What A Simple Test Can Say About Lifelong Traumas, Individually And Across Wisconsin

Children who suffer abuse or neglect or who live in dysfunctional homes often carry the burdens of these experiences into adulthood. Behavioral health professionals call these ordeals "adverse childhood experiences," or ACEs.

By Will Cushman

May 14, 2019

Not Enough Apologies ACEs categories screenshot

Children who suffer abuse or neglect or who live in dysfunctional homes often carry the emotional, mental and physical burdens of these experiences into adulthood.

Behavioral health professionals call these ordeals “adverse childhood experiences,” or ACEs. The term originates in a 1990s study that linked childhood abuse and household dysfunction to risk factors for several of the leading causes of death in adults, including heart disease and cancer.

In a questionnaire, researchers asked more than 17,000 people whether they had experienced 10 specific ACEs — from neglect to sexual abuse to persistent hunger — during their childhood. Each “yes” added one point to a participant’s ACE score. A final score of zero indicated a childhood free from the 10 adverse experiences asked about in the questionnaire. Meanwhile, higher scores indicated a childhood with more adversity.

Researchers also probed participants’ health behaviors and current health status. They found the groups of people who had experienced more ACEs were also more likely to have health problems or were at risk of developing health problems as a result of their behaviors.

The ACE test has become a popular public health awareness tool, and countless people have taken it to better understand the potential effects of adversity within the context of their own lives.

The original ACE study has since influenced the understanding of lived experience as it relates to behavioral health. The basic idea is that adverse childhood experiences can have a lasting impact on public health and quality of life by possibly affecting future behavior and decisions. Its broader findings are still used for understanding population health risks.

What survey results say about ACEs in Wisconsin

Data from a multi-year survey in Wisconsin show just how prevalent ACEs are in the state.

In 2010, the state Department of Health Services began including an ACEs questionnaire that closely resembled the original study as part of the its Behavioral Risk Factor Survey. The survey is conducted annually in coordination with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 25,000 Wisconsinites were surveyed over a 5-year period through 2015.

The survey’s findings were summarized in several reports, culminating in a May 2018 publication released by the state’s Child Abuse & Neglect Prevention Board. The surveys showed that more than half of adults in Wisconsin have an ACE score of at least 1, while 14% have an ACE score of 4 or higher.

The Wisconsin-specific ACEs surveys found a link between ACEs and adult income, along with racial disparities in experiences of childhood adversity. Similar to the original ACE study, the Wisconsin surveys also showed that a higher number of ACEs were linked to higher rates of depression, poor health, chronic health conditions and increased health risk behaviors, including risky sex, tobacco use and heavy drinking.

ACEs don’t necessarily lead to trauma, but they often do

The reality for individuals who have experienced traumatic events is usually much more complicated than a simple questionnaire.

That’s because ACEs do not necessarily lead to trauma, and even when they do, trauma can manifest itself in any number of ways, many but not all of which are unhealthy.

“ACEs and trauma are not interchangeable,” said Sara Daniel, vice president of educational services at SaintA, a human services organization headquartered in Milwaukee that serves clients around Wisconsin.

“An ACE is something that happens to you, and trauma is the impact of that experience and your capacity to respond … and ability to adapt or function,” she said.

Understanding the difference between ACEs and trauma is important, Daniel explained, especially with regard to the ACE test specifically, which asks about a limited scope of adverse experiences. She has witnessed firsthand the potential damage of conflating an ACE score with evidence of trauma.

“I’ve seen people say ‘Oh my gosh, I have a high ACE [score]. My life is over,” she said. “That’s a fatalistic response to an oversimplification of traumatic load.”

ACEs and their relationship with childhood trauma were explored in Wisconsin Public Television’s May 2019 documentary Not Enough Apologies, which explores how trauma affects Wisconsinites and the systems that serve them. A segment from the documentary discusses how children respond to traumatic experiences.

Daniel values the ACE test as a public health and educational tool, though she said it should not be used to screen patients or to make diagnoses. That’s because an individual ACE score can only indicate potential for trauma.

“Trauma is held very personally,” she said. “Somebody can have horrible things happen to them — violence, sexual abuse — but if they have resilience or relational buffers, they [can] find a way to cope and overcome. And then you can have somebody who doesn’t have those things and gets into a car accident, and it can change their life.”

Ronnie Pierce and Jameelah Love grew up living in foster care and have since become involved in SaintA’s “Youth Transitioning to Adulthood” program. Pierce and Love described how childhood adversity affected their lives for Not Enough Apologies.

