[bright music]

Announcer: The following program is a PBS Wisconsin original production.

Angela Fitzgerald: Critical race theory, or CRT, isn’t a new framework or way of thinking, but it has received renewed attention due to anti-CRT legislation created across the United States. So what is CRT, exactly, and why is it producing such a strong reaction in some states, So much that some lawmakers are pushing to ban teaching it in schools? Let’s find out Why Race Matters when it comes to history, racism, and education.

[upbeat music]

Angela Fitzgerald: Critical race theory, or CRT, can be a controversial buzzword today. But that wasn’t always the case. In fact, it isn’t even a new concept.

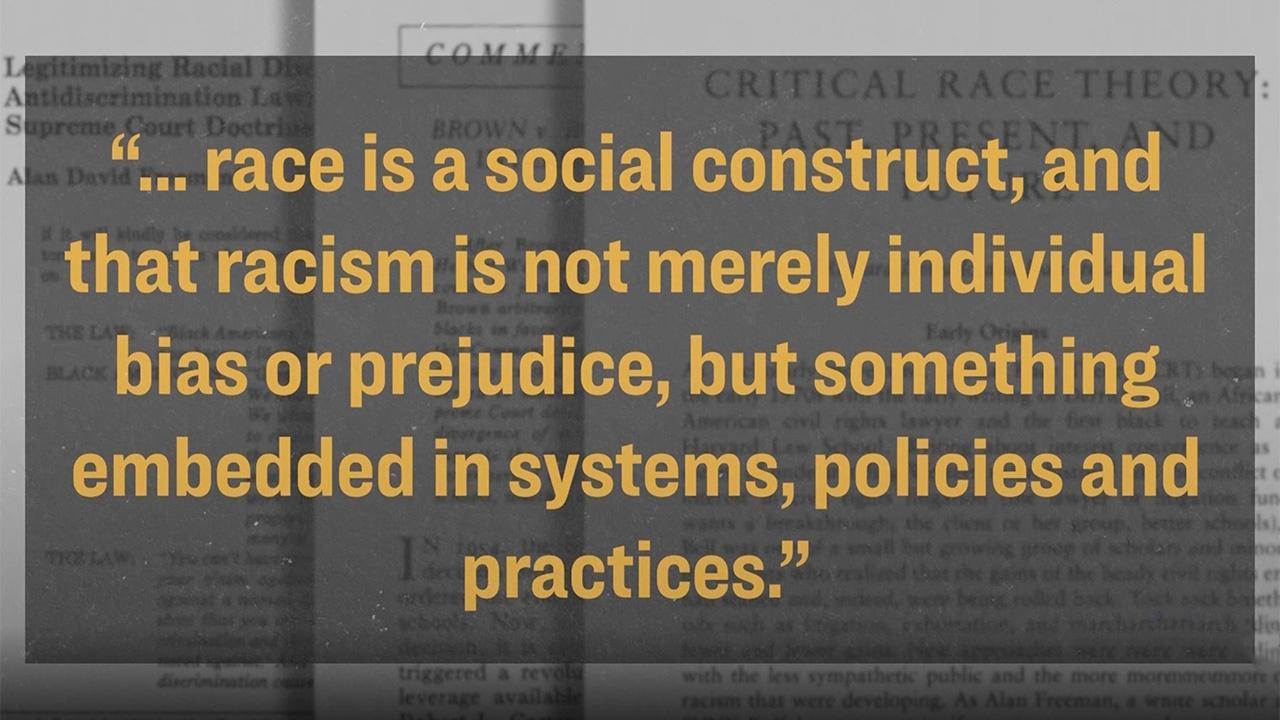

CRT dates back to the 1970s and ’80s as a framework for legal analysis that was created by several legal scholars to suggest that “race is a social construct and that racism is not merely individual bias or prejudice, but something embedded in systems, policies, and practices.” CRT suggests that because racism is so deeply ingrained in the fabric of our nation, even well-intentioned decisions made by individuals can help to fuel racism.

And for some, therein lies the perceived controversy, resulting in the creation of anti-CRT legislation. In Wisconsin, the Legislature passed a bill in January 2022 that would limit the discussion of racism in K-12 classrooms, including any teaching that “an individual, by virtue of that individual’s race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.” The bill was vetoed by Governor Tony Evers.

