Public Safety

"The system isn't broken. It's doing exactly what it was designed to do."—Aaron Hicks

Public Safety

Public safety remains a relevant issue globally, and specifically within the United States when layered with racial inequality. But how do we understand the need for safety and think about the idea of it when considering the Black American perspective? Aaron Hicks of Focused Interruption gives his thoughts on the issue.

GUEST

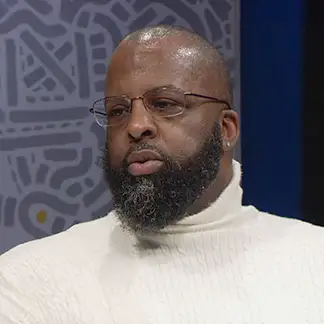

Aaron Hicks

Aaron Hicks is an outreach worker for Focused Interruption, an organization that uses a holistic approach to reduce generational trauma by providing evidence-based intervention and prevention services to the people, neighborhoods, and families most impacted by gun violence. Hicks also does public speaking events and uses his own experience around incarceration to help members of Black communities to navigate post-incarceration life and find self-value.

TRANSCRIPT

[orchestral music]

– The following program is a PBS Wisconsin Original Production.

– Public Safety remains a relevant issue globally and specifically within the United States when layered within the context of racial inequality.

But how do we understand the universal need for safety and think about the idea of safety differently when considering the Black American perspective.

Let’s find out why race matters when it comes to public safety.

Gun violence is rising.

The number of gun murders nationwide rose 45% between 2019 and 2021.

In Wisconsin, some Black neighborhoods are affected by community violence.

When we say community violence, we’re talking about violence that happens in public places like a busy street or a local park.

Policies like redlining and under-resourcing as well as disparities in poverty, education, and incarceration continue to disproportionately impact Black neighborhoods with community violence.

A 2021 CDC study found Black men and women have the highest age-adjusted rates of firearm-related homicide.

It’s important to remember every victim of gun violence has family, friends, and loved ones.

These injuries and deaths are heartbreaking and can cause generational trauma.

In this episode of Why Race Matters, we’ll speak to Aaron Hicks of Focused Interruption about community-based gun violence and prevention, and why race matters when it comes to feeling safe.

How are you doing today, Aaron?

– I’m well, thank you for asking.

– Appreciate you joining us today on Why Race Matters.

So, can you tell us about your work, about Focused Interruption for someone who has maybe learned about or is learning about the organization for the first time?

– Yeah, so actually, I’m a outreach worker for Focused Interruption.

Our outreach team primarily work with shooting victims, and victims of violence, with the exception of domestic, so stabbings, shootings, those type of things.

– So, it’s part responsive, part preventative?

– Absolutely.

– Okay.

And with a focus on the Black community, specifically in Madison?

– That’s correct.

– Okay, okay.

And is that because the trends around gun violence are different?

– Aaron: It is.

– For the Black community compared to larger Madison.

– Aaron: It is.

– Okay.

– And it’s been a growing thing here in Madison and it’s, we just know that, like, it’s on our watch.

Prior to any of this work that I was doing, I was incarcerated for a period of time.

And so, my mission has been how do I give back?

How do I turn my mess into my message?

And so, through utilizing Focused Interruption, it gives me a outlet to be able to work with those individuals who are struggling or going through certain issues that I can relate to.

– Wow, I appreciate that, ’cause I was gonna ask you, what’s your origin story?

Like, how did you get into this work?

So, it sounds like your own personal background is a driver behind you doing what you do in Focused Interruption.

– It is.

– And are you from this area or from the state?

– Well, I’m originally from Milwaukee.

– Okay.

– You know, Madison is so interesting because we have not really tapped into what this issue is.

And race plays a major factor in all of this.

– Absolutely.

– And with that being said, we’re here in Madison.

It’s something that we really don’t like talking about.

We tippy-toe around it.

It’s something that we have never just head-on had a conversation about to the powers that be.

– Hmm.

– And so, I think strongly the more people start to get involved and start to have these conversations around this, it changes those dynamics and those narratives.

I understand that, you know, these areas are impoverished areas and I also understand that, you know, poverty is a construct, right?

This can be stopped.

It can be changed.

Now, it’s a matter of if it’s not being changed, the question has to be “Why?”

– Angela: Right.

– Right?

‘Cause it’s not that we don’t have the means to change those things.

You know, when people are eating, crime goes down, right?

And when people are not eating, crime goes up and it don’t matter what race.

– Right.

– You know?

And so, that same principle applies even with violence.

And the thing about violence, what’s so interesting is there is no race or color on violence.

So, you know, why wait until something happens or something is on your front door?

Why not address it before things get out of hand?

