When UW Arboretum Restoration Research Fired Up An Oscar-Winning Disney Doc

In the early 1950s, the Walt Disney Company moved beyond animated cartoons to nature films. It was at that point Madison became part of nature film history.

January 8, 2019

Metal sculpture in Curtis Prairie at UW Arboretum

Conservationist Aldo Leopold, the author of A Sand County Almanac, and his colleagues at the University of Wisconsin-Madison were the pioneers of what today is called restoration ecology. The best-known restoration project at the UW Arboretum, Curtis Prairie, played a role in an Oscar-winning Disney documentary.

In the early 1950s, the Walt Disney Company moved beyond animated cartoons to nature films. When creating movies like Bambi, Disney brought in live animals for its artists to study and even had natural science lectures to educate the animators. Walt Disney himself developed an interest in conservation and launched a series of 13 documentaries titled “True-Life Adventures.”

The series focused primarily on the fading frontier, conservation and nature. These films were some of the first of their kind, and served as inspiration for many entries to the genre.

Environmental awareness, at least relative to cinema, can also be traced back to the “True-Life Adventures” series. The first film in the series was Seal Island (1948), set in the Alaskan frontier. Russia and Japan had just signed a treaty on seal hunting and that is likely what caught Disney’s attention.

Seal Island ran for 27 minutes; too short for a feature and too long for a short. Theaters weren’t interested, but Disney managed to get it into a friend’s theater, qualifying it for Academy Award consideration. It won an Oscar for best documentary short subject, and so the series was off and running.

It was at that point Madison became part of nature film history.

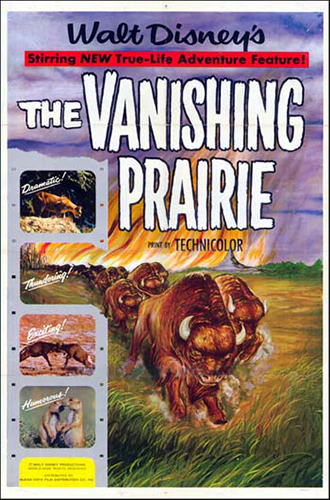

One of the most acclaimed entries in the series was The Vanishing Prairie, released in 1954. Disney needed a prairie for filming, one that reflected a prairie “before civilization left its mark upon the land.” The Curtis Prairie fit the bill and was used for much of the documentary, in particular the scenes of a prairie fire, which was filmed during a controlled burn.

John Curtis and Max Partch conducted groundbreaking research on ecological restoration at the UW Arboretum in the 1940s, documenting the important role of fire in maintaining and restoring prairie landscapes.

Prairie fires still occur on the Curtis Prairie and elsewhere at the UW Arboretum during spring (March through May) and fall (November-December) prescribed burning seasons. Fire is a part of the ecological process that shapes Wisconsin’s plant communities. It is a natural phenomenon that helped maintain various ecosystems, including the prairie, before European settlers arrived.

Prescribed fire is deliberately set under expert supervision to achieve ecological objectives to maintain or re-establish plant and animal communities. Factors like weather (temperature, wind speed and direction, and humidity), fuel load, and smoke management are part of the burn plan to reduce risk.

Over the last 25–30 years, approximately 100 acres of UW Arboretum lands were treated with prescribed fire every year. Currently there are around 20 areas (including outlying properties) that are managed with regular prescribed fire by prescribed burning professionals.

Only portions of The Vanishing Prairie were filmed in Madison. It is unlikely footage of prairie dogs or a bison giving birth was filmed in Madison; the New York State Censorship Board banned the film due to that latter scene (but later relented).

The Vanishing Prairie won an Oscar for best documentary feature in 1954. Disney’s clandestine nod to a conservation ethos can be seen in the film’s title changes, from The Grazing Story to The Prairie Story to finally The Vanishing Prairie. Walt Disney’s goal was that “the vanishing pageant of the past may become the enduring pageant of the future.”

The series was shown in public schools for decades and influenced many young people to choose careers in conservation and forestry.

Since the UW Arboretum publishes its prescribed fire schedule online prior to each burning season, with a little planning, it is possible to see a real fire on the “vanishing prairie.”

Thomas Straka is a professor in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Conservation at Clemson University. He studied forestry at UW-Madison, and spent many hours in the UW Arboretum. This article was originally published on Oct. 25, 2018 in Isthmus.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us