Racial Identity and Belonging

“I still feel like, in a way, being a Latino, I’m not always accepted.”—Johnathan Delgado

Racial Identity and Belonging

Racial identity is simultaneously personal and shaped by society, culture and history. Angela Fitzgerald speaks with Johnathan Delgado about navigating identity in a world where who you are may be questioned or denied. They explore how stereotypes, rejection, and isolation impact mental health, and what it means to find strength in identity despite exclusion.

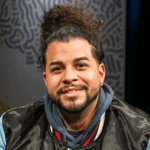

GUEST

Johnathan Delgado

Johnathan Delgado, based in Madison, Wisconsin, is a dedicated grassroots community engagement specialist and the founder of the Puerto Rican Awareness Project — a coalition committed to promoting Puerto Rican culture and addressing community issues.

TRANSCRIPT

[bright music]

Announcer: The following program is a PBS Wisconsin original production.

Racial identification is both personal and shaped by society, reflecting how people see themselves and how others perceive them. It’s tied to culture, history, and lived experiences, while also being influenced by societal systems that often reinforce inequality. For some, it’s a source of pride and community. For others, it brings challenges like stereotypes or discrimination. But what happens when the identity you claim is rejected by those around you? How does this sense of isolation impact your mindset? Let’s explore why race matters when it comes to racial identification.

The concept of race has evolved over time, often shaped by societal and political forces. Initially, race referred to groups connected by kinship or shared traits. However, during the 17th century, European thinkers began categorizing people based on physical characteristics, leading to the modern notion of race. These classifications were frequently used to justify unequal treatment and discrimination. For instance, in the United States, racial identification has been a basis for systemic inequalities, affecting various aspects of life.

Today, individuals navigate complex racial identities, often facing challenges related to discrimination, belonging, and societal expectations. The journey toward embracing one’s racial identity can be fraught with difficulties, but it also offers opportunities for personal growth and community connection.

On this episode of Why Race Matters, we’ll talk with Johnathan Delgado about navigating identity and community.

Thank you for joining us tonight, Johnathan.

Johnathan Delgado: Yeah, thank you for having me.

Angela: So I feel like tonight’s conversation is unique when compared to some of the other conversations we’ve been having on Why Race Matters, simply because you are presenting a case study opportunity for us to talk about race within our state in a way that we might not always have conversations around, because of your background and your story. So I’m hoping we can have more conversations like this, but I appreciate you being the first.

Johnathan: Yeah, absolutely. You know, any way to help or at least help understand, you know, actually how diverse our state is.

Angela: Absolutely, and so to kick us off, we want to acknowledge that you are a Puerto Rican individual living in the state of Wisconsin, living in the city of Madison. You’re from Chicago. But in terms of your place of origin, you’re from Puerto Rico.

Johnathan: Yeah, I’m a transplant really. If we’re gonna be completely honest, I’m a transplant. Yeah, so born and raised in Chicago. I was there ’til about 12 years old, but I’ve been a resident of Madison, Wisconsin, for about 21 years now.

Angela: Oh, wow. So it feels like you’re a Madisonian at this point, I would say.

Johnathan: Yes, Madison’s home, but it’s not where I’m from.

Angela: So can you tell us about where you’re from, both contexts of where you’re from, and especially, I would say, highlighting your original place of origin, Puerto Rico, because for many of us in Wisconsin, there may not be a full context of what we should know about Puerto Rico from your perspective. So anything you can share that then helps to bring us to the present and your experiences here. Definitely appreciate it.

Johnathan: Yeah, so I’ve been here 20 years now. And I think exploring, you know, what it means to be an Afro-Puerto Rican person in our community is different than how we would go about, like, maybe in Chicago, right?

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: Historically speaking, you know, Puerto Rican people have been in Wisconsin for the last 100 years, right, at least. We came here in the early 1920s to support agricultural production of crops and other things. And, you know, I personally, though, grew up in inner city Chicago, so it’s a little different. And moving here was a little bit of a culture shock. It was different. And, you know, in terms of being Puerto Rican in this community, I really didn’t start meeting Puerto Ricans here in the state or in Madison until I moved to the east side of Madison. You know, the first day of 8th grade, I’m in the lunchroom, and a couple of—who are still friends today—walked up to me and they said, in Spanish, “Tu eres Boricua?” And which means, “Are you Puerto Rican?” in Spanish. And I just walked away. And so it was a really interesting, just, like, experience for someone.

