Wisconsin's Role As A Hub In U.S. Flu Surveillance

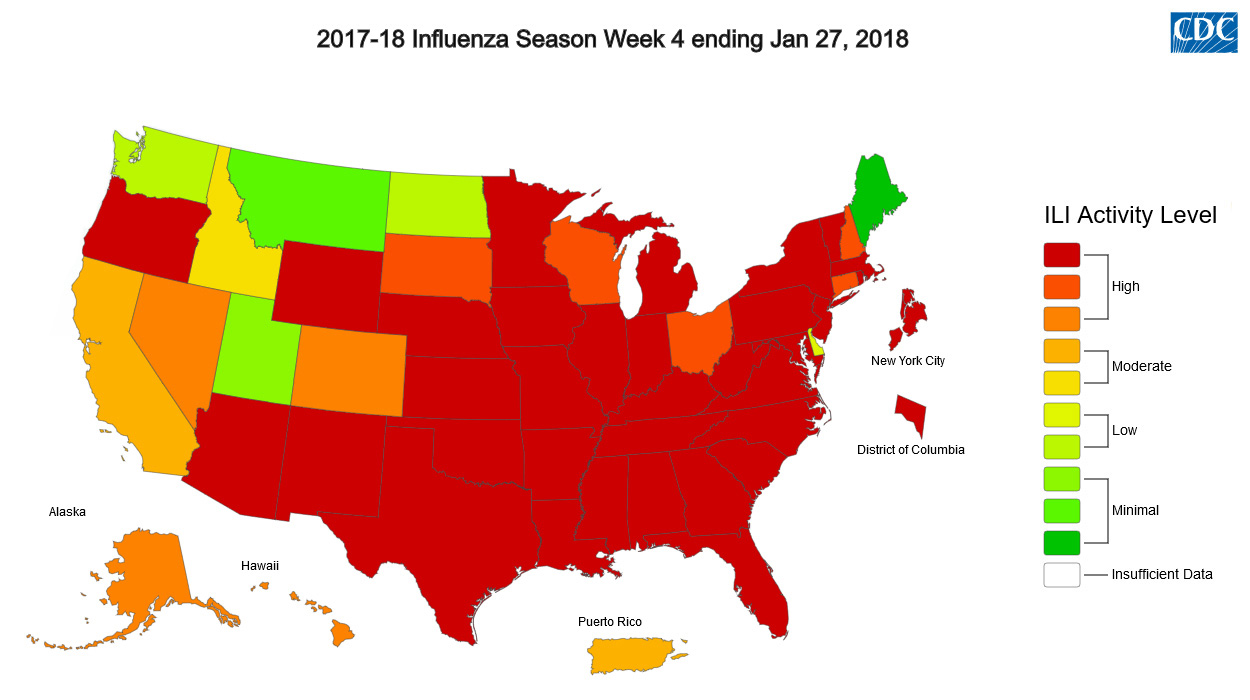

As Wisconsinites push through a hard flu season, public-health officials are following a distinct mix of influenza strains and worrying about the effectiveness of this year's vaccines, but they're also thinking a lot about an intricate disease-tracking network that's been built up over time.

February 6, 2018

Flus label on cooler door at Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene

As Wisconsinites push through a hard flu season, public-health officials are following a distinct mix of influenza strains and worrying about the effectiveness of this year’s vaccines, but they’re also thinking a lot about an intricate disease-tracking network that’s been built up over time.

