A Year Into The Pandemic, What's Driving Varied Coronavirus Rates Across Wisconsin?

What factors might be driving the comparatively lower case and death rates in Dane and St. Croix counties, located hundreds of miles from each other? What stories do these factors tell about COVID-19's impacts?

By Will Cushman

February 4, 2021

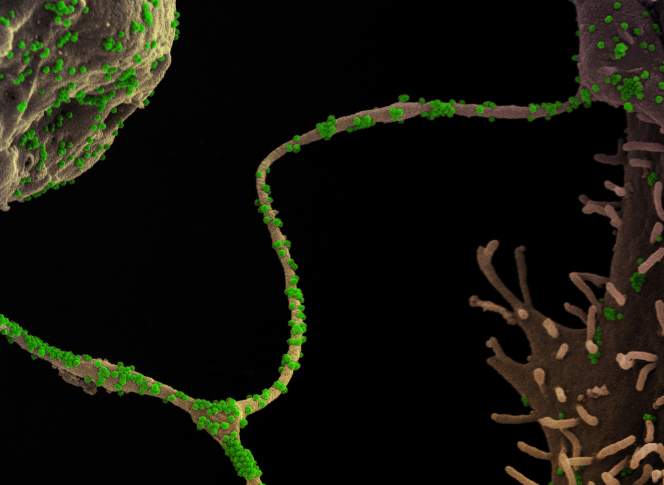

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of CCL-81 Cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus particles crop

Situated along the eastern banks of the St. Croix River just 18 miles from downtown St. Paul, the community of Hudson, Wisconsin, serves as a primary gateway to the Badger State for Minnesotans from the Twin Cities metro area. As such, in 2020 Hudson emerged as a magnet for would-be revelers seeking to avoid Minnesota’s restrictions on bars and restaurants in response to the COVID-19 pandemic — rules that fell away as soon as they would cross the Interstate 94 bridge into Wisconsin.

The stream of diners and barhoppers left local public health officials worried that Hudson, the largest city in and seat of St. Croix County, would see a subsequent surge in COVID-19 cases. A year into the pandemic, St. Croix County’s COVID-19 per capita case and death rates — the number of cases and deaths confirmed for every 100,000 residents — are among the lowest in Wisconsin and compare favorably to other parts of the Twin Cities region.

A year after the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in a patient in Wisconsin, more than 545,000 people in the state have tested positive for the coronavirus and more than 5,900 have died from the infection.

Put another way, about 1 out of every 10 Wisconsinites have received a COVID-19 diagnosis since February 2020, and among those ranks, about 1 in every 100 has died.

COVID-19’s impact on Wisconsin’s diverse communities has not been uniform. In line with patterns seen elsewhere around the United States, the hardest hit nation in the world, the risk of developing serious symptoms that require hospitalization or lead to death varies by age, race and ethnicity. As the pandemic enters its second year, these differences and other factors are driving a widening divergence in the impact of the disease on different parts of the state.

Health officials announced Wisconsin’s first confirmed case of COVID-19 on Feb. 5, 2020. A Dane County resident received the diagnosis soon after arriving from a trip to China, where the coronavirus pandemic originated. More than a month passed before another case was confirmed in Pierce County, located immediately south of St. Croix County, and followed soon after by a rapid rise in new cases and sweeping restrictions on public life meant to slow COVID-19’s spread.

In Dane County — home to the state capital of Madison and Wisconsin’s second largest by population with 546,695 residents in 2019 — health officials have tallied more than 38,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases since February 2020. The county’s case total is behind only Milwaukee and Waukesha counties, the state’s first and third largest by population.

When adjusted for population, Dane County’s rate of confirmed cases compares more favorably to most other Wisconsin counties, however. As of mid-January 2021, the county home to nearly one-tenth of the state’s residents recorded a cumulative rate of about 6,980.9 confirmed cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 residents, one of the lowest rates among Wisconsin counties on a per capita basis.

Dane County’s COVID-19 rates did not always compare so favorably to elsewhere around the state. From the pandemic’s outset until early fall 2020, Dane County’s rate consistently ranked among the highest in Wisconsin. But through the fall, the state’s case numbers ballooned as the coronavirus spread through stretches of Wisconsin that had previously escaped the pandemic’s worst. By the start of 2021, the county’s rate was the third-lowest in Wisconsin, and it’s since hovered around that position.

