Beset by the pandemic, personal threats and politics, local clerks focus on elections

Here & Now extra: As political furor over the 2020 vote continues, elections officials around Wisconsin are experiencing burnout, prompting an ad campaign to promote their service to their communities – the clerks for Rock County and the city of Janesville share their experiences amid these stresses.

By Gaby Vinick | Here & Now

April 5, 2022

Voters in Fitchburg wait in line to cast their ballots in the election on Nov. 3, 2020. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

A year and a half has passed since the 2020 presidential election, and a growing number of local elections officials around Wisconsin are feeling beleaguered and burned out as they juggle shifting voting rules amid suspicion and threats.

“A lot of clerks feel like they’re under a microscope right now,” said Lisa Tollefson, the Rock County Clerk. “There’s a concern that they’re gonna make a mistake — something minor, and it’s going to get blown up. That’s a lot of pressure, especially on somebody who’s very new, having to deal with that kind of scrutiny put on everything that you’re doing.”

As a county clerk, Tollefson is quite familiar with elections. She has sought the support of a majority of Rock County voters as a candidate in two elections – winning in 2016 and 2020. In that office, she has administered dozens of elections, one of the job’s key responsibilities. She has also previously served as a municipal clerk.

Tollefson is familiar with the accusations and hostility directed toward local election officials. Hours after polls closed on the night of the Nov. 3, 2020 election, an error in a media feed distributed by the Associated Press briefly transposed its Rock County vote counts for presidential candidates Joe Biden and Donald Trump. Nearly a week later, supporters of Trump started making unfounded accusations that the actual votes had been changed.

Tollefson noted that the county election website’s vote totals did not flip, and its final count was confirmed in the official canvass. A series of angry phone calls to the clerk’s office followed. Worried about the safety of staff and her family, Tollefson sought and received assistance from the Rock County Sheriff’s Office.

The office of county clerk is partisan. Tollefson runs for office as a Democrat, but has also been endorsed by the Republican Party of Rock County, whose chair defended her work and transparency in the wake of the November 2020 furor. However, the vast majority of elections clerks in Wisconsin are nonpartisan and at the municipal level, administering the voting process in towns, villages and cities. In Rock County, there are over two dozen municipal clerks.

As the clerk-treasurer for the city of Janesville, Lori Stottler said election clerks have baseline expectations when it comes to navigating these job pressures.

“If you consider somebody sending me an email saying ‘we are watching you’ is a threat, well then so be it,” she said. “It’s a public service position, and I’ve got a job to do, and I’m going to do it.”

Tollefson concurred about expecting some measure of antagonism.

“You expect to get some of that. It kind of comes with the job — some of it goes to that line, but doesn’t quite cross it that makes you feel uncomfortable,” Tollefson said. “You’d think that some of this would calm down, and some of it has.”

