Where Wisconsin's Summers Are Heating Up Most

Complaints about living in the Midwest often hinge on its seasonal extremes as a top reason to steer clear of the region, and a July 2019 study highlights the health risks posed by dangerously high summer heat in Wisconsin and throughout the United States.

By Will Cushman

August 5, 2019

Sunset over Sunset Beach Park at Fish Creek in Door County

Complaints about living in the Midwest often hinge on its seasonal extremes as a top reason to steer clear of the region. Though winter often receives the brunt of this meteorological hate, summer heat in many parts of the Midwest, Wisconsin included, can soar to heights that are unbearable and even, at times, deadly.

A July 2019 study highlights the health risks posed by dangerously high summer heat in Wisconsin and throughout the United States. Produced by the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit science advocacy organization that focuses on climate change as one of its priorities, the study underscores the growing risk of climate-linked heat waves in North America. This research compares the average number of days each U.S. county has historically experienced dangerous heat thresholds with what those communities may expect under varying climate-change scenarios. It landed, coincidentally, during the hottest stretch experienced in Wisconsin since 2012.

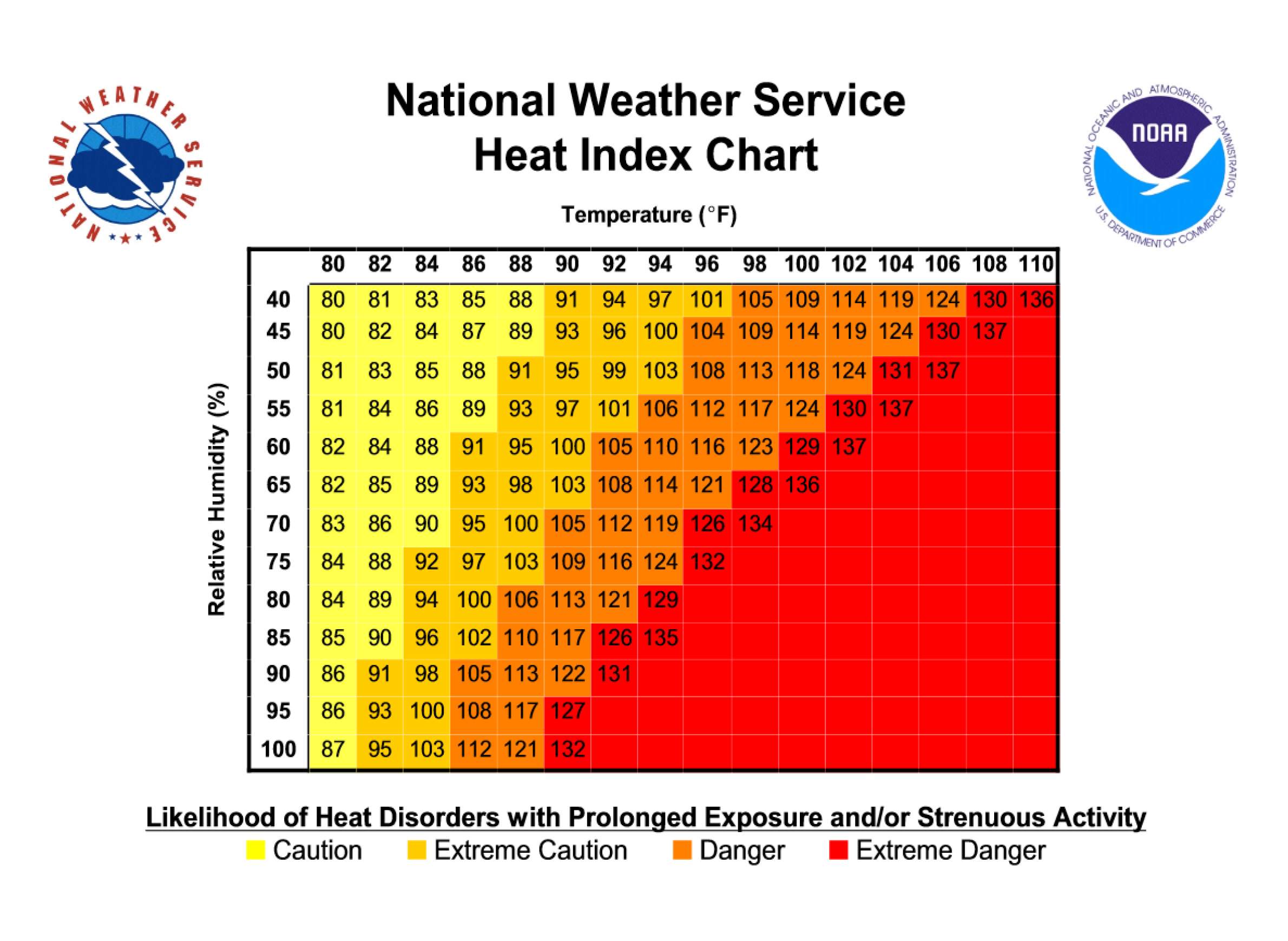

In its report, the Union of Concerned Scientists zeroed in on the heat index, a weather indicator based on two variables — temperature and relative humidity — that control how hot it feels outside and, therefore, have important implications for public health. The heat index is particularly relevant in the Midwest, where, unlike hot and arid regions, such as the American Southwest, relative humidity is often high enough to make hot temperatures feel even hotter by frustrating the human body’s mechanisms for staying cool.

This indicator is significant in Wisconsin because dangerous heat in the state is not commonly the result of air temperature alone; instead, relative humidity often makes more typical hot temperatures feel dangerously hot. For instance, an air temperature of 85 °F can feel closer to 90-95 °F under relative humidities that are fairly common during a Wisconsin summer. When the air temperature itself becomes dangerously hot, relative humidity only exacerbates heat-related health risks, especially for vulnerable populations like the elderly and young children.

That relationship between temperature and humidity underscores the study’s sobering forecast of what Wisconsin residents can expect in decades to come: namely, more frequent and more dangerous heat waves, even in regions where people are currently unaccustomed to them.