One of the only counties with a lower rate of confirmed cases is St. Croix County. While the county has reported more confirmed total cases than two-thirds of Wisconsin counties — as of Feb. 3 — on a per capita basis it ranks second lowest in the state.

Both St. Croix and Dane counties also rank at the low end in Wisconsin for confirmed COVID-19 deaths when adjusted for population, with the fifth and sixth lowest per capita rates, respectively, at the beginning of February 2021.

For comparison, Wisconsin’s overall COVID-19 case rate is nearly one-third higher than the two counties’, and the median rate among counties — 8,931 per 100,000 — is about 25% higher. The state’s COVID-19 death rate is 120% higher.

Dane County anchors a cluster of counties in southern Wisconsin with generally lower COVID-19 rates, including Richland, Green, Iowa and Sauk. Meanwhile, two rural counties with case rates near or lower those in Dane and St. Croix — Bayfield and Vernon— have recorded much higher death rates, exceeding even the state’s overall death rate.

What factors might be driving the comparatively lower case and death rates in Dane and St. Croix counties, located hundreds of miles from each other? What stories do these factors tell about COVID-19’s impacts?

As with many aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic, contributing factors aren’t cut and dried. Public health experts in Wisconsin are cautious about pinning a given community’s experience with COVID-19 on any particular factor.

Testing

Any potential explanations for a given place’s COVID-19 rates — whether good or bad — depends on whether those statistics accurately reflect reality. After all, a low number of official COVID-19 cases could obscure the true toll of the coronavirus in communities with poor access to or embrace of testing.

The possibility of such a scenario is one reason that epidemiologists like Patrick Remington, a professor emeritus of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, urge caution when comparing local COVID-19 rates. The amount of testing is just one source of potential inaccuracies in official figures, he said.

“There are hundreds of sources of bias that would potentially lead to differences in the number of cases and the number of deaths” in a community, Remington said. That’s why it’s important to contextualize local COVID-19 statistics as much as possible, he explained.

For instance, looking at case rates in conjunction with the percentage of tests that come back positive — the test-positivity rate — can help shed light on whether case rates reflect a reasonable estimate of the share of a community that has been infected. A low test-positivity rate, for instance below 5%, suggests that testing is catching most infections in a community, whereas higher rates indicate a higher number of infections aren’t being detected and therefore aren’t reflected in official public health reporting.

According to COVID-19 data released by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, after experiencing a lull in early summer, most counties saw test-positivity rates climb through the fall of 2020 to levels suggesting a significant number of infections were likely going undetected. While this pattern holds true in Dane and St. Croix counties, both have experienced lower peaks and shorter periods of consistently high positivity rates than most other counties in Wisconsin.

