Black vs. African American Identity

“Separation comes from coming to terms with your own identity and navigating the space, and understanding that it's going to be different.”—Naman Siad

Black vs. African American identity

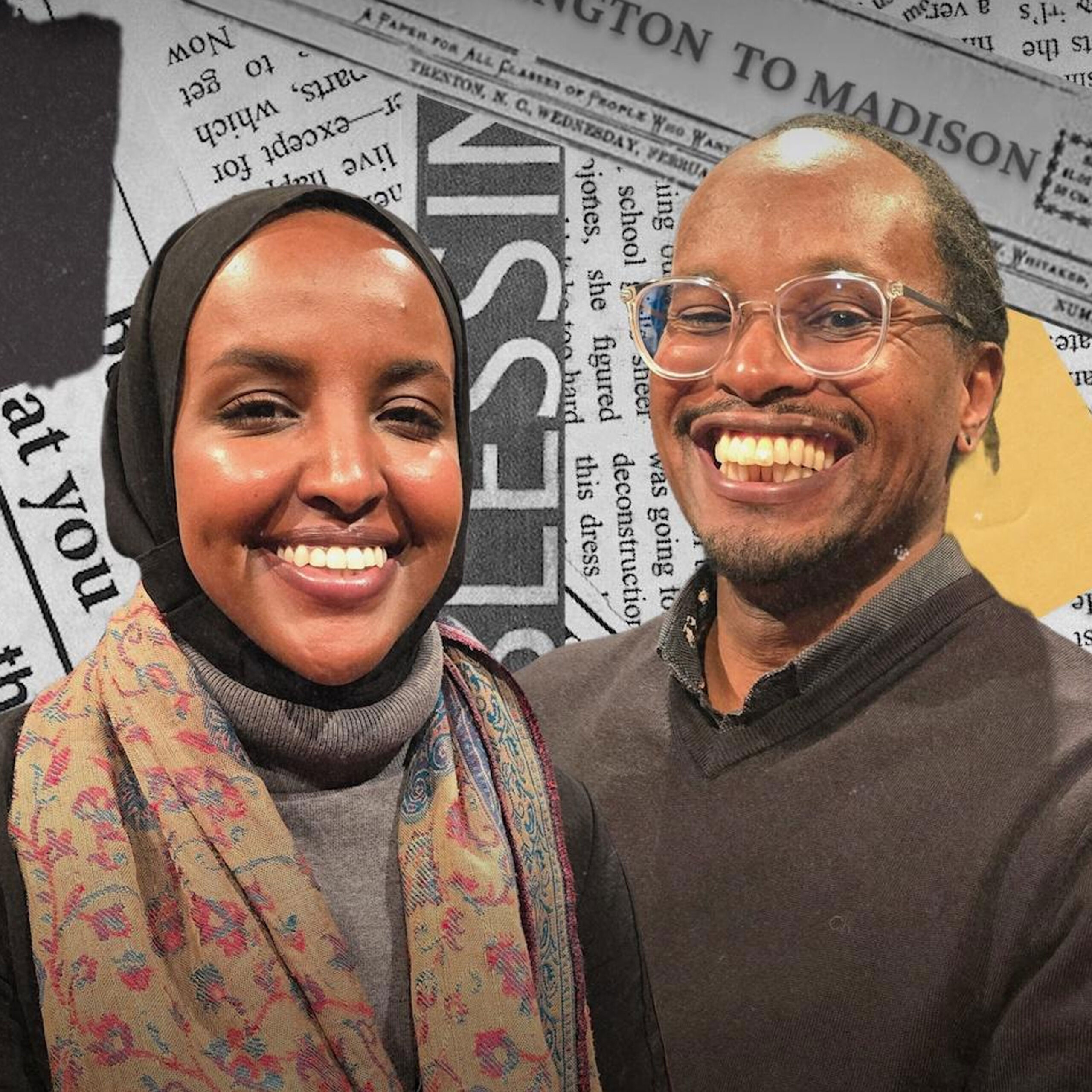

In America, identity is complex. Black and African American are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings. For some, it's about heritage. For others, culture. And for all, it’s personal. Host Angela Fitzgerald sits down with Naman Siad and Harry Kiiru to discuss identity, history and belonging within the Black community.

Subscribe:

GUESTS

Naman Siad

Naman Siad is a dedicated legal professional based in Madison, Wisconsin, specializing in general litigation, immigration, and non-profit compliance. She earned her Juris Doctor from the University of Wisconsin Law School in 2019 and subsequently completed an LL.M. in Human Rights, Conflict, and Justice at SOAS University of London in 2020.

Harry Kiiru

Harry Kiiru is a Ph.D. candidate in African Cultural Studies at UW–Madison. His research explores how Sub-Saharan African immigrants are racialized in the U.S., starting with the 1959–63 East African Students’ Airlift. His dissertation, The Culturally and Racially Body in Motion, examines how Blackness, Africanness, and migration intersect to shape identity. Kiiru’s work deepens our understanding of cultural transformation and racial identity in the American context.

PODCAST TRANSCRIPT

[bright music] – Announcer: The following program is a PBS Wisconsin original production.

