Wisconsin Native languages shift from silence to celebration

A movement to revitalize Indigenous languages is taking root across Wisconsin, as Native speakers teach new generations to speak and celebrate their culture in the wake of decades of forced silence.

By Erica Ayisi | Here & Now, ICT News

June 6, 2025

A movement to revitalize Indigenous languages is taking root across Wisconsin, as Native speakers teach new generations to speak and celebrate their culture in the wake of decades of forced silence.

This report is in collaboration with our partners at ICT, formerly Indian Country Today.

Trinaty Caldwell is learning how to speak Menominee — an indigenous Native American language.

“The ability to talk in the language freely, to be able to do it now today is a blessing because our elders weren’t allowed that freedom,” she said.

Caldwell’s Native ancestors spoke languages that are now nearly extinct. Adult language learners at the Menomini yoU language campus are on a mission to revitalize their Indigenous language from a past of systematic erasure.

“Like even just saying “Posoh” wasn’t always the most comfortable thing right away,” Caldwell said. “Yeah, it’s just, it wasn’t ubiquitous. I didn’t really hear it a lot.”

Ron Corn Jr., the director of revitalization for Menomini yoU, said their doors opened in 2024 after creating a community of Native language learners online.

“There was no meaningful social or community access to the language,” he said. “That means if you’re not looking to be a teacher or be a student, there was no place for you in revitalization.”

The adult learners earn a stipend to normalize speaking Menominee on the reservation.

“When we go and patronize any of the places here on the reservation or do our business — be it at tribal offices and or anywhere else that we might see people who have taken their opportunity to join this revitalization and do that same business in the language,” Corn Jr. explained.

Alexander Medina said he’s now exposed to more conversational Menominee vocabulary that his non-Native stepfather dissuaded him from learning as a child.

“Sometimes it was kind of heavy-handed and kind of bad how much he didn’t want us to basically just be Menominee, like use res slang — we’d get in trouble,” he said.

But now as Medina learns the language, does it have an impact on his self-esteem and identity?

“Absolutely,” he said. “It kind of clicked to me that it’s not illegal. It’s not banned anymore. So we should do what we can to salvage the culture we have left.”

Language revitalization efforts stem from a troubling past.

“The boarding school experience was very effective in what it set out to do, which was to ‘Kill the Indian, save the man’ — and every man, woman and child,” said Corn Jr.. “And our ancestors — three, four generations over — had this horrific life experience.”

For over 60 years, there were at least 11 federal Indian boarding schools across Wisconsin, including two in the Menominee Nation in Keshena. These schools were designed to culturally assimilate Native American children into American culture by forcibly removing them from their families and banning them from speaking their native tongue.

“The most common thread that you see in conversations about language loss really began in the 19th century, particularly in the latter half of the 19th century, and it often revolves around federal Indian boarding schools and Indian schooling in non-Native institutions,” explained Sasha Maria Suarez, a professor of history and American Indian & Indigenous studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She said the federal Indian boarding schools across the state were managed by religious institutions, which colonized Native American children and prohibited their languages.

What was it to be replaced with?

‘English,” said Suarez. “Even if they went into federal and junior boarding schools with no grasp of the English language, that was really the only language they were permitted to speak.”

Severed ties to Indigenous languages have been a generational issue for all tribal communities.

“For over a century, these kinds of policies have tried to diminish and disrupt Indigenous language use,” Suarez said.

“My great-grandma, she spoke Menominee,” said Caldwell. “There were some things that were passed down and some things weren’t, and the language just was not one of them.”

Menominee, Ho-Chunk, Oneida, Ojibwe, Stockbridge-Munsee and Potawatomi are among Wisconsin’s Indigenous Languages.Suarez said these languages did not completely lose their voices.

“Those elders who had been to schools, who maintained an awareness of their Indigenous languages, started using education specifically to teach their languages to the next generations,” said Suarez.

