Opium, Opioids And A Pendulum Of Pain

The story of opioids in the 21st century is one fraught with urgency, pain and heartbreak.

February 21, 2019

Opium poppy pod with OC stamp illustration

The story of opioids in the 21st century is one fraught with urgency, pain and heartbreak. But this type of pain-relieving drug wasn’t always riddled with stigma. Rather, they are but the latest issue in a centuries-long relationship people have had with opium, opiates and their effects on those who use these substances.

To understand how opioids came by their contemporary and often-negative reputation, it’s crucial to examine their history. June Dahl, professor emerita of neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health, discussed the history and changing perceptions of opium and its pharmacological descendants on March 28, 2018, at a Wednesday Nite @ the Lab presentation on the UW-Madison campus recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

Dahl framed the history of these drugs through the complicated relationship doctors have with pain and, as a result, pain relievers like opium, simple opiates and what are now called opioids.

The earliest reference to opium use was in about 3500 B.C.E., Dahl said. By 1300 B.C.E., the Egyptians cultivated the opium poppy plant, and its use spread when in 330 B.C.E., Alexander the Great introduced it to Persia and India. In the late 17th century, Thomas Sydenham, who Dahl described as “the father of English medicine,” recognized the power of opium, calling it “one of the most valued medicines in the world.”