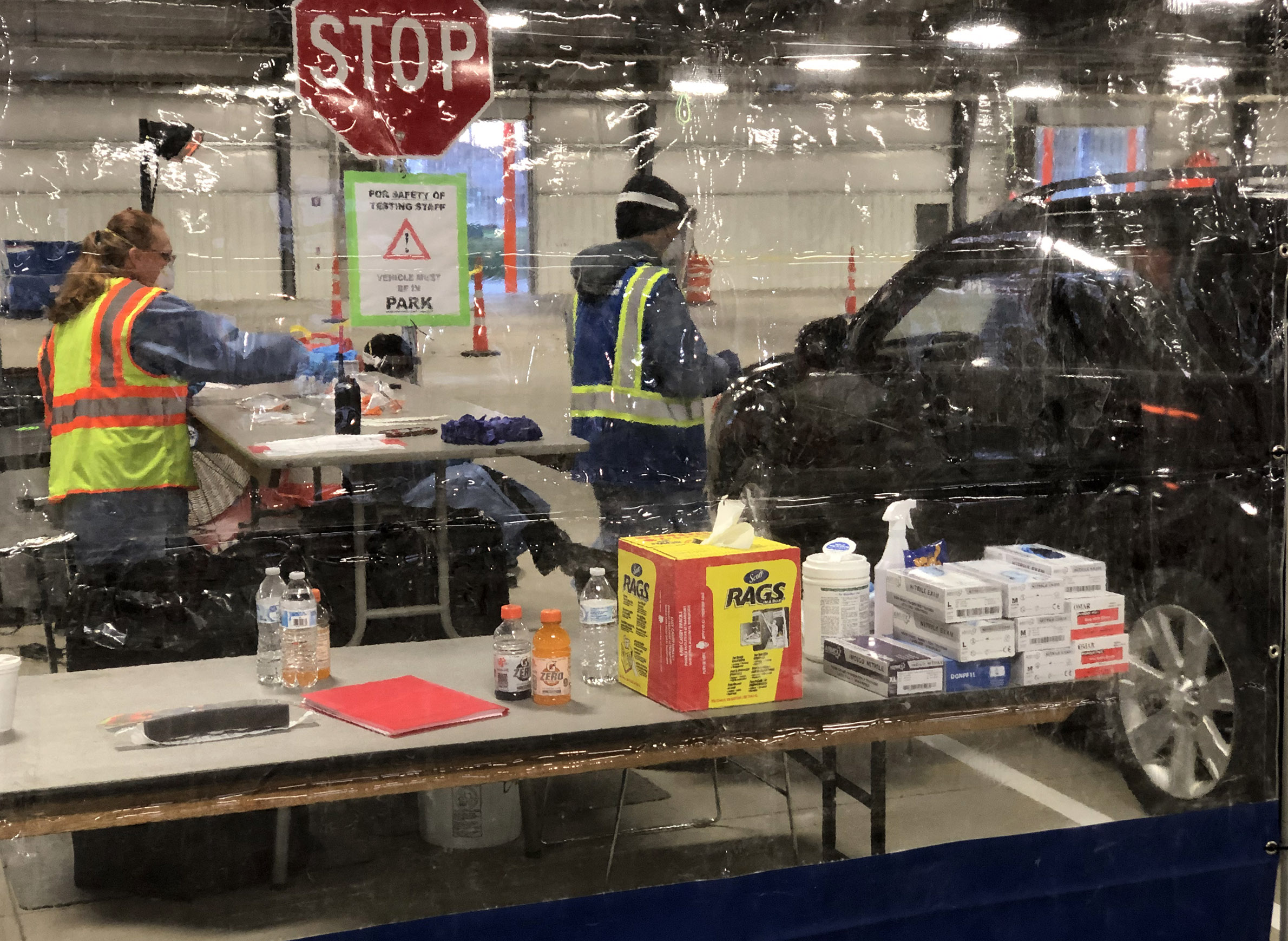

Public health officials in Dane County pointed to relatively easy access to testing as one of many potential reasons that it COVID-19 case rates have remained lower than in most other parts of the state. Since the spring of 2020, the Alliant Energy Center in Madison has been repurposed from a convention space to a public testing site that can collect thousands of specimens every week. That’s in addition to more than a dozen other public testing sites located throughout the county, including on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, as well as through healthcare providers.

“We’ve had robust testing since the beginning,” said Janel Heinrich, director of Public Health Madison & Dane County. “Robust testing allows us to identify folks who are symptomatic and asymptomatic and who have a positive diagnosis early on, get in touch with their [contacts], and then we can provide isolation and quarantine support.”

While the widespread local availability of testing supports Dane County’s COVID-19 mitigation efforts, it also suggests that the county’s relatively low official case rates are likely not too far removed from reality.

Assessing the ease of testing for residents of St. Croix County is not as simple. One major factor is many residents in the border county travel to Minnesota for work, shopping and healthcare. Still, test-positivity rates in St. Croix County have consistently been among the lowest in Wisconsin throughout the pandemic, which could translate to a lower number of undetected infections there as well.

In short, evidence gleaned from testing suggests that the comparatively lower COVID-19 case rates in Dane and St. Croix counties are not simply a data mirage and do arguably reflect the reality of the pandemic.

Outbreak

Even when considering that COVID-19 case and death reporting is imperfect, potential data lapses are unlikely to explain the lighter case loads in Dane and St. Croix counties compared to most other Wisconsin counties.

Epidemiologists and public health officials in each acknowledge they have in part benefited from local circumstances — both in terms of broad characteristics and the unique experiences they’ve encountered over the first year of the pandemic.