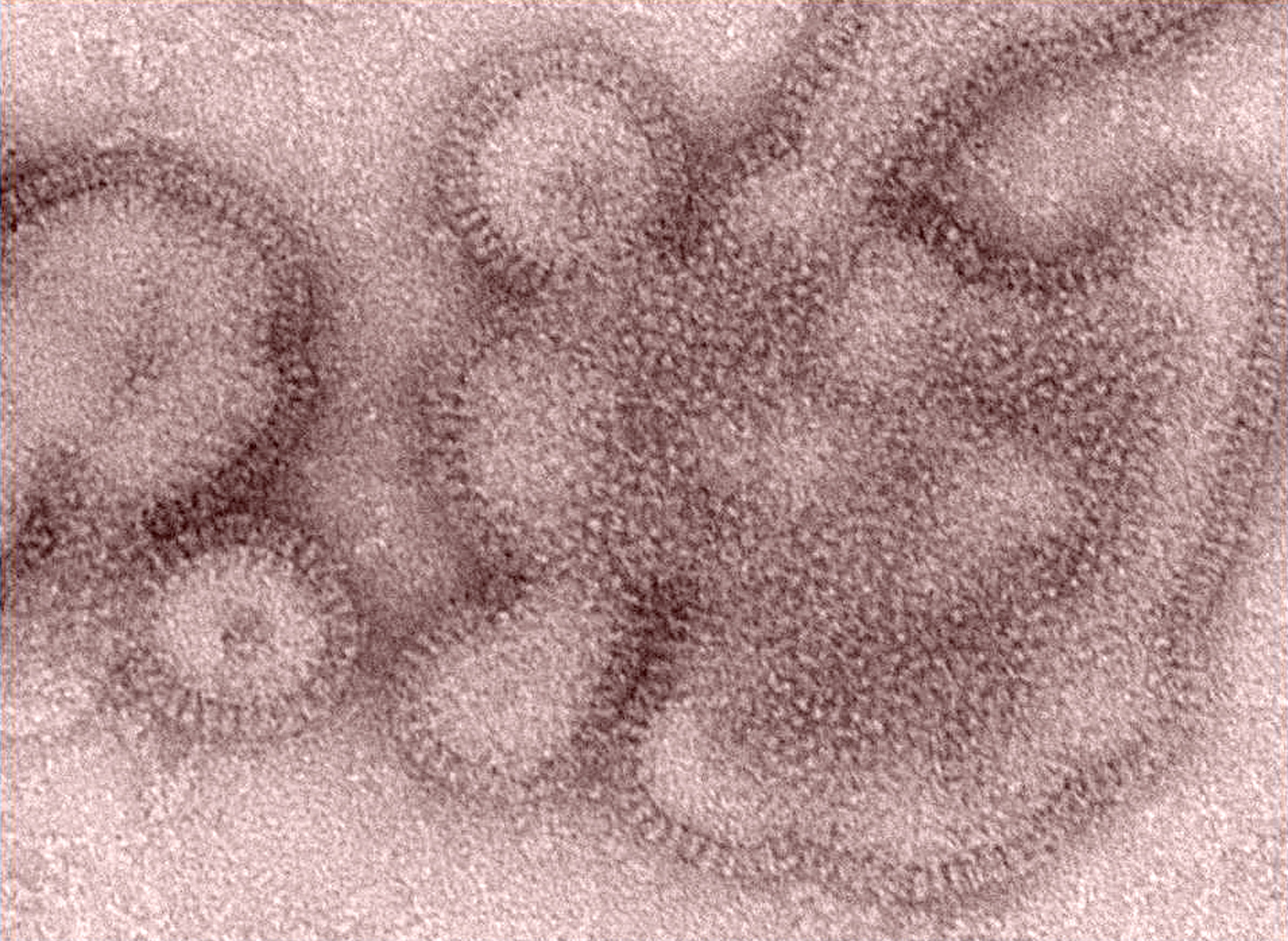

The Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene tracks the prevalence of influenza cases throughout the state, collecting data and viral specimens sent by healthcare providers and public health departments. It’s the job of the lab’s Communicable Disease Division to paint a statewide picture of the flu based on what medical practitioners in local communities are seeing, and to do additional testing on submitted samples to get a better understanding of the types influenza and other respiratory pathogens making Wisconsinites sick. This surveillance helps public-health officials and healthcare providers understand how well flu vaccines are working, and can spot any unfamiliar forms of the flu virus.

Wisconsin also plays a key role in the nationwide monitoring of influenza outbreaks. The state hygiene lab is one of just three state-level institutions in the United States that serve as regional monitoring hubs for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. California, New York and Wisconsin each operate labs designated as a National Influenza Reference Centers, called a NIRC.

Each center gathers and analyzes state-level data from across its respective region; for Wisconsin, that region spans between 16 and 20 states, depending on the changing needs and resources of the CDC and the other regional labs. At the State Laboratory of Hygiene’s testing facilities on the southeast side of Madison, microbiologists often analyze influenza specimens from as far away as Texas.

So far, the 2017-18 flu season has found the lab slammed but not strained.

“We’re busy, but we’re getting out of here at a normal time. We’re not having to go to extra hours like we did during the [2009 flu pandemic] — we essentially became a 24-7 operation,” said Pete Shult, director of state hygiene lab’s communicable disease division.

“We have enough flexibility that we can bolster our staff, not only to carry out our surveillance activities from Wisconsin, but at the same time we’re getting a spike in the specimens coming in as being a NIRC,” Shult said. “We’ve over the years recognized that you need the surge capacity.”

Ongoing flu surveillance is finding that Wisconsin, along with the rest of the U.S., is mostly just getting slammed with the H3N2 subtype, which is particularly aggressive among older adults.

“The hallmark of flu is that it changes from year to year,” Shult said.

Beyond the daily testing and research, the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene relies on building relationships with other public and private medical labs across Wisconsin. There’s also a lot of communication that’s needed to make sure that specimens and data get where they need to be. To that end, the state lab provides various training services and hosts professional conferences for scientists and public health professionals around Wisconsin.