Where are these historically heat-free havens in Wisconsin, and what do climate models forecast for their future?

Many Wisconsinites have the Great Lakes to thank for putting a lid on summer heat. From Manitowoc north to Washington Island, communities along the Lake Michigan shoreline rarely experience heat that feels 100 °F or hotter. The same goes for Lake Superior shoreline communities, and to a lesser extent, the inland North Woods.

Historically, the Door Peninsula, surrounded on three sides by temperate waters, is Wisconsin’s coolest summertime locale. Partly for that reason, Door County is a popular respite from steamy weather elsewhere in the Midwest (and beyond). Indeed, the county is the only one of Wisconsin’s 72 counties where 100 °F heat is nearly unheard of, or at least was unheard of.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s North America Land Data Assimilation System, which maintains heat index records from 1979-2011, residents in Door County experienced only one day with a heat index above 100 °F during that 33-year period. The blip occurred in the midst of a brutal heat wave that baked the Midwest in July 1995. Dozens in Milwaukee died from heat-related causes during that heat wave, which also killed hundreds in Chicago.

In contrast, the July 2019 heat wave produced heat indices in Door County topping out around 94 °F.

The CDC’s heat index records reflect a period about 10 years later than the historical climate records analyzed by the Union of Concerned Scientists in its 2019 study. Those latter data were gathered by scientists at the University of Idaho and reflect a period from 1970-2000. A comparison between the two datasets shows that the average number of dangerously hot days looks to already be increasing in many Wisconsin counties, particularly in the southwestern portion of the state.

Crawford, Grant and Lafayette counties, in the state’s southwest corner, saw some of the largest increases in the average number of days each year with dangerous heat between the two time periods, from around 3 days per year with heat indices above 100 °F during 1970-2000 to more than 7 days per year during 1979-2011. Distant from the moderating effects of the Great Lakes, these counties, and much of western Wisconsin in general, have historically experienced more dangerous heat than those farther north and east. Still, most counties in Wisconsin saw an increase in the occurrence of dangerous heat between the two periods.

According to Michael Notaro, associate director and senior scientist at the Nelson Institute Center for Climatic Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, higher recorded heat indices in Wisconsin and the Midwest are thought to be associated more with higher relative humidities than with higher air temperatures.