– Angela Fitzgerald: In America, identity can be complex.

Take the terms “Black” and “African American,” two labels often used interchangeably, but with distinct meanings and stories.

For some, it’s about heritage.

For others, culture.

And for all, it’s personal.

In this episode, we’ll unpack the layers of identity, history, and belonging within the Black community and find out why race matters regarding Black versus African American identity.

In Wisconsin, like many parts of the country, Black communities are diverse, with individuals tracing their roots to forced migration through slavery, and others arriving as immigrants from various African and Caribbean nations.

These two groups often face similar challenges: discrimination, racism, and struggles for equality, yet how they identify themselves and how others identify them can differ significantly.

African American identity is rooted in the history of slavery, segregation, and systemic racism in the U.S.

It’s a distinct cultural identity formed by generations of Black people born in the U.S., whose ancestors were forcibly brought here.

African Americans often identify as Black because it’s a collective identity born out of a shared history, struggle, and cultural experiences in America.

But what about African immigrants?

For many, the experience of migration to the U.S. is very different.

They may carry with them a sense of connection to their specific countries, like Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, or Ghana, or ethnic groups, Hausa, Igbo, and Oromo.

But in America, they are simply categorized as Black or African American, and can experience the othering that comes with that in America.

In this episode of Why Race Matters, we’ll speak to Harry Kiiru and Naman Siad.

We’ll discuss what it means to be both African and Black in America and why race matters when it comes to community, belonging, and Black identity.

Thank you both for joining me today for our episode of Why Race Matters.

[chuckles] Why don’t we start off by doing some introductions and telling us your story and where you are originally from?

So who’d like to go first?

– Naman Siad: I could go first.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Okay, okay.

– Naman Siad: My name is Naman Siad.

I was born and raised here in Madison, but my family is originally from Somalia, and so I guess I’m a Madisonian because I can’t claim anything else.

[laughs] I went to school here, all public school, and went to UW-Madison and majored in sociology, and decided to do my legal studies here, so I went to law school here in Madison as well, and now I work at a really small law firm that kind of does community-based work, whether it’s immigration, trusts and estates.

Yeah, that’s a little bit about me.

I’ve lived in Madison my entire life, but I took some time off to live in London for my master’s, and so that was my grand escape outside of Madison, and now I’m back.

– Angela Fitzgerald: What about you, Harry?

– Harry Kiiru: So, interestingly enough, Harry is my government name.

That’s, yes, so Moreh is the name that I was given.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: It means helper, or, I mean, it’s a, it’s an age group sort of name.

And did not use Harry until I came to the U.S. [laughs] This was, so I arrived on September 1, 1997, so to Los Angeles, California, from Kenya.

I was 19 years old, and… Oh, wow, that was a long time ago.

And about maybe 10 years after that, I relocated to Wisconsin.

I’m finishing up a PhD in the Department of African Cultural Studies.

I came to grad school just to be a better parent, so raising two sons who are racialized as Black was fascinating to me, and so trying to figure out, you know, as they say when you get on a plane, you need to put on your own mask before you put on the mask to the person, your little person, so I needed to figure out how to talk to my children about what was happening in, through, around them.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: So, yes, unfortunately, my sons are my subject.

[Harry and Angela laugh] And, yes, they know way too much about race than they really should.

– Angela Fitzgerald: I mean, as long as they’ve given you informed consent, it should be fine, right?

– Harry Kiiru: [laughs] Ah, yes.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Okay.

[Harry and Angela laugh] And how would you like us to identify you, like, Harry?

– Harry Kiiru: Oh, no, no, Harry’s fine.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Okay.

– Harry Kiiru: It’s my American name, so yes.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Okay, are you sure?

– Harry Kiiru: It is on my birth certificate, so I just, yes, yeah.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Okay.

– Harry Kiiru: Yes.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Thank you for that, Harry.

Thank you both for sharing your stories with us.

And in terms of connecting to your research that you mentioned, how do we become racialized, especially the African immigrant experience.

How do you both identify when thinking about the categories that are available to you in this country and just broadly?

– Naman Siad: I think growing up, I struggled, and it’s interesting because I feel like kind of the things that you’re speaking about, about your sons’ experiences, I see in my own experience as a second-generation Somali American that was born and raised in Madison.

I think my parents and I would have very different answers because they have a lived experience in Somalia.

They were immigrants.

They came here, whereas I was born here, and I had never lived in Somalia before.

And so growing up, I had kind of a hard time figuring out how to identify, especially when the boxes are so narrow.

There’s so little choice that you have, and…

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Naman Siad: Especially in elementary school and before middle school, I didn’t wear a headscarf, and so I was trying to figure out what I was.

Nobody really knew where Somalia was.

I knew that my skin was dark, and so I was identified as Black because of that, but I remember when I first put on my hijab in sixth grade, any sort of semblance of Black identity was taken away from me because people racialized me within the Muslim context because Muslims have a very racialized identity in the United States, and so not a lot of people understand that there’s actually a very rich Islamic history in the United States dating all the way back to the slave trade, and so people have a very specific idea of what a Muslim is, and so whenever they saw me with my headscarf, they would ask me if I was Indian or Lebanese, and I just… Every time, it was a shock because I just saw my dark skin, and I just thought that people would understand that I was Black from there, so I think for a long time, I couldn’t really identify with Black culture or Black identity because I just didn’t have that lived experience, and I think I tied myself to my Muslim identity, and so I would just explain that I was Muslim and didn’t really have any sort of vocabulary or knowledge on how to introduce myself racially.