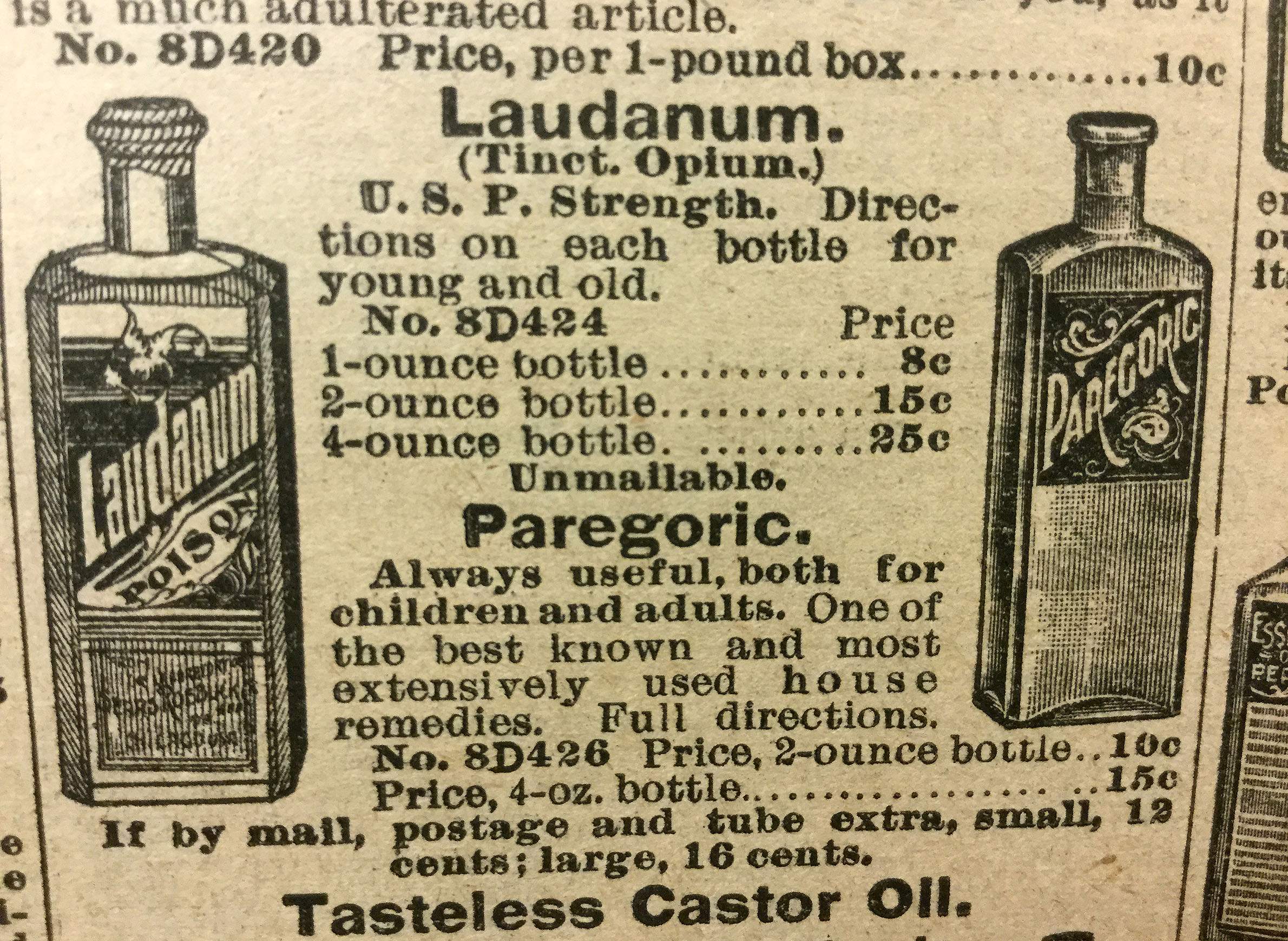

Opiates like laudanum, codeine and morphine became the go-to treatment for many ailments in the US in the 19th century. From treating gastrointestinal illnesses to soothing teething children, these analgesics became a catch-all prescription, most often used for their “calming effects.”

“A drug that calmed people down was very appealing because physicians had almost nothing to work with at that point in time,” Dahl said. “There weren’t effective agents, there wasn’t even aspirin. So that was the good times when there was opium.”

But eventually, the tides changed, or, as Dahl characterized it, “the pendulum swung back.”

By the 20th century, opiates and what increasingly were termed opioids were heavily scrutinized and their use increasingly controlled and prohibited. But the pendulum swung once again by mid-century when the focus of doctors looking to use these types of drugs shifted toward treating people suffering the pains of cancer and other terminal illnesses.

This period of opioid acceptance was short lived, however. In the early 1970s, as states and Congress established strict new drug laws and President Richard Nixon announced a “war on drugs,” an ensuing strain on morphine supplies left people facing chronic pain with fewer resources for treatment.

“The magnitude and scope of pain treatment inadequacy hasn’t decreased substantially in the past decades in the United States, despite the fact that there’s been a long-standing awareness of this problem,” Dahl said.

In 1997, Dahl worked with the Joint Commission, a non-profit organization that grants accreditation to health care organizations, to develop standards of pain. The idea behind this effort was to compel doctors to confront their patients’ issues with pain, despite fears of the adverse effects of opioids and the general stigma against the analgesic. Dahl noted that some critics have blamed the subsequent opioid crisis and wave of overdoses on those standards.

Opioid prescriptions rapidly increased in the early 2000s with the embrace of pain relievers like oxycodone and hydrocodone, followed by abuse and an epidemic of overdose deaths. Dahl explained that a big part of the opioid crisis flows s from another crisis of patients not getting adequate pain treatments, along with the rising costs of alternative therapeutic measures.

Dahl said the opioid pendulum remains in motion, slowly moving from prodigal prescriptions of the drugs to a more measured and safer approach. She said a growing concern among medical professionals now is making sure it just doesn’t swing too far, leaving patients to suffer in pain.

“Pain is inevitable, but suffering is optional. And what we’ve got to do is to make suffering much less in this country,” Dahl said. “It’s not optional for us to allow things to continue as they are and they’re only getting worse at the present time.”

Key facts

- Opium is derived from the opium poppy plant (Papaver somniferum). It is harvested from the plant’s seed pods, which are illegal to possess in the United States. Latex in these pods contains morphine, codeine and thebaine. Thebaine is a raw material used to synthesize other opioids, and can be harvested from other poppy species.

- The term “opioid” refers to prescription drugs like oxycodone and hydrocodone, synthetic compounds like fentanyl, long-used drugs like codeine and morphine (that have also been called opiates), as well as proscribed substances like heroin.

