Wisconsin asylum seeker detained in unprecedented wave of courthouse arrests

Three years ago, a brother and sister crossed the border days apart and asked for asylum. Now she has a green card and he’s in an ICE prison.

Wisconsin Watch

June 24, 2025 • South Central Region

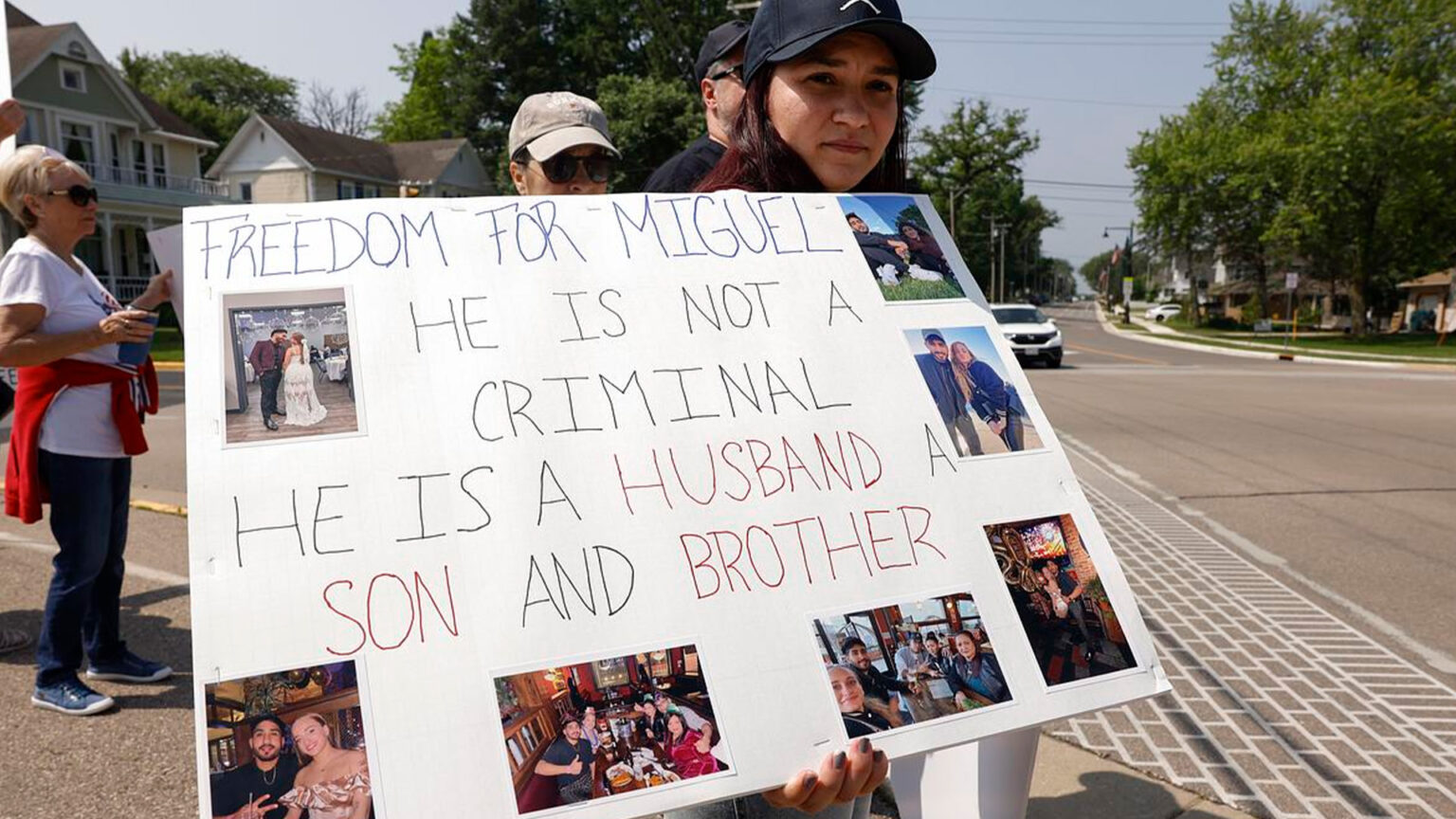

During the No Kings protest in McFarland, Vivianne Jerez holds a sign about her brother, Miguel Jerez Robles, a McFarland resident and asylum seeker who was detained by immigration officers at a Miami courthouse in May. (CREDIT: Ruthie Hauge / The Cap Times)

When McFarland resident Miguel Jerez Robles boarded a plane to Miami last month, he thought he’d be attending a routine immigration hearing about his asylum application and enjoying a rare vacation with his wife and mother.