Angela: Wait, why’d you walk away?

Johnathan: They walked away.

Angela: Oh, they walked away.

Johnathan: Yeah, they walked away. And I’m not, you know… And I think it was just kind of like, they were confirming whether or not, like, what I looked like, right? I think they were like, “Oh,” like, “Hey, we, we think we see another Puerto Rican. Let’s go see if it is.”

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: And that’s essentially what happened. And so we’ve been friends since. And we do our best to try to, like, link up with the Puerto Rican community here, but I think it’s hard ’cause our history is kind of lost to a lot of America, and not a lot of people understand what it means to be our subsection of Latino. Right, it’s different.

Angela: Can you break that down for us? Because you’re right, I think a lot of us A, have never been to Puerto Rico, especially, I’m thinking about the distance between Wisconsin and Puerto Rico, even how to refer to Puerto Rico as a state, territory, island, like, not necessarily always knowing the correct terminology or what that means for people who live within Puerto Rico, what their experience is like compared to maybe being a resident within the state of Wisconsin. So can you just give us a little more context about Puerto Rico, things that you would like people to know and understand.

Johnathan: It’s really old. And I think, like, as an island, the island of Puerto Rico, or Borinquen, has been an occupied or a lived-in space for over 25,000 years, so… And that goes back to our ancestors, the Taínos, which I think is kind of a general term used. We really don’t know if that’s what the people called themselves, right? That’s just kind of what we have an idea of now. But we’ve been on the island for a really long time, up until 1498, when Christopher Columbus and his three ships sailed the blue, the mighty blue, and landed in Santo Domingo, which is in Quisqueya, or Dominican Republic. And in, within his voyages, you know, in my opinion, Puerto Rico has been a colony for over 526 years. And to this day, the relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico are one that confound to terminology, in a way, to lessen the impact or the viewable impacts, in my opinion. If I’m gonna be honest, Puerto Rico is a colony of the United States. It’s just different issues that we see on the island. We don’t have the ability, or my grandparents, my brother, or my family who are there, they are not able to vote for our president, and they pay American taxes. And so to me, why I call it a colony is because we have a modern day example of taxation without representation. And so those are my views.

I also grew up in a family in Chicago. My family have been in Chicago for a little over 70 years, maybe longer. It goes back, my great, or my grand, my great-grandparents came here, and then my grandfather, he started one of Chicago’s first Latino gangs. And back in the day, they didn’t view themselves as a gang. They were actually a dance social, if we’re gonna be completely honest. They came together and were dancing. That’s what it was about.

Angela: So thinking like Michael Jackson’s Beat It video, like, that type of gang?

Johnathan: I’m gonna say like Tito Puente and his, like, 18-piece band, right? We’re talking, like, you know, live performances within the community of people who knew how to play different instruments would come together and play salsa. Right?

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: You know, and Chicago’s an interesting place ’cause we, you know, here in Wisconsin, we talk about Milwaukee being one of the most segregated places in America. If we go over to Chicago, it’s, they resemble each other in a lot of ways, right? But I think in Chicago, there’s a little bit more cohesivity between them.

Angela: And to that point, you initially introduced yourself as an Afro-Puerto Rican and as a member of the Latinx community. So can you just tell us more about how you identify, and then in navigating your multiple identities, what that has been like for you in Wisconsin. I know you’re from Chicago, and Chicago has more diversity than Wisconsin. So what that’s been like for you moving to a state that has less diversity.

Johnathan: I think being here made me double down, right, in my culture, in who I am as a person. And really, you have to try harder here, in a way, to be a part of the community, right, in a way, and…

Angela: Well, ’cause you may have to help create space for that community, or cultivate that, because it may not be just apparent and there for you to connect with.

Johnathan: Yeah, so I said Afro-Boricua. And what that means is I am of African and Indigenous Puerto Rican, or Boricua, which is another word for Puerto Ricans that was given to us by the Indigenous people. So our island itself was called Borinquen. And so we use Boricuas as a way of identifying to the specific island of Puerto Rico. And when I say Afro, I say Afro because I am also Afro, like, I am a part of a community that comes in many different shapes, sizes, and colors. And my mother, she’s a Black Puerto Rican from the town of Trujillo Alto, which is historically known as a, it was a settlement community of freed slaves on the island of Puerto Rico. Which Puerto Rico itself, it’s called “rich port,” right? ‘Cause you can get anything on the island. And unfortunately, our island has a history with, entangled in the slave trade.