Because the one thing about violence, it’s kind of like because it’s so chaotic, sometimes it spread and sometimes it wind up in places that you didn’t expect it to be.

– That is very true.

And why do you think that, you mentioned that we tiptoe, I’m assuming the ‘we’ is the Madison as a collective.

– Yes.

– Wanting to address certain things.

Why do you perceive that there is a tiptoe response to this topic at times?

– Because here, we don’t really like to ruffle feathers.

We don’t like to cause any waves and everybody wants to be received and accepted, and, you know what I mean?

So, for those reasons, it’s almost as if we want to ignore it.

You know, when I read articles about Madison being one of the greatest places to live in the country, you know, that question is always asked, “For who?”

Right?

Because that is not applicable for Black and Brown people at all.

– When thinking about best places to live, best cities to live.

But there are these pockets of challenges that present.

And it can be easy to interpret those challenges as belong to a particular group, and not something that more broadly we should have shared ownership around as a community.

So, how do we have a broad community response and not let that be something that, you know, Focused Interruption does that.

– Right.

– The rest of us, because we’re unaffected.

– Right, right, right, right, right.

– We don’t deal with that, right?

– Aaron: Yeah.

– And that really gets to the heart of at what is the cause of these issues when it comes to public safety.

I remember one analogy I used to use in class I used to teach was there’s a connection between increases in violent crimes and ice cream consumption.

Does that mean the more ice cream you eat, the more violent you become?

– Right.

– No, it means that both things are being driven by the hotter it is, the more likely things are about to pop off.

– That’s right.

– And you more likely to eat ice cream.

– Aaron: That’s right.

– Right?

So, thinking about what are the things that might be present in communities that also happen to be more reflective of communities of color that we really need to get at and address, because in doing that, we make Madison truly that city.

– That’s right.

– That everyone desires to be living in.

– That’s right.

It’s hard to say it’s one thing.

Because one thing that’s driving– The people are hurting, you know?

Period.

And so, we understand the concept when people are hurting, hurt people, that’s what they do.

They hurt other people.

And why I think it’s so valuable to have that deep conversation right here is because I think that we can start the process of people starting to heal, right?

Because people want to be made whole.

But what does that look like?

Well, it’s about really being able to talk about things that most people have not been talking about, right?

Some of the hurts, some of the habits and hang ups that people have had with the powers that be, whether it be the university, whether it be our legislators, you know what I mean?

But we have seen people make promises and not stand on their promises.

And so, for those reasons, that leaves a nasty taste in people’s mouths.

And so, really just, my model is just real simple.

It’s just like, say what it really is, you know what I mean?

Let our community know what it is.

If this is not the agenda, and this is where you want it to stay, at least say that to us.

We should have the right to at least know that much.

Don’t make it seem as if, you know, we are progressing, and we’re changing these dynamics.

You know, we’re saying it verbally, but no action, no skin in the game, no nothing.

We’re not putting funding to any of these things, you know?

– Mm-hmm, wow.

– And it just makes me marvel how when you talk about changing certain narratives like that, you’ll hear words like “resources are scarce.”

“We don’t have the means to do that.”

What’s so interesting about that statement is that when it’s time to lock somebody up, we have the means to be able to do that.

If we need to go to war, we always got the means to be able to do that.

But when it’s time to help someone, we don’t have the means to do that.

So, that becomes an issue in itself, and it’s like, we will go the extra mile to hurt one another before we go the extra mile to help one another.

– That is true.

And like you said, there does seem to be less of a scarcity of resources when it comes to like reactive sort of responses.

– Aaron: That’s right.

– But the prevention, the holistic approaches aren’t always seen as the go-to responses at times.

– That’s right.

– And that, to me, I appreciated that seemed to be that the theme of Focused Interruption was how do we holistically respond to gun violence?

Like there are these ways in which we are, yes, reacting after something happens, we go to the hospital, we connect with families, you know, we do things in the community, but then there’s also the prevention side of how do we prevent even needing to do those reactive sorts of things.

– That’s right.

– And it sounds like there’s a, from what you just shared, there’s absolutely accountability on the part of the powers that be.

– That’s right.

– On the part of legislators, on the part of people who make funding decisions around how they invest within our community.

Because our community is most likely to be impacted by this very real public safety issue, I’m also curious what you would say to members of our community, or just the community as a whole who are like, you know what, we wanna take that power and not wait for those who are already in positions of power, or those who already have money to decide to care or decide that they’re ready to invest.

– I mean, there’s a few things you can do.

One is just get involved, you know.

And it doesn’t have to be with Focused Interruption per se, but get involved in the community and know the matters that’s going on around in the community.

Right?

You know, part of me being incarcerated, I didn’t really know that I was valuable.

