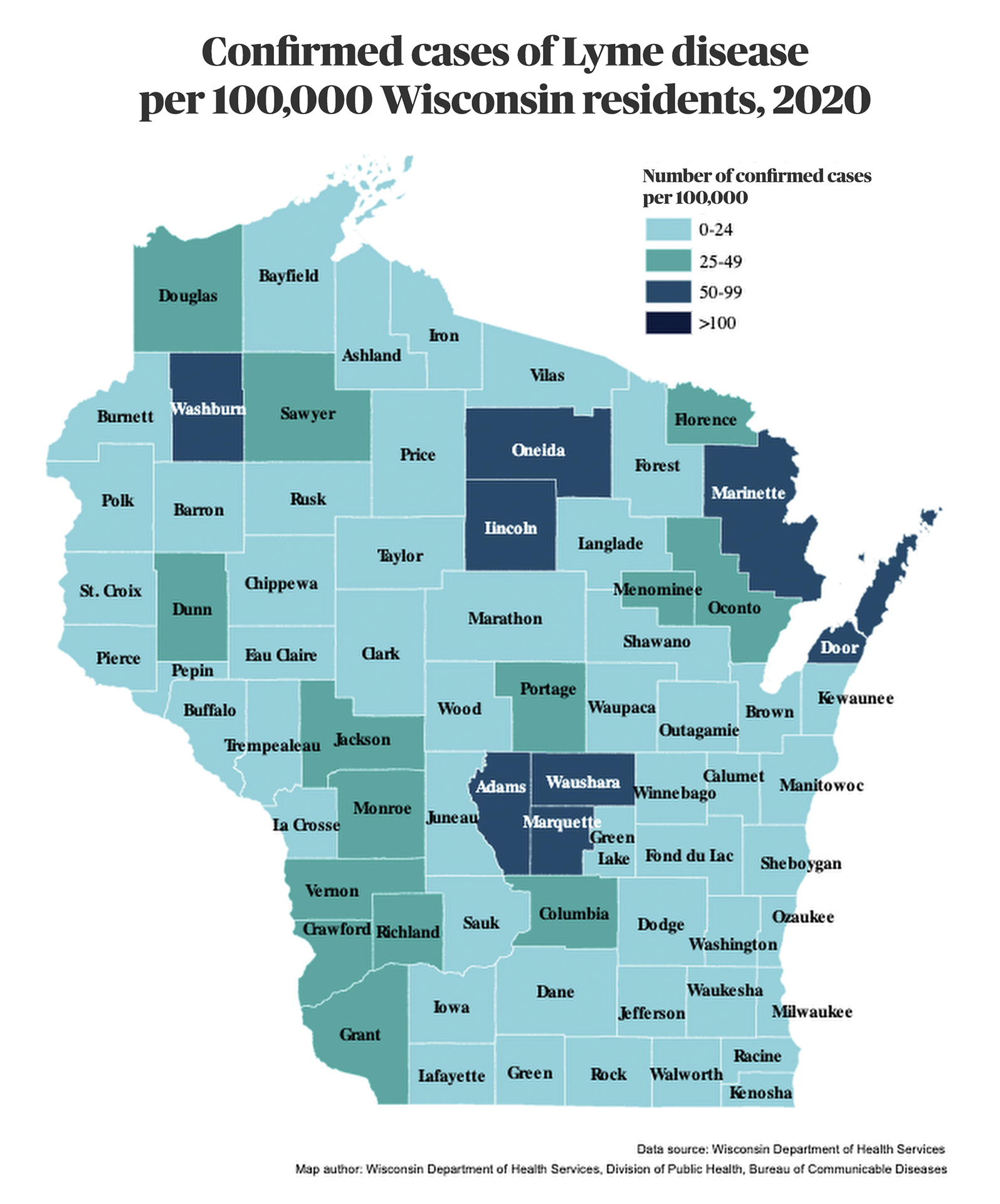

Nationally, Lyme disease infects an estimated 476,000 people a year. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services reports the state had 3,076 estimated cases of Lyme disease in 2020 — a doubling in the past 15 years. But medical entomologists say Lyme cases in the state could be 10 times higher than reported.