And I think it went all the way up to, I think, law school or even in undergrad.

I was a part of the PEOPLE program here in Madison, and I think that was the first time that I was around a much more diverse group of students that came from all different areas, that were Black, that were African, and so I had so many other people that I could identify with, and so that started kind of building my own racial identity, and so I think that really formed the ability to identify as Black on my own terms.

And I think throughout time, just even gaining more knowledge individually about the Black experience in the United States and how it isn’t just one experience, but also kind of paying homage to the Black experience that I don’t have direct ties to just in terms of my immigrant experience with my family.

– Harry Kiiru: And I appreciate what you’re saying because part of, I think, you know, Black identity is that, is the ability to add on to it, so, you know, with the Caribbeans coming into the U.S. and, you know, what even reggae does to what we think of as Black popular culture.

And even now, say, with Afrobeats, like, you know, my sons are listening to Afrobeats in certain ways.

They may not necessarily think, “Oh, yes.

This is now part of contemporary Black culture,” but it is, and so there’s a way in which we are participating in its formation.

It’s not a closed box.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: However, you know, I think one of the things that you’re saying which makes it complicated for, you know, the immigrant is that we also don’t have the cultural memory and history.

And so there are ways in which, then, inasmuch as I would like to identify as Black, my own son was quick to remind me not that long ago.

He’s like, “No, Dad, you’re African.

You’re not Black,” and I’m like, so what does that mean, exactly?

– Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: They see me as, you know, racialized as Black, and so I think over time, for me, that category has become more political than anything, that I am politically Black because of my alignment with what it means to be Black, not just of the U.S., but of the world.

I have what I would consider home, Kenya, [chuckles] and where I am not racialized as Black in Kenya, and that, yes, if I am choosing to remain in the United States, if I am choosing to be here at this moment, that, yes, that I am Black.

At the same time, I am also considered African, so I was never African until I came to the U.S. because telling people, “Oh, I’m from Kenya,” they’re like, “What?”

you know, “Yes,” so I’m also African, but at the core, I guess, of maybe my, and I know we have intersectional thinking and all of that, at the core, I think, for me is that I am a Kikuyu man.

That’s my ethnic group.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Mm.

– Harry Kiiru: So because ethnicity and gender, you know, are primary to how we identify in Kenya.

And so part of the, my upbringing, the lessons that I have, the ways in which I see the world, the ways in which I parent, the ways in which I just function are rooted in being this Kikuyu man, and so, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

– Angela Fitzgerald: No, I appreciate how both of you described how you navigate both racial identity and ethnic identity within your presence in America and you, Naman, being Madisonian, you acknowledge you were raised here, so you’re like, “This is, Madison is home.”

And you, Harry, like, “I’ve been here for a while, “so, you know, I have come to maybe in some ways “become a part of the community and the culture here, but still, this is who I am.”

And depending on maybe the level of engagement you have with people, you can break that down for those who are curious and understanding, like I said, what are you, which, let me just pause there.

Is that a rude question?

Like, do you appreciate when people are inquisitive because they feel like, “There’s something different, “and I don’t quite know how to ask, but I want to know.”

Like, what is the best way that you appreciate people inquiring about your identity?

Or “Just don’t ask me and just leave me alone.”

Is that also an okay answer?

– Naman Siad: [laughs] – I think the way it’s asked, like, “What are you?”

I think, would send me off.

I think it just would, it wouldn’t be received well.

– Angela Fitzgerald: Mm-hmm.

– Naman Siad: I think, especially just wearing a hijab, you get questions all the time.

I remember my first semester here at UW-Madison, my lab partner just assumed that I didn’t speak English, and so he would just kind of gesture during lab and, like, speak really slowly and stuff and then eventually asked me, like, in a way, like, “What are you?”

Instead of just, “Oh, like, where are you from?”

– Angela: Right.

– Harry: Yeah.

– Naman Siad: And I think, even for me, I struggled because, obviously, I’m, like, tied to my Somali heritage through my parents, but if I went back to Somalia, or went to Somalia for the first time, I’d be labeled as American.

There’s really nothing about– My Somali is very broken.

I don’t have the lived experience of living there, and so I think I would get upset if people assumed that I wasn’t fluent in English because I think it’s the only identity that I really had because English was the language that I was most fluent in.

I was born and raised here.

Madison is where I grew up, and so that question, that othering used to bother me a lot more when I was younger, but then now I feel like if someone asks me in a respectful tone, I’m fine with it, but it is interesting because it does put you in a position where you’re othered, and if you haven’t become comfortable with being othered, it really does kind of take you out of feeling like you belong, especially if you’re a young child growing up in Madison and you’re the only person of color in your entire class and you’re trying to hold on to being just like everybody else.