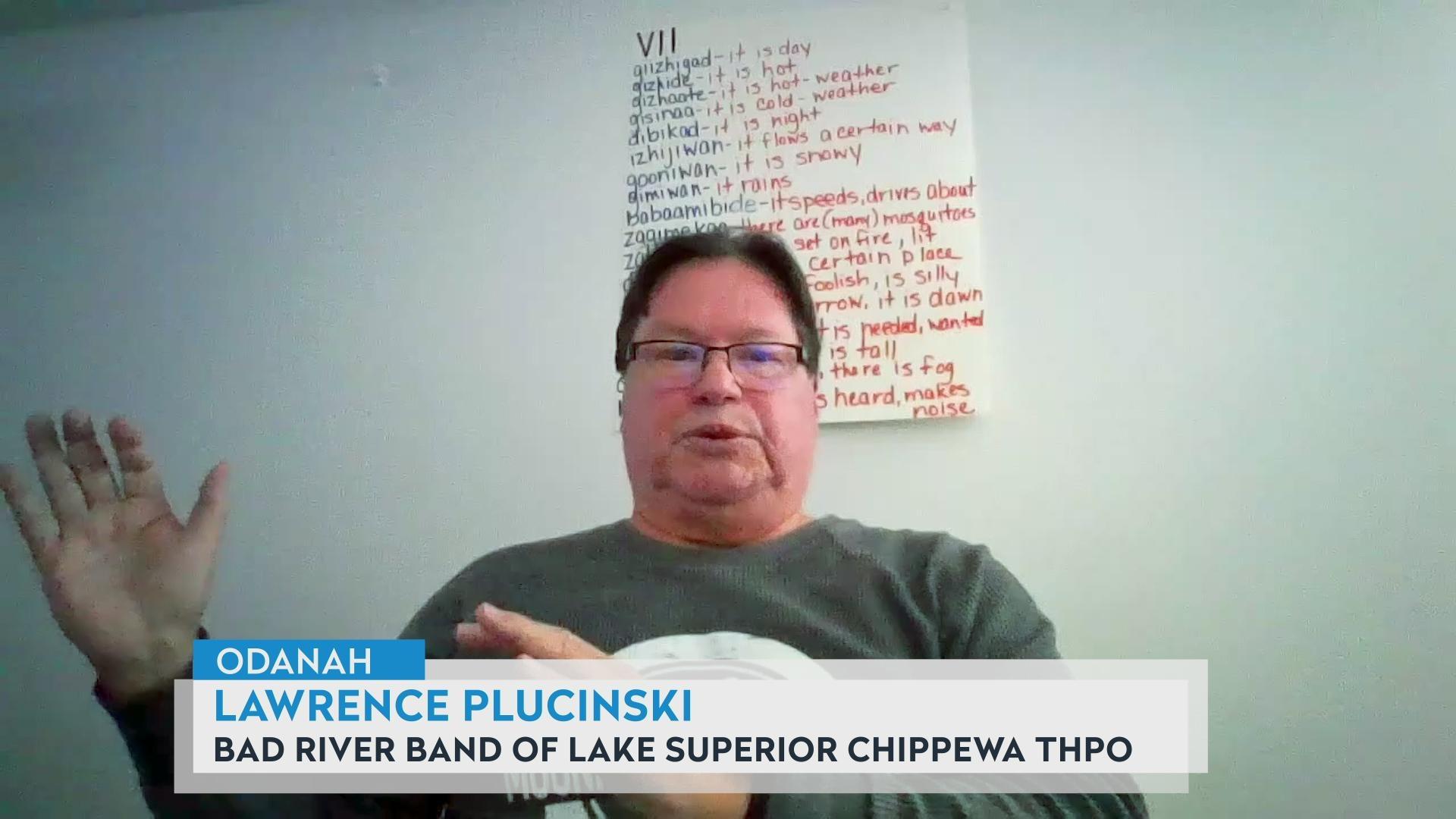

In Bad River, for a new generation of language speakers and singers, Dylan Jennings of the band Bizhiki wants Ojibwe traditional sounds to be a part of the modern music scene.

“We’re expressing ourselves and making things that we like,” he said. “But another part of that too was using our platform to normalize our sounds — our style of singing and our language.”

Their song “Unbound” is about preserving Bad River waters.

“We’re taught that in our cultural and ceremonial circles that we have everything that we need to succeed,” said Jennings. “We just have to remember to utilize our language and all those tools that we’d been given.”

Today, all federally recognized Native tribes in Wisconsin offer Indigenous language learning opportunities.

“The founding of revitalization efforts in those decades following World War II demonstrates really clearly how boarding schools failed in terms of trying to and disrupt Indigenous languages,” Suarez said.

In 2021, Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers issued an executive order formally apologizing for Wisconsin’s role in the Indian boarding schools era.

Four years later at the Wisconsin State Capitol, budget writers are at work fashioning the 2025-27 spending plan, with Republican leaders declaring an impasse in negotiations with Evers. One of the items in the governor’s proposed budget would allocate $11 million in tribal gaming revenue for Native American language revitalization.

Through state and private funding, language revitalization efforts at Menomini yoU plan to continue.

“I don’t have an education beyond high school, but I have a resilient spirit that’s willing to give all that it can to see through the revitalization of the language,” said Corn Jr.

This report is in collaboration with our partners at ICT.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us