Wisconsin's 'Comparatively Unimpressive' Jobs Recovery

More jobs does not always mean greater opportunities for people of different genders, races, or geographic areas.And a broad economic recovery does not necessarily offer a steady outlook for job-seekers.

September 12, 2016

Crop of COWS map showing 2015 county unemployment rates in Wisconsin

More jobs does not always mean greater opportunities for people of different genders, races, or geographic areas. And a broad economic recovery does not necessarily offer a steady outlook for job-seekers.

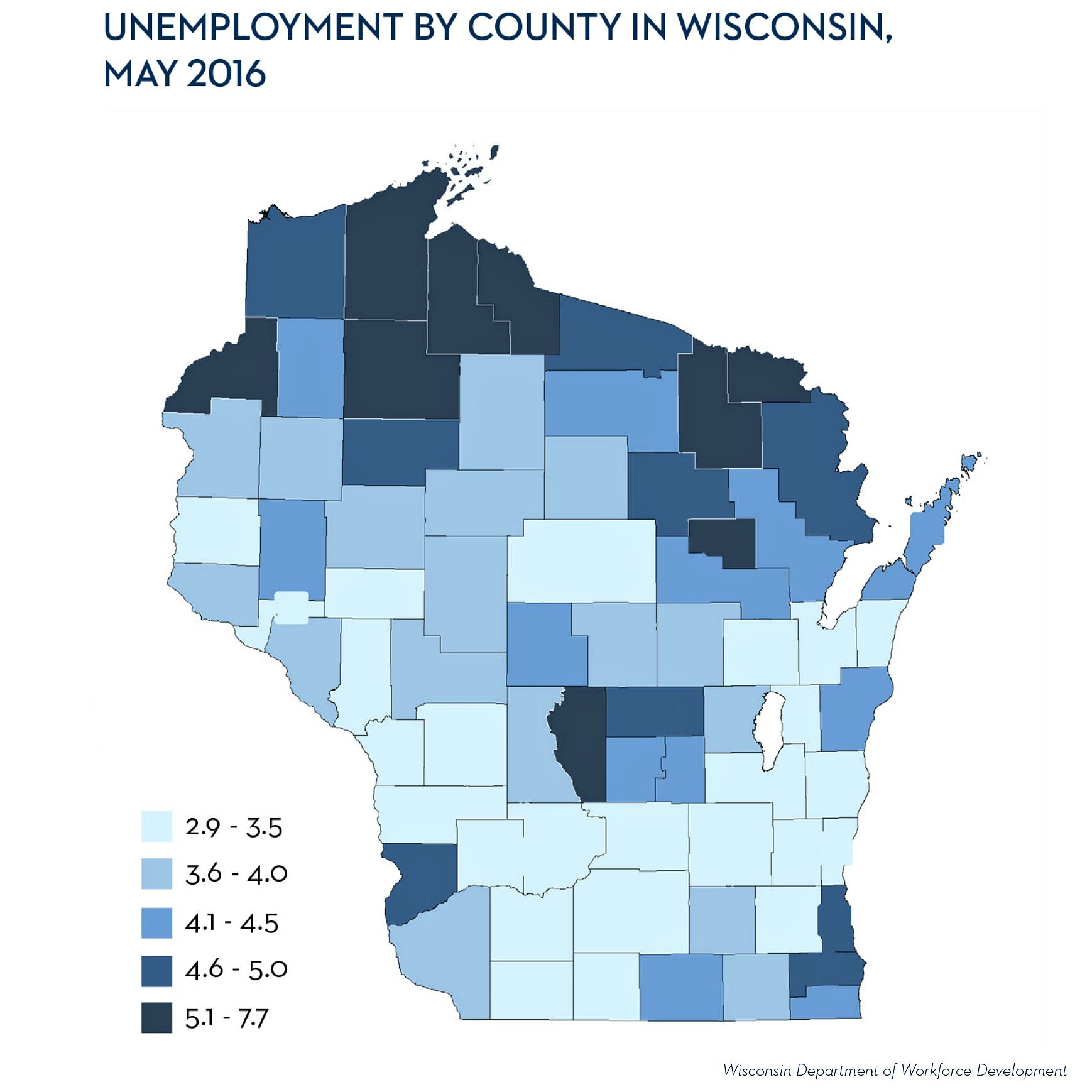

Such is the mixed bag in State of Working Wisconsin 2016, a new report from the Center on Wisconsin Strategy, a progressive policy research institute that is housed at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and describes itself as “nonpartisan but values-based.” Its report notes that unemployment in Wisconsin is down to 4.4 percent — finally dropping below what it was in December 2007 as the Great Recession emerged.