The 26-year-old and his family had come to Wisconsin in 2022, fleeing political persecution from the Cuban government. They moved to the village just outside Madison, home to a friend his brother-in-law met while driving a taxi in Santiago de Cuba.

Jerez rented an apartment near the high school and got a job delivering packages all over southern Wisconsin, first for FedEx and later for an Amazon subcontractor. He and his wife started a popular YouTube channel, Cubanitos en la USA, where they shared videos about what it was like to work as a delivery driver, buy a car or shop for groceries in Wisconsin.

The Florida trip was Jerez’s first vacation since arriving. Jerez planned to go to the May 22 preliminary hearing in his asylum case, then take his family to the beach and explore the city.

Instead, immigration authorities arrested Jerez and sent him to a detention center, sweeping him up in what appears to be a coordinated strategy to fast-track deportations.

When Jerez appeared in the Miami courtroom, a federal attorney asked the judge to dismiss his asylum claim. According to Jerez’s family, the judge agreed without explanation, then wished him luck.

Jerez headed to meet his wife, Geraldine Cruz Dip, and his mother, Celeste Robles Chacón, who were waiting just outside the fifth-floor courtroom.

Miguel Jerez Robles and Geraldine Cruz Dip met while working at a Chinese restaurant in Santiago de Cuba, Cuba. They came to the United States seeking asylum in 2022 and married in Fitchburg in 2023. (Credit Geraldine Cruz Dip and Miguel Jerez Robles)

Plainclothes Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents were waiting too. They handcuffed and arrested him before he could reach his family, his mother said.

Three days later, Jerez was shackled and flown to a detention center in Tacoma, Washington, through a process called expedited removal, which allows the government to deport certain immigrants without first hearing their cases in court.

His wife and mother returned home to McFarland alone.

“The vacation turned into a nightmare,” Cruz said. “Everything fell apart in a moment.”

Jerez was among the first people swept up in a recent wave of arrests inside immigration court buildings, a place considered off limits for such enforcement until the Trump administration loosened restrictions earlier this year. Some, like Jerez, report judges unexpectedly dismissing their cases in what some immigrants and attorneys believe is a coordinated effort to quickly detain large numbers of people as soon as they lose legal immigration status — including those who, like Jerez, have no criminal history.

“It’s easier to go to a courthouse and pick up everyone there than go searching for them at home,” Cruz said.

These arrests, which appear to have begun in late May, are part of President Donald Trump’s sweeping immigration crackdown, some of which he promised on the campaign trail. The scale and methods reach far beyond what many expected from an administration that has vowed to prioritize removing people who threaten public safety. Recent ICE raids at schools and other sensitive locations have sparked multi-day protests in Los Angeles and other major cities.

For asylum seekers like Jerez, who followed steps laid out by the previous administration, the policy shift means they’ll now likely have to make their cases from behind bars.

His story illustrates the volatility and randomness of the country’s immigration processes. Had Jerez arrived five years earlier, before President Barack Obama ended the “wet foot/dry foot” policy that applied to Cuban immigrants since the 1960s, he and his family would have immediately qualified for legal status and a pathway to citizenship. And if he’d only been given the same paperwork as his sister — who arrived for the same reasons just days later — he may have a green card today like she does.

Attorneys: Judges and ICE collaborate in courthouse arrests

Jerez’s arrest shocked his attorneys too. For much of the past two decades, officials reserved the expedited removal process for immigrants arrested near the border within two weeks of arriving in the country.

Former President George W. Bush first implemented these guidelines in 2004. However, during his first term, Trump expanded use of expedited removal procedures to include immigrants anywhere in the United States who have spent less than two years in the country. Former President Joe Biden rescinded that expansion, only to see Trump restore it in January through one of the first executive orders of his new term.

People who are convicted of certain felonies can face expedited removal outside of normal parameters.