You know, our island was, you know, we were, unfortunately, a port for chattel slavery and likely have done business with the United States and other regions of the world. And you know, I think it’s interesting and it’s sometimes hard to conceptualize of, you know, like, how long ago this goes back. But my family in Trujillo Alto have been there for 130 years now. And so, you know, my great-grandfather, born 1886 or something crazy, lived to be 117, was the child of a freed slave person. And so, you know, and I think that when we think about, you know, where we come from, it’s important to, like, hold on to that, or at least that knowledge, right? And to, you know, acknowledge that, hey, my family have been in one spot. And that’s not something that a lot of my Black and Brown brothers and sisters have here. You know, we don’t have a tie to a specific spot. And I think that also, you know, disenfranchises us, right? And so it creates additional challenges.

Angela: Absolutely, because even your very core identity is lost when you can’t track back to where you came from, which then lends to the creation of a new identity, a merger of old plus new. And then there’s a cultural impact you can have with that. But I think there’s still a longing for wanting to know more about where you’re from and who you are. So I think that’s amazing that you have that connection to know about your past and your lineage, to be able to inform present-day you.

Johnathan: Yeah, it took a really long time for that. And I, you know, I think living in Wisconsin, I turned away from anything being Puerto Rican. I didn’t speak Spanish. I had to reteach myself Spanish, just to avoid the questions. And, you know, I think it was about 21 when I was—I’m a young parent. I was a young parent. And so when I turned 21, I had a child. And right around that same time, I was having kind of, like, a crisis of, like, you know, how can I be a parent if, you know, maybe I didn’t have the greatest examples of a parent or, you know, maybe, you know, how can I do it if I don’t have the support, you know? And so I think I went through this stage of learning my own history, in turn, offering me an insight to a broader and more larger history. And I think for me, that is, you know, having my son, my kid, right, like, was a huge turning point for me. And, you know, now I had to question everything, you know, like what happened? Like, there’s so many little things that I had, traumas that I had compartmentalized and put away in the back of my head. Right, you know, like, I wasn’t raised by my mother. I was raised by my father’s mother. You know, and having to learn about my mother through other people, especially young, was, it wasn’t negative, it was negative, right? So I stopped asking questions.

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: And so learning about our community, or learning about me really just ultimately helped me understand that as a Puerto Rican person, I’m not the only person or the only Puerto Rican, the only African American, the only Black person, I’m not the only person going through the things that I’m going through, and that has historical context. Right, and so…

Angela: Absolutely. Because even you saying that you had to reteach yourself Spanish because you were trying to avoid certain questions, right? That sounds similar to, when thinking about assimilation into a culture that’s not your own. Unfortunately, for a lot of us, that means shedding certain things that might other us to try to become like what we feel the dominant culture is, which does come at a cost. Not just to us, but to the larger culture, which doesn’t benefit from what we have to offer. So in going back to that experience, like, what sorts of questions, or what things were you contending with that, for that period of time, meant that you weren’t fully showing up as the Johnathan that you are? You felt like you couldn’t show up as the Johnathan that you are.

Johnathan: Yeah, when I first moved here, I moved here, and my father lost us to the system, and we ended up, me and my two siblings ended up moving in with my aunt and her five kids.

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: And that experience was different because, you know, you have my aunt who is a white woman and Puerto Rican, right? Their, you know, her relationship to being Puerto Rican was skewed, in a way, ’cause she didn’t grow up in the culture. She didn’t grow up in the, you know, in what it means, right? She just, you know… You know, in my opinion, she was very much representative of the Caucasian community. Like, in my opinion, you might not be able to tell just with her fair skin. Like, she had, you know, fuller features, maybe, darker complexion, slightly darker complexion, but, like, definitely passing. And her children as well. And I think living with them, there was always the questions of, like, “Why do you live with your aunt? Why do you,” you know, like, there is, there was always some type of question of, like, “Oh, what are you?” or, “What is…?” I don’t know, it was just always a question about, you know, where it is that I come from. And I just wanted to shut it down. I just didn’t wanna have that conversation. Like, I know where I’m from. I’m from the inner city Chicago. Paseo Boricua. Like, you know, my community, that’s where I was from, you know. But even when I would say “from Chicago,” it was never good enough. It was never, you know what I mean? It was like, what, “But really, where are you from?” Or Mexican, I’d get a lot of, “Are you Mexican?” And I love my Mexican brothers and sisters. And I understand that, you know, when it comes to Latinos, Latinas, and Latinx people, there’s 28 different Spanish-speaking countries and people who live in our states, right? And when the largest subgroup is Mexican, obviously, you know, there’s—

Angela: People assume.