- Opioid-based medications can be used to relieve pain, induce sedation, suppress a cough and more. Many prescription pain relievers include multiple analgesics in addition to opioids. Vicodin, for example, is a mix of the opioid hydrocodone and acetaminophen.

- Opiates were widely prescribed by doctors in the 19th century. They were used for everything from calming teething babies to treating “hysterical housewives.” Morphine salts were introduced in 1832, contributing to a dramatic increase of morphine consumption, which peaked in 1896. In the 20th century, perceptions of opioids changed dramatically. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, approved in 1914, aimed to regulate opiates and tax their production, importation and distribution. This legal crackdown against opioids and other drugs reached a new level in 1956 when the federal Narcotics Control Act made the sale of heroin to minors punishable by death.

- When it comes to defining what is called the “opioid crisis,” there are many factors at play. There is the health crisis surrounding overdoses and accompanying deaths, which has come to the forefront of national attention in the 2010s — the federal government declared a national public health emergency over the opioid crisis in October 2017. An emerging opioid-related crisis is an increase in unrelieved pain, as concerns about opioid abuse have led to decreases in prescriptions.

- The types of opioids being abused is varied. The majority of overdose deaths in recent years have been related to fentanyl or a combination of opioids with other drugs such as alcohol. Patients receiving pain management treatment based on opioids and follow their prescriptions are not abusing the drugs or experiencing overdoses.

- A newly presented problem related to opioid overdoses is the propensity of people to take them with benzodiazepines, which has proven to be an extremely lethal combination.

- Controlling the pain cancer patients through the use of opioids has been contentious. In 1984, Congress considered a bill that would make heroin available to treat the pain of the terminally ill. While the bill failed to pass, it shed light on the issue of pain treatment that accompanies terminal illness. Researchers have found in recent years that the magnitude and scope of pain treatment inadequacy hasn’t seen a substantial decrease in the past decades.

Key quotes

- On the effectiveness of opioids: “I always tell the students that every patient is an individual pharmacologic experiment. So you can’t just read a textbook or a manuscript and figure out how long it lasts. You have to ask the person. So some people get six hours of pain relief from morphine. But most get three to four and some may even get two.”

- On the origins of opium: “The earliest reference to opium growth and use was in about 3400 B.C.E. … By 1300 B.C.E., the Egyptians were cultivating opium and they named it on the basis of the capital of Egypt at the present that time, which was Thebes. Hippocrates who is considered to be the father of medicine, noted way back when the pain-killing properties of opium. And around 330 B.C.E., Alexander the Great introduced opium to Persia and India.”

- On the freewheeling use of opium and its constituent drugs like morphine and codeine in the 1800s: “Before 1800, crude opium was widely available in the United States and it was an ingredient in multi-drug preparations. And, of course as I’ve already told you, in laudanum which was 10 percent opium in alcohol. And it was very valued for its calming and soporific effects. It was also a specific treatment for GI illnesses. Given that opioids cause constipation, it’s an interesting balance to think about treating GI illnesses.”

- On the medical practice of using opioids for pain management: “The limited therapeutic alternatives for this horrendous problem have combined to produce an overreliance on opioid meds. And this, associated with this alarming increase in diversion and overdose and addiction, that physicians understandably have questions about whether and when how to prescribe opioid analgesics for chronic pain.”

- On the effects of benzodiazepines mixed with opioids: “Deaths involving benzodiazepines increased from 1,135 in 1999 to 8,971 in 2015. … three-quarters of deaths involving benzodiazepines … involved an opioid of lethal combination. I think it’s important also to accept the challenge presented by the National Academy of Medicine. We need a cultural transformation to better prevent, assess, treat and understand pain of all types. The level of ignorance is really profound. It always astonishes me.”

- On moving forward in pain treatment: “We need to maintain our focus on pain. Its undertreatment is a major public health problem in the United States. Certainly the number of persons who have chronic or persistent pain is just mind-boggling to me. We need to maintain a balance. We need to assure that efforts to reduce the diversion and abuse of opioids don’t interfere with their appropriate medical use. I think that is not the case at the present time. I think there’s a lot of interference with appropriate medical use.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us