Why Volunteers Are Central To Search And Rescue Efforts In Wisconsin

When a hiker goes missing in a forest or a senior with dementia wanders away from a nursing home, who searches for them and under what authority? Or when authorities suspect that a person may have drowned in a lake, how do they go about recovering any remains?

By Will Cushman

January 23, 2020

Sawyer County Search And Rescue team launching boat on lake in Ashland County

When a hiker goes missing in a forest or a senior with dementia wanders away from a nursing home, who searches for them and under what authority? Or when authorities suspect that a person may have drowned in a lake, how do they go about recovering any remains?

In the United States, there is no single answer to these questions. Search and rescue operations and the rules and laws that govern them are as varied as the states and local jurisdictions where they are conducted.

One aspect that’s nearly universal, however, is a heavy reliance on volunteers. With rare exceptions, such as in some large National Parks or maritime settings, volunteers are the backbone of state and local search and rescue apparatuses. This reliance holds true even in places with robust public systems to support search and rescue operations. But how volunteers are trained, deployed and legally protected can differ significantly.

The national search and rescue landscape

There are two broad approaches to search and rescue in the U.S. With some significant exceptions, these sets of policies differ between the western and eastern halves of the nation.

Generally, the more mountainous western states — with their vast unpopulated expanses and challenging terrain — have more developed and systematized approaches to search and rescue.

In California, for instance, a bevy of regulations dictate everything from how local authorities activate a search, to whether and how law enforcement agencies can be reimbursed for their expenses, to what training and protections are required for volunteers.

“Each sheriff in California has a uniformed volunteer organization that is trained to state guidelines for the types of searches that are required,” said Chris Boyer, executive director of the National Association for Search and Rescue, a national nonprofit that provides training for search and rescue volunteers and advocates for laws that offer financial protection to volunteers and their families.

At the other end of the spectrum is Texas. Despite its vast geography posing some similar logistical challenges to those found in California, the Lone Star State lives up to its “Wild West” reputation when it comes to search and rescue practices.

Texas code provides some protections for search and rescue dogs and allows state workers to receive pay for time spent away from their regular duties for training or while volunteering on an active search. However, Texas requires no specific training or certification for volunteers, and no state or local agencies are given sole authority to call or organize a search.

“None of the sheriffs have any responsibility for it,” said Boyer, who lives in Texas. “What’s happened in Texas is a huge number of advocate groups have sprung up.”

There are hundreds of these groups in the state, Boyer explained — their territories overlap, they train differently, they compete and their volunteers have no legal protections. These groups often work directly on behalf of families, rather than at the direction or in concert with local law enforcement. While many of these organizations are altruistic and require rigorous training, some demand payment for their services or are comprised of volunteers with little or no training.

Boyer cited California and Texas as extreme examples of the national search and rescue landscape.

“Every place else in the U.S. falls in the middle somewhere,” he said.

How search and rescue works in Wisconsin

Wisconsin’s approach to search and rescue reflects elements of both California’s highly-regimented system and Texas’s hands-off approach.

State law offers few rules and regulations pertaining to how search and rescue operations should unfold, and it doesn’t set training requirements or protections for volunteers, who are often among the first responders on a scene of a search or rescue. However, Wisconsin code does stipulate that county sheriffs are the designated authorities to “conduct operations … for the rescue of human beings and for the recovery of human bodies.”

Because search and rescue operations in the state fall under the purview of sheriffs, Wisconsin does not deal with a confusing proliferation of competing, and potentially questionable, volunteer search and rescue organizations, as is the case in Texas.

At the same time, sheriffs are not responsible for maintaining rosters of trained local volunteers, and there is no state-mandated training for search and rescue volunteers.

In practice, this system means that when a sheriff activates a search or rescue, the speed and quality of the response can be dictated by the local presence of qualified volunteers — which in many communities is minimal. Additionally, law enforcement may not always be assured that the volunteers who do arrive are properly trained for the tasks at hand, which could include grueling and technical backwoods searches and water rescues, or possibly the use of cadaver dogs. These issues were explored in a Jan. 3, 2020 story on PBS Wisconsin’s Here & Now.

A few local law enforcement agencies in the state do employ staff with specialized search and rescue capabilities, though they are few and far between and are mostly clustered around urban areas. Meanwhile, remote areas in Wisconsin’s Northwoods and the many lakes and rivers statewide provide ample opportunity for tourists and locals alike to get lost,requiring subsequent rescue or recovery services.