A map showing confirmed cases of Lyme disease per 100,000 Wisconsin residents in 2020 shows the highest rates in a handful of counties: Door, Lincoln, Marinette, Oneida and Washburn in the state’s northern half, and Adams, Marquette and Waushara in its central area. (Credit: Wisconsin Department of Health Services)

The medical establishment calls Lyme a short-term disease that usually quickly resolves with antibiotics. Self-described “Lyme-literate” practitioners argue patients like Freitas suffer from a long-haul version of the disease, often called chronic Lyme disease.

The orthodox position held by most scientific experts and some professional associations — and endorsed by U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — is that Lyme disease is an acute infectious disease. Clinical diagnosis is based on a “bull’s-eye” rash, other specific symptoms and two-tiered antibody tests. Treatment is by short courses of oral antibiotics. And persistent symptoms rarely occur.

The standard antibody testing for Lyme disease, cleared by the Food and Drug Administration and endorsed by insurance companies, has been criticized by patients and practitioners as inadequate to detect all cases of the disease. Some practitioners offer alternative tests and treatments, but insurance does not cover the cost of their care. And in extreme situations, such doctors risk disciplinary action.

For most people, Lyme disease is treatable and curable. Most patients report their symptoms cleared after a short course of antibiotics if the infection is recognized and treated early. Another 10-20% of patients develop more severe cases whose symptoms include debilitating pain, fatigue, brain fog, irritability and sleep disorders.

Dark-skinned patients face particular difficulties in getting a Lyme diagnosis. Identifying the red target symbol over light skin tone is easy for light-skinned people, but not so with dark skin tones. A 2021 UCLA study found that 34% of Black patients with Lyme disease had neurological complications compared to just 9% of whites, suggesting the disease may not have been recognized for many Black patients in earlier stages when it’s easier to treat.

Patients with persistent symptoms struggle to get a diagnosis. Wisconsin Watch has spoken with five people in addition to Freitas whose persistent, subjective symptoms fall outside of the mainstream definition of Lyme as an acute disease. Caught in the middle of the debate, they face emotional, physical, mental and financial exhaustion as they bounce between specialists in search of explanations for their pain.

“The best way I can explain… I’m going through hell, (and) keep on going,” Freitas said.

Diagnoses: Viral infection, arthritis

Freitas’ Lyme journey began in March 2019 as she battled monthly bouts of fever. She had trouble falling back to sleep late at night. Her hair rapidly fell out. And her body ached and her neck was stiff. She suffered from severe pain in her joints, bones and chest. She also felt tired. At first, Freitas attributed the exhaustion to the bladder surgery she had undergone in April. Fevers hit her in June and again in July.

The unbearable pain made it hard for her to work. It felt like someone was scraping the inside of her right knee with a knife. By August of that year, Freitas took a medical leave, unable to work.

She checked into a Madison hospital for a couple of days. She said the doctor ordered a variety of tests — but not for Lyme. Freitas was diagnosed with a viral infection, which she said failed to explain her full slate of symptoms, including electric sensations on her face and arms and forgetfulness.

Maria Alice Lima Freitas is pictured at her home in Middleton on Oct. 6, 2021. Freitas believes she has been suffering from Lyme disease since 2015. She has seen a large number of doctors, who she says have varying degrees of belief in her diagnosis. She is among thousands of patients in Wisconsin who believe they have a long-term version of the disease called chronic Lyme. Mainstream medicine considers Lyme a short-term illness that generally resolves quickly with antibiotics. ( Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Four summers earlier, Freitas said she similarly felt eye pain, knuckle pain, fatigue, forgetfulness and headaches. She recalled a rash that had stayed on her leg for at least three weeks. Freitas saw a rheumatologist at St. Mary’s in early July 2015.

The doctor noticed a red spot on her leg, but it was not the classic Lyme sign of “bull’s-eye” rash. She recalls being tested for Lyme, but the two-step testing came back negative.

The doctor deemed the red spot a likely spider bite and diagnosed her with arthritis. After taking pain medication for a month, Freitas began to feel better. When more symptoms took hold in 2019, she sensed that viral infection alone did not explain them. Freitas started reading articles about Lyme disease.