“That’s really the backbone of surveillance. If you don’t have that network, you can’t carry out your surveillance,” said Erik Reisdorf, the state hygiene lab’s virology surveillance coordinator. “You have to be engaged with all the stakeholders all the time.”

Raymond P. Podzorski, a microbiologist with St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison, calls the state hygiene lab “the straw that stirs the drink” when it comes to flu surveillance in Wisconsin.

Even though St. Mary’s is part of a relatively large regional healthcare company and has resources of its own for testing influenza specimens from patients, statewide data is crucial to its flu-season decision-making process. When flu cases are on the rise around the state, the hospital knows to start ordering more influenza testing kits, reaching out to additional manufacturers or distributors if necessary. When all data points to the flu season being at its peak, as it has in early February, that information also influences how practitioners diagnose and treat people with respiratory illnesses.

“Knowing that we’re at peak can impact how providers manage their patients,” Podzorski said. “They may not feel that they need to do tests specifically for influenza. They may decided that they can use clinical signs and symptoms now … and decide to treat with Tamiflu versus trying to diagnose with a laboratory test.”

Public health on soft money

Virologists studying flu specimens in labs are also thinking a lot about building and maintaining relationships with each other and with healthcare providers, and maintaining the funding that supports flu surveillance.

Sharing some of the flu surveillance workload with the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene helps staff at the CDC itself spread more resources to other disease-surveillance activities in the U.S. and abroad. It also brings the state lab a sizable stream of funding.

The Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene is officially a part of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and like just about any of the university’s science-oriented entities, it relies on federal money to a considerable degree. In its 2016-17 fiscal year, the lab received $5 million in federal funding for its communicable disease work alone. As a whole, the lab received $11 million in state funding to support all of its divisions, said its spokesperson Jan Klawitter.

The flu surveillance partnership with the CDC brings in money that helps the state hygiene lab pay for staff and powerful scientific instruments. With this capacity, the lab seeks to anticipate spikes in demand for its services during flu season, and ramp up and reallocate resources as needed. When smaller labs around the state need to send in virus samples for further testing, the state hygiene lab covers the costs of shipping and packaging, and absorbs the cost of a lot of much of the testing without charge.

This capacity built up over time is what makes its service valuable to medical practitioners and disease trackers throughout the state. And from a national point of view, the lab provides an important piece of the broader network that tracks the unpredictable and dangerous influenza virus, both seasonal and pandemic. And that’s only possible if the federal government keeps funding the CDC at levels comparable to what it has in the past.

“Any thought of cutting CDC by a substantial percentage…would cripple our effort here,” state hygiene lab communicable diseases director Pete Shult said of the public debate about federal funding for the CDC.

“Certain things would have to be let go, and that would translate down to us, and there is far from an unlimited pot of money at the state level that could help make up that shortfall. We wouldn’t even be able to do the NIRC activities, because that’s directly funded by the feds. I couldn’t use state tax dollars to be doing testing for Kentucky.”