I think that the older you get, you realize how identity is so much more complicated and intersectional than just what some, like, 10th grader thinks of you in your class.

– Harry Kiiru: For me, one of the issues, as you brought up around it is about the question, the questioning.

– Angela: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: One of my favorite places to visit is a monastery in Middleton, and I love this place ’cause it’s quiet and I could just… Having a day of solitude and silence, it just fills me up, and I remember being there not that long ago, and this person, of course, decided to rudely interrupt my quiet and peace by greeting me, and I said hi, and I talked a little bit, and he’s like, “Oh, yes, I noticed you have an accent.”

Which is fairly typical, and the next question is, “So where are you from?”

And for a while, you know, I would say things like, “Oh, I’m from Detroit,” or, “I’m from L.A., I’m from–” Like, “No, no, no, no, no, but where are you really from?”

And that question of where you’re from followed by, you know, this person ended up saying, “Your English is so good,” was fascinating to me because it’s not something that I’ve encountered once, twice.

It’s a very regular occurrence, and I think part of how, I’m gonna use a very big word that, you know, might throw off some people.

Part of, you know, being part of empire, so U.S. is empire, is not having to think of others in relation to you, you know, like, as empire.

You know, you don’t have to learn about anyone else.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry Kiiru: Everyone else gets to learn about empire.

And so the assumption, then, that my English has to be good does not take into account that, you know, Kenya was a former colony where we had to learn English so that we could be part of empire.

For the immigrant coming here, what is fascinating is to encounter people who claim to speak English, but their English is fascinating because it’s not textbook English, which is what we grew up with.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry Kiiru: So, yes, so someone would say, “Oh, your English is so good.”

Yes, because I say the word “yes” and not “yeah.”

– Angela: [laughs] – So your English is technically more accurate than native English speakers.

I hear you, I’m not disagreeing.

– Harry Kiiru: Much like going to the UK, where you discover oh, these former colonizers do not speak the English that they made us learn.

So language then becomes, you know, again, another way of othering where it is, you’re always reminded that you’re from somewhere else.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: That when you encounter empire in its fullness, that its job is to remind you that at some point, you have to go back to where you came from.

And so that this can never be home, no matter how long, and so it fascinates me.

I’ll meet people who have lived in the U.S., you know, for 30, 40, 50 years, and they’re always like, “Yeah, someday I’ll go back home to Ghana.”

“I’ll go back home to Nigeria.”

I’m like, “Wait, when are you going?”

[laughs] Yeah, so, yeah, so it is an interesting question in terms of what… And I don’t think there’s a good way to ask that question because what it’s trying to get after is difference.

– Angela: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: That you’re different, and, yeah, so, no matter how, you know, we want to sugarcoat it with our liberal logics and ideas.

It still gets at difference.

– Angela: Mm.

– Harry Kiiru: Yeah, yeah.

– Angela: Which, I think there’s a way people can ask or what’s driving the inquiry around difference.

I think you can pick up on if it’s coming from a place of, “I perceive you as not belonging here,” versus, like, a true curiosity, or “There might be a connection here, and I want to explore that further.”

And I say that because being physically within Madison, within the state of Wisconsin, the data suggests, right, shows that just lumping us all under the Black category, we are a small minority, relatively, within the state.

– Harry Kiiru: Mm-hmm.

– Naman Siad: Mm-hmm.

– Angela: Going to other states, other cities, that’s not the case, and so those questions wouldn’t necessarily emerge in the same way.

To me, it comes from a different place that feels like, “Oh, where, are we, is there a similarity, a connection here?”

Versus, “Wait a minute.

“You don’t look like how the rest of us look.

Where are you from?”

And granted, I don’t want to assume, right, the intent behind people’s questioning because maybe there is a genuine curiosity ’cause that’s just our human nature.

But I think there is something about the question that can come across as negative, and I appreciate you all sharing your experiences ’cause that can challenge those of us who ask those questions to think about where is that question coming from and how could it be framed differently so as not to be off-putting to the person that you’re asking said question to, so I appreciate that.

If we go back for a minute, what has that experience been like for you in terms of engaging with the community that the limited racial categories suggest that you are a part of, like navigating Black culture within L.A., within Madison, within Madison?

What has that been like?

And I do want to just add the disclaimer that I am defaulting to the term “Black” because I personally prefer that term over “African American.”

I mean, everyone has their preferences.

I know some people feel differently about “African American” versus “Black.”

Black, to me, just denotes a broader connection to the diaspora, doesn’t feel as limiting, so I like that.

And “African American” feels a little bit sanitized to me, so I kind of push up against that, but, again, to each his own, right?

But that’s just the term I choose to use, and however you all would like to use that terminology, feel free, but how have you navigated that space of connecting with the culture that others believe you are a part of just because of your skin tone?

– Harry Kiiru: I think it’s a good question.

You know, as I said early on, I think part of the challenge is recognizing that my cultural memory and history is much shorter in terms of being in the U.S.

So part of the reason for that, again, as I said, you know, in coming to grad school was to be able to understand myself better and my sons better and so, or to help them, again, you know, have the tools to navigate what it means for them to be Black because they’re born and raised in the U.S. And so Africa for them is only in relation to their dad, and whether they choose to pick it up or not, you know, that’s up to them.