Her husband, John Oppenheimer, recalled his wife devouring medical journal articles. Freitas has a bachelor’s degree in biology from UW-Madison and a master’s in marriage and family therapy from Edgewood College. In late 2018, a Florida-based medical school had admitted her to a pre-med program, but her declining health disrupted those plans.

Freitas floated the Lyme hypothesis to a rheumatologist, who felt the joint pain and hand swelling looked more like rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Test results also suggested Freitas may have RA.

Questions about testing

Freitas was not convinced. “I have other symptoms that can’t be explained by RA,” she said. She had read journal articles about the difficulty in Lyme diagnosis, finding the recommended tests are “pretty fallible.”

CDC recommends a two-step testing process for determining whether a person has Lyme disease. Both blood tests must come out positive — or at least indeterminate — for a Lyme diagnosis to be made, the agency recommends.

The two tests measure antibodies that can remain in a person’s system for months or even years and therefore may not indicate an ongoing infection. “It cannot tell when you got infected,” said Elitza Theel, who directs Mayo Clinic’s Infectious Diseases Serology Laboratory.

And the testing has other drawbacks. “It cannot tell what disease severity (is), and it cannot tell whether or not you responded to treatment,” Theel said. “It’s important to remember that we’re not making a diagnosis based on a test result alone.”

She went on to say that the testing also cannot be used to detect other infections that may cause Lyme-like symptoms. “You would have to test for those other infections,” she said.

Maria Alice Lima Freitas is pictured at her home in Middleton, on Oct. 6, 2021, with her husband John Oppenheimer. Freitas’ life and career have been upended by a series of symptoms — including joint pain and brain fog — that she blames on chronic Lyme disease. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Freitas tested positive in the first stage of testing but not the second, showing three bands instead of the five that the CDC says are proof of Lyme disease.

She asked the rheumatologist to order a different type of test from IGeneX, a California-based commercial laboratory, hoping that the insurance company would at least cover some cost. It didn’t.

“It’s expensive. I don’t have the money. I’ve been out of my job since August,” Freitas recalled.

The results from that $2,600 test came in December 2019. It indicated she did have Lyme disease. However, the IGeneX testing is not conclusive, either, Theel said. “Their criteria are less stringent than the CDC,” she said, “which will lead to a higher number of false positive results.”

Her rheumatologist refused to accept the result, Freitas and Oppenheimer said, calling it a “shit test.”

Health woes lead to self-doubt

Oppenheimer said Freitas, once wildly independent, increasingly depends on him as she struggles with her health. The two met when she was a single mom driving a Madison Metro bus and juggling classes at the UW-Madison. Oppenheimer had overheard her speaking in Portuguese, and he tried to put together a phrase that he could speak in the same language. That led to a first date — and in 2011, marriage.

But these days, Oppenheimer said, his wife is “very drained.”

And even friends and family members question whether the symptoms Freitas describes are real.

“When everybody is saying that it is not Lyme,” Freitas said, “you start to question yourself.”

Maria Alice Lima Freitas is comforted by group leader Alicia Cashman during a meeting of the Madison Area Lyme Support Group at the East Madison Police Station in Madison on Feb. 8, 2020. Freitas believes she suffers from chronic Lyme disease but has struggled to find doctors who agree. She wept frequently throughout the meeting — the first one she had attended— as other participants shared their personal experiences. She later said she became emotional after realizing she was not imagining her symptoms. She attended the meeting with her husband John Oppenheimer, left. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

She tried a four-week course of doxycycline, the first-line antibiotics therapy for treating Lyme disease, prescribed by another rheumatologist. She began to feel better, with less pain and less brain fog. However, the symptoms returned once she completed the treatment. She even found herself starting to stutter.

Oppenheimer himself was diagnosed with Lyme disease as a 19-year-old. At the time, he was living less than 50 miles from Lyme, Connecticut, the community for which the disease was named.

He described an “arrogant unwillingness” by the medical establishment to recognize what he believes are his wife’s ongoing symptoms of Lyme disease.

“(I’m) just trying to be there with her and seemingly nothing to be able to do, and it’s horrible to watch,” he said.

Lyme controversial from the start

In autumn 1975, Polly Murray, an artist and mother of four in Lyme, reported to the state health department that she and her children were suffering from mysterious maladies, including stiff and swollen knees and rashes. And neighboring children were having similar hard-to-explain symptoms.

