A Wet Decade Shifts To Drought In Southern Wisconsin

Following the state's wettest decade on record, lower-than-normal precipitation in the spring of 2021 is leading drought conditions to emerge in agricultural areas reliant on steady rains.

June 7, 2021 • Southeast Region

The grass is green, but dry weather is widening cracks in packed soil along a footpath at Blue Mounds State Park in southwestern Wisconsin. (Credit: Kristian Knutsen / PBS Wisconsin)

A dry spring is steadily giving way to an arid summer as months of below normal precipitation so far in 2021 cause drought conditions across broad swaths of southern and western Wisconsin.

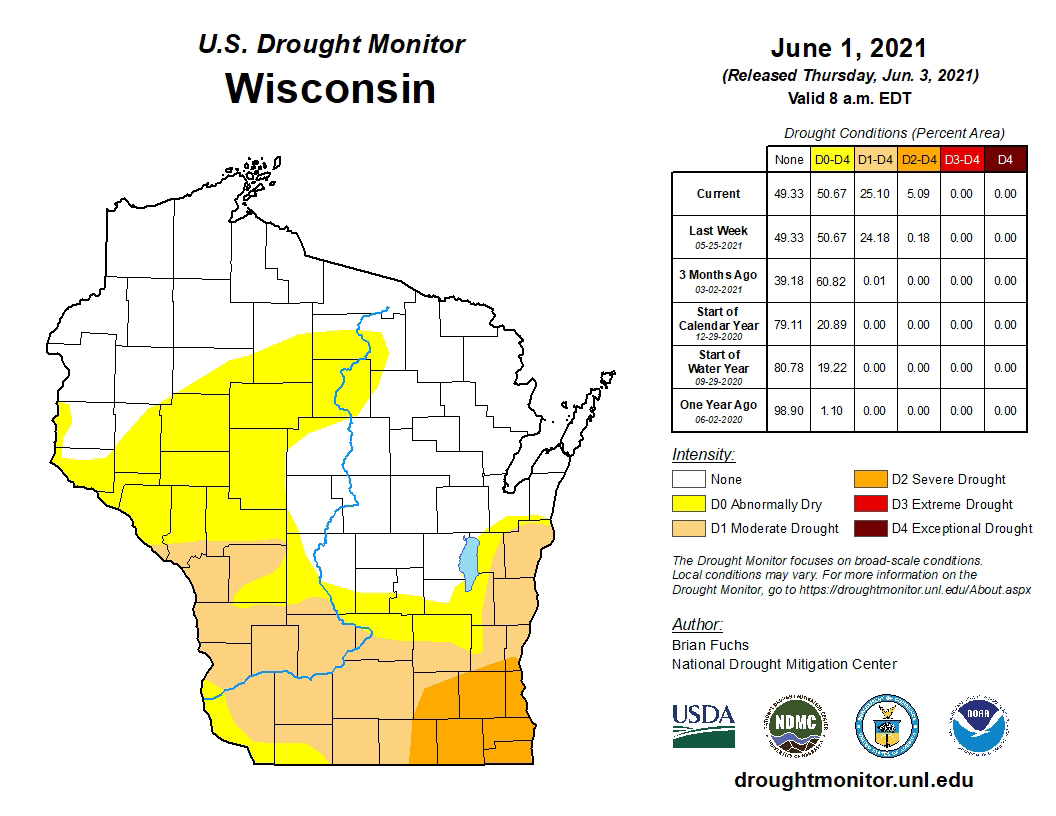

In a June 3 update for Wisconsin, the U.S. Drought Monitor indicated severe drought in the state’s southeastern corner, with moderate drought across its southwestern and east-central stretches and abnormally dry conditions present in adjacent areas and reaching into west-central and north-central portions of the state.

According to this service, a partnership of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration based at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, increasing intensity of drought conditions can have meaningful effects on agriculture and water availability. Moderate conditions may lead to some damage for crops and pastures, with lower water levels in streams, wells and reservoirs and the potential for voluntary use limits. Meanwhile, the possible impacts of severe conditions include likely crop and pasture losses, with water shortages common and restrictions imposed in response.

