Wisconsin's Lead Water Pipes Are Often Buried With History

The state of Wisconsin is getting ready to parcel out $14.5 million to help communities replace thousands of lead service lines. However, short of digging up every single pipe in a community or surveying every property owner, there's no way to know for sure where all the lead is located.

October 4, 2016

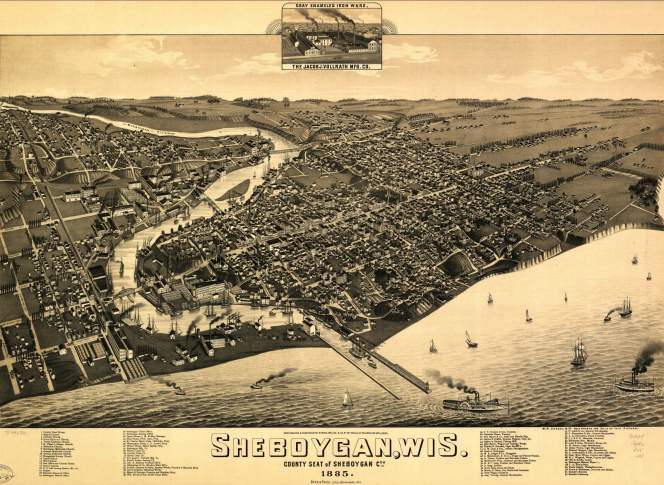

1885 Sheboygan pictorial map

The state of Wisconsin is getting ready to parcel out $14.5 million to help communities replace thousands of lead service lines. These are the pipes that run from a utility’s water main to individual homes and businesses, and are a primary source of lead in drinking water, along with solder and faucet fixtures containing lead. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources has announced that it plans to award funding to all 38 municipalities who have applied for it so far.

Congress prohibited the installation of new lead water pipes in 1986 due to the metal’s health effects on people who consume it, particularly children. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Lead and Copper Rule requires water utilities to regularly monitor for lead (among many other contaminants) and to improve their water treatment practices if they detect high levels.

These changes didn’t mean water utilities and property owners immediately dug up and replaced pre-existing lead pipes — millions remain in use, based on an analysis by the American Water Works Association. Many municipal governments have taken an incremental approach, replacing lead pipes when they’re already digging up an area for road construction or other projects. A very few U.S. cities, including Madison, ambitiously set out to replace all lead pipes connected to their utility’s system — these efforts took many years because of the work and expense involved.

Further complicating this issue is that a service line generally has two sections — one belonging to the utility and the other belonging to the property owner. Some local governments might collect records from their utilities and/or private plumbers, and of course it’s logical to deduce that buildings and pipe infrastructure built before 1986 are more likely to have lead pipes. Individual home and property owners can use a few simple methods to figure out if they have lead pipes in place.

However, short of digging up every single pipe in a community or surveying every property owner, there’s no way to know for sure where all the lead is located. There is no uniform approach to tracking the location and number of lead pipes, and estimates of the total number in place around the United States is in the millions. This lack of information has consequences: Not only does it make it harder to identify lead service lines for replacement, but it also makes it tough for municipal officials to target their monitoring efforts on homes that might be more vulnerable to lead contamination.

Knowledge gaps in Wisconsin

Of the 38 municipalities looking for funding from the DNR, 10 are completely absent from EPA data estimating the number and locations of lead pipes in Wisconsin: Bayfield, Florence, Menasha, Oshkosh, Rhinelander, St. Francis, Sheboygan, Stratford, West Milwaukee and Wisconsin Rapids.

Miguel del Toral, a regulations manager at EPA’s Chicago office, spent five years on the report and realizes that it is incomplete, as the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism reported in February 2016. He based these estimates on annual reports water utilities submitted to Wisconsin’s Public Service Commission in 2013. The EPA announced in February 2016 that it wants to work with utilities to get more information about lead pipes online, but it’s not clear how long this will take.