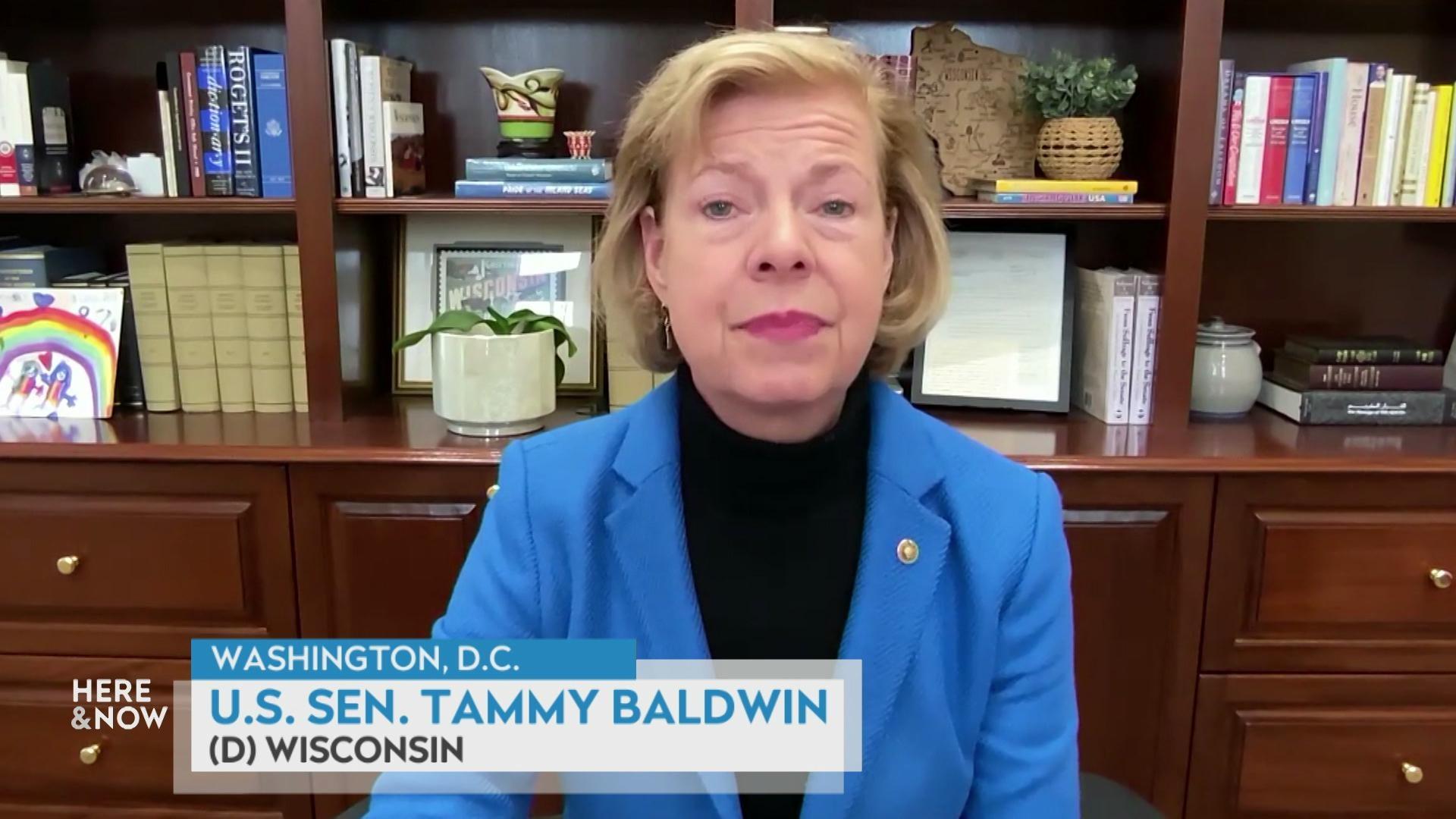

“[W]e have in the Midwest what’s known as a warming hole, where the summer high temperatures have not yet warmed, but we’ve actually observed the dew point temperatures and heat indices have been increasing,” Notaro said in a July 19, 2019 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now.

Notaro was referring to 2018 study produced by atmospheric scientists at the University of California-Davis that connected the increasing frequency of dangerous heat in the Midwest and elsewhere with higher moisture content in the atmosphere.

Meanwhile, the longer-term outlook for Wisconsin is considerably hotter, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, even under climate scenarios where global greenhouse gas emissions are significantly curbed.

Under the worst-case scenario offered by its study, which incorporated 18 widely accepted climate models, even summertime havens like Door County could become significantly less hospitable by the end of the 21st century.

In the scenario in which no globally significant action is taken to curb greenhouse gas emissions, Door County is projected to experience more than two weeks of heat indices above 100 °F each year by the end of the century. That number is more than double the occurrence of dangerous heat experienced in state’s hottest counties between 1979-2011. The outlook for residents in those regions, which include densely populated parts of Milwaukee and its suburbs, along with Dane and La Crosse counties, is downright bleak, with more than 40 days of heat indices at or above 100 °F forecast every year.

The projected heat indices could be especially risky for Wisconsin’s farmers and other outdoor laborers, and threaten to burden dairy farms in particular, as milk production requires cool conditions.

Still, there is room to interpret the study in a not-so-gloomy way, according to Rachel Licker, a senior climate scientist with the organization. That’s because the report also makes forecasts that assume varying levels of global action to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

“One could look at this study and be very discouraged, but I actually look at it and see it as a sign of hope that if we do take action there are a lot of dangerous outcomes we could avoid,” Licker said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us