But I remember, I was sharing early on, being in L.A., and I came across these two Black young men.

I had only been in L.A. for about a month, and I remember these two guys speaking.

They’re clearly talking to me, but I had no clue what they were saying.

And, you know, it went back and forth where I’m like, “Huh?”

I have no idea what is happening, and at some point, they’re like, “I guess you’re not understanding what is happening,” and so they walked away.

And there are ways I like to think of that moment as an invitation into Blackness, and at the same time, Blackness becomes taken away from me because I am not, I don’t understand what is happening.

And I think that moment comes to play out in different ways in my life living in the U.S. in that my immigration usually is always at the forefront of how I navigate my Blackness.

Yes, you know, I’ve learned a lot of, you know, Black history, what I am both thought of or someone is suggesting that I am or that I am part of a history and a genealogy, and at the same time for solidarity because, again, as I said, for me, I know where home is.

It is Kenya, and so my primary being in the U.S. is much more of an immigrant and a global Blackness in that sense.

And so solidarity, for me, then becomes very important in saying, I may not understand necessarily what your journey is like as a Black American because I am an immigrant.

At the same time, because I am racialized in the same ways that you are racialized, that I can stand in solidarity against, you know, white supremacy that seems to, you know, come down on us wherever it is that we’re coming from.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry Kiiru: In the same way that, you know, my Black American brother, sister cannot understand what it means to be an African immigrant because Africa within a Western consciousness will always be one of negation.

Africa will always be, you know, the place with, you know, the continent with, or even the country, as one American president said, [Angela laughs] the continent with, you know, wars, with famine, with disease, or exotic, you know.

It’s this place of, you know, animals, and so there’s absolutely no way for someone to understand this position of Africa much in the same way.

And one of the reasons why I do notice that a lot of African immigrants will end up being friends with other immigrants from other countries is because we do, there’s a way this, you know, migration allows us to be able to empathize and sympathize with each other.

We know what it means to be asked, you know, about how we speak, how we dress, the foods we make, those kinds of, or even the suggestion that, you know, we can go back to wherever we come from.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry Kiiru: So there’s a sort of a tension that then exists, and it’s a tension because it’s hard to unravel it.

– Angela: It is, and when you say that, I’m reflecting on experience I had in undergrad ’cause I had a very diverse friend group when I was in college, and so I went with some friends of mine to African Student Union meeting, Association meeting.

I’m like, “Okay, you know, here we go,” and so I remember, upon getting there, someone comes up to me and asks, like, “Where are you from?”

I’m like, “I’m from Maryland.”

They’re like, “Okay, well, where are your parents from?”

Like, “Oh, they’re from D.C.” And they just looked at me, was like, “Uh…” And, like, walked away like I was annoying them.

And I’m like, “I’m sorry, is that not–” I get it, though, I get it.

Like, in that sense, I was not the target demo, even though I was very eager to connect and to learn, but also feeling like, man, not welcomed in a space that I felt like could have been accessible to me, but that was a learning moment for me of, like, “Okay, “yes, phenotypically, there are some similarities here, but culturally, there are a lot of differences,” and just understanding that and navigating that will be to your benefit.

But, to your point of having a place to go home, I also wish I had that.

– Naman Siad: As much as I would love to say that if I took a flight to Somalia tomorrow, I would feel immediately at home, I know that that’s not the case because I haven’t experienced life there.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Naman Siad: But also knowing that that is still an option for me just because of my family and my history with just my ancestors being from Somalia.

And I think growing up in Madison is different than coming to college here.

I think growing up, I had a pretty diverse high school, like, I think, as diverse as it can be in Madison.

But I think coming to campus was the biggest shock for me because I was now one student of 300 that was any sort of, like, ethnic, like, any sort of person of color in my, like, chemistry lecture, for example.

I think I clung to my Muslim identity very tightly in college because that was the identity that I was most comfortable with.

– Harry: Mm.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Naman: But it turned into kind of the same in that a lot of the friends that I had were friends from different immigrant communities but that weren’t necessarily Black, and I think, especially being a dark-skinned woman, there’s very few chances of feeling empowered in terms of feeling comfortable in your skin, in terms of feeling empowered as a dark-skinned Black woman, and so I remember still struggling in college.

Even though I was surrounded by Muslim students, I still remember feeling insecure with my skin color and not feeling comfortable in my own skin.

And I think when I went to law school, I was a part of the Black Law Students Association, and all five of us were– [all laugh] There was a very small community, but… – Small but mighty, okay.

– Naman: I think I remember that being one, and in college as well, with the different programs I was with just learning about Black history in the United States from friends, from classes that I took, and kind of just unpacking the very white-centered narrative that you learn in public school and finding empowerment in Black history.

And also understanding that, as a second-generation immigrant, I owe it to myself to learn that history because if it wasn’t for that history, my parents or other Somali immigrants or other African immigrants wouldn’t have been able to come to the United States.