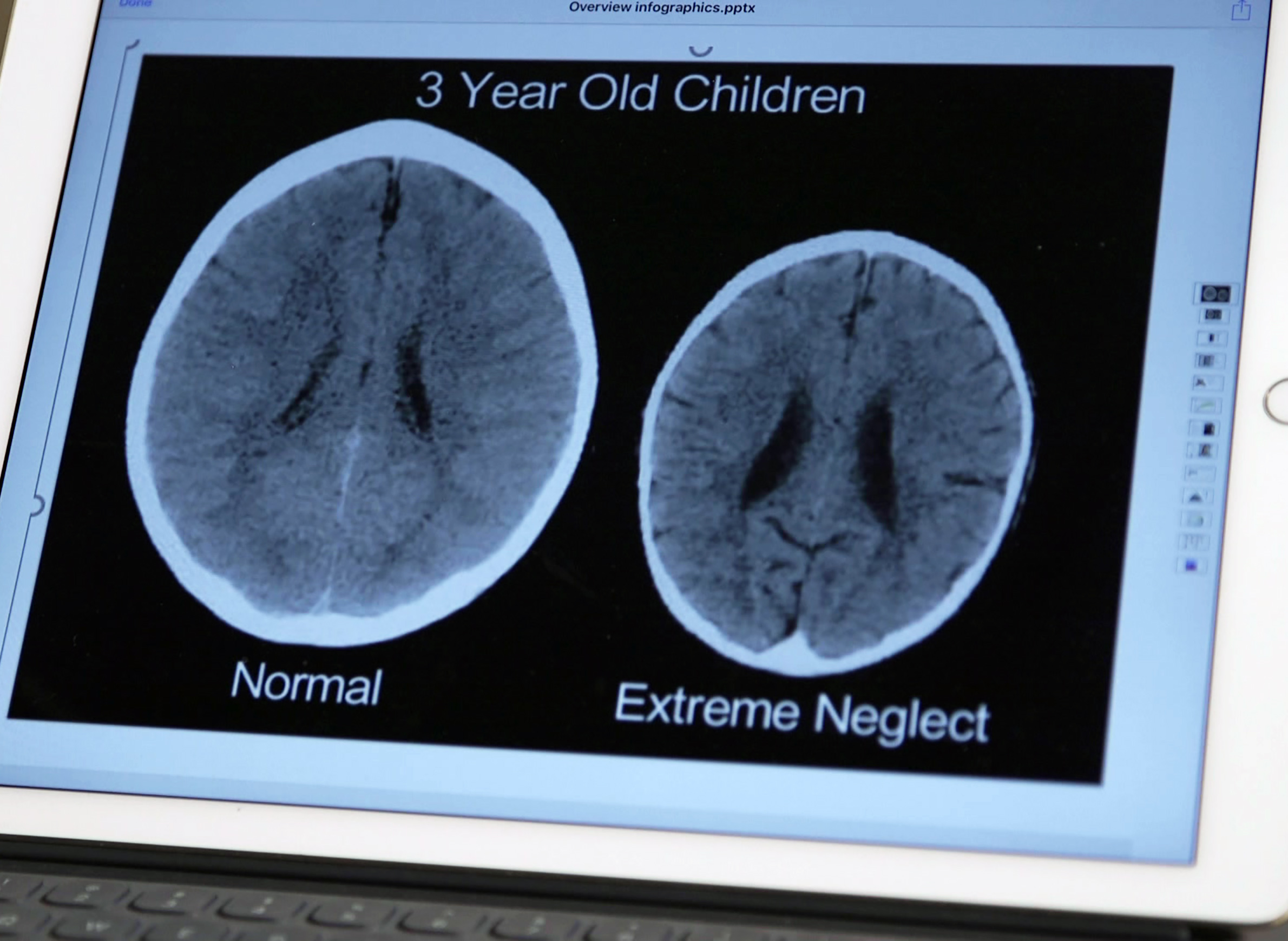

SaintA takes what is called a neurodevelopmental approach with its clients. Grounded in a scientific understanding of brain development, this model of care considers not only the type and degree of adversity a child has faced, but factors like whether the child has had healthy relationships with adults that could help mitigate the adversity’s impact, as well as when the child experienced adversity.

“It’s important what the event is, when it occurred and who was there,” Daniel said. An adverse experience can lead to lasting changes in the structure of the brain, depending on when during brain development it occurred, and whether there were other factors that could have lessened its impact.

All of these variables influence how children, and later adults, adapt to traumatic experiences, Daniel explained. Those adaptations could be unhealthy, such as gravitating toward toxic relationships, self medicating with alcohol or drugs, zoning out by binging on television or video games or participating in risky sexual behavior.

“But there are plenty of people with high ACE scores who adapt through healthier behaviors,” Daniel said. “Manifestations of trauma are not necessarily unhealthy behaviors.” Similarly, she added, not all people who partake in unhealthy behaviors have experienced trauma.

Perhaps the most important conclusion Daniel hopes people make after taking the ACE test is that children of all backgrounds experience adversity.

“The first conclusion of the ACEs study is that ACEs are common,” she said. “ACEs don’t happen to those people over there. It’s not some at-risk community. It’s happening to your friends, your neighbors, your colleagues.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us