“To be sure, recovery here is incomplete and comparatively unimpressive,” report authors Laura Dresser, Joel Rogers and Javier Rodru00edguez S. wrote, while still acknowledging economic progress made in Wisconsin over the last decade.

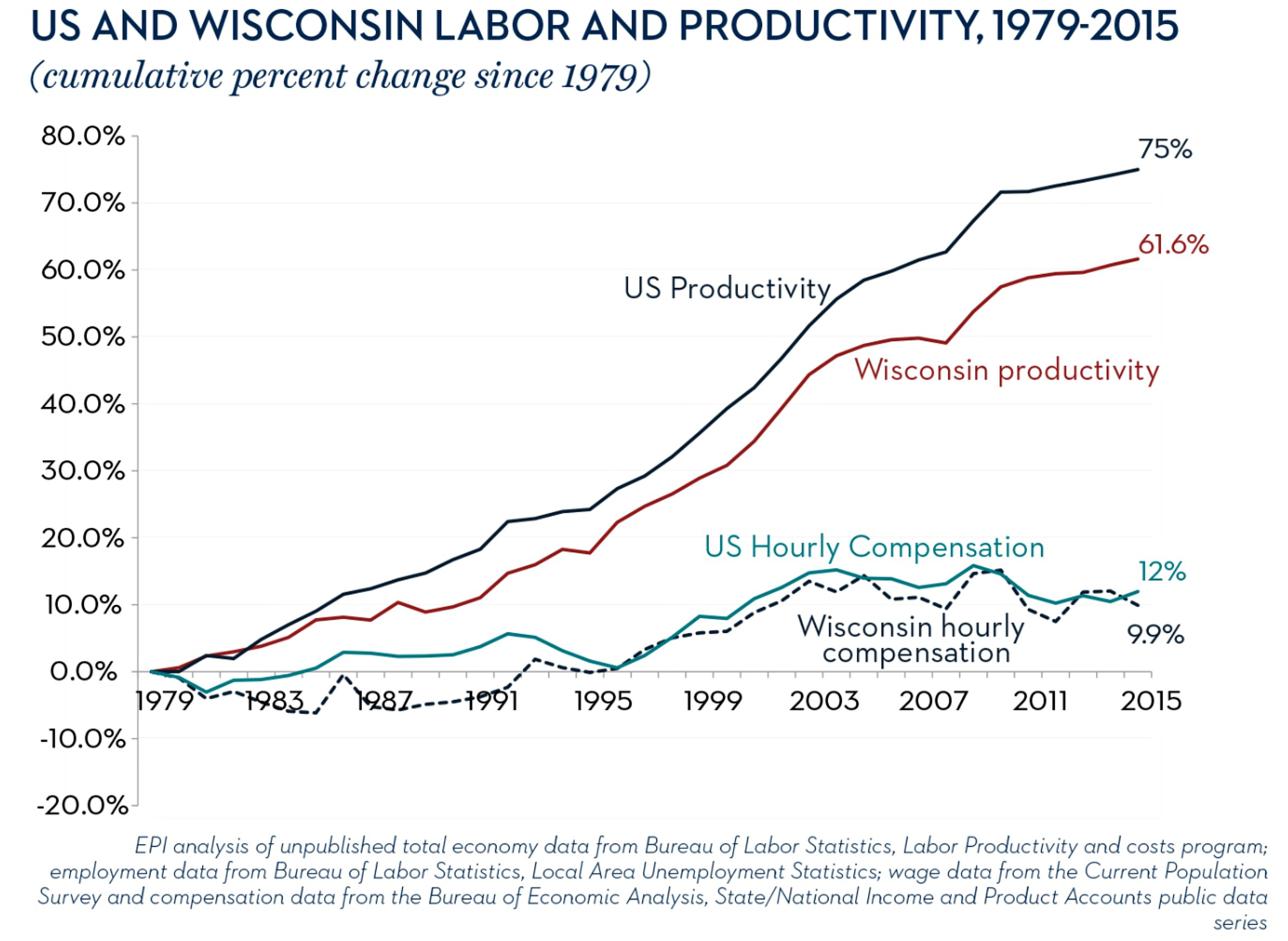

But that job growth hasn’t reversed other economic maladies associated with the recession. Wages have continued to stagnate while productivity climbed, in keeping with the national trend. In 2015, more than one-fourth of the state’s workforce earned poverty wages, which COWS defines as below $11.56 an hour. And fewer workers are getting health insurance from their employers.

Overall, COWS says the job growth is good news, but not what it could be: Wisconsin would have 87,319 more jobs than it has now had its job growth kept pace with that of the U.S. as a whole. Similarly, the state would have added 75,625 more jobs than it has now had job growth kept pace with Wisconsin’s population growth.

In a Sept. 6 interview on Wisconsin Public Radio’s Central Time, report co-author and COWS associate director Laura Dresser said that despite hitting that benchmark of pre-recession unemployment levels, “we’re still in a bit of a hole if you think about where we were in 2007 in terms of total demand.”

The overall picture of Wisconsin’s economy doesn’t reflect the significant disparities that COWS found in its report. The worker who’s barely earning more than she would have 20 years ago, but still has a bit more opportunity than when the recession hit?

“That’s the middle worker,” Dresser said in a Sept. 9 interview on Wisconsin Public Television’s Here And Now. “In 1979, that worker had less education and much less productive technology than today.”

That “middle worker” is still ahead of a lot of other Wisconsinites, though. The report details multiple dimensions of that hole Dresser mentioned.

Geographically, the recovery has been slowest in northern Wisconsin, which has nine of the 10 counties with the highest unemployment rates in the state. Menominee County, located in northeastern Wisconsin and overlapping with the Menominee Indian Reservation, had the highest unemployment rate of all in 2015 at 7.7 percent.