And so understanding that, I think, finding empowerment in that history really shaped my relationship with the Black community and understanding that, even if I am in the periphery, I find a lot of empowerment in it, and so I think that really shaped my understanding and made me realize that it is white supremacy that separates us and doesn’t allow for there to be nuance in our identities.

It’s you’re either Black or you’re not or you’re African or you’re not, and it’s so much more complicated and rich and messy than that, and I think growing up, I was always trying to find one box that fit my identity completely, and there wasn’t that opportunity.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Naman: But I think now that I’m older and also just having a global context, like, living in London, I realized how Blackness is viewed a very specific way in the United States, but once you get out of that bubble, you realize that Blackness is much more diverse globally and how there’s so many different types of Black communities, and just understanding that racial contexts are different and that it’s not, I think the American racial context is very specific, and sometimes we can, at least for me, tend to project that onto other communities when, in reality, each country and each community has its own history and relationship with race, ’cause it’s socially constructed at the end of the day.

– Angela: Absolutely.

– Naman: And I think that’s the trouble that a lot of– I always have this conversation with my parents.

That’s the trouble that happens when you come to this country because in Somalia, there’s not any, like, racial backgrounds.

Like, there’s different tribal groups.

There’s different languages, but people don’t identify as white or Black.

They identify by their tribe.

They identify the region that they’re from, the village that they’re from, and so it’s that specific.

So when you come here and they’re like, “Oh, you’re Black,” they’ll stare at you like you’re crazy.

They’ll just be like, “I’m not, I’m from this village, this is my tribe.”

But then you become racialized through living here, and so…

– Angela: That understanding helps to diminish some of the tension that could arise from the perception that there’s a rejection of Blackness.

– Harry: Mm-hmm.

– Naman: Mm-hmm.

– Angela: Right, because you’re right, when you come here and you look a certain way, a label is applied to you, and for someone to say, “Nuh-uh.”

I think, from a Black American standpoint, it could look like, “Well, wait a minute.

“So you’re trying to say you’re not one of us?

Here, you’re one of us.”

– Naman: Mm-hmm.

– Angela: And then the person in question might be like, “No,” so I think it also goes back to an earlier point you shared about what is shared liberation or shared contributions towards the outcome that we all want to see, given certain similar lived experiences we might have here, what does that look like?

But I want to put a pin in that for a second ’cause you also said a term that I want to get you all’s opinion on how you feel about it.

You said you were at UW-Madison.

You referred to, I think, you and maybe your social group as people of color.

– Naman: Mm-hmm.

– Angela: How do you all like that term?

Do you gravitate towards it?

Do you feel like that’s a lazy term that’s just used in majority-white spaces?

‘Cause, honestly, that was a term I don’t think I really heard people even use until I moved to Wisconsin.

– Naman: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: I think, you know, one of the challenges, of course, is that race as a meaning-making mechanism always has to do this, like, double work of rejecting, you know, oppression and at the same time trying to consolidate.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry: So, and it truly is a double-edged sword, so because if you are now racialized as Black and part of a group that is, you know, BIPOC or whatever iteration it is that is in relation to oppression, but you don’t even– That oppression is not the same across the board.

That there are ways that it is still doing the same kind of, you know, politic work that oppresses it in the first place, if that makes any sense.

So it is, in a sense, you know, unique, as you were getting at, in terms of how things function in the U.S., but there’s always been language, as, I think, we were talking earlier on, about language of liberation.

There’s always been ways of thinking about, okay, how do we collaborate, how do we work together, how do we…

But, unfortunately, sometimes these sorts of languages do.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry: They, yeah, don’t work the same way, so I honestly don’t think I’ve ever used that term to refer to people in that sense.

Much like I am implicated into the category of Blackness, I am also implicated into, you know, people of color, and I can see its utility.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: And maybe this is just the academic side, you know, which is always trying to interrogate the end nuance, while maybe that’s not even, I mean, it’s not necessary, so yeah.

– Angela: Mm, okay.

– Naman: I’m trying to think why I use that term.

I think it is navigating, like, a campus like UW-Madison and just the language that is used to group students together.

I think I just became used to saying that because it would usually be used in reference to finding solidarity with other students in your class.

But when I do think about it, it is a double-edged sword because on one hand, I do find a lot of solidarity and empowerment in other communities and realizing that a lot of the struggles are directly intertwined and the separation kind of puts lines in between that, and then it turns into this community fighting for its own liberation, this community fighting for its own liberation.

And so maybe it was an attempt at kind of bridging, but then it does turn into kind of lumping all of those struggles together and understanding that each community has its own unique experiences and that I think you can even see it in, like, the racial politics today, where we’re being bombarded from all different directions, but there are different needs and also experiences that people have.

And so I do think it was a term that I picked up going to UW-Madison, though, just–

– Angela: And that’s fine.

I didn’t want to, like, pick on you for using it.

I just heard it, and I was like, “Hmm, I wonder how she feels about that,” so I appreciate you indulging my question.

Because, unfortunately, at times, there is this divide, Africans versus African Americans or Black Americans, the two not being in alignment, even though they may look like the same person, but not being necessarily on the same page about things.

But then certain aspects of the outside world looking at the group, seeing, like, “Y’all look all the same.”