The Lead and Copper Rule does require utilities to keep inventories of the materials they’re using, but this requirement clearly hasn’t translated into comprehensive or easily accessible information. Utilities are supposed to use their materials inventory to find specific homes with water that would be appropriate to monitor for potential lead problems. The EPA itself, however, doesn’t collect or track data from individual municipal inventories.

“Please note that we have not verified the information contained in [water utilities’ annual] reports, and utility records are often incomplete and can also contain errors,” EPA spokesperson Anne Rowan said in September 2016, referring to the information del Toral’s 2013 estimate relied upon.

“Also keep in mind that although the service connection materials are reported, we have no information on what the service connections are for,” she added, “and in some cases, due to the large sizes of the [lead service lines] listed, it may be possible that some of these larger size service connections are used for reasons other than to supply potable water for human consumption.”

Surprises and index cards

Robin Schmidt, who heads up the DNR’s loan program, said she’s not surprised that the EPA’s tally has some blind spots.

“Sometimes municipalities tell me that it’s a surprise when they’re doing repairs when they find some of these [lead service lines],” she said.

The city of Sheboygan likely has about 6,000 lead service lines still in use, said Sheboygan Water Utility superintendent Joe Trueblood.

“The installation of those water laterals occurred long ago, and mostly the information resides in an index card a plumber filled out the day they put it in,” he said. “I don’t think those records were ever digitized.”

Trueblood said the city hopes to use $335,000 from the DNR program to replace lead service lines in about 65 homes along Broadway Avenue, on the city’s northwest side.

Sheboygan’s 2015 annual report to the PSC doesn’t mention those 6,000 pipes. In a rare anomaly, Sheboygan treats the entirety of each service line as private property, and its PSC report only asks for information about utility-owned pipes. The city also has a pretty clean record where lead contamination is concerned.

“We don’t have corrosive water, we don’t have lead test results indicating a problem,” Trueblood said, referencing a fairly common chemical reaction that can occur in drinking water pipes. DNR water records back this up — Sheboygan’s water utility hasn’t had a sample exceeding the EPA’s lead action level since 2002.

“However, we want to start making progress replacing these as early as we can,” Trueblood added. “The money is a helpful start. It isn’t nearly enough to continue. But it’s a good start.”

That last statement is a common refrain among water officials around the state. Even Schmidt has acknowledged that the DNR program’s $14.5 million budget only puts a dent in the problem. The EPA estimate alone found about 176,00 lead service lines in Wisconsin, and replacing them all would cost more than a billion dollars.

Focusing on private water pipes

Another community not mentioned in the EPA estimate is the village of West Milwaukee. However, this is likely because the community relies on the Milwaukee Water Works. The EPA does account for the city of Milwaukee’s water utility, which has tens of thousands more lead service lines than any other place in the state.

West Milwaukee village engineer Len Roecker estimates the village has about 1,100 lead service lines. He’s planning to use $130,000 from the DNR program to replace pipes in some homes along South 46th Street. This will be the first time West Milwaukee has eliminated any lead components from its water system, and Roecker hopes it will “kickstart” a more comprehensive effort.

“I think everybody in the engineering world understands that many of these service lines are at or above 100 years of age, and either way these assets need to be replaced,” her said.

The DNR loan program is deliberately earmarked for replacing the private portions of lead service lines. It can be difficult to convince homeowners to take on the cost of replacing their service line — which can cost $3,000 or more — and utilities cannot use money from customers’ water bills to replace pipes on private property. Under the DNR program, a utility can take on the entire cost of replacing a homeowner’s service line, or come up with an agreement to split the cost.

“Nobody knows how many private-side lead lines there are,” Schmidt said. “We know that municipalities have been replacing their side of the service lines, and individual homeowners have not been.”

Asked whether the DNR had any plans to do additional tracking of lead service lines in Wisconsin, she replied, “We don’t have a source of funding for doing that sort of study.”

“The water utilities on their own might want to do some surveying of their customers,” Schmidt noted, but added she is not aware of any utility taking on such an effort.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us