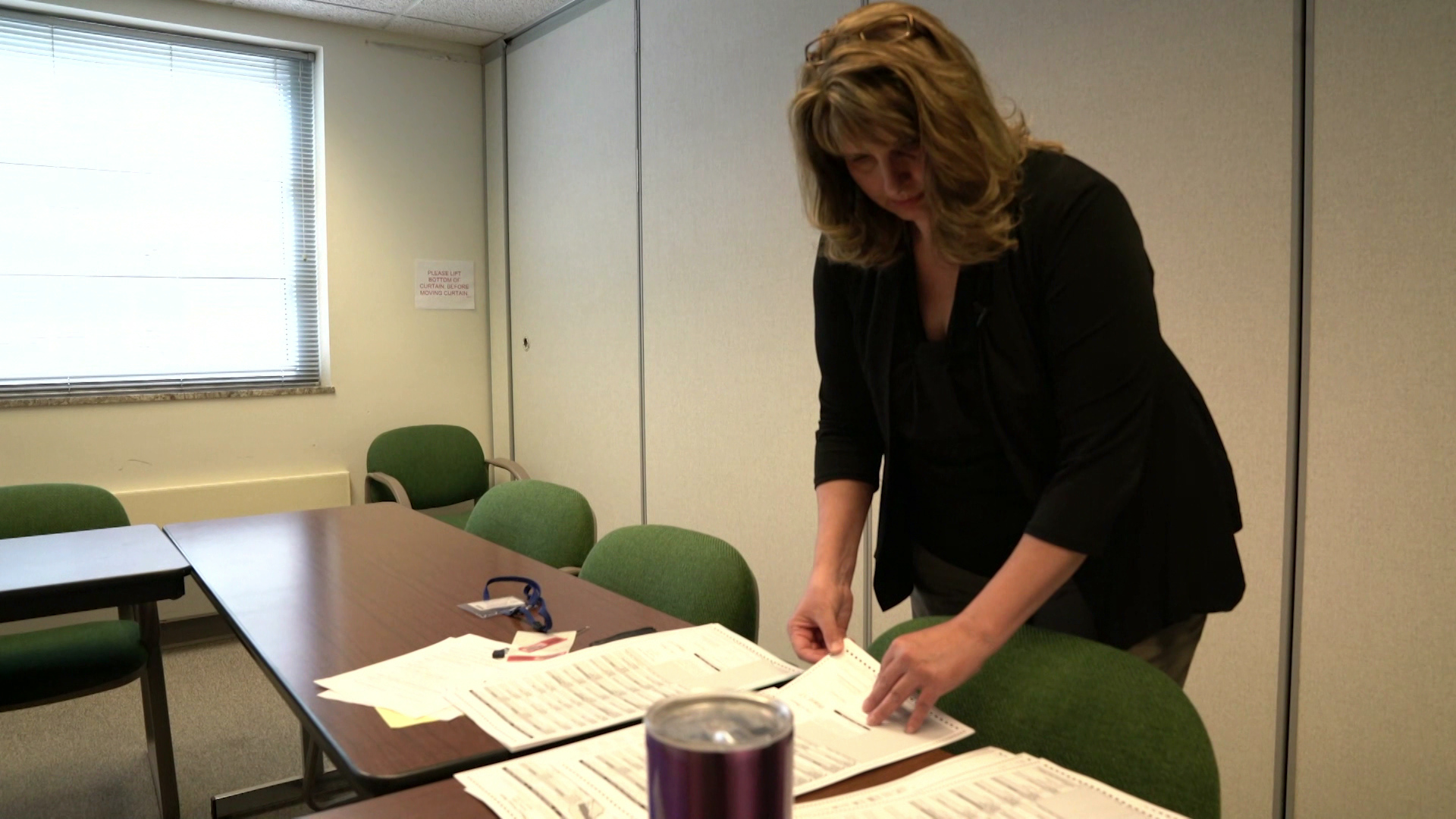

Rock County Clerk Lisa Tollefson explains how the election process works at her offices in Janesville in October 2021. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

Nevertheless, concerns are growing among local election officials across the United States.

In March 2022, the Brennan Center for Justice released its findings in a poll of 596 local election officials around the nation, conducted between Jan. 31 and Feb. 14. The survey found that one in six local election officials have personally experienced threats — over the phone, in person, through social media and by mail. Meanwhile, over three-quarters felt that threats have increased in recent years.

The U.S. Department of Justice announced in July 2021 it would launch a task force to investigate threats. The following month, a Reuters investigation found that after the 2020 vote, more than 40 election workers and officials in eight battleground states received more than 100 threats of death or violence, but many never heard back from local law enforcement after reporting threats.

Confidence in elections

“Trying to run the election during the pandemic was much more stressful than now,” said Scott McDonell, who has served as Dane County Clerk since the beginning of 2013. “It’s now more a frustration of the constant lies and misrepresentations about the election.”

Former President Donald Trump has continued to make baseless claims that the 2020 presidential election was “rigged.” In Wisconsin, President Joe Biden won the state by over 20,000 votes, a margin confirmed in a recount sought by Trump that cost his campaign some $3 million. Yet rejection of the election results continues, including from lawmakers in the state.

Despite logistical challenges amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 election has been found to be reliably conducted. About a week after the vote, a pair of federal election security committees issued a statement declaring it to be “the most secure election in American history.” Research conducted in Wisconsin has found high levels of confidence among voters. A report released in September 2021 by the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that four out of five voters surveyed expressed similar levels of confidence in the 2020 election as they did in 2016.

However, as more local election clerks feel unappreciated and under attack, a group of nonpartisan local government organizations in Wisconsin are seeking to encourage support for their work. The League of Wisconsin Municipalities, Wisconsin Counties Association and Wisconsin Towns Association released an advertisement featuring a trio of municipal clerks from the village of Cobb, village of Kohler and city of Neenah.

“We trust our local elections because our friends, families and neighbors run them,” said one of the clerks.

Tollefson offered a similar message about the people who make sure voting systems operate at the local level.