Critics of anti-CRT legislation say that if America desires a more equitable future, then we must be willing to acknowledge the atrocities of the past and their influence on the present.

National Academy of Education President and Professor Emerita at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, joins us to share more about the importance of CRT and its application in and outside of the classroom. So, Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, thank you so much for joining us today.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: My pleasure.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, can you start off by telling us a little bit about yourself and the work that you do?

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, I am Professor Emerita of the University of Wisconsin- Madison. That’s just a fancy way of saying I’m retired. But I will confess, I am failing at it.

[Angela laughing]

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: I am the world’s worst retiree. I’ve been fascinated by the education of Black people in this country because it’s such an incredible story. And so, where I see inequities in that education, I always want to kind of probe it and explore it and try to make sense of it.

Angela Fitzgerald: I appreciate you coming in to talk with us about a very important topic. For some, it’s the topic when it comes to race right now. CRT.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, and I want to be clear that the context that we are in right now, on the heels of some horrific massacres of people, mostly people of color, and clearly the one in Buffalo being driven by racial hatred, it’s very timely to talk about this particular topic.

But rather, just saying to someone, “Oh, I study critical race theory,” or “What do you know about critical race theory?” I often start with the question, “Tell me how you explain racial inequality?”

Angela Fitzgerald: Mmm.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Because I think the explanation that one has really kind of makes them, you know, puts them in a context for understanding the world. So, if your explanation is, “Well, people just need to work harder.” Millions of people need to work harder?

I mean, think about it. If you start off by saying, “Well, there isn’t any racial inequality,” then I don’t actually think I can have a debate with you because we don’t see the world the same way. On almost every social benefit, whether it is health, wealth, education, employment, we can see racialized disparity.

So, how do we explain it? In a classroom with students, typically graduate students, I want to be clear. I would probably say something like, “Well, it’s not as if we haven’t had explanations.” We have.

From the time Black people arrived on these shores to about the mid-20th century, 1950s, our explanation was pretty much biogenetic. So ingrained in our thinking that many universities, many colleges, had departments and programs in eugenics. We said that was a science, that this group of people is biogenetically inferior. Now, I would imagine that a lot of thinking people did not buy into that well before the 1950s.

Angela Fitzgerald: Hopefully.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: But I use the mid-1950s as a marker because it’s at this point that we have the Brown decision. And Brown is a landmark decision. Everybody knows Brown vs. the Board of Education.

However, from a critical race theory perspective, we don’t see it merely as an education decision. We see it as a foreign policy decision. Because you have to put the legal cases, the Supreme Court cases, in a broader context.

1954 is the heart of the Cold War. And part of the propaganda that the then Soviet Union is using is to say to non-aligned nations like Angola or India. “You don’t want to be associated with the United States. Look what they do to people who look like you.” So that there’s all these examples of lynching and dogs being sicced on people, failure to allow people to vote. So there is great pressure on the nation.

Angela Fitzgerald: Right, we looked bad.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: To look better, right?

[Angela laughs]

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Because the Soviets are exploiting this. I mean, you can find editorial cartoons, you can find op-eds all about “Look how the United States treats Black people.” So, it’s not, it’s why not only did the decision have to come out in favor of Linda Brown and the plaintiffs, it needed to be unanimous. It needed to make a statement. So at that point, we’re saying the problem is not biogenetic. The problem is lack of opportunity. That’s a pretty good explanation.

Angela Fitzgerald: It is.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Unfortunately, not long after that, Richard Nixon’s administration, and, in fact, I wrote a paper about the Brown decision in which I was able to find a statement from one of Nixon’s, part of his administration, H.R. Haldeman, who was also disgraced in the Watergate scandal. But he tells, you have Haldeman’s diary in which he says Nixon has told Mitchell, that’s the Attorney General, to start filing cases to roll back Brown. And keep filing it, filing them until it’s totally rolled back.

And so, we have all these cases that come back. We have Milliken, we have Dow, we have San Antonio vs. Rodriguez. So the “opportunity” explanation’s seemingly not holding up. Another example is voting rights. 1960s, right? So, that’s an opportunity.

What is happening now? Affirmative Action. It’s a Lyndon Johnson initiative. And it has been fought over and over. The Fisher case, the Gratz and Grutter cases out of Michigan, So critical race theory comes along, and it comes along in the late 1970s.