“But these people, they are clean. They have no crimes, no record, no nothing,” Ismael Labrador, an attorney with Miami-based Gallardo Law Firm who is representing Jerez, said of those affected by Trump’s latest tactics.

Jerez has been in the country longer than two years. But the Trump administration argues expedited removal should apply to similarly situated immigrants, as long as immigration authorities processed them within two years of their arrival.

“He had everything in order, and he was arbitrarily arrested and placed in expedited removal when he doesn’t qualify to be in expedited removal,” Labrador said.

Geraldine Cruz Dip, left, and Vivianne Jerez show a screenshot they took during a video call with their husband and brother Miguel Jerez Robles, who’s been detained at the Northwest Detention Center in Tacoma, Washington, since May. They say detention has made him depressed. (CREDIT: Ruthie Hauge / The Cap Times)

The American Civil Liberties Union of New York sued the Trump administration in January, arguing Trump violated the rulemaking process and the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause in expanding the scope of expedited removal.

Now, the administration is further accelerating removals by dispatching ICE agents to courthouses to immediately arrest following the dismissal of immigration cases.

Labrador isn’t surprised immigration judges, government attorneys and ICE agents appear to be collaborating on the plan. While the federal government’s judicial branch houses most judges, immigration judges are part of the executive branch, employed by the Department of Justice.

“They work for the same boss,” he said, referring to Trump.

In light of the new practice, the nonprofit National Immigration Project recommends immigration attorneys consider requesting virtual hearings to protect clients from courthouse arrest.

The group released that guidance in May, just a week after Jerez’s arrest.

“Unfortunately, if I remember correctly, he was imprisoned on the second day this new (courthouse arrest) strategy had begun,” Labrador said. “It was a surprise to all of us.”

Some of Labrador’s other clients have been detained in similar ways, prompting him to begin requesting virtual hearings.

He followed the rules. Then the rules changed.

Jerez sought asylum in the United States after mass demonstrations in his homeland in 2021, when people in dozens of Cuban cities took to the streets to protest shortages of food and medicine, as well as their government’s strict response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jerez had spoken out against Cuba’s communist government and refused to perform his mandatory military service, putting him and his family in the crosshairs of the authorities, Cruz said. She recalled a time when police interrogated him for six hours and broke his cellphone.

“They told him that the same thing would happen to us as to that phone,” Cruz said. Another time, she said, the police chief came to the family’s home ahead of another round of protests and told them that if they wanted to live, they’d stay home.

The couple lost their jobs at a Chinese restaurant, she said, after police threatened to shut it down if they weren’t fired. The pressure wouldn’t let up, Cruz said, so Jerez and three family members flew to Nicaragua in separate trips and then spent two months traveling by land to the U.S.-Mexico border.

Jerez and his family followed all the government’s requirements while pursuing permanent legal status, his immigration attorneys said.

That included presenting themselves to Border Patrol agents and requesting asylum when they arrived in Nogales, Arizona, in 2022. Jerez was handed an immigration form called an I-220A, allowing immigrants to be released into the United States as long as they stay on the government’s radar — following certain rules and appearing at all court hearings.