Janel Heinrich, Dane County’s public health director, pointed to the state’s first case as a counterintuitively fortuitous event for the local response.

“[That] supported our ability to organize very quickly and [make] early connections with the CDC,” Heinrich said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lent valuable technical assistance that Heinrich credited with helping Dane County build infrastructure to respond to the virus — one centered on testing, contact tracing and isolation and quarantine support.

In St. Croix County, public health officials also credited early experience with COVID-19 as beneficial to building an effective local response to the disease. In their case, this early experience was informed by the spring surge in cases in the Twin Cities metro area.

“If you were following Minnesota at all early on [in the pandemic], they were exceeding our case rates from the state of Wisconsin pretty quickly,” said Kelli Engen, health officer for St. Croix County.

With the Twin Cities region seeing hundreds of new cases per day in the late spring and early summer of 2020, Engen said St. Croix County’s close ties meant it too experienced an early rise in cases as the outbreak expanded across the border.

“We watched as [Minnesota’s] nursing homes and other facilities really did become impacted by COVID,” Engen said.

Witnessing the disease’s early toll on vulnerable populations just across the St. Croix River spurred the St. Croix County Health Department to prioritize mitigation efforts aimed at local nursing homes, including assigning one of its handful of public health nurses to provide daily technical assistance to these living facilities and serve as a direct link to assistance.

While those resources have not shut the coronavirus out of long-term care facilities in the county — which by the end of January 2021 counted 47 public health investigations at long-term care facilities over the course of the pandemic — Engen credited her staff’s work with keeping the local toll from becoming even worse.

Demographics

Long-term care facilities, including skilled nursing homes and assisted living communities, are home to many of Wisconsin’s residents who are most at-risk to COVID-19. Age is a primary risk factor for serious outcomes up to and including death, and the fact that the coronavirus — readily transmissible via respiratory droplets indoors — can spread quickly where people congregate or live in group settings.

Indeed, even as a lower percentage of Dane County residents have received COVID-19 diagnoses than in most parts of Wisconsin, nursing homes and assisted living communities have proven to be difficult settings for efforts to control the virus.

“We have seen, unfortunately, high numbers [of cases] in long-term care facility settings,” said Kat Grande, a public health supervisor who leads a team charged with analyzing local COVID-19 data for Public Health Madison & Dane County.

Characteristics of Dane County’s overall population may be a factor keeping COVID-19’s impact — particularly in terms of deaths — less severe outside of group living settings than in some other parts of Wisconsin.

For starters, Dane County is home to fewer residents 65 and older as a proportion of its population than most counties in the state, as well as Wisconsin as a whole. The same is true for St. Croix County. Nearly 90% of the deaths attributed to COVID-19 have occurred in this older age group.

However, another county with a similarly small population of residents 65 and older — Menominee County — has experienced one of the highest COVID-19 death rates in Wisconsin, along with far and away the highest rate of confirmed COVID-19 cases.

The state’s smallest county by population, Menominee County, is unique in that it overlaps with the reservation held by the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin. The county’s health outcome rankings have shown a persistent struggle with multiple health-related challenges. The local experience with COVID-19 mirrors other disparities, and on a per capita basis, Wisconsinites who are Native Americans have died from the disease at higher rates than people from any other racial or ethnic background.

For epidemiologists like UW-Madison’s Ajay Sethi, the divergent patterns — with St. Croix and Dane counties as one example and Menominee County as another — point to factors beyond age as driving local COVID-19 impacts.

“It’s not just being of that age,” Sethi said. “If I were 65 or 70, because of my lifestyle I feel very confident that I can avoid getting COVID. I can work at home … I can protect myself. When you’re talking about places where that’s less possible and that overlaps with age, and it overlaps with underlying health conditions, then you’re talking about a lot of factors operating that are going to drive that death rate up.”

The underlying health of communities is indeed one factor local public health officials suspect could be helping drive COVID-19 outcomes in their communities.

“St. Croix County continuously on an annual basis is one of the healthiest counties in the state of Wisconsin,” said Kelli Engen, the St. Croix County health officer.

Engen pointed to the 2020 Wisconsin county health ranking published by the UW-Madison Population Health Institute showing St. Croix County ranked first among the state’s 72 counties for health outcomes in 2020. Dane County, also perennially among the healthiest in the state, ranked 12th in 2020.

