Why the Impact of Wisconsin's February Wolf Hunt Is So Uncertain

Holding the hunt after alpha wolves have paired up is a recipe for unpredictability.

By Will Cushman

February 23, 2021

A yearling female gray wolf is on alert in this April 2014 trail camera image from the southern Lake Superior region.

Following a court order, Wisconsin’s growing number of gray wolves are back in hunters’ sights in 2021 for the first time in more than six years. But exactly how Wisconsin’s first regulated wolf hunt since 2014 will affect the state’s wolf population is a guessing game for wildlife specialists.

The hastily-planned hunt began on Feb. 22 and was set to wrap up just two days later as state-licensed hunters and trappers quickly approached a harvest limit of 119 wolves set by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

The DNR previously intended to wait until fall 2021 to open the state’s first regulated wolf season since the former Trump administration removed federal protections for gray wolves in the Lower 48 U.S. states. Those protections officially ended on Jan. 4, 2021, when the gray wolf was delisted from the Endangered Species Act.

But the DNR’s plan was upended after a Kansas-based hunter organization filed a lawsuit in Jefferson County claiming the DNR was not following a state law that mandates an annual wolf hunt between November and February when the wolf is not subject to federal protections. The court agreed and on Feb. 11 ordered the DNR to hold a hunt before the end of the month.

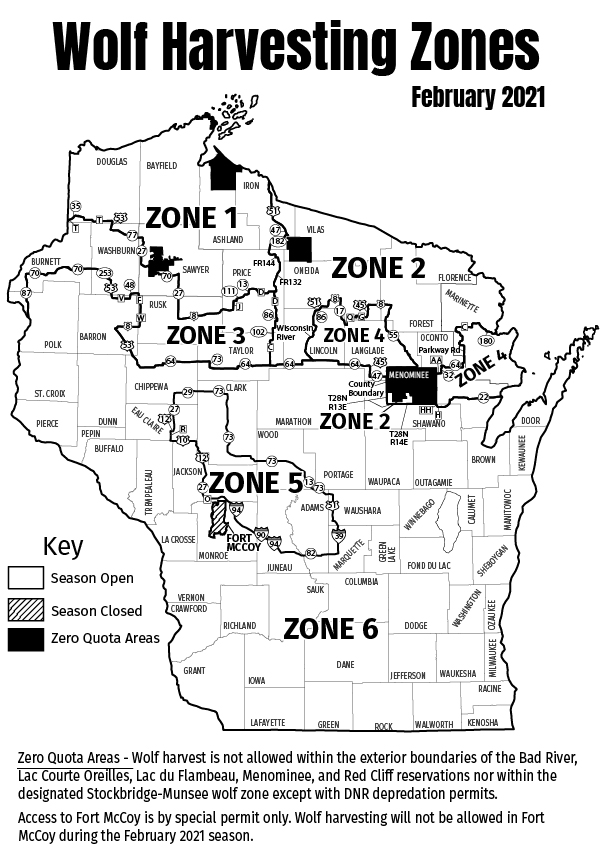

The total harvest quota of 200 — including 119 wolves allocated to state-licensed hunters and trappers and 81 allocated for harvest by tribal communities in the Ceded Territory — is intended to keep Wisconsin’s population of roughly 1,200 wolves more or less unchanged, according to the DNR. It includes precise targets for each of the state’s six wolf management zones.

Map of wolf harvesting zones in Wisconsin. (Courtesy: Wis. Dept. of Natural Resources)

“We determined the harvest objective was to hold the population stable using the best available information, biological and social,” said Keith Warnke, administrator of the DNR’s Division of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, at a Feb. 15 meeting of the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board.

Warnke told the board that department staff arrived at the quota after considering a number of factors. These included the most recent wolf population estimate, the effect of previous hunting seasons on wolf numbers, Wisconsin’s current wolf management plan last updated in 1999, scientific literature, and model projections that estimate the impacts of various harvest quotas.

While Warnke detailed the scientific basis for the harvest quota, he acknowledged that the abbreviated timeline meant the public did not have a meaningful chance to weigh in. In an email to PBS Wisconsin, DNR spokesperson Sarah Hoye said agency biologists, research scientists and a representative from the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission representing the six Ojibwe tribes in the state met to develop harvest quotas.

A 2019 wolf relationship plan published by the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa criticized recent wolf hunts held in the Lake Superior basin for failing to incorporate traditional ecological knowledge of gray wolves — known as Ma’iingan in Ojibwe — into the process of setting harvest quotas.

Messages left for the Bad River Band’s wildlife specialist, who co-authored the 2019 plan, were not returned.