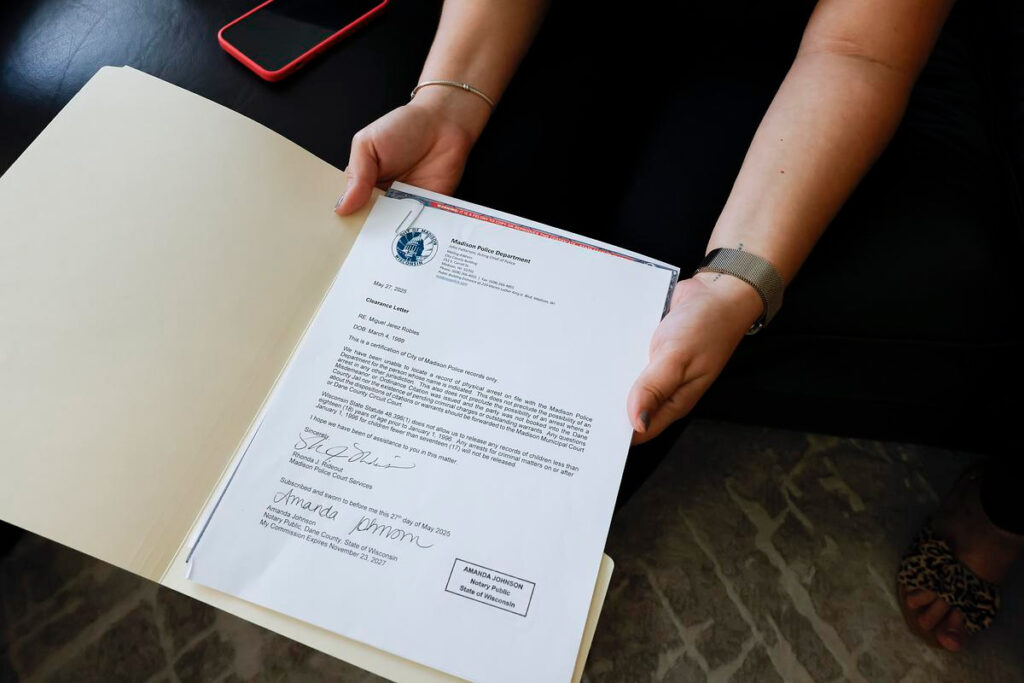

- Vivianne Jerez, sister of Miguel Jerez Robles, holds a letter from the Madison Police Department verifying that her brother has no criminal record in the jurisdiction (CREDIT: Ruthie Hauge / The Cap Times)

- Celeste Robles Chacón, mother of Miguel Jerez Robles, was waiting for him outside his asylum hearing when he was arrested by plainclothes immigration enforcement agents. (CREDIT: Ruthie Hauge / The Cap Times)

After the family settled in McFarland, Jerez drove to Milwaukee every year for a check-in with immigration agents. He never missed an appointment, his wife said. The government issued a work permit that authorized him to work in the U.S. until 2029.

In 2023, Jerez’s sister Vivianne received a green card, making her a permanent U.S. resident. That’s because she received different paperwork upon her release at the border. It placed her on humanitarian parole, which provides temporary legal status to people from certain countries.

The 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act allows Cubans to apply for permanent residency after having lived in the United States for more than a year. But Jerez was not eligible while his asylum case was pending in immigration court. The U.S. Board of Immigration Appeals ruled in 2023 that immigrants with I-220A status could not apply for green cards.

Meanwhile, a Trump executive action ended humanitarian parole for people arriving from a slew of countries, including Cuba.

Border agents’ choice to nudge a brother and sister toward divergent immigration pathways appears to be random, the family said. That fits a trend, said Labrador, as border agents receive little to no guidance — and wide discretion — on what paperwork fits each situation.

Seeking asylum a second time

Once in expedited removal proceedings, immigrants can be immediately deported unless the government determines they have “credible fear” that they would be persecuted in their home country because of their political views or identity.

On June 12, guards at the Northwest ICE Processing Center in Tacoma told Jerez to get dressed to go to the library, his sister said. When he got there, he learned this would be his official interview about why he’s afraid to return to Cuba — determining whether he’ll get a chance to bring his asylum case.

No one has told Jerez when he’ll learn the result, Cruz said, so she asked ChatGPT.

“It says it takes three to five business days, so I think it would be this week,” Cruz said in a June 17 interview. As of Friday, she was still waiting for news.

Based on Labrador’s experience, it can take up to a month.

If Jerez passes the interview, his lawyers will file a second asylum application. But that wouldn’t prompt Jerez’s release.

“He will have to defend his case in custody, unfortunately,” Labrador said.

Jerez’s mother calls uncertainty “psychological torture” for detainees.

Guards have offered Jerez and other detainees the chance to sign papers consenting to be deported, Cruz said.

“From the time they arrest them, the first thing they say is, ‘Sign this and you’ll go to your home country, or prepare to be detained here for up to two years,’” Cruz said.

Jerez and his family are still trying to understand why the government detained him after he did everything it asked, including attending immigration and court appointments, working and paying taxes.

“He doesn’t have so much as a traffic ticket,” his sister, Vivianne, said.

But they know he’s not alone. On TikTok, they see one woman after another “crying because they took their children or their husbands,” Cruz said.

They know others who voted for Trump, thinking he’d only deport criminals, only to have their loved ones detained too, Cruz added.