Physicians diagnosed the children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Another mother from the area, Judith Mensch, also contacted the state health department. Finally, the cluster aroused the attention of the Connecticut public health authorities. Yale University’s Dr. Allen Steere, who was still a rheumatologist-in-training, began searching for a cause.

The following year, Steere told the Journal of the American Medical Association that he strongly suspected the illness came from some type of infection.

In the early 1980s, Willy Burgdorfer, a medical entomologist at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, identified the bacterium that caused the mysterious affliction. It was named Borrelia burgdorferi after him.

Xia Lee, a postdoctoral vector biologist in the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Entomology, shows an adult black-legged tick, in the Susan Paskewitz Lab in Madison on Sept. 21, 2021. Lyme disease in Wisconsin has grown as the black-legged ticks that cause the disease have spread across the state. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Robert A. Aronowitz, a medical historian at the University of Pennsylvania, said the divide between mainstream medicine and Lyme patient advocates started early — with Patty Murray herself. He noted that Murray created local Lyme support groups starting in the 1980s that began to position themselves “in opposition to the leading Lyme disease physicians and scientists and their view of the disease.”

In her 1996 book, The Widening Circle, Murray warned of long-term cases of the disease. “To me, the fact that some cases seemed to be chronic, lasting for many years, meant that somehow the infection smoldered in some patients and was set off by an immune reaction, perhaps patients were being repeatedly re-infected by the organism,” she wrote.

Two camps, two approaches

Freitas saw a long string of mainstream physicians for a diagnosis — rheumatologists, an infectious-disease specialist, family medicine doctors and emergency room physicians. Then, in the spring of 2020, she began seeing out-of-network doctors in and outside of Wisconsin, and many of them didn’t take insurance.

A survey of more than 2,400 U.S. patients found that 50% of the respondents reported seeing at least seven physicians before a Lyme diagnosis, and more than half continued to suffer symptoms for at least six months after the recommended short course of antibiotics.

In January 2021, Freitas borrowed $4,000 from her mother-in-law and flew to Washington, D.C., to receive intravenous antibiotic therapy. The treatments failed to help; in fact she dropped 30 pounds in a matter of weeks. “I thought I was gonna die because I couldn’t eat,” Freitas said.

She continued to search for doctors.

On May 19, Oppenheimer and Freitas drove from their house in a quiet neighborhood in Middleton to northern Wisconsin.

They were on their way to a virtual visit with Dr. Samuel Shor. The Virginia-based internist works for the Tick-Borne Illness Center of Excellence in Woodruff, Wisconsin. Shor, who also is a clinical associate professor at George Washington University, sees patients in Wisconsin via telemedicine, charging $490 for an initial consultation.

As the former president of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society (ILADS), Shor adheres to diagnoses and treatments that the mainstream Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) generally rejects. Dr. Paul Auwaerter of Johns Hopkins Medicine, a former president of IDSA, calls physicians who treat patients for chronic Lyme “antiscience” and a danger to patients and the medical profession.

Maria Alice Lima Freitas pays about $1,200 a month for medicine, vitamins and treatment for her chronic Lyme disease. She is pictured at her home in Middleton on Oct. 6, 2021, with her husband John Oppenheimer. Freitas is now being treated by Dr. Samuel Shor of the Tick-Borne Illness Center of Excellence in Woodruff, Wisconsin. She says her brain is still sometimes foggy but emotionally she is much better and feels optimistic that a doctor is finally taking her symptoms seriously. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

“It is disappointing to me that people resort to name-calling from either side,” said Dr. Elizabeth Maloney, a family physician from Minnesota who helped write the latest guidelines on Lyme disease treatment. “It’s not helpful, and it does undermine patients’ confidence in our profession as a whole.”

The guidelines issued by IDSA maintain the group’s recommendations against antibiotic treatment for patients with persistent symptoms. It has also removed a previously endorsed term — Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS) — for defining patients with persistent symptoms after short courses of antibiotic therapies.

“They don’t even want to go into that quagmire anymore,” said Maloney, who leads the Partnership for Tick-Borne Diseases Education. “They do not really talk about what to do with patients who do not fully recover. It’s kind of a black box.”

