Southern Wisconsin's Ghost Towns Leave Behind Vital Stories

Wisconsin's roots as a state are found in a patchwork of scrappy independent settlements, interspersed with the occasional fraudulent land scheme.

September 9, 2016

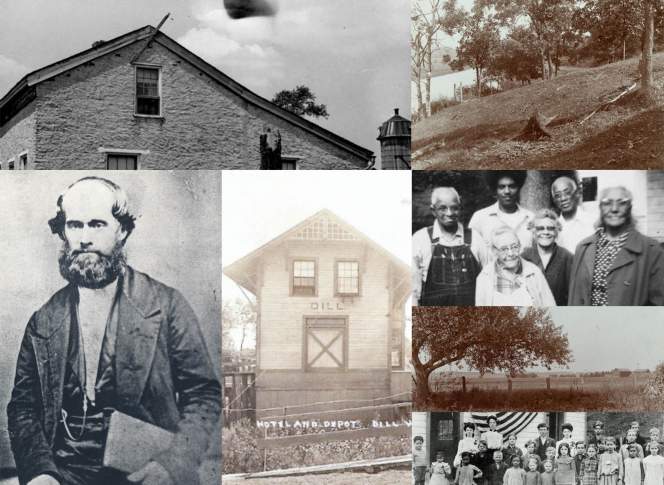

Collage of photos from lost towns of southern Wisconsin

Wisconsin’s roots as a state are found in a patchwork of scrappy independent settlements, interspersed with the occasional fraudulent land scheme. Around the creation of Wisconsin Territory in 1836 to the end of the Civil War in 1865, newcomers to the region established many towns across what is now the southern part of the state. These immigrants’ fortunes often depended on the location of natural resources and related placement and building of railroad routes.

As the economy of the Midwestern U.S. took shape, though, some of these new settlements by people of European (and in a couple cases African) descent later disappeared from the map. There is little left to visit of these places, but many could give New Glarus or Mineral Point a run for their money when it comes to rich and colorful history.

Wisconsin-based author and historian Kim Tschudy has spent years uncovering the traces of these often short-lived communities and the people who built them. A New Glarus native, he has written several books about Wisconsin history, including one on the settling of Green County. Tschudy offered a survey of several in an October 28, 2014, talk at the Wisconsin Historical Museumin Madison, recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

In his talk, Tschudy shared individual stories from several ghost towns, including places once known as Voree, Cheyenne Valley and Gratiot’s Grove. He also offered some bold strokes about the 19th century cultural and economic forces that helped to create and eventually dissolve these communities. Some of these settlements are less-appreciated landmarks in America’s complex racial and ethnic history — and many were colorful, wild, and even downright tragic during their short lifespans.

Key facts

- For many abandoned settlements in southern Wisconsin, all that remains are graves and/or cemeteries, and maybe a historical marker. Sometimes, their buildings were moved to their present-day locations in other towns.

- Many settlements’ fates were sealed by the building of railroads. Some were built along a railroad track that was later diverted elsewhere. Others were built in anticipation of tracks being built nearby, but dissolved when railroad builders picked a different route.

- A few of southern Wisconsin’s lost towns, like Gratiot’s Grove in Lafayette County, were founded as lead-mining and -smelting settlements, but vanished as the supply of lead dwindled.

- Henry Gratiot’s house in Gratiot’s Grove is still standing and is the second-oldest home in Wisconsin. (It’s now Gratiot House Farm Bed & Breakfast, opening in the summer of 2016 after a six-year restoration process.)

- Pleasant Ridge in Grant County and Cheyenne Valley in Vernon County had largely African-American populations and some of the first integrated schools in the United States. Wisconsin’s defiance of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Acthelped these towns get started. Their founders and early residents included escaped or freed slaves and even plantation owners who’d grown concerned about their former slaves’ well-being.

- Sinipee, located along the Mississippi River in Grant County, was first settled in 1832. The community went under in a malaria outbreak at the end of the decade. Melting snow formed puddles that became breeding grounds for mosquitoes, which spread the disease and killed off a large part of the town’s population.

- Belmont in Lafayette County was formed when Galena, Illinois-born John Atchison attempted to found a capital city for the Wisconsin Territory. But when the territorial legislature convened there in 1836, the buildings had not been completed, and members were forced to sleep on the floor of one of the buildings wrapped in their coats. This debacle inspired a speculator named James Doty to establish Madison as the capital. (The First Capitol is now an educational site operated by the Wisconsin Historical Society.)

- Mormons established some now-vanished settlements in southern Wisconsin during the mid-19th century, including Zarahemla, on the site of present-day Blanchardville near Yellowstone Lake State Park in Lafayette County, and the especially ill-fated Voree, also known as “The Garden of Peace,” in Walworth County.

- Exeter in Green County had its own women’s tug-of-war team.

- Ulao in Ozaukee County was a childhood home of President James A. Garfield’s assassin, Charles Julius Guiteau.

- The photo collage at top includes several images from Tschudy’s presentation. Clockwise from bottom left, they are: James Jesse Strang, Mormon sect leader and founder of Voree; Strang’s house in Voree; a hill in Voree; residents of Cheyenne Valley’s integrated population; a field in Voree; teachers and students at Cheyenne Valley’s integrated school; and a hotel and railroad depot in Dill.

Key quotes

- Why ghost towns became ghost towns: “New Diggings [in Lafayette County], like so many towns fell victim to the loss of the natural resources, which is a typical strain with almost all of the towns…. Either it was a natural resource boom that they could take and use, or it was the loss of a railroad or the railroad not coming to their town.”

- Reading a statement by a Cheyenne Valley resident summing up the community’s spirit: “Everyone was concerned about their neighbor. We didn’t even know we were integrated. We just didn’t think about color.”

- On the dramatic end of Voree and its founder, James Jesse Strang: “There on 1850, Strang was crowned the king [of the town]. He wore a discarded Shakespeare actor’s red robe and a crown for his coronation. Shortly thereafter, Strang proclaimed that the Lord had commanded him to institute polygamy, which caused a great uproar. Strang’s despotic rule was despised and in the summer of 1856, two of his followers shot and killed him.”

- On Dill in Green County: “The only trace of Dill that you’ll find today is one green road sign that says ‘Dill.'”

- On his favorite Wisconsin ghost town, Centerville, in Green County: “What happened was the town was laid out and speculators that laid out the town had these beautiful drawings of Centerville. They went to Milwaukee, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Philadelphia, selling these lots in this beautiful mecca in southern Wisconsin. These people showed up to claim their lots and the only thing they found were the red surveyors’ stakes. There was never a nail driven there, and the speculators were long gone.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us