Johnathan: People can assume. People make the assumptions. And, you know, when I was younger, I used to, you know, really hate that. I used to hate being called Mexican, or hated this or that, when really I just didn’t understand. Most people just don’t know. They don’t know how to ask the question properly, right?

Angela: Right.

Johnathan: You know, when it comes to, you know, learning about other people, it’s great to ask questions.

Angela: Absolutely.

Johnathan: Ask questions, however—

Angela: But there’s a way to ask the question.

Johnathan: Yes, yes, yeah. So, like, I’m not against that. But it took me a long time to realize that, you know, like, it was not ever that I don’t like the Mexican community. And I think that’s the question I’ve got. “Oh, what’s the beef between you and the Mexican community?”

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: Or like, not you, but, like, Puerto Ricans…

Angela: Puerto Ricans.

Johnathan: …and Mexicans. And, you know, I personally have no beef with any Mexican person or any person of a Latino or Latinx community. I’m not, I don’t have any beef. I do think, though, because of our socializations and our, where we might come from in the community, right, if you’re just not a part of the community, you know, you’re just, you just don’t know, right? And so I think it’s always been like, no, now I have an appreciation and I can understand why.

Angela: Well, and I think what you’re sharing, I’ve heard similar sentiments from other people from South America, other Spanish speech, Spanish-speaking countries who, if you come to a setting where, A, there’s not a ton of diversity, so exposure to difference within certain cultures is limited and the largest subgroup is Mexican, people make that assumption. Like, “No, I’m Colombian.” “No, I’m Bolivian,” “No, I’m from Nicaragua.” Like, there’s loads of other places I could be from. Just because I speak Spanish doesn’t mean by default I’m Mexican, which is honestly, like, a national conversation as well, because I think nationally, there’s the assumption that any person who’s Brown or speaks Spanish is Mexican, when that’s just not the case. So I think there’s an opportunity for all of us to learn more about difference, and especially if we are attempting to move the needle to arrive at a place where we feel like our state is more equitable. And part of that is just understanding the people that we would be supporting, in terms of that effort.

Johnathan: Yeah, absolutely.

Angela: I think it’s funny when you said, well, “I stopped speaking Spanish as a way to almost, like, avoid the questions.” But I’m like, in looking at you, like, you’re still gonna elicit questions even without opening your mouth. So you not speaking Spanish, I don’t know if that quite achieved your goal, but I understand, I understand. And so, I guess, in building off of what you just said in helping people understand, like, difference within the Latinx community, what has that experience been like for you navigating, connecting, and being part of the Latinx community while also maybe being a smaller subset of representation within that community, at least within the state of Wisconsin?

Johnathan: Yeah, I, that’s a great question because, you know, when it comes to the acceptance or, you know, garnering the acceptance of your fellow, like, Latina, Latino, Latina, Latinx. And I always try to, like, say, all of them because I want to acknowledge that not all people necessarily identify with Latinx, but, like, I want to include, I, personally, I’m a Latino, you know, and I think that the difference between just, like, simple terms, right, it dilutes difference. It itself is the thing that makes it hard, right? I think understanding, you know, race, right, understanding race allows us to understand our own biases.

Angela: Mm, mm-hmm.

Johnathan: Right? To be able to say, “Oh, well, you know, I thought this one way, and something happened, and now it’s another way.” That’s a good thing, generally speaking, right? Like, it’s a good thing to have an idea and to change it if it means it’s for the better. But to be completely honest, as a person who kind of, like, renounced being a Latino for a majority of my, you know, teens and, you know, part of my developmental ages, right, like, I think that I turned away from the language because, and the culture in a way, too, right? I had to turn away from it ’cause I was dealing with life in Wisconsin, right? And so in a bit of a survival mode. So how can I, you know, be able to, like, really enjoy and express and do all of those things when everything else in life felt so chaotic? And I think, you know, garnering that acceptance by other Latinos, it doesn’t happen. Like, it didn’t happen, right? ‘Cause one, I wasn’t speaking Spanish and I was also avoiding people who spoke Spanish.

