Wisconsin's Modest, Uneven Population Growth So Far In The 2010s

It's a time of profound change for Wisconsin's population — where it's concentrated, where it's moving, which age groups and racial and ethnic origins it reflects, and what kinds of lives all residents are seeking to live.

By Scott Gordon

June 5, 2018

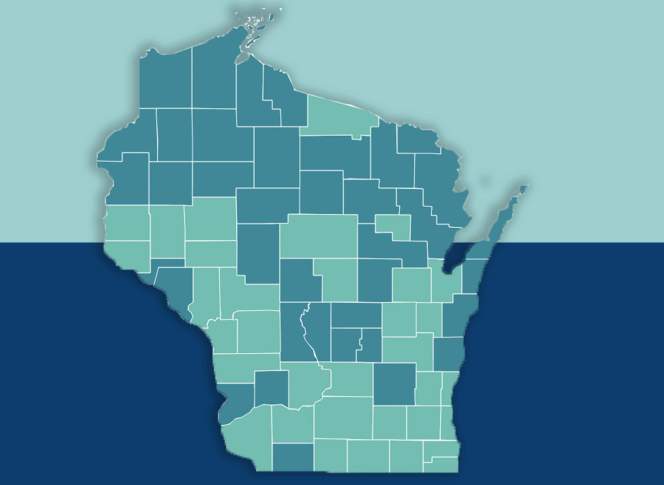

Wisconsin population trends in 2010-17 map and illustration

It’s a time of profound change for Wisconsin’s population — where it’s concentrated, where it’s moving, which age groups and racial and ethnic origins it reflects, and what kinds of lives all residents are seeking to live. Demographers project that over the next several decades, Wisconsinites will be increasingly concentrated in urban areas and less dense nearby places, while the state’s most rural regions become more sparse and their populations age. These transitions are already in motion, and figures the U.S. Census Bureau released in December 2017 reflect just how much can change in just seven years.

This particular dataset, titled “Estimates of the Components of Resident Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017,” shows Wisconsin as a whole gaining 108,195 residents during that time span, an increase of about 1.9 percent. But what’s far more revealing is how the patterns of population change — births, deaths, migration in and out — break down around different parts of the state.

Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now addressed some of the Census highlights in a June 1, 2018 segment.

So far in the 2010s, the projected population decrease in rural Wisconsin is indeed happening. Adams, Ashland, Iron and Rusk counties all lost four percent or more of their population between April 2010 and July 2017. Except for Iron County, each sustained the demographic one-two punch of deaths outpacing births and more people moving out of the county than into it. Iron County had 245 more deaths than births, which was offset a bit by a net positive number of 93 people moving in over the seven-year span. Adams County experienced a dramatic disparity between births (954) and deaths (1,824) whereas most of Ashland and Rusk counties’ population loss is due to people moving away. Each of these four rural counties experienced a different balance of factors, which in turns indicates slightly different stories — social, economic, and otherwise — within a broader trend of rural population loss.

The state’s two most populous counties, while still growing, saw very different shifts. Dane County gained 48,341 residents in the seven year period, with 26,370 more people moving in than moving out. Over that same time, Milwaukee County gained 4,349 residents. One reason that increase is so modest is that the county experienced a negative “net migration” — subtract people moving out from people moving in, and the resulting number is -37,409.

Meanwhile, Waukesha County, Wisconsin’s third most populous, saw a population increase of 10,685, with respectable gains from both births exceeding deaths — “natural increase,” in the parlance of demography — and people moving into the county. The biggest population loss in sheer numbers was Manitowoc County, whose population dropped by 2,267 between April 2010 and July 2017. That’s about a 2.8 percent drop, not insignificant but not as large a portion of the county’s population as it was in some of Wisconsin’s more rural counties; Manitowoc County still has nearly 80,000 residents.

A single year of U.S. Census data covering July 1, 2016 to July 1, 2017, offers a shorter-term comparison. Over that time, Wisconsin’s population growth was also modest, in keeping with the longer-term trend.

One difference between the seven-year (2010-17) comparison and the overlapping one-year (2016-17) numbers is that the former shows the state as a whole experiencing negative total migration, while the latter shows more people moving into the state than out. Additionally, areas that have taken a hit over the course of the decade — and perhaps seen population loss amid the fallout of the Great Recession — showed some short-term gains.

For instance, Sheboygan County saw a net loss of 166 residents between 2010 and 2017, but between 2016 and 2017 its population actually grew by 227. David Egan-Robertson, a demographer with the University of Wisconsin Applied Population Lab, pointed out to Wisconsin Public Radio in March 2018 that such numbers could indicate a bit of healthy pickup for manufacturing, which is a big part of Sheboygan County’s economy.

In some senses the numbers for 2016-17 are a bit more promising than the long-term ones for the seven-year span starting in 2010, but evidence remains of a profound long-term shift in rural Wisconsin’s population.

Editor’s note: This item is corrected to reflect that Milwaukee County experienced negative “net migration” between 2010 and 2017.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us