What the 2022 bird flu outbreak means for Wisconsin poultry

Poultry producers and government regulators in Wisconsin are closely monitoring the spread of the H5N1 avian influenza virus among chickens, turkeys and wild birds around the state, putting biosecurity measures in place and depopulating infected flocks.

By Will Cushman

April 14, 2022

(Credit: U.S. Department of Agriculture)

A flu virus that’s deadly to birds and easily spreads among them has poultry producers in Wisconsin on high alert. An outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza in spring 2022 is the most serious in North America in seven years.

While it poses a minimal threat to human health, the virus can wipe out backyard chicken flocks and massive poultry operations alike. Moreover, with food prices already climbing due to higher energy prices and pandemic-related supply chain difficulties, this bird flu outbreak carries the potential to raise the prices of poultry and eggs even further.

Here’s what to know about the outbreak and its impact on Wisconsin.

What is the strain behind the outbreak?

There are a number of influenza viruses that can infect and sicken various species of animals, including birds, pigs and humans. The virus spreading among wild birds and poultry farms around North America in spring 2022 is a Type A avian influenza labeled H5N1.

The H5N1 subtype primarily infects and sickens birds. It differs from another common avian flu subtype in its ability to severely sicken and kill large numbers of birds. As such, the highly pathogenic subtype poses a major risk for poultry and egg producers.

Where did the outbreak originate?

The H5N1 virus currently spreading in North America previously spread globally among wild birds, causing occasional outbreaks in poultry operations around the world.

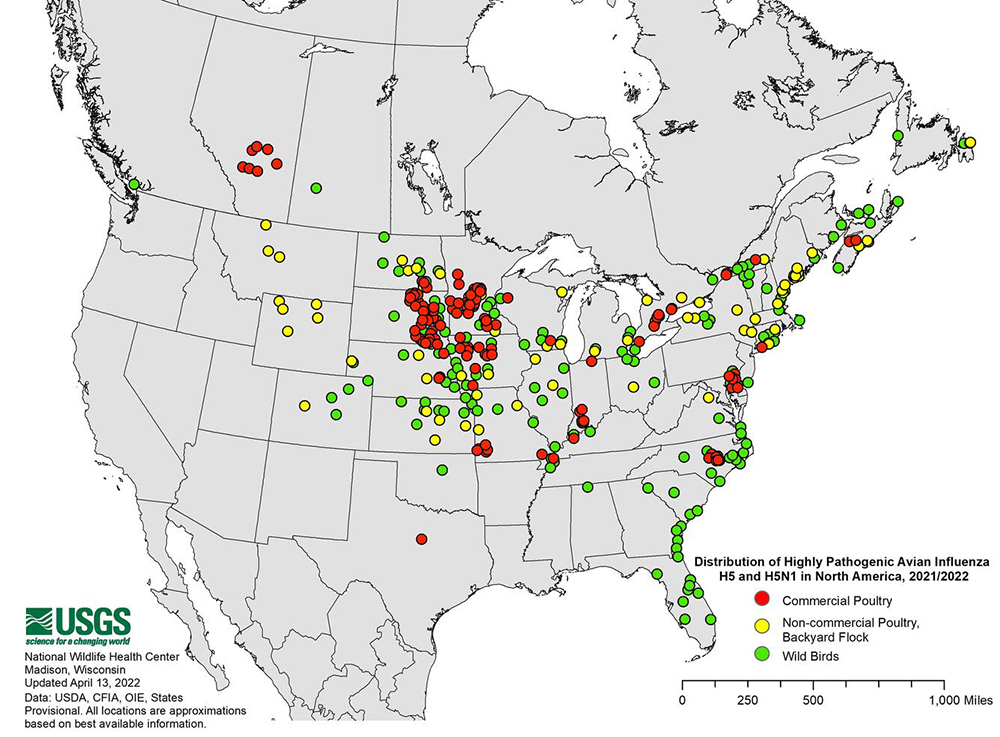

The virus has quickly spread among birds across North America since its first detection on the continent in December 2021. As of April 13, the virus had been identified among wild birds, backyard poultry flocks or commercial operations in nine Canadian provinces and 35 states, including Wisconsin, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The virus’s spread has accelerated northward with the spring migration of many North American bird species, explained Ron Kean, a poultry specialist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison Extension.

Where has the virus been found in Wisconsin?

The H5N1 bird flu has been found among wild birds, in backyard chicken flocks and at multiple poultry operations across Wisconsin in spring 2022.