“When you go into your polling location, those are people from your community,” she said, noting that many take time off to lend a hand with elections. “They’re the ones helping protect your elections with all the checks and balances.”

“Clerks work really hard behind the scenes to do their jobs,” Tollefson added. “Most people do not understand the amount of work that they do to meet their community, to keep everything running correctly.”

McDonell concurred.

“We don’t assume anything in an election — I assume that there’s a failure at every single point,” he said. “And we have a system to check for failures all along the way.”

Retaining experienced election clerks

Hostility toward local election workers is one factor hampering the ability of local governments to retain and find clerks. Lisa Tollefson fears this environment will encourage more to find a different occupation or retire. Should more clerks leave, she explained, there’s a greater risk of losing institutional knowledge about how elections work.

“You may have people who aren’t just familiar with all the different laws and the different statutes that they need to follow. And that’s where I’m concerned,” Tollefson said.

Jerry Deschane, executive director of the League of Wisconsin Municipalities, discussed the goals of its ad campaign in an April 1, 2022 interview on Here & Now. He noted Wisconsin has 1,832 municipalities that require a clerk who is trained and certified.

“What is happening is the great retirement. Clerks are walking. I can’t quantify it for you with statistics, but anecdotally we’re getting more than a few clerks saying, ‘I just don’t need these headaches,'” said Deschane.

The divisive political environment and ongoing effects of the pandemic also hurt efforts to retain election officials. Lori Stottler described the situation in Janesville as a “perfect storm.”

Stottler served as the Rock County Clerk before Tollefson, and subsequently worked as clerk-treasurer for the city of Beloit before getting hired by Janesville in August 2021. She, too, continues to try to assuage skepticism and refute accusations about how elections are conducted at the local level.

The personnel situation may not be as dire as feared, though. The Elections Research Center report found that the turnover rate for local clerks in the first eight months following the 2020 presidential election was 12%, a small rise from the 9% rate observed in 2016. That said, while 62% of local clerks in Wisconsin agreed the 2020 election did not affect their desire to continue working in this role, about 30% reported “feeling tired and run down.”

In the pandemic’s wake

“I think one of the best things that our elected officials can do is try to reestablish the norms of trust that we used to have when it comes to how the state administers elections and how the state engages in other kinds of governing behaviors,” said Michael Wagner, a professor in the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication, and a faculty affiliate of the Elections Research Center.

Before 2020, the Brennan Center’s poll found just 13% of local election officials reported feeling “very worried” about politicians interfering with and applying pressure on voting results. Two years later, that number had doubled to 36%. As the Election Research Center’s report found, the burnout clerks are experiencing largely stems from frustration over changing statewide rules about how elections are conducted. That leaves a backlog of work piling up, as clerks must “alter their workflows, retrain poll workers, and update the public about new developments.”

Wagner suggests elections officials focus more on explaining the intentions behind different changes made to keep people safe during the pandemic, and clearly describe how ballots are counted and canvassed among individual municipalities.

At the same time, local clerks are keeping a close eye on potential changes to election laws in the state, especially given the important training process to certify poll workers.

“I don’t think anything is going to be quite as crazy as the pandemic was, when they had to reinvent an election on about four weeks’ notice,” said Scott McDonell. “But nonetheless, last minute changes are probably the worst thing you want to do.”