So how do you personally navigate that?

What are your recommendations on how we can improve that?

What might we all need to learn or understand better to move things forward?

– Naman: I think your sons’ experiences are kind of mirrored in my own experiences, and just hearing it from your perspective, I think, also made me realize what my parents also went through when it came to their own racialization ’cause I think, for me, it was, and for my siblings– I have a sister and two brothers– I think for the four of us, it felt natural to kind of start picking up things from Black history and Black culture and identifying, especially when we had kind of a void of Somali culture because we didn’t grow up around a lot of Somalis.

And I think it would be very different if we grew up in, for example, Minnesota, where there’s a very large Somali diasporic community.

And so there was always that tension growing up between what we identify as and what my parents view their own identity as, and it’s interesting ’cause I think they also have been on their own journey.

I think when they were raising us, they had kind of, not a rejection, but I think they tended to gravitate more towards other immigrant communities, especially within the Muslim community, because they were trying to hold on to making sure that part of our identity was still connected.

But, and I always had, I remember having conversations with them or with relatives that would sometimes say things that were kind of problematic when it came to the Black community ’cause they had very…

There was, like, an othering and trying to explain that, for example, my relatives’ sons are gonna be racialized by the police the exact same way as a Black American family would be.

And so I think that the separation, I think, comes from coming to terms with your own identity and navigating the space and understanding that it’s gonna be different.

I think it’s different for me versus my brothers.

I think my hijab adds a very complicated layer to all of it, and so I think my brothers may be able to be racialized as Black a lot easier than me, for example, but then my parents would have a completely different experience as Somali immigrants.

I think in a roundabout way, I think it’s, it’s complicated, I don’t know.

– Angela: But, no, even as you say that, thinking about like, yes, there are these divisions and those divisions are intentional because on both sides, the messaging that’s been communicated about our respective groups through media has largely been negative.

I mean, I think there’s a pushback against that, and we have more exposure to independent artistry, so I think we’re getting more authenticity than maybe prior generations.

But there were negative narratives on both sides of what Black Americans look like that was portrayed to the rest of the world, and when the rest of the world comes here, then there’s an idea already implanted about what Black Americans is, what Black Americans are like, and then, conversely, like you said, Africa as a country, and, you know, the jungle and all these things, that being pumped the other direction, and then you get the ignorant questions from people who they think that’s real and then are bringing, again, ignorance to your doorstep.

So how we push back against both?

Because both are rooted in, like you said, white supremacy, racism, colonialism.

– Harry: Yeah.

– Angela: And, again, intended to divide, but go ahead.

– Harry: Yeah, no, and you’re right in that the messaging then becomes a starting point of understanding the other.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry: And so when we do not have a relationship with the other, then it’s just whatever the stereotypes, whatever the playbook is that you’re on.

And so growing up watching, you know, Fresh Prince or Family Matters, so there’s a way that I get to understand this is what the U.S. is like.

This is what Black culture in the U.S. is like, and I land in L.A., and I’m like, “Wait, no, what is happening?”

So there’s that dissonance that then comes to exist.

At the same time, we do have to remember that a large number of African immigrants who come to the U.S. are highly educated.

They’re coming here either for school, so the health outcomes are much higher than even, you know, white Americans, education levels, and, you know, even wealth and social networks type thing.

And so these are not the representative of the collective.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: And so the issue, and then, you know, there are different scholars who’ve written a lot about this.

But the issue becomes that this group who come here in that regard cannot also be compared with every Black American because, you know, of what, you know, they’re bringing with them.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: And so the challenge, then, with this category of people is, of course they’re going to reject Blackness because, you know, they’re like, “Wait, I have, “from where I’m coming from, I’m very educated.

“I don’t understand why I need to be given a category that is inferior,” because, again, Blackness is not, or any racial category, they are not neutral categories.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry: It isn’t just saying, “This is a chair.

This is a cup,” but that there are meanings that are imbued within these categories, and so saying that I am Black also implies that I am inferior to someone.

It also implies that I am incapable to, you know, a white subject, and so of course then the rejection has to be there.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: So the challenge, then, and I think this is one of the pieces that, you know, Black-racialized African immigrants don’t also understand is that if it was not, say, for civil rights, we wouldn’t be here.

– Angela: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

– Harry: [Harry chuckles] – Yes, I mean, the floodgates don’t get opened ’til the ’60s to now allow, you know, regular, non-elite Africans to come to the U.S., and so when you ask them the question of what does it mean maybe going forward, I think…

So, as I said, one of the groups that I study, they’re called the Airlifters.

They came to the U.S., about 800 of them, from East Africa, and they were nation builders.

So a visionary man, you know, was like, “Okay, we need to figure out “how do we get all these, you know, Africans to the U.S. “for education because the British “are not giving us adequate education “and at some point, we’re going to gain independence, and so if we’re going to govern ourselves”– his name was Tom Mboya– “we need to be able to do that.”

So what ends up being fascinating is that the people that Tom Mboya ends up partnering with in the U.S.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: Whether it’s, you know, people like Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Malcolm X, MLK, that they end up building these networks of solidarity because for each group, they need each other.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry: Yes, so fighting for civil rights and fighting for African independence.