Angela Fitzgerald: And that’s part of the frustration for some is that this isn’t a new argument.

– Dr. Ladson-Billings: No.

Angela Fitzgerald: This has been around for decades.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: No. And so when people say, “They’re trying to foment a revolution,” I always say, “This is the slowest revolution I have been a part of.”

[Angela laughs]

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: I will be dead before we have any movement.

[Angela laughs]

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: But critical race theory comes about in law schools. At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where they held these critical legal studies conferences, those were folks who said, you know, the way that law is taught and the way that we understand it doesn’t take into consideration the situation and the condition of other people, other than people who were already well established. And so, it was mostly around people who were poor, women. And it was a group of Black legal scholars, as well as other scholars of color, who said, “You guys have forgotten about race.”

So, the critical race theorists emerge in these Wisconsin workshops. And what I find really interesting is people always want to make it a sort of Black-white issue, but I show people that among the major proponents are people like Richard Delgado, Mari Matsuda, Sumi Cho, Tomas Rivera. I mean, these are all folks who have done work in this area. They’re not Black. They’re trying to figure out how do we explain persistent generational racial inequality?

Angela Fitzgerald: So, in short, for someone who’s never heard of CRT or maybe has heard of it, but doesn’t really know what it means, what’s the simple definition that you use to help people understand?

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, you know, I try to tell people it is a legal look at racial inequality. Its whole point is to try to explain the inequality, try to make sense of it. Because it really, you know, after all of these years of having been in this nation, you know, some of the longest standing people in the nation are Black. You know, in some ways, I often say who’s more American than a Black person? Because we have deep and long roots here. So, I think that the whole point of critical race theory is to try to make sense of why the inequality persists.

Angela Fitzgerald: So, would you say that that is the current sort of reasoning that exists? Like, we’ve graduated from all of these other points in time we had other ways of thinking about inequality, to now it’s systemic. There’s an issue with the system.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: And we’re saying it out loud. I don’t know if you remember, but not too long ago, one of the major advertisers, I can’t even, I won’t say it ’cause I’ll get it wrong, but some, one of the major advertisers did an entire series called “The Talk.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Mmm.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Where Black parents, you’d see these little snippets where Black people would tell their children, “If you get stopped by the police, be polite. “Don’t let anybody call you such and such word.” I mean, okay, when did we all get together and have this conversation?

[Angela laughs]

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: It turns out that that’s part of our systemic understanding of this is the way it works. That yeah, you do expect to have someone follow you around. Now, I remember teaching a class where students, you know, and my work is not to make students think like I think. My work is to make sure they think. So I’m happy to hear a well-reasoned, well-thought-out, well-substantiated conservative argument about something. More so than a knee-jerk liberal one. I want you to be thinking.

So we had a discussion once where a young lady talked about she was in a store, a local store, purchasing groceries, and she’d left her checkbook. And the manager or the cashier, I’m not sure who, told her, “Oh, not a problem. “Take your groceries and when you come back by, you can pay.” Well, a Black student in this class said, “Well, that wouldn’t happen to me.”

[Angela laughs]

And she said, “No, it would, it would,” you know, “they’re really nice there.” And he says, “I’m telling you it would not happen.”

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: So they went back and forth and so he said, “Let’s do this. “Because I do live in your neighborhood, you know, “that’s, we know each other. “The next time I need to go to the store, “I’m gonna call you and I’m gonna have you go with me and I’m gonna purchase what I need to purchase, “go through the cashier’s line, “but I’m going to say that I don’t have my wallet.” They did it.

And as soon as he said he didn’t have his wallet, he was told, “Okay, well put the groceries “over there on the side and then when you, “you go home and get your wallet and then come back.” So she was mortified. Because it was this local family, it wasn’t a chain, right? And it was like, “Why would they let me just, you know…”

So, it’s those kinds of “aha” moments. Often, some colleagues and I say, you know, we’ll call each other about something and someone will say, “I had a CRT moment.”

[both laugh]

In other words, it’s just one of those things that’s happened again.

Angela Fitzgerald: I so appreciate that example. Not only because it’s relatable, but because it does help to kind of simplify the conversation. Although I can see some people taking that, especially the grocery store example and saying, “Well, oh, that particular person that was working is racist,” versus calling attention to the system.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Mm-hmm.