Based on data as of June 1, 2021, the U.S. Drought Monitor reports abnormally dry and moderate drought conditions across much of southern Wisconsin, with severe drought reported for the state’s southeastern corner. (Credit: U.S. Drought Monitor)

Dry conditions have been holding pretty steady for the past month or so, said Christopher Kucharik, a climate researcher and professor of agronomy and environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The longer they continue, though, the more intense drought becomes, with southeast Wisconsin moving from a moderate to severe level as June started and hot weather descended.

“We’re running a three to seven-inch deficit of precipitation going back to springtime, and that’s equivalent to an entire month to month-and-a-half of rainfall. It’s difficult to make up that type of deficit,” Kucharik said.

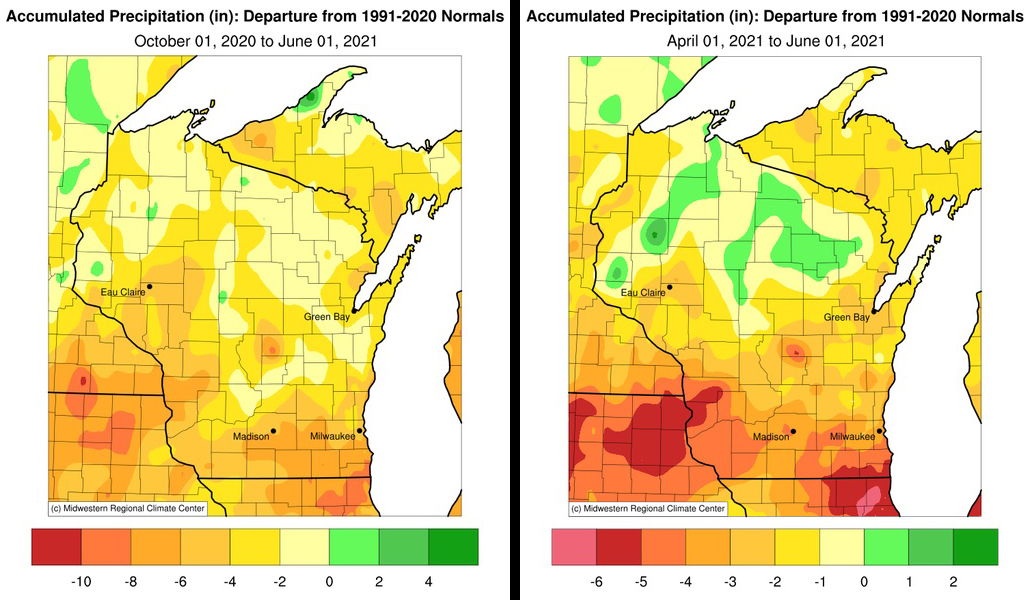

As dry as southern Wisconsin is becoming, conditions remain better in the northern part of the state. The portions north of a line running roughly between the Twin Cities and Green Bay — or the Hwy. 29 line often used as one shorthand for categorizing “up north” in southern Wisconsin — remain clear of moderate or severe drought as of the start of June thanks to higher precipitation levels over the past couple of months. That said, over the past eight months, nearly all of the state has been below normal for total precipitation, according to a drought update issued by the National Weather Service office in La Crosse.

From October 2020 to June 2021, most of Wisconsin had total precipitation amounts below normal precipitation levels over the previous 30 years. For the two-month period from April 1 to June 1, 2021, though, some portions of northern Wisconsin had higher than normal precipitation. (Credit: National Weather Service-La Crosse)

Those differences are expected, said Kucharik.

“I think this is pretty typical of how a lot of growing seasons go across not just Wisconsin but across the whole Corn Belt, or Midwest and Great Plains,” he said. “Every year, someone takes their turn as to having a significant deficit of precipitation and drought.”

For farmers in southern Wisconsin, it’s their turn in the kiln, and adapting to less rain is no simple matter. Irrigation is a common practice (and controversial due to the use of high-capacity wells) in the Central Sands region where potatoes and other vegetables are grown, but it’s a different matter in the grain-growing and dairy-oriented areas to the south.

Kucharik noted most farmers in the southern half of the state don’t have irrigation equipment. “They generally don’t need it because we usually get enough rainfall in this region to support crop growth and end-of-season yields,” he said.

Nor is it simple for farmers to pivot to start irrigating.

“You just can’t go out and get that equipment and get a permit to pump a high-capacity well,” Kucharik added.