The disease is complex. If untreated, Lyme can have wide-ranging effects on skin, joints, nervous system or the heart. The infectious agents attack connective tissue and can move around and “find their own way to … various parts of the body,” said Dean Nardelli, an associate professor who studies later-stage Lyme disease at the UW-Milwaukee’s Biomedical Sciences Lab Programs.

In a 2019 article in the journal Antibiotics, Shor said chronic Lyme is “often dismissed as a fictitious entity.” He and his co-authors consulted more than 250 peer-reviewed articles pointing to “a multisystem illness with a wide range of symptoms,” either continuously or intermittently, lasting at least six months.

“Signs and symptoms may wax, wane and migrate,” they wrote.

Other pathogens to blame?

Shor and his co-authors, including Maloney, propose that the lingering symptoms are caused by several pathogens from the Borrelia burgdorferi family or other tick-borne pathogens.

Nardelli said there’s a variety of symptoms and severity in Lyme disease patients, and those symptoms can be caused by the inflammatory responses against the microbes.

“Inflammation is a huge part of the immune response. It’s one of the frontline defenses we have, and it has this negative connotation, but it is intended for good,” he said. “Your immune response (is) trying to kill the bug … and in doing so, can cause damage, essentially.”

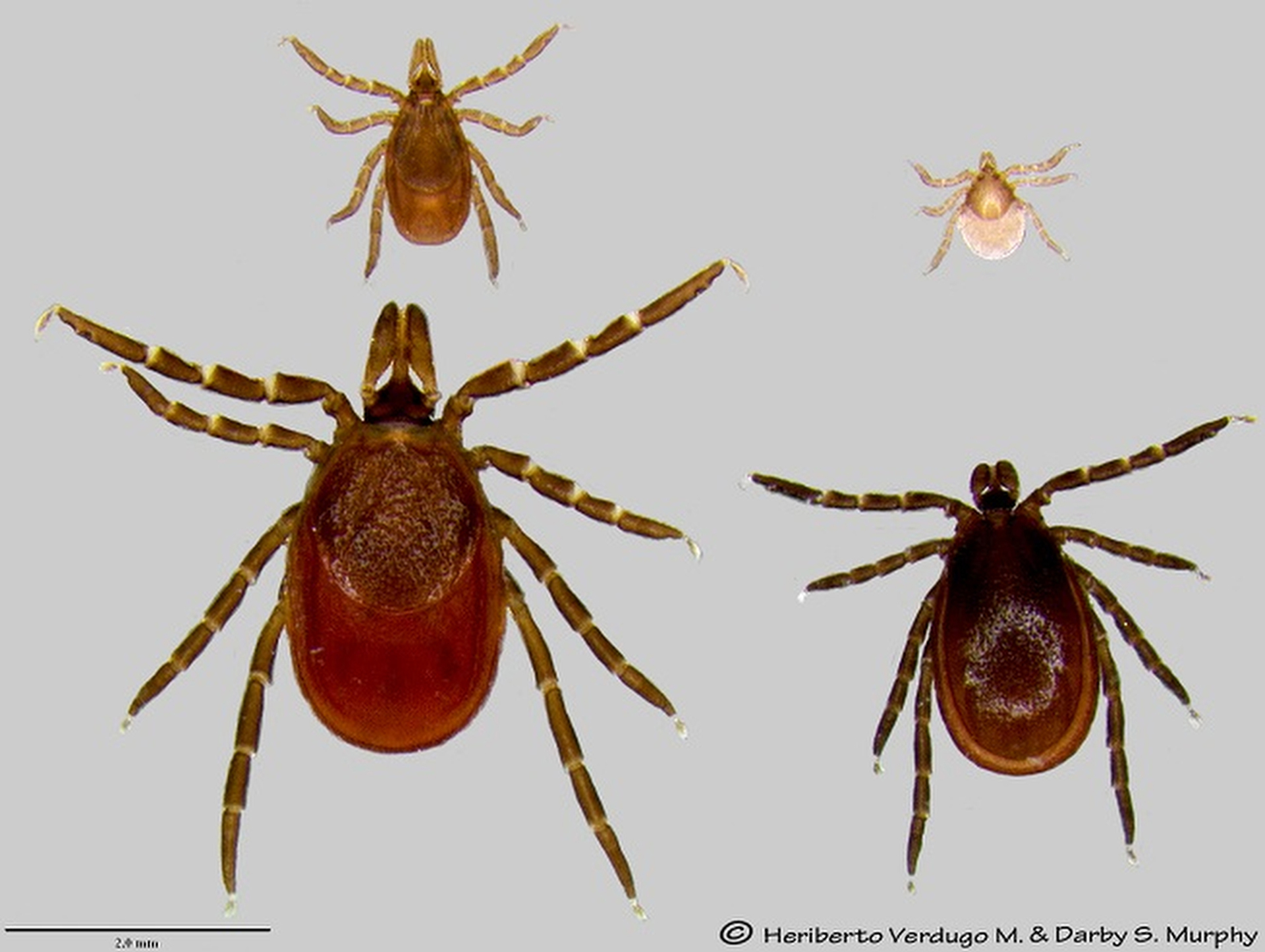

The black-legged tick, or deer tick, is the vector of the bacteria that cause Lyme disease. Deer ticks are present everywhere in Wisconsin where there is forested habitat. Pictured clockwise from top left: nymph, larva, adult male, adult female. Deer ticks have three life stages, the larva becomes a nymph, which then becomes an adult. (Credit: Courtesy of UW-Madison Department of Entomology)

Some theories suggest that variants of the Lyme bacteria are resistant to antibiotics. Others argue that chronic Lyme is caused by a powerful immune reaction — or it may even trigger an autoimmune disease. The central neural networks may be altered, having a significant impact on symptoms — or a combination of these factors.

Nardelli is investigating how the immune system is affected by the Lyme bacterium, research that could contribute to treatments for people with prolonged reactions after the infection. He said science can be a slow process of acquiring new knowledge, and it’s “tough” for patients who are suffering with no clear answers.