Angela Fitzgerald: So how would you help someone kind of delineate between like there’s individual racism, yes, we don’t want to ignore that, but systemic racism is way more insidious in some ways because it can fall under the radar in ways we don’t always recognize.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Well, I don’t deny individual racism, but racists grow up in a context. So let’s go back to the Buffalo massacre and that, that individual, yes, I’m gonna buy that he’s mentally ill. Anybody who would shoot up people like that is mentally ill. But what’s the context that was feeding his mental illness? Well, when we check his computer, he’s in all kinds of hate groups. When we see the manifestos, what his whole point was. So, it’s a both/and situation. There are individual people who are racist, but there’s a context that feeds into that racism that happens systematically.

Angela Fitzgerald: And so I brought up the individual racism part because I feel like that’s somehow tied to the opposition, like the current opposition. Because like you mentioned, CRT is not new. It’s been around for decades. It’s provided a legit explanation behind why there are disparities still because some people like to believe that that was so long ago. Why are we not X, Y, Z? Well, the system didn’t change this whole time, so why would things generally improve for a group of people the system was never designed to benefit? But I guess I’m curious, from your vantage point, why now?

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: So, let’s be clear. Much of what people are, quote, “against” is not critical race theory. When you say, “Oh, I’m against anything that’s, you know, that’s anti-racism.” Well, that’s really not critical race theory. We’ve been doing anti-racist workshops for a very long time. When you say you don’t want to have any discussion on race, when you say we don’t want white children to feel bad, You know, when I first heard that, I thought, “Well, my God, where were you in the 1950s and ’60s when I was in school?”

[Angela laughs]

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Because I had to sit through Honors English classes reading Mark Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn” with the liberal use of the N-word and all of my white classmates sniggling and giggling. Right? I had to sit through Margaret Mitchell’s “Gone with the Wind.” Nothing about education is about just making you feel comfortable. Sometimes we learn the most in the midst of discomfort. So I think what’s happened is this broad net has been cast and if you go back and look at some of the architects of the anti-CRT work, you see the strategy was brilliant. So you have someone like Christopher Rufo, who is at the Manhattan Institute, who says, and I want to make sure I say this pretty carefully, but he says, we’re going to take all of the cultural insanities that Americans dislike. Now, think about that. What’s a cultural insanity and who are the Americans?

Angela Fitzgerald: Right.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: We’re gonna take all the cultural insanities that Americans dislike and lump them into the category of critical race theory. We’re going to turn the brand toxic.

Angela Fitzgerald: Mmm.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: So now anything that deals with race, inequality, diversity, equity, inclusion, now all critical race theory. So, when we can’t talk about all of history, as James Baldwin says. He says if you feel compelled to lie about any part of the history, you’re likely to lie about it all.

Angela Fitzgerald: And that’s the danger, kind of, when you mentioned the danger of kind of compromising how we approach education and not only demonizing history, but also demonizing the explanations that are made available as to why, why things are the way they are.

So then you have students coming into classrooms and teachers not being equipped to even discuss what’s happening right now. So like, what can we offer if we can’t talk about the reasons why these very impactful, triggering, traumatizing things are happening without those tools that we’re saying, no, it’s illegal.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: Right. You know, and our founders, you know, these are really smart guys. These are smart men. Thomas Jefferson’s someone I just find fascinating. I’ve got good things to tell you about Thomas Jefferson. But there’s contradictions. Because at the same moment he is writing these magnificent words, “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” he’s got a woman, an enslaved woman, with whom he is procreating. I don’t know what the nature of the relationship is, but I know that in his notes from Virginia, he talks about Black people not being anywhere equal to white people and that the best thing we can do is just get rid of them. Whoa, whoa, you’re making more of them! You know?

So there is this incredible contradiction. Should I not say that George Washington was number one, more interested in farming than governing and that’s pretty well documented. He rode about back and forth to his farm every day that he was in the White House. Mount Vernon was his passion. Should I not say that when he was president, and remember the capital was in Philadelphia at this time, it’s not in Washington, D.C.

Pennsylvania had an ordinance that said you could not, if you were enslaved and you came to Pennsylvania, at the end of 60 days, you had to be manumitted. You had to be set free. Washington brought his slaves with him to Philadelphia and on day 59–

Angela Fitzgerald: They didn’t stay in the city.

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings: They went back to Maryland and then they came back on day 61 and started the clock all over again.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us