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: And, you know, nowadays, now in my adult years, I still feel like, in a way, being a Latino, I’m not always accepted, you know, or because I’m Puerto Rican and I have papers or I’m a citizen, you know, there’s this idea that I think that I am better than other, you know, Latinos or Latino immigrants.

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: And I think that is kind of like a negative stereotype that Puerto Ricans have, is that because of our, you know, our status as Americans, it creates additional divides between us, right? And the same goes to say with even being a part of the Black community, right? Like, I grew up in the inner city of Chicago. You go two big street lights down the road, you’re in the south side of Chicago. It was predominantly Black and Puerto Rican, you know. So a lot of times if I say, even if I say I’m Puerto Rican, a brother and a sister, they’re gonna be like, “Hey, hey,” you know? Like, they’re gonna be excited. They see me as a part of their community. They see me in a different way that I’ve never really gotten. I mostly only get love from the Black and Brown community or Black community, right? African Americans, I get mostly love. I’ve had a handful of times where an African American Black person would be like, “You ain’t Black, you ain’t…” you know? And so, it’s, and it’s not about whether I am or I’m not. It’s just, you know, culturally speaking, where I come from, what I know, the language, the, you know, to being able to code-switch in certain areas, you know, that there’s, that comes from somewhere, right? And my connection to my Blackness is through my mother, is through her family and beyond, right? And so I think, you know, learning to accept, like, those parts, right? Learning to accept all these, like, little things that I really tried to hide, right, it inevitably just changed me, but also allows me not to care about the discussions or the naysay or the, “You’re not a part of this community.”

Angela: Right, which is so interesting. Thank you for sharing, by the way, just the whole concept of race and ethnicity and how we sometimes merge the two or don’t understand how they differently show up or serve as so much of an influence behind how we navigate our world. Because ethnically, I can’t roll my Rs like you do. But the bora—

Johnathan: Boricua.

Angela: There we go, thank you. I didn’t wanna try. Like, I know I’m gonna mess it up.

Johnathan: It’s okay, it’s okay.

Angela: Boricua, so ethnically, and that ties you to Indigenous Puerto Rico. Racially, which we all know is a social construct. They are the choices that were created to label people and that informed, within that realm, you would check the box that identifies you as Black because of your connection to your African roots.

Johnathan: Right.

Angela: Because even thinking about the categories, there isn’t a Puerto Rico category…

Johnathan: No.

Angela: …when you fill out your census, for example. Like, you have to pick a box, and you mention your aunt who you lived with for a period of time, would have picked a different box than you did. So I think that’s the nuance when we talk about identity and then where people feel like they find community or acceptance. So a lot of times, informed by things that none of us created, but we’re just forced to navigate them. And that can be trickier when you’re in spaces where there’s even less diversity and less understanding about the hoops you might have to jump through to even just establish a sense of who you are within a particular space. ‘Cause we have similar conversations with people who are from the continent of Africa who are here, and what does it mean to be Black, right? And how does that meaning land differently depending on who you’re talking to, and how that creates different divides, et cetera? Although it’s interesting when you mentioned prior your American privilege, that some folks in the Latino, Latina, Latinx community feel that you have, because prior, you were suggesting, “My American privilege isn’t like other parts of America’s privilege. So I even have a lesser privilege than if I were born in Wisconsin,” for example. So it feels like it’s all sort of relative, like… And again, we didn’t create any of these systems. We didn’t decide these rules. We’re just in them, trying to make the best of what was presented to us.

So I guess in working through those things and arriving at a place where it does feel like we have true solidarity, right? Because again, I think that could be a positive byproduct of the lumping that we tend to get put into, especially when looking at the percentages of our respective populations in the state, 8% here, 7% here. If you add all our percentages up, like, okay, it’s a little bit more weighty, right? And that could mean something, in terms of moving some things forward, in terms of our respective contributions. But what do you think needs to happen for there to be that true solidarity in Wisconsin? So what do you think that we need, and what would you also like to see from the larger community who identifies more as the dominant culture, in terms of how they can support?

[Johnathan inhales deeply]

[exhales deeply] Johnathan: I think that in order for any of us to move forward, we have to understand— The reason why race is important in Wisconsin is because we are going to interact with individuals who might not look like us or them, right?

Angela: We’re likely to.

Johnathan: And understanding race allows us to check our bias, right? And so—

Angela: And that’s a good callout because we might not assume that we even have biases.