Hoye provided more detail about the scientific research informing the February 2021 harvest quota. She pointed to two peer-reviewed papers that evaluated “many studies of North American wolf populations to estimate and define how wolf populations respond to human-caused mortality, including regulated harvest.”

One paper, from 2008, assessed population dynamics of wolf packs in Alaska, while the other, published in 2003, looked at wolf populations over a larger scale.

Still, wildlife specialists in Wisconsin say it is next to impossible to forecast exactly what impact the February hunt will have on Wisconsin’s wolf population. That is in large part due to the timing of the hunt, which is unprecedented in Wisconsin’s history of regulated wolf seasons.

“When you start a harvest in the middle of winter, there are a lot of unknowns,” said Adrian Wydeven, a former wolf biologist for the DNR who led Wisconsin’s wolf program from 1990-2013 and retired from the agency in 2015.

Wydeven pointed out that wolf hunts held in Wisconsin between 2012-2014 occurred in late fall and early winter. Applying results from those seasons to a February hunt is not a clean comparison, he said.

For starters, the February season overlaps with a critical period in gray wolves’ annual biological and social rhythms. Wolves are highly social animals that typically live in packs structured around an alpha male and female. The alpha pair are a pack’s only breeding members, and Wisconsin’s wolves breed in January and February.

“Growth in the wolf population is highly dependent on the alpha pair,” said Tim Van Deelen, a large mammal population biologist and professor of forest and wildlife ecology at UW-Madison.

Van Deelen said any alpha females killed in late February are likely to already be pregnant.

“If you remove a pregnancy from a wolf pack, then you lose reproduction for that given year for the entire wolf pack,” Van Deelen said.

Additionally, Van Deelen said killing one or both members of a pack’s alpha pair after they’ve bred can potentially upend a pack’s social structure.

“The pack itself might be broken up,” he said.

On the other hand, if an alpha wolf is killed in late fall or early winter, there is time for a new alpha pair to form and breed. That’s a less likely scenario if one or both alphas in a pack are killed in late February.

Van Deelen contributed to a 2015 study that modeled the potential impact of different harvest scenarios on Wisconsin’s wolves, including differences in the timing of the hunt. The study modeled what might happen if 25% of the wolves harvested during Wisconsin’s 2012 hunt were killed later in the season, after breeding was already underway. It forecasted a long-term reduction in population growth under that scenario compared to a hunt held entirely before breeding.

“There’s a pretty dramatic difference in the growth trajectory just by changing the timing,” Van Deelen said.

At the same time, there is no way to know how many pregnant females, or alpha wolves in general, might be killed during the February 2021 season.

“The thing that the DNR is really struggling with here is that there’s all these sources of uncertainty that they don’t have any control over,” Van Deelen said.

Another source of uncertainty is the accuracy of the DNR’s current population estimate of roughly 1,200 Wisconsin wolves. That figure is based on the DNR’s last winter wolf count, which occurred between January and March 2020. Van Deelen said he believes the annual count, which employs hundreds of volunteers and DNR staff, is fairly accurate and likely within 10-15% of the population’s true number.

Jeremy St. Arnold, a wildlife biologist for the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, identifies wolf tracks in the snow while surveying for the animals. Wisconsin’s annual wolf population estimate is derived from winter surveys when the population is believed to be at its lowest point of the year and when snow and a lack of foliage make it easier to track the animals.

But the true number of wolves in Wisconsin diverges from the annual estimate over the course of the year as pups are born and wolves die from any number of natural or human causes, including vehicle collisions, targeted killing of problem wolves that harm livestock and illegal poaching.

“We have an ongoing harvest all the time in that wolves get illegally killed,” said Wydeven. Illegal poaching typically removes around 10% of the state’s wolf population every year, he said.

“And typically the highest rate of illegal killing occurs during the fall hunting seasons” for other species, Wydeven said.

Since poaching deaths usually go unreported, it’s impossible to know how many wolves were removed from the Wisconsin landscape since March 2020. Either way, the discrepancy is bound to be significantly larger in February than it would have been in November.

Even so, Wydeven said the DNR’s harvest quota of 200 is within a range that would ensure the population’s long-term stability. However, with the 2021 winter wolf count already underway, the timing of the February hunt will surely impact the new count’s accuracy, Wydeven said. That is one more element of uncertainty the DNR will contend with as it updates the state’s long-term wolf management plan and sets a harvest quota for the next wolf hunt.

Additionally, a population of 1,200 wolves, while nearly four times higher than the state’s target population under its current management plan, is small enough that differences in timing and other factors surrounding the February hunt could have a significant impact on Wisconsin’s wolves for years to come.

“This is a very small population, and the small population sort of amplifies the uncertainties,” Van Deelen said. “So it’s really difficult to predict. The population could grow next year … or [wolves] could decline by as much as 20%.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us