I’m just being honest with you.

I didn’t know that I brought value to the table and understanding that I do, that’s what I promote and push for other individuals, knowing that they have, letting them know that you have value, right?

Letting them know that what they do matters.

Their voice matters, right?

So, whether it’s getting involved, whether it’s donating, whatever it is, don’t sit on the bench, get in the game, get involved, and if you see something, say something.

Right?

But we can’t do this by ourselves.

You know, it takes a village.

Despite what the powers of be are doing, we still can make a difference.

You know, my desire is to change the world, right?

But what I started to realize is when you change one life, you’re changing the world.

– Yeah.

– And so, just know, like whatever you do, whatever seeds you plant, you’re making a difference.

– Absolutely.

And do you have thoughts around thinking about the young people angle of this?

What does that look like?

– We have to allow them to see more positive stuff that’s taking place.

Because that’s not being highlighted.

Change, when people are, you know, doing things that’s impacting the community, we don’t highlight that like we highlight, you know, and everything that we are involved in, whether, you know, it’s this or whatever, a lot of things are very fear driven.

And because it’s fear driven, that’s how nobody wants to call out anything.

Nobody wants to say anything.

They’re afraid.

If I say this, then there may be consequences and repercussions.

So, nobody says anything because they want to keep their livelihood.

I wanna be able to send my kids to college.

And if that means me not saying nothing, then let it be.

– Mm.

And so, thinking about your own journey of recognizing your value, how would you recommend we go about supporting that?

– Hmm.

– For young men and women who don’t see their value, and so, their life is treated as though it’s disposable.

When we know it’s not.

– I think that it’s a couple things, but one is what happened for me was it was consistency more than anything else.

People giving me affirmations, letting me know, like despite all of that, I’m not looking down on you and I still see the greatness in you.

And I just believe when greatness calls out the greatness, it just receives it, accepts it, and you know what I mean?

But they’re not hearing that they’re great.

They’re not hearing that they’re valuable.

And they need to hear that, you know?

And it usually, it’s supposed to start at home.

– Mm-hmm.

– And when it’s not happening at home, that starts to transcend outside of, into the community.

And the community starts to give you identity when you don’t have an identity, you know.

He’s a fool, or, you know, he get money, or he, you know, all of these different things.

And so, you walk according to that because you don’t know who you are.

And if you don’t know who you are, you don’t know exactly where you’re going, right?

And it ain’t until you have an identity that you find your direction.

– That is so true.

So, that foundational piece of knowing who you are.

– That’s right.

– And that being supported and reinforced in a positive way by the community.

– That’s right.

– This didn’t just show up.

– No.

– This has been ongoing for, dare we say, centuries and perhaps not violence in the same way that we experience it now, but the identity crisis piece, that’s not new.

– That’s right.

– Because when you think about the Black American experience in this country, we’re stripped of our identity from day one.

And a different identity was forced upon us.

– Aaron: That’s right.

– And unfortunately, a lot of us have internalized that negative view of self.

And so, if we view ourselves as less than and then, we view people that look like us as less than, well, then, it’s easy for me to kill you.

– Aaron: That’s right.

– Or not value my own life because the world around me tells me I have nothing to contribute, I have nothing to offer.

– That’s right.

– And we know that’s farthest from the case.

So, it feels like that’s such an important piece in a city like Madison, where you are less likely to see yourself reflected back at you.

It feels like we have to go harder with what that looks like for young people to say like, “Hey, you matter.

“Here’s positive representations of who you are, “what you can be.

“How we can support you with whatever path you are interested in for yourself.”

– With that mindset of “When I wake up, “I have to be able to see a young person and share something with them.”

– I didn’t have that.

– Angela: Right.

– You know what I mean?

And I understand what that feels like, right?

And, you know, it took some extreme things that happened in my life that ultimately broke me, but it allowed me to be able to see me and value me.

– So, in thinking about the layers of what we can do, right?

So, you try to be very solution oriented.

– Yeah, definitely.

– You know, and it can be tricky because there are very real issues that impact the Black community in our state, and not just in our state.

We know it’s a national issue, but we’d like to contextualize, bring it down to Wisconsin.

In thinking about poverty, education, incarceration, what sorts of activities or things have you personally or Focused Interruption as a group, what does that look like for you all in those different systems around gun violence?

Either the response to it or preventing it altogether?

– Yeah, I have a quick question.

– Angela: Sure.

– If I could ask you first.

– Oh, go ahead.

– Do you feel like our system is broken?

– You mean, just in general?

– Aaron: Just in general.

– Okay.

And our system, just, like, how we live our lives?

– Run and do things.

– I think it’s working for those it was designed to work for.