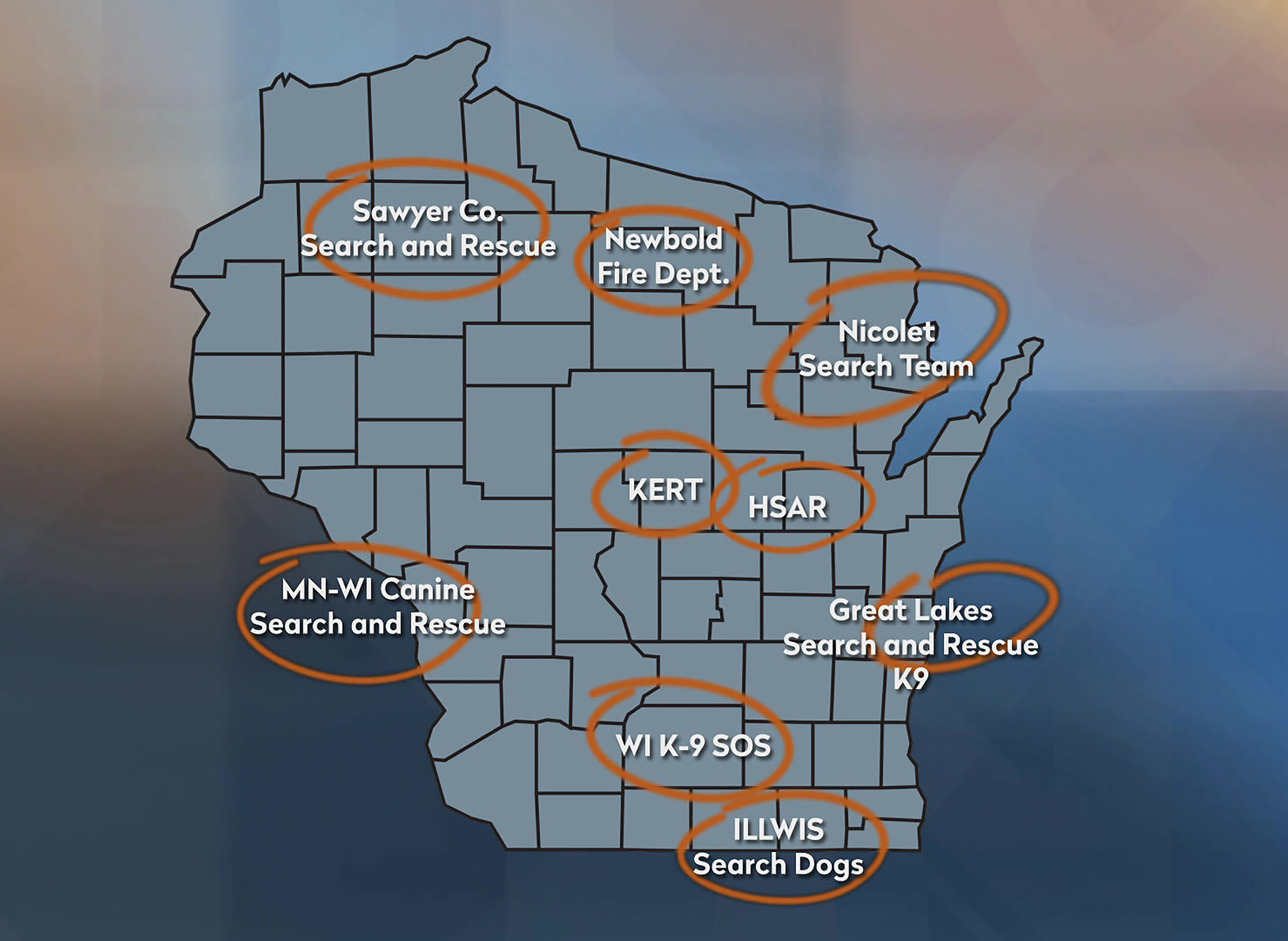

The relative vacuum in qualified volunteers has risen the profile of the active volunteer organizations within the state, which number fewer than a dozen. These include at least four groups with specialties in K-9 search and rescues. Some groups, including one in Sawyer County, have developed such good reputations that sheriffs from surrounding counties and beyond will request their services under Wisconsin’s mutual aid rules.

Meanwhile, the state also provides support upon request, though this usually occurs when the scope of a search or rescue is beyond the means of local law enforcement and the volunteers they’re able to muster.

“The state only comes in if we have an asset that could help,” said Andrew Beckett, a public information officer for the Wisconsin Department of Military Affairs. The agency is responsible for the state’s emergency response apparatus, called Wisconsin Emergency Management.

State assistance usually comes in the form of aerial support, Beckett said. Wisconsin Emergency Management has organized the Wisconsin Air Coordination Group in cooperation with the State Patrol, Department of Natural Resources, Capitol Police, county sheriff’s departments and the Wisconsin Drone Network. The latter group was established as a growing number of law enforcement agencies in the state use drones for various purposes.

“That’s a resource that’s really been built up over the last few years to capitalize on drone technology,” Beckett explained, adding that Wisconsin Emergency Management receives about 30-40 requests a year for aerial support, though not all of those requests are for search and rescue operations.

“Search and rescue really starts and occurs at the local level,” he said.

One search and rescue arena that works quite differently and receives national support is urban search and rescue. In Wisconsin, a task force made up of fire departments from a dozen cities brings expertise in responding to natural disasters, large-scale accidents and terrorist attacks.

Chris Boyer, the national search and rescue association director, said most urban search and rescue infrastructure in the nation is funded through the federal government, which began in response to the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake in California. Boyer said that funding and support for urban search and rescue has been a governmental priority as opposed to other types of search and rescue, such as when people get lost in wilderness environments. He explained that the situations are quite different, and firefighters and emergency professionals are already so heavily involved in disaster response.

“It’s very much a fire department issue,” Boyer said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us