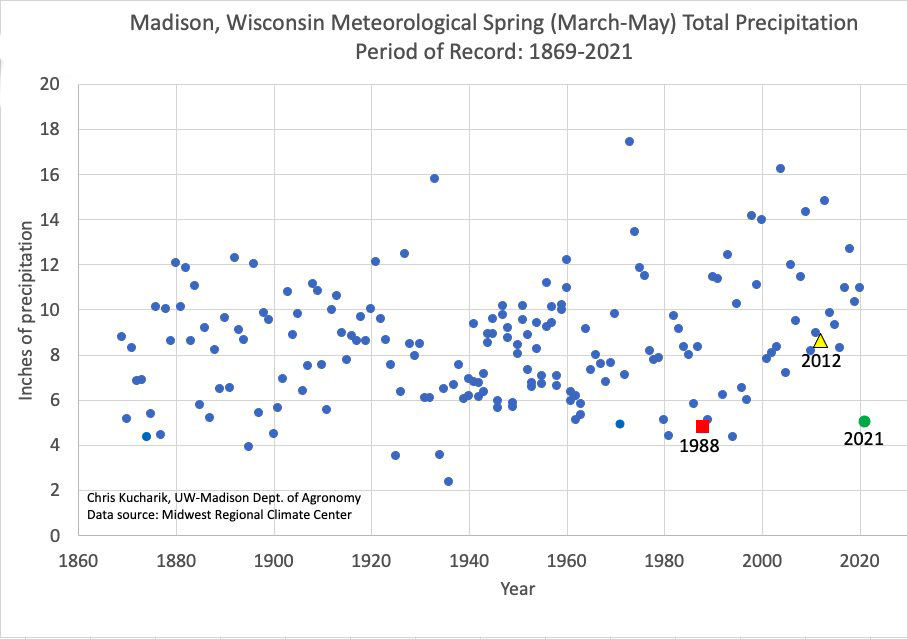

It’s been nearly a decade since a serious drought last struck Wisconsin in 2012, which affected wide swaths of agricultural lands across the Great Plains and Midwest. In turn, those conditions elicited comparisons to a devastating drought in 1988 and 1989 (which was associated with La Niña water temperature conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean, which had also been in place over the 2020-21 winter).

Using data from the Midwest Regional Climate Center, Kucharik examined precipitation levels between March and May for Madison going back to the beginning of record-keeping in the 19th century. With 5.05 inches of precipitation in Madison, 2021 was the 12th driest spring on record going back to 1869. The most recent year that was drier was 1994. By comparison, the March-May total in 1988 was 4.77 inches and in 2012 was 8.65 inches.

Total precipitation between March and May in Madison was at its lowest level in decades for 2021, with a measure several inches below the drought year of 2012 and comparable to levels in the drought year of 1988. (Credit: Christopher Kucharik / University of Wisconsin Department of Agronomy)

Kucharik emphasized that each drought has its own timeline.

“The recent one in 2012 had a much wetter spring than we have had so far this year, so the onset of that drought was about a month later,” he explained. “It didn’t start to take hold until June or early July.”

That difference is one of Kucharik’s concerns about the potential impact on agriculture in 2021.

“People will look back and say crops did better than people were anticipating [in 2012], but there’s a lot less moisture in the soil [in 2021],” he noted. “I think impacts of this drought could happen quicker and be more severe given the time of year it’s happening, when crops are going through their most rapid development stage.”

However summer precipitation unfolds, Wisconsin is experiencing weather whiplash. The 2010s were the state’s wettest decade on record, while 2019 was the wettest year on record, with extreme precipitation causing severe flooding in multiple parts of the state. Farmers have always had to deal with weather variability, but Kucharik notes rapid shifts of this type are what climate research projects to become more commonplace in the future.

“Now we’ve flipped a switch, and these are the types of increased variability that coincides with what we think a changing climate will bring, not just to Wisconsin but to the Midwest and agricultural regions of the central U.S.,” he said. At the same time, the western part of the nation continues to bake as its historic drought intensifies.

More details about impacts of 2021’s drought conditions in Wisconsin are available from the National Integrated Drought Information System.

The uncertainties of week-to-week weather in the Midwest means Wisconsin could experience another shift on short notice, and there is potential for rain in the short-term forecasts for different parts of the state. However, what may feel just like a dry spell will require more than a brief shower here or there to remedy.

“I think things aren’t going to get better any time soon without some pretty significant precipitation,” said Kucharik. “This isn’t going to go away with a couple of days of rain.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us