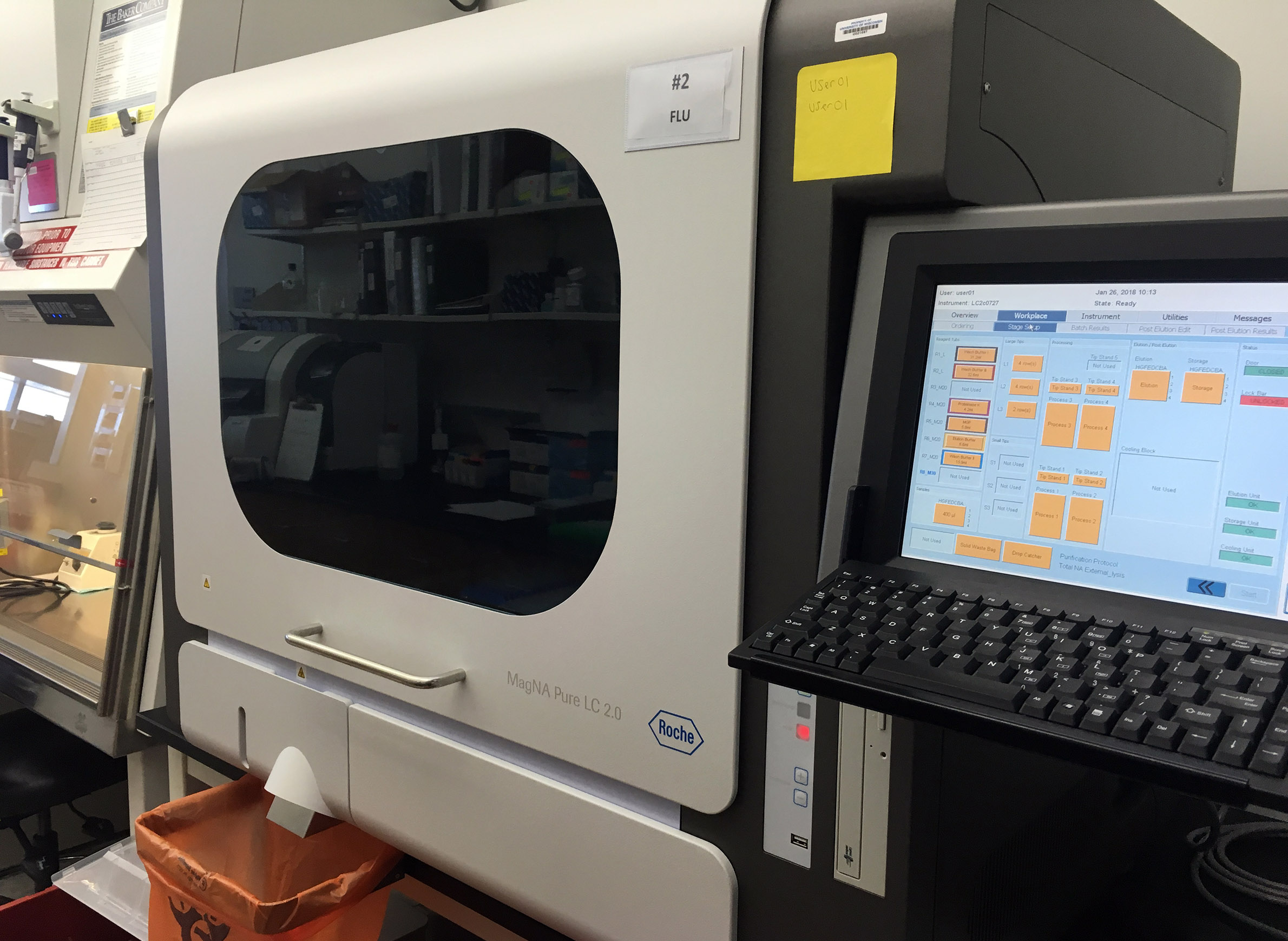

When people like Shult worry about federal funding, they’re not thinking so much about the purchase of one particular piece of equipment as about long-term sustainability and adaptability. A machine like the MagNA Pure LC 2.0, used to analyze DNA and RNA, has regular and highly specialized maintenance needs. It also needs staff who know how to operate it. In turn, this tool generates data that must be organized and analyzed before dissemination to other public and private health institutions.

The initial price tag of such equipment doesn’t reflect the long-term cost of getting meaningful use from it. But beyond any one machine, having access to such technology helps the state hygiene lab do more testing, work more quickly, and adjust when a spike in flu cases prompts an influx of specimens to be tested.

So far the state hygiene lab has kept itself on solid financial footing, but it’s always tough to sell elected officials on the value of laboratory research.

“We’re on soft money,” Shult said. “Public health should never be on soft money. We should be guaranteed. That should go across party lines and everything. Unfortunately, it doesn’t always.”

…has joined the call

The Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene also sends the state-level data it compiles to the state Department of Health Services, which doesn’t do any lab testing of its own on influenza samples, but issues weekly updates during flu season. DHS influenza surveillance coordinator Tom Haupt combines the state hygiene lab’s findings with data from local healthcare providers about influenza-related hospitalizations and outpatient visits. He credits an unlikely secret weapon for flu surveillance: phone calls.

Every month during flu season, public-health officials from all 50 states participate in a conference call to compare notes on what they’re experiencing, identify larger trends in respiratory illness, and trade advice and strategies. Officials from about 10 Midwestern states also hold a different monthly call that shares the same purpose but is a little more informal because the participants have known each other longer and work a bit more closely together, Haupt said. One key thing that’s helpful on these calls is being able to figure out whether something aberrant in a given flu season is an isolated issue or part of a larger trend.

“One of the unusual things that have happened over the past few years is the emergence of people who have mumps-type systems but that have actually got the flu,” Haupt said. “That’s something we notice quite a bit in the Midwest, and we’re seeing that again this year.”

That said, even referring to something in flu season as “unusual” is a bit tricky, because no two flu seasons are alike. Since conditions change every year, communication is all the more important for everyone from CDC scientists to local doctors, as they get their bearings to deal with each season’s distinct mix of influenza viruses.

Haupt and his counterparts in other states also tell each other when they’re having trouble acquiring medications like Tamiflu, or important testing equipment. Through these calls, state public health officials can develop a working picture of what the ever-changing influenza picture is looking like in a given year.

“The last few years we didn’t see cases until like January except for sporadic cases, and these started back in October,” Haupt said at the beginning of February.

“As close as we are to peak activity, we still have not peaked … the number of hospitalizations, it’s not going down at all, it’s continuing to increase. We’re getting over 100 a day [in Wisconsin], we’re up to over 3,600 for the season.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us