“The county health rankings is just one dataset to look at,” Engen said. “[But] I think that it absolutely does matter.”

Janel Heinrich, the public health director in Dane County, also pointed to the county’s health outcomes as likely playing a role in mitigating COVID-19’s local impact.

“We have overall good health outcomes in Dane County, which gives us a bit of an advantage,” she said.

Interventions

Epidemiologists continue to study the impacts of different public health interventions on COVID-19 transmission, but there is a strong consensus among public health experts that interventions including physical distancing, proper mask use and quarantining after exposure (and isolating after developing symptoms or testing positive) effectively dampen transmission.

The Republican majority in both chambers of the Wisconsin Legislature, which has regularly been aligned with a conservative majority on the state Supreme Court on pandemic-related lawsuits, have often expressed opposition to statewide public health orders declared by the administration of Democratic Gov. Tony Evers. And while state Republican leaders have argued that local communities are best positioned to mitigate COVID-19, they have also questioned local health orders that close schools, businesses or places of worship.

Public health officials in Dane County have been undeterred by these politics, and have been among the most vigorous in Wisconsin in terms of setting local restrictions aimed at curbing community transmission of the coronavirus.

Janel Heinrich, the Dane County public health director, said her agency has sought to target its various orders over the course of 2020 and 2021 at the types of places where data showed community transmission was occurring.

“We have such a connection to data, and … we use that to support policy response interventions here that are scientifically driven,” Heinrich said.

Beyond health orders, another factor that can affect local transmission is the willingness of local residents to take up protective behaviors like mask wearing and physical distancing on their own. While solid evidence on the prevalence of these behaviors is scant, local officials in Olmstead County, Minn., speculated that the local workforce and culture there — dominated by the massive Mayo Clinic healthcare campus in Rochester — have had some impact on that area’s relative success in keeping the disease at bay.

Home to the UW-Madison campus and multiple large hospitals, it’s possible that Dane County may benefit from a similar dynamic, Heinrich acknowledged.

“We have a wealth of health care institutions,” she said. “And the university, I think, also has a bit of an influence as well in our adherence to science and our understanding [and] commitment in that shared cultural space.”

Despite some high-profile disagreements between UW-Madison and Dane County Executive Joe Parisi over the return of students to campus in the fall of 2020, Heinrich said the local health department has “a very strong relationship” with the university.

“We do not have policy authority over the university, but there is a desire and intent to be as aligned in policy practice on the institution as we are across the community,” Heinrich said.

Meanwhile, in St. Croix County, Kelli Engen said the local health department has not enacted the types of pandemic orders issued in the state’s second largest metro area.

However, Engen said the county’s ties to the Twin Cities have created a unique situation where differences in pandemic restrictions between Wisconsin and Minnesota are likely playing a role in local transmission. Helping the situation, in her view, is the fact that so many county residents work, shop and seek health care in Minnesota, where she said enforcement of health orders like the state’s mask mandate is more stringent. On the other hand, Engen said bars and restaurants in St. Croix County have at times become popular dining and drinking destinations for Minnesotans seeking to skirt their state’s restrictions.

Engen said she viewed St. Croix County’s proximity to the Twin Cities as a net positive in terms of COVID-19, pointing out the vast difference between her county’s case and death rates and those seen in several suburban counties around Milwaukee.

“We definitely resemble people more influenced by what’s going on in Minnesota,” she said.

That interstate cultural relationship may become all the more important as the Wisconsin Legislature seeks to overturn any statewide public health orders left standing.

With legislative actions against Wisconsin’s mask mandates, those localities with more robust public health restrictions, like Dane County, would be left to defend and enforce their own policies, while the fortunes of border areas like St. Croix County would continue to be tied to the policies of the neighboring state.

A year into the public health crisis, local efforts to keep COVID-19 at bay are occurring amid a race to vaccinate Americans as more virulent variants emerge and pandemic fatigue intensifies.

“In Dane County, like the state and much of the nation, folks are tired and they’re fatigued by this pandemic,” said Heinrich. “That is a challenge. We’ve become normalized as a community to higher rates of illness … that’s a concern we’ve had from the beginning, [and] I think it’s going to be a bigger concern moving forward.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us