– That’s a good answer.

[Angela laughs] But it’s important to answer it that way because most people, whenever I’m in a class, I ask that question, you know.

And most all hands go up.

– That the people think that it is working?

– That they think that the system is broken.

– Got it, okay.

– So, when you think a system is broken, your mind goes to, let me try to figure out how we can fix it, right?

Most people don’t really know that the system isn’t broken.

It’s doing what it was designed to do.

That’s why you see it.

That’s why, like, we are the only race of people who have been enslaved on this land.

Right?

So, it is very intentional, and then, to change some of these narratives has to be, but we have to have dialogue about these things because these things really did happen, right?

And people are very hurt and broken from a lot of this stuff, right?

And it ain’t until we are ready to shake out some of our dirty laundry and really talk about these things, right?

You change the trajectory of how life can look.

And so, on an individual level, I get a lot of time to spend into the university.

And by doing that, I get to just challenge some of the professors just to see things in a, you know, what we created was, we have this thing, it’s called “the best of both worlds.”

And it’s about bringing the academic world together with lived experience, right?

And so, it changes how you look at things because most people, only they understand our issues from a very academic standpoint.

They didn’t never have to live it.

I was in a meeting and it was around gun violence and I just kind of sit back and listen, and they were just intellectualizing gun violence in the way that they do, right?

And so, I just asked a question.

My question was just strictly, who wakes up or goes to sleep to shooting?

No hands went up, but I put mine up.

And what I really was conveying to them is like, you should not be discussing the subject without the subject matter being there.

That makes sense, right?

It’s like they can intellectualize poverty or they can intellectualize homelessness and never had had that experience.

– Angela: Right.

– So, being able to share and get them to see things through a different lens and vice versa.

I get to see through their lens, as well.

But it’s been eye-opening and it changes perspectives and narratives and it gets people on different trajectories of even their work.

Those people have to be able to not only hear it, but they have to also see it.

– Right.

And I hope that one of the takeaways when people are having these conversations with you is balancing out the statistics and what the numbers say about your communities, about our communities, and not viewing them as all of any one thing.

Just like any community is not all of one thing.

– Aaron: That’s right.

– It can be easy to view our communities as all a negative.

– That’s right.

– Because statistically, we are more likely to dot, dot, dot.

But those numbers don’t tell the whole story.

It doesn’t even convey the beauty within those communities that you may perceive.

– That’s right.

– As unsafe.

Because the flip side of that is you can have the most beautiful gated community that does not feel safe to someone that looks like us because of how we may be received.

– That’s right.

– In those communities.

Or how we may feel more unfairly targeted.

Am I gonna get the police called on me?

Or if my kid goes to the basketball court, does that elicit a different response versus if just any kid in the neighborhood goes to the basketball court?

So this idea of safety is not, I don’t think it’s equally understood, because it’s not equally felt in the same ways.

Yes, gun violence makes all of us feel unsafe, but I don’t think it’s always understood how psychological safety… – Mm-hmm.

– …is not something that we always have the luxury of experiencing in our home state, in our home cities because of the perceptions that some may have about who we are, what we bring.

– Yeah.

– I have a question that I’ve been asking as my final question.

– Okay.

– For all of our guests this season.

And that is, as it relates to this topic we’ve been discussing today, public safety in our state, what does success look like to you?

– It looks like when that word is applicable to all parties, to all creeds, races.

Everyone should feel safe, right?

It shouldn’t be limited to, because ultimately, though I do all the work that I do, I can’t tell you that I feel safe.

– Mm.

– Right?

And I would be lying to you if I told you that.

I don’t always feel safe, not even here in Madison, because I understand that it has not, safety has not, it’s not a net for everybody, right?

We can justify certain things on one end, and then, on the other end, that’s a crime.

And so, that don’t feel right to me.

And it’s like when we change those type of things, that’s when safety is, like, if I commit a crime, then I should be held accountable.

But whether it’s the governor, whether it’s the lieutenant governor, whether it’s whoever, and they commit a crime, they should be held just as accountable as I would be.

And right now, that’s not the case.

– Thank you so much for your time today, Aaron.

– Man, it’s been a blessing.

I appreciate you and thank you kindly for having me.

– You’re very welcome.

Public safety is a right that we should all be afforded, but providing safety in ways that are felt across racial lines and that considers the racialized history and resulting generational trauma in the United States and within the state of Wisconsin specifically require special care and expertise.

Thank you to Aaron Hicks and others who are dedicated to this important work.

Watch additional episodes and content at whyracematters.org.

♪ ♪ [upbeat music]

– Announcer: Funding for Why Race Matters is provided by UnityPoint Health Meriter, Park Bank, donors to the Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us