“He just wants white Americans who speak English when really Latinos are this country’s main workforce,” she said. “If they said they were going to search for people with criminal records, why are they arresting people who don’t have any kind of criminal record?”

In a recent New York Times interview, Trump’s border czar, Tom Homan, claimed the administration is prioritizing “the worst first” for deportation but acknowledged other immigrants may get swept up in the fray.

“We’re prioritizing public safety threats, people who have committed crimes in this country or who have committed crimes in their home country and came here to hide,” Homan said. “But I’ve also said from Day One, if you’re in the country illegally, you’re not off the table.”

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement did not respond to questions about Jerez’s detention.

‘A total disaster’

To talk to his family from the Tacoma detention center, Jerez waits his turn to make video calls on a tablet shared by around a dozen detainees.

On those calls, he usually looks sad, Cruz said. She thinks detention has made him depressed.

Labrador also tries to speak with Jerez as often as possible. The conditions at the facility, one of the country’s largest, are “a total disaster,” he said.

“They are sleeping on the ground. They are being moved constantly. They are waking up in the middle of the night for (head) counting,” he said, adding that fights occur regularly and detainees get little to no medical treatment.

But Jerez’s mood was better last Saturday. When he called his family that day, his sister had just returned from protesting the Trump administration at the “No Kings” rally in McFarland, where she’d carried a hand-written sign covered with family photos .

“Freedom for Miguel,” it read. “He is not a criminal. He is a husband, a son and brother.”

He smiled as they showed him photos and told him about the people who approached her to express sympathy or outrage. Some hugged her and cried. Some said they would pray for her brother.

Cruz saved screenshots from that call. In the three weeks since his detention began, Vivianne said, it was the first time she’d seen him looking happy.

Andrew Billmann, the friend her husband met in his taxi years before, protested alongside Vivianne Jerez, carrying a sign that included a QR code with more information about the detention.

During the No Kings protest in McFarland, Andrew Billmann spreads the word about his friend, McFarland resident Miguel Jerez Robles, a Cuban asylum seeker who was detained by immigration officers outside his immigration hearing in Miami. (Credit Ruthie Hauge / The Cap Times)

“This is not someone that snuck in. This is not someone who’s trying to conceal their location. He’s been completely forthcoming from the beginning,” Billmann said in an interview.

Billmann and his wife, Kathy, have helped the family settle in McFarland, find housing, set up bank accounts and stay on top of their immigration paperwork.

“They’ve literally done everything right,” Billmann said. “I helped Miguel get his driver’s license. He’s got a Social Security number, a work permit. This is all as it’s supposed to go.”

Instead, the arrest has upended life for the whole family. Vivianne canceled her June 9 wedding ceremony. That cost the couple $1,000, but they couldn’t stomach trying to celebrate. Their loved ones cried as the couple quietly signed their marriage license at the McFarland apartment they share with her mother.

And now? The family waits.

Vivianne, who worked as a doctor in Cuba, recently finished training to become a U.S. registered nurse. Her graduation photo sits in her living room, but she hasn’t celebrated that feat either. On the coffee table sit the now-shriveled roses Jerez gave his mom for Mother’s Day. She can’t bring herself to throw them out.

On the couch, Cruz sorts through the evidence she’s marshaled as proof of her husband’s good character: the letter from the Madison Police Department saying he had no record with the department, the awards he received from his delivery jobs, the letter in which his boss called him “an exemplary employee” and said he was “praying for his eventual return.”

Geraldine Cruz Dip, Vivianne Jerez and Celeste Robles Chacón discuss the status of their family member, Miguel Jerez Robles, a Cuban immigrant and refugee, who was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers after a scheduled immigration court hearing in Miami. (CREDIT: Ruthie Hauge / The Cap Times)

Cruz, who drives for the same company, has continued delivering Amazon packages to pay the bills.

Billmann set up a GoFundMe page where community members can donate money to help Cruz cover living expenses while her detained husband can’t work.

If the court gives Jerez another chance at release, she plans to use that money to pay his bond.

“They’re just wonderful, wonderful people,” Billmann said. “It’s just absolutely crazy what they’re putting this family through.”

The story was co-produced by The Cap Times and Wisconsin Watch. This article first appeared on Wisconsin Watch and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

![]()

Passport

Passport

Follow Us