Johnathan: Right, exactly, and we all have them. It doesn’t matter, right? Like, actually, that also is, like, a thing that transcends race, right?

Angela: Absolutely, ’cause they’re essentially just mental shortcuts.

Johnathan: Exactly.

Angela: Like, they help our brains to operate efficiently. They can just be rooted in negativity. So, yes, sorry.

Johnathan: Right.

Angela: Psychology brain starts kicking in, go ahead.

Johnathan: Exactly, and I think that if we are, like, how do, you know, and I think being a Puerto Rican person, again, I could say it all day, but we’re African, we’re Indigenous people, so we’re Boricuas and we’re Spanish. And I think as a person, like, as a Puerto Rican person, I think we are in a really good position to understand the plight of each.

Angela: Mm, mm-hmm.

Johnathan: Right? I really think that, like, internally, sometimes I feel like there’s an internal battle between three, three people that constantly go between, like, checking each other in one way or another, right? And I think it takes, you know, I think we need better history. We need to know our history better. We need to— There’s no people in Wisconsin that are from Wisconsin, unless you’re of the tribes.

Angela: Yes.

Johnathan: Right.

Angela: Yes.

Johnathan: And so I think it’s important to acknowledge, “Hey, we might be European, and that’s okay. We are African, that’s okay. We are Puerto Rican, that’s okay.” Like, it’s okay to not necessarily be from here, at this point, right? And with that, the better we understand race, the better we understand bias, and the better we understand bias, the better we get along. Right? How does that happen practically? How do we make that happen practically? How do we help people move into spaces of curiosity versus hostility?

Angela: Mm-hmm.

Johnathan: I feel like that’s kind of been my place in our community, has been, you know, this…

Angela: Like a bridge?

Johnathan: Yeah, so how can we help make bridges? Yeah.

Angela: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm. Which it sounds like arriving at that place of curiosity means that there isn’t fear attached to certain interactions, or the perception that the presence of certain groups of people means something less for me, or less for the people that I care about. So if all of us are contributing to the richness of the human experience, then okay. Yeah, tell me more about yourself. Let me, you know, try to release some of the things that I might have been taught that weren’t necessarily true, and just opened myself up to a new experience, versus maybe seeing you as inherently threatening or taking away from, you know, something that I value. But that’s, you said that’s that inner work that we all have to do on a regular basis to check our biases and try to rework how we view other people. But also appreciating the space that you occupy, in terms of I can be present, I can help to dismantle, maybe, prior held perceptions people had, and kind of be a representative for those who might never have access to the spaces that I’m in. So definitely appreciate that role that you play.

What would you like to see for Puerto Rico?

Johnathan: You know, any Puerto Rican, and I might be bad for saying this, but any Puerto Rican who has this idea that they want statehood, they just don’t understand our history.

Angela: Mm.

Johnathan: Right. How could you want statehood after everything that happened to our people?

Angela: [exhales] And that becomes a trickier conversation, right? Because while I can understand the preference, because there are benefits that come with that, that you all presently don’t have. But then you’re right. That means a connection to your oppressor, essentially.

Johnathan: Yeah, we’re complacent in our own abuse.

Angela: So it’s—

Johnathan: Yeah, and so, but… It’s a big, it’s a big discussion, or I think it will be bigger. And at least I’m hoping that even this discussion, being a part of the dialogue, right, and hopefully helping someone realize that we have to learn more, right? We should learn more before we speak, right? Or try to, or try to have an understanding, right, of this thing we call, you know, being alive, and, like, where we fit in it all, right?

Angela: Mm-hmm, so, thank you for your time today, Johnathan, and for just the wonderful discussion about your experiences, both of your homes, and just helping to broaden our understanding around race and ethnicity and why that all matters when it comes to the state we now call home.

Johnathan: Yes, thank you for having me.

Understanding racial identification means diving into the complexities of how we see ourselves and how society responds to those identities. It’s not always easy, especially when your identity is questioned or rejected. But these experiences shape the broader conversation about why race matters. By exploring these challenges and the impact they have, we can start to build more inclusive spaces where everyone feels seen, valued, and understood.

Watch additional episodes and content at whyracematters.org.

[bright music]

Announcer: Funding for Why Race Matters is provided by Park Bank, UnityPoint Health Meriter, UW Health, donors to the Focus Fund for Wisconsin programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us