And so there’s a way, then, it was so much easier, not just even so much easier, it necessitated that sort of solidarity in order to, you know, for each group to gain, you know, their independence and civil rights.

So I don’t know if there’s a moment or a thing that sort of brings us together now, not even, even Black Lives Matter, as I was saying earlier on, it might attempt to do that sort of work, but it doesn’t.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: I think our second generation’s people are the future in that sense.

Like, the kinds of things I even look at my own sons, the kinds of questions they are asking, the kinds of ways they are both troubling what it means to be Black and also, you know, adding to what it means to be Black, is fascinating.

– Angela: Right.

– Harry: Yeah, so there’s hope in that way.

– Angela: There’s dangers in lumping because, “A,” lumping just completely minimizes difference in ways that we maybe aren’t attending to needs because the needs are getting distorted when vastly different groups are just put together.

Those are conversations I hear happening in educational institutions all the time.

You put all Black students together, you have African students.

You have Black American students.

You distort the needs, same with Asian students, right?

Like, which part of Asia are you from?

That may inform how best you could benefit from different types of support, so let’s not lump, but how do we come together, to use your word, reach a place of solidarity where we recognize there are certain shared experiences in the United States that we might have, and how can we support one another in working through whatever shared liberation looks like for us while we’re here.

And acknowledging you have a place to go to home, so you’re like, “I might be here temporarily, but while I’m here…” What might your liberation look like, and, as you mentioned, what might be the nuance, even for second-gen individuals in terms of their understanding of race and ethnicity and how that helps us to further move this conversation forward?

So I appreciate both of yours perspective on that, and is there anything that we have not touched on today that you want to make sure that we talked about?

Anything related to your background or your work or anything you want our audience to know before we close?

– Naman: I think one thing that kind of builds on the international global solidarity, I think, especially in the political climate that we live in right now, we’re… And I feel like historically, we have also not been this connected to each other internationally and seeing how the struggles that we may face here in the United States are very similar in different countries and not kind of diminishing the differences, but understanding that American empire is all over the world, and I think that’s one thing that I’ve been thinking about a lot.

I think within the American context, American empire tends to focus on America and exceptionalize the American experience without realizing that things here affect globally.

And so I think, whether it’s police brutality, brutality within immigration, genocides across the world, I think you start to see the threads across the world when you focus in on those similarities, so.

– Harry: And I appreciate that ’cause the…

I just got back from Kenya, and one of the things that I’ll hear from a lot of Kenyans is, “Oh, I want to go to the U.S.

I just really, is there a way…” In fact, someone sent me a text and is like, “Oh, you know, I know how to drive a car.

“I have a driver’s license.

Can I come and work in the U.S.?”

I was trying to explain to him how hard it is to come to the U.S. from the continent.

Up until very recently, you really– It’s nearly impossible even just to apply for a visa.

You know, you can’t just go and get, you know, a student visa or a visitor’s visa or even a working, you know, sort of visa to come to the U.S.

These challenges, then, of migration, it means that those of us who end up coming here, in many ways, we’re quite fortunate.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: But at the same time, encounter empire in ways where you’re like, “Huh.”

I don’t, you know, it’s like seeing how the sausage is made where you, there are ways that becoming or this process of becoming Black starts to put undue pressures on you in ways that you never had encountered.

There’s a scholar I just was reading recently who was arguing that the longer African immigrants reside in the U.S., the worse their outcomes get.

And so we may have come with better health, wealth, and educational achievement outcomes, but staying longer in the U.S., our outcomes get worse.

– Angela: Does that mean that they become more Black in that sense?

– Harry: There you go.

– Angela: That’s unfortunate.

– Harry: And so when I’m listening to this person saying, “I really want to come,” and I’m thinking, “Okay.

“I’ve been here for almost 30 years, “and my doctor’s already telling me about things about my body, and I’m like, ‘Wait, what’s happening?'”

and so that that these categories, there’s something that is happening on the African continent now.

– Angela: Mm-hmm.

– Harry: That is unique, that is beautiful, that’s whole, that is, yeah.

– Angela: Stay tuned.

– Harry: Stay tuned.

– Angela: – Thank you both so much.

I appreciate your time tonight.

– Harry: Yeah, yeah, thank you.

– Naman: Thank you.

– Angela: “Black,” “African American,” these words carry more than definitions.

They hold stories, history, and the power of identity.

Tonight, we’ve explored what they mean and why they matter, but the conversation doesn’t end here.

It’s a journey of understanding, growth, and connection because identity is more than labels.

It can be a bridge to who we truly are.

Watch additional episodes and content at WhyRaceMatters.org.

Thanks for listening to the Why Race Matters podcast. If you like listening to the show, please rate and review us on Apple Podcasts or your podcast app of choice…it helps people find the show. For more conversations from PBSWisconsin, please visit at WhyRaceMatters.org.

[bright music] – Announcer: Funding for Why Race Matters is provided by Park Bank, UnityPoint Health Meriter, UW Health, donors to the Focus Fund for Wisconsin Programs, and Friends of PBS Wisconsin.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us