Low Risks, High Consequences: CWD Testing And Human Health

The degenerative nervous system disorder chronic wasting disease primarily infects deer, moose and elk in several locations around North America, including in Wisconsin.

November 22, 2016

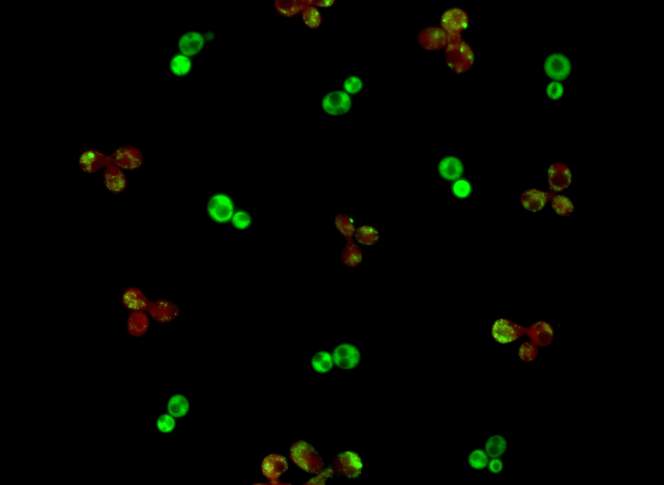

Prion protein clusters in a yeast cell

The degenerative nervous system disorder chronic wasting diseaseprimarily infects deer, moose and elk in several locations around North America, including in Wisconsin. So far the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that “no strong evidence of CWD transmission to humans has been reported.” However, scientists who note the risk to humans is low also admit that the disease could jump the species barrier at some point.

CWD is caused by infectious proteins called prions, a biological material that differs from other disease-causing agents like viruses and bacteria. Multiple prion diseases affect humans, but only one — bovine spongiform encephalopathy, also called “mad cow disease” — is known to date to have crossed over from animals to infect humans. Another prion disease, a spongiform encephalopathy called scrapie, has been known for at least 200 years to infect sheep and goats, but has not infected humans. The best-known prion disease that infects humans is Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, which, like others of its type, is always fatal and tends to kill quickly.

Barbara Ingham, a food safety expert with the University of Wisconsin-Extension, said that for humans, CWD presents a combination of low risk and potentially high consequences.

“There are some more demonstrable risks associated with improper handling of the animal in the field, like the inability to quickly chill the meat, which are more likely and are far higher risk to human health,” Ingham said.

She is more worried about bacteria like Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Clostridium perfringens sickening venison eaters than she is about CWD transforming into a human disease. However, Ingham said people with a family history of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease are at risk of inheriting it genetically, which means they might be more vulnerable to a CWD crossover and should absolutely get their deer tested before eating it.

“There is cause for concern because those are devastating illnesses,” Ingham said. “However when you rank the risk, luckily for us, it is low.”

The CDC recommends avoiding venison from deer that might be infected, and advises hunters to avoid handling certain deer organs, including the spleen and eyeballs. Also, proper cooking isn’t enough to deactivate prions. A beef industry website about bovine spongiform encephalopathy says using an autoclave or incinerating meat at 900 degrees for four hours to deactivate or destroy prions, respectively, procedures that don’t really translate to a venison summer-sausage recipe.

Wisconsin health officials are basically on the same page. A DNR tip sheet about venison and CWD includes a recommendation from the Wisconsin Division of Public Health that “venison from deer harvested in CWD affected areas not be consumed or distributed to others until CWD test results on the source deer are known to be negative.”

Bryan Richards, a Madison-based CWD specialist with the United States Geological Survey, said he thinks this recommendation is in keeping with what public-health agencies like the CDC and World Health Organization promote.

However, he thinks this health message is at odds with the DNR’s approach to CWD testing. There’s no requirement that hunters have their deer tested, even in areas where the disease has been detected. The state does extensive outreach to try and get hunters to submit deer heads, including new initiatives like setting up self-service kiosks and, in 2016, piloting do-it-yourself sampling kits with about 50 hunters, said Tami Ryan, the DNR’s wildlife health section chief.

In Wisconsin, the Wisconsin Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory has the only facility that can test hunters’ deer for CWD — again, that testing depends overwhelmingly on hunters submitting their deer. The lab can handle a lot of volume, and for a fee, it will process samples for hunters who aren’t submitting them through a DNR program. Only about a dozen people per year do that, though, said Pathology Sciences Management Supervisor Dan Barr.

As a result, Wisconsinites maintain a strong deer-hunting tradition but haven’t developed much of a CWD-testing tradition. In 2015, Wisconsin hunters killed a total of 309,829 deer. That same year, 3,142 were tested for CWD. That’s just 1 percent of the state’s deer harvest. The most deer the state has ever tested in one year was 40,148, in 2002 — about 11 percent of that year’s harvest. The state’s goal for 2016 is to test between 4,000 and 6,000 deer.

“I find it interesting that we have this recommendation from human health experts at multiple different levels, a consistent message that if you hunt in an area where CWD is, you should consider having that deer tested,” Richards said. “But is that testing truly available?”

Additionally, not every deer with CWD will show obvious symptoms like emaciation, disorientation and extreme thirst. When a deer is infected, it goes through an 18- to 24-month “pre-clinical” phase where the disease is incubating and the animal looks normal, Richards explained.

“The clinical phase of disease, with behavioral and physical appearance changes, is quite short, from a few weeks to a couple of months before death,” he added.

Even during the pre-clinical phase of CWD, a deer can be “be actively shedding infectious agent,” Richards said.

For a food scientist like Ingham, the outward signs of a disease are important.

“The health of the animal that is harvested by the hunter is the most obvious indication that we have of whether or not the animal should be harvested and the meat consumed,” she said. “That’s the first line of defense.”

The DNR focuses its CWD sampling efforts on areas where the most infected deer have been found and in adjacent areas where it’s likely to spread. From a human-health perspective, Ingham said, that approach is perfectly reasonable and science-based — since DNR doesn’t have the budget to cast a statewide net, it has to make decisions based on risk.

“It’s not prevention; it’s containment,” she said. “With the resources they have, I think the state is managing the disease to the best of their ability…it is not a disease that can be eradicated. History has shown that.”

Richards also credits the DNR and the state lab for the work they do within budgetary constraints. But the lack of momentum behind testing for CWD still worries him.

“We don’t see the push from the state to get deer tested,” he said. “Not like we did during the early years.”

Editor’s Note: This article is corrected to note that bovine spongiform encephalopathy is the only prion disease currently known to have been transmitted from animals to humans.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us