The virus was first confirmed in the state on March 14 in an enormous egg farm in Jefferson County that housed more than 2.7 million laying hens. In its announcement of the virus’s confirmation, the Wisconsin Department of Trade, Agriculture and Consumer Protection noted it was the first detection of H5N1 in Wisconsin since the massive North American bird flu outbreak in 2015.

(Credit: National Wildlife Health Center / U.S. Geological Survey)

At the end of March, the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources announced the virus had been identified in wild birds of various species around the state, including in Columbia, Dane, Grant, Milwaukee and Polk counties.

Over the first half of April, the virus has been confirmed in two backyard flocks — in Racine and Rock counties — as well as at a large commercial operation in Barron County housing around 50,000 turkeys. The operation is owned by the massive turkey supplier Jennie-O, which has a large presence in western Wisconsin and Minnesota. The Barron County operation joins “a significant number of farms in [Jennie-O’s] supply chain in Minnesota” impacted by the bird flu outbreak, according to an April 9 update from the company.

How are regulators and producers responding?

The H5N1 outbreak has poultry farms and agricultural regulators in Wisconsin keeping close tabs on the situation. The state agricultural agency recommends farmers move their flocks indoors if possible to reduce the risk of transmission from wild birds.

Commercial and non-commercial flocks can also be protected by strict adherence to biosecurity protocols that include proper disinfection of equipment, limiting visitors, wearing clean clothing and footwear and limiting traffic between farms.

The undercarriage of truck is washed before departure as a container leaves a premises with organic materials from a depopulated flock in northwest Iowa during the 2015 H5N1 avian influenza outbreak. (Credit: Mike Milleson / U.S. Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service / Flickr at https://www.flickr.com/photos/usdagov/17840535114/ / CC BY 2.0 / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

Farmers who suspect disease within their flocks should contact DATCP’s Division of Animal Health, which coordinates testing for the virus and other diseases. Common symptoms of infection in poultry include sudden death, lack of energy or appetite, decrease in egg production, purple discoloration of parts of the body lacking feathers, difficulty breathing and other respiratory symptoms, stumbling, diarrhea.

If the virus is confirmed within a flock, regulators from the United States Department of Agriculture and DATCP will coordinate the “depopulation” of the flock.

“It’s more humane to euthanize than to let them die from the disease,” said Kean, the Extension specialist. Additionally, he said swift killing of the flock helps reduce the risk of the virus spreading elsewhere. The USDA details two primary depopulation methods: water-based foams or carbon dioxide gas, both of which suffocate the birds.

Depopulated flocks are usually composted, ideally on-site and indoors, according to Kean, before a farm can repopulate its flock.

Does this bird flu pose a threat to humans?

While the H5N1 bird flu can infect non-avian species, transmission to humans is rare and usually limited to those who are in close contact with infected birds, such as workers on poultry farms, according to the CDC. The agency has also indicated that the 2022 outbreak “poses low risk to the public.”

Since its emergence in the 1990s, highly pathogenic bird flu has been confirmed to have infected fewer than 1,000 people worldwide. While the virus has killed more than half of the people it has infected, human-to-human transmission has been extremely rare and limited. Signs of bird flu infection in humans range from no symptoms, to mild flu-like symptoms to severe pneumonia, accompanied by a high fever, body aches, fatigue and other respiratory symptoms.

Noting the evidence that bird flu rarely spreads among humans, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services indicated there was “no imminent threat to Wisconsin” following the virus’s confirmation in the state.

Additionally, bird flu does not make poultry or eggs unsafe to eat, according to the USDA.

“It shouldn’t be a food safety concern,” said Kean.

On the other hand, the loss of a large number of birds would likely continue to elevate the prices of poultry and eggs, at least temporarily, Kean added.

How long will the outbreak continue?

Kean said it is difficult to predict how long the current bird flu outbreak might pose a threat to poultry operations in Wisconsin. He noted the risk of infections from wild birds should decrease as the spring migration winds down, though some researchers have expressed surprise at how well this iteration of H5N1 has been able to persist among wild birds globally. On top of that, the risk of transmission between commercial flocks could remain as long as the virus remains in circulation. He said that strict adherence to biosecurity protocols should minimize that risk.

Additionally, Kean said the risk of spread would likely remain heightened if Wisconsin continues to experience springtime temperatures on the colder side, noting that the virus survives better in cooler temperatures.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us