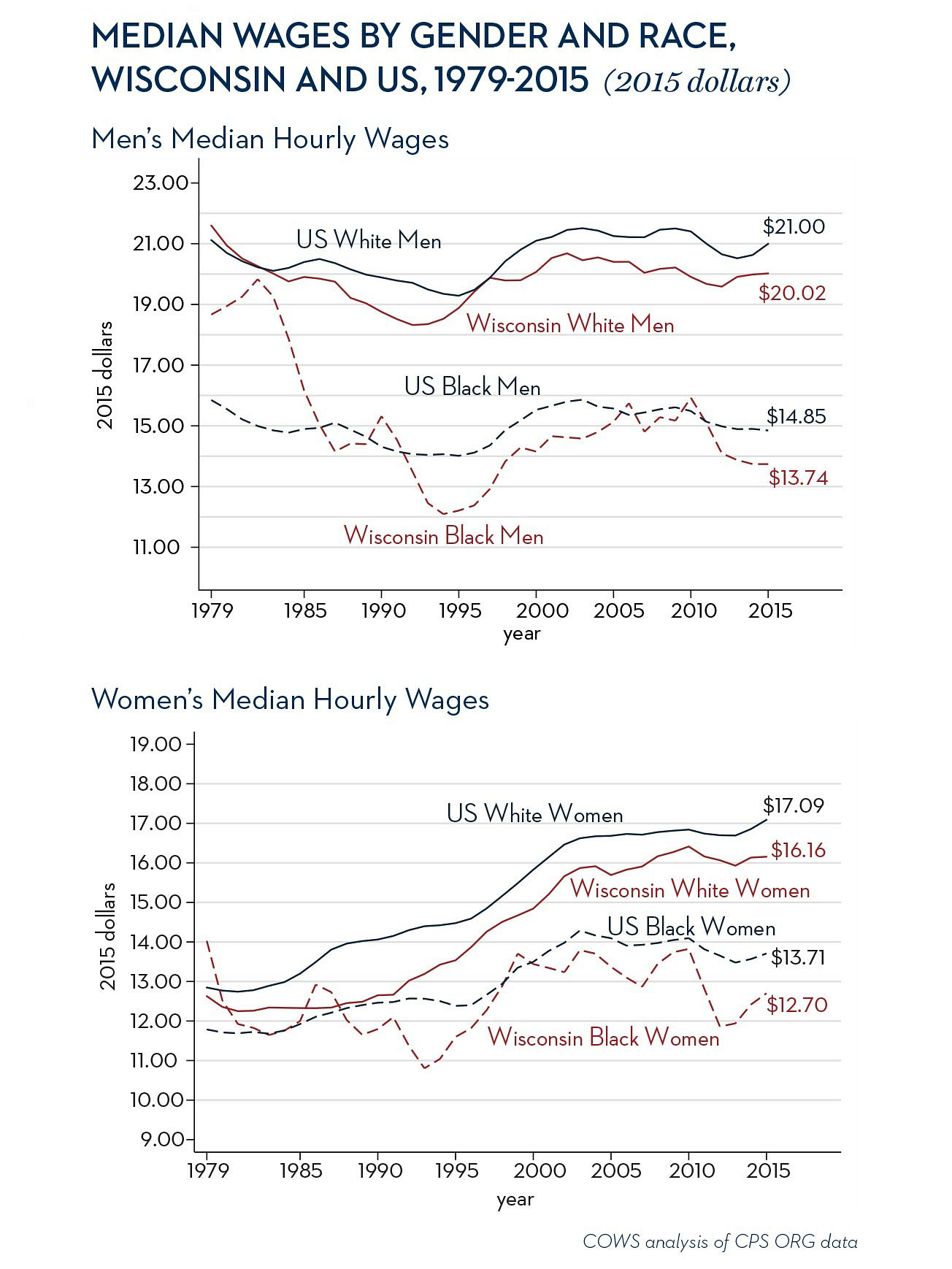

In 2015, African-Americans in Wisconsin had an unemployment rate of 11.6 percent, about three times that of whites. Women had the same unemployment rates as men, but on average earned about 81 cents for every dollar that men earned. Women also tended to be concentrated in sectors where job growth lagged behind the national economy and behind population growth — including education, healthcare, and the financial services industry. The state showed the most job growth in manufacturing, a sector dominated by male employees.

Wages were stagnant for Wisconsin’s workforce as a whole, going up only 1.7 percent between 2000 and 2015. But during that time, the median hourly wage for African-Americans went down by 7.4 percent. The decline was hardest on black women, who saw their median hourly wage decrease by 8.5 percent, while black men’s went down by 4 percent. That pattern is especially striking because women workers overall made wage gains over that same period, as did Hispanic workers, though both continue to earn lower wages than white men.

COWS found that 40 percent of all African-American employees in Wisconsin are working poverty-wage jobs.