That can lead them to seek out untrustworthy practitioners or fall for costly treatments that don’t work. “You go out and find doctors that diagnose everything as Lyme disease,” Nardelli said.

For complicated cases, Maloney said physicians should approach patients as a detective would, whittling away other possibilities until getting to a diagnosis.

“The whole goal is to get people the right diagnosis so they can get the therapy that they need,” she said.

Freitas said she trusts Shor, who has embraced her IGeneX test results for Lyme and has also diagnosed her as having several afflictions: babesiosis, which has some of the same symptoms as Lyme and can come from the same ticks; bartonella, also known as cat scratch fever; and chronic fatigue syndrome.

Alternate treatments offer relief

Freitas now takes Epsom salt baths on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays and uses an infrared sauna for “detoxification,” saying it makes her body feel better.

And she now takes 30 pills each day, interspersing antibiotics with herbs and dietary supplements, which cost upwards of $1,200 a month.

“For babesia … I’m taking liquid gold … Mepron,” said Freitas. “It’s really expensive. It’s 50 bucks for 80 milliliters, which lasts two weeks.”

She gave up dairy, gluten, and sugar to reduce inflammation.

And she meets with Shor monthly online from her house at a charge of $250 per visit, which insurance does not cover.

“It was to me (that) the money is well paid. I’m having peace of mind,” Freitas said. “I feel like I’m getting better.”

Freitas said she started gaining back some weight in June. Her mind has become a bit clearer. Her long-term memory seems back a bit, too. “I’m getting out of the graveyard,” she said.

Maria Alice Lima Freitas says since starting treatment for chronic Lyme disease, she has begun to regain weight and her mind has become a bit clearer. “I’m getting out of the graveyard,” she says. She is seen at her home in Middleton on Oct. 6, 2021. (Credit: Coburn Dukehart / Wisconsin Watch)

Said Oppenheimer to his wife: “What I’m seeing is you’re better relative to the beginning of (2021), because you’re still not good.”

For Freitas, the struggle for recognition — and relief from her symptoms — continues. She and her husband remodeled their home over the summer, refurbishing their two-story house with a plan to rent out one level to pay for Freitas’ ongoing treatments.

And she still holds out “a little flame of hope” of one day becoming a doctor — just like her dad.

Former WPR/Wisconsin Watch reporter Bram Sable-Smith contributed to this story. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us