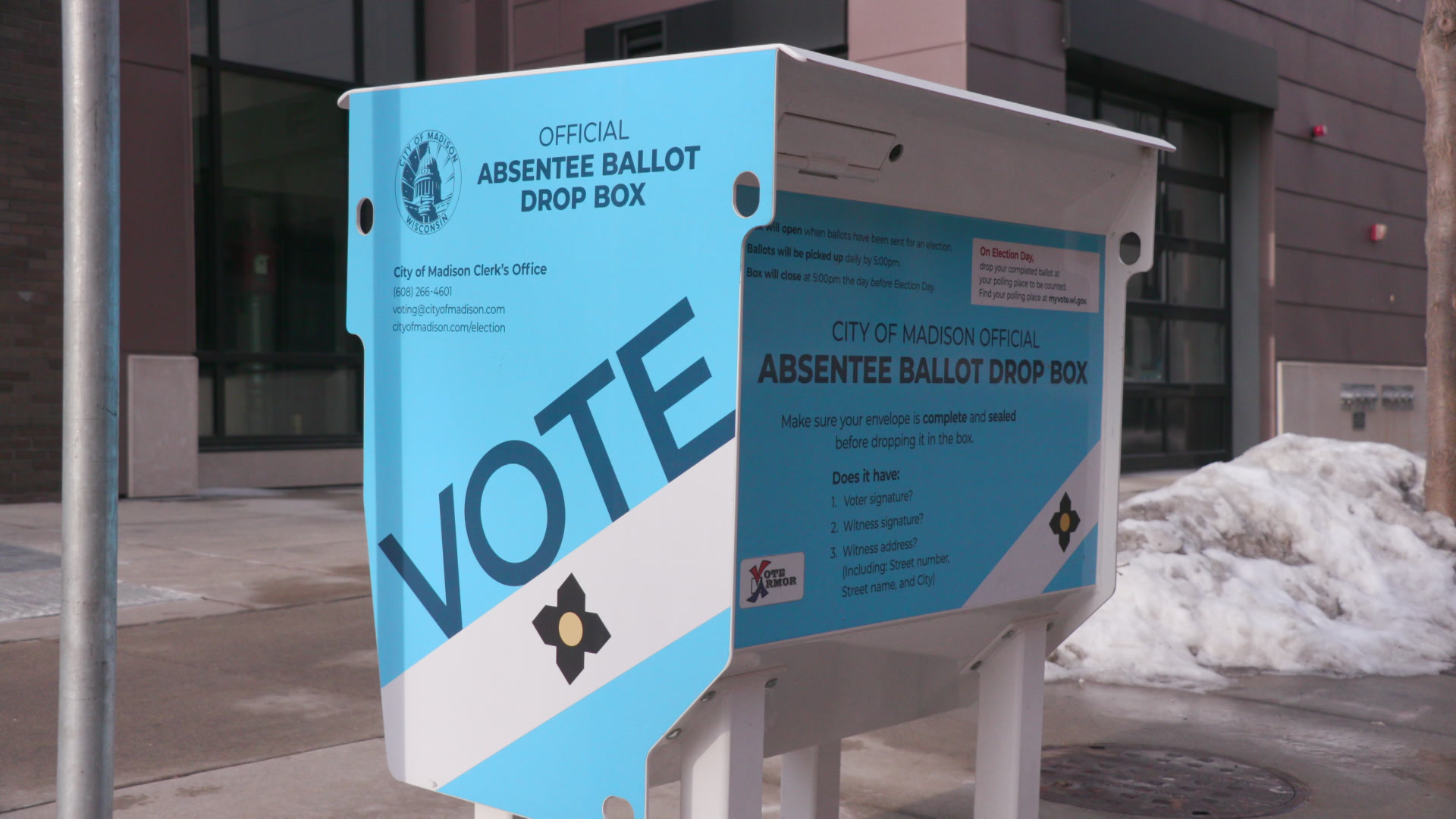

An absentee ballot drop box stands in front of a fire station in downtown Madison on Feb. 1, 2022, two weeks before the spring primary election on Feb. 15. On Feb. 11, the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled in a lawsuit that state law did not permit absentee ballot drop boxes. This ruling was stayed for the primary only days later, but drop boxes were banned from in the spring election on April 5 as the Court continued to consider the issue. (Credit: PBS Wisconsin)

He cautioned against shifts to how, when and where voters can cast their ballots right before an election.

“We ask a lot of policymakers, go ahead and debate the issues — we think that’s fundamentally healthy, but try to time that so you’re not doing it right up against an election because frankly, it can be chaotic,” McDonell added. “And when the public is confused, there’s a last-minute change that in itself will breed distrust, which should be the opposite of what we’re trying to do.”

In Janesville, Lori Stottler is interested in more resources and attention toward voter outreach. “My staff is strained,” she said.

Amid uncertainties about election regulations and alongside worries about threats to election officials and workers, McDonnell is troubled by “the idea that the losing side won’t accept the results.”

Wagner drew connections between these concerns.

“The brilliance of democracy is that it’s for the loser. If you lose an election, there’s another one,” he said. “And to continue pointlessly combatting an election where the result is already painfully obvious to the point that people’s lives or safety are being threatened in some cases is beyond ridiculous.”

Yet there are those who remain unwilling to listen to explanations about how the election process works.

“There’s a lot of people that won’t change their minds,” Stottler said. “They just believe what they believe, and I have to be good with that, too.”

Editor’s note: Kristian Knutsen contributed to this story.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us