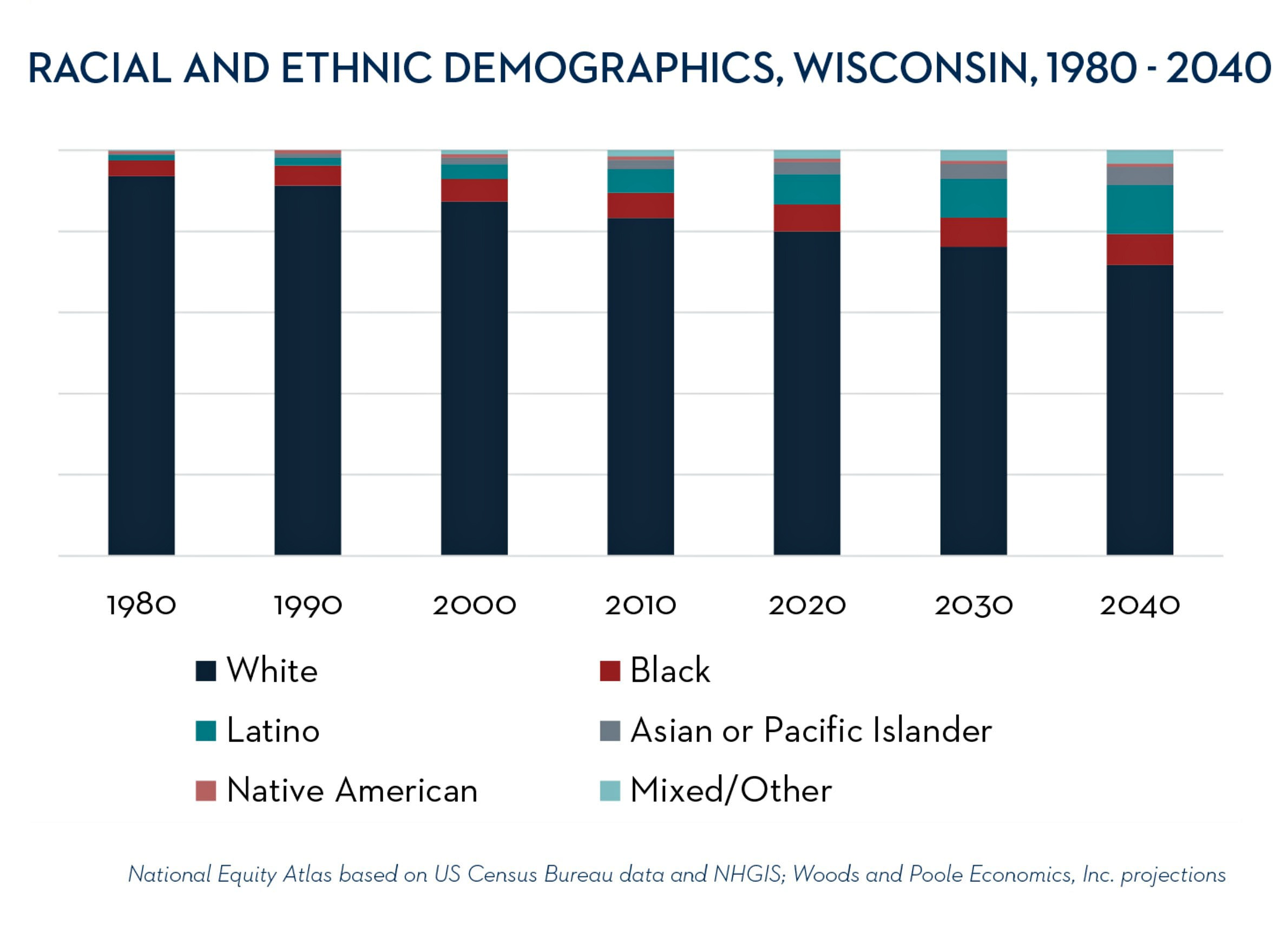

Racial disparities in pay contribute to uncertainty for Wisconsin’s workforce as a whole. “The growing population of people of color further underscores the state’s urgent need to close wage and labor force participation gaps along racial lines,” asserts the report. The state is still projected to be more than two-thirds white in 2040, but people of color will increasingly become a greater percentage of Wisconsin’s population. If these cohorts continue to have less access to opportunity than the white population, the repercussions of that disparity could continue to grow.

COWS offered another note of caution for the future: the state’s population is aging. “By 2020, Wisconsin is projected to lose three percent of the share of prime working-age people (25-54 years old) in the population, dropping to 38 percent. Nationally, this will be a smaller drop, to 39 percent of the population. By 2040, 16 percent of the population will be over 70, compared to just 13 percent of the national population.”

Overall, manufacturing was the most productive part of Wisconsin economy as measured by gross state product, which COWS defines as the value of all goods and services produced in the state. That said, manufacturing is still nothing like what it was at the turn of the century. In May 2000, about 600,000 Wisconsinites worked in manufacturing. In February 2016, though, that number was about 474,000, and that’s after the job recovery detailed in the COWS report.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us