Transforming Inmates Through The Drama Of Shakespeare

In an era of mass incarceration, the arts can offer prison inmates an opportunity for personal growth and help them prepare to re-enter society.

October 17, 2017

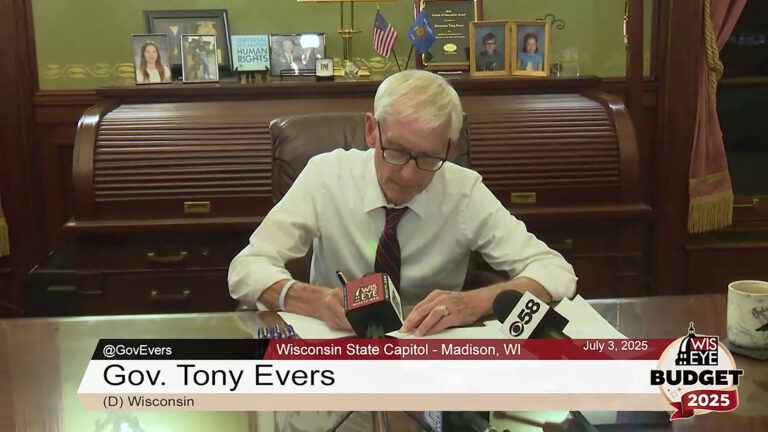

Othello performance in the Shakespeare Prison Project

In an era of mass incarceration, the arts can offer prison inmates an opportunity for personal growth and help them prepare to re-enter society. At least, that’s the hope of educators like University of Wisconsin-Parkside communications professor Jonathan Shailor, who founded the Shakespeare Prison Project. Launched in 2004, the project works with incarcerated men at Racine Correctional Institution in Sturtevant to help them grow on a personal level and turn their lives around.

Throughout each cycle of the project, Shailor has worked with a group of inmates — who serve as actors and production assistants — in a year-long process of studying and eventually performing a full multi-act Shakespeare play. “An environment very unlike the prison yard and many prison classrooms develops where creativity and compassion, self-exploration and experimentation, playfulness and risk-taking can flourish and bear fruit,” he said.

Prisons in other states around the U.S. have Shakespeare-focused theater programs too, including Shakespeare Behind Bars and similar efforts for both women in Michigan and men in New York.

The Bard isn’t the only arts-driven vehicle for helping people caught up in the criminal justice system. Other efforts in Wisconsin and around the nation have tried to harness creativity for this purpose, like a Madison Public Library program for teens and the Oakhill Prison Humanities Project, whose activities included exhibitions called “Artists In Absentia” that presented visual art by prisoners.

Shailor edited the 2010 book Performing New Lives: Prison Theater, a collection of essays from people who are involved with drama-based programs at correctional institutions across the country. He discussed the book and the Shakespeare Prison Project in an Oct. 23, 2016 talk at the Wisconsin Book Festival in Madison. His talk was recorded for Wisconsin Public Television’s University Place.

In his presentation, Shailor described how the project works, including how inmates come to identify with the characters they play through the rehearsal process, and the logistical hurdles of incorporating realistic weaponry and fights into a performance in a prison. He also discussed the intellectual, social, and emotional benefits performing Shakespeare offers to inmates, and how their productions reveals participants’ eagerness to be transformed.

“Prison theater programs can be a crucible for transformation,” he said. “Prison theater programs are places of refuge where the imaginations, hopes, and humanity of the incarcerated can be more fully expressed.”

Key facts

- Wisconsin not only incarcerates African-Americans and Native Americans at disproportionately high rates compared to the state’s population, but also does so by greater margins than any other state in the nation.

- Racine Correctional Institution is over capacity by about 400 inmates.

- About 30 percent of the population at Racine Correctional Institution are sex offenders, and therefore so are a fair number of people in the Shakespeare Prison Project.

- The plays performed by the Shakespeare Prison Project have included King Lear, Othello, The Tempest, Julius Caesar, Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Merchant Of Venice. During the process of studying and rehearsing the plays, inmates also have opportunities to develop their own works, including original poems that are sometimes incorporated into the performances.

- Shailor does not see the Shakespeare Prison Project as a form of therapy, but says it can be therapeutic, and can help participants better understand themselves. The project focuses on helping inmates to draw on emotions from their own life experiences that can be related to those of Shakespeare’s characters. For example, an inmate who had a difficult relationship with his own mother channeled his feelings about that into the role of Cordelia in King Lear. Cordelia is Lear’s favorite daughter, but he ends up disowning her. By challenging inmates to see themselves in new ways and work as a team, prison theater programs intend to help prepare them for eventual re-entry into society.

- Shakespeare’s tragedies involve a fair amount of violence, which creates some logistical challenges when staging them in a prison. The Shakespeare Prison Project had to get approval from prison officials for stage weapons used in plays. Initially, the productions used a martial-arts practice tool called escrima sticks, and Shailor even hired a professional fight director to help the inmates perform convincing fight scenes. Racine Correctional Institution ended up wanting to change its approach, though, so inmates learned to craft their own stage weapons using cardboard.

Key quotes

- On why Shailor and inmates connected so strongly with King Lear and Cordelia’s predicament: “It’s about a child — who is a favored child — who is secure as long as that favored child has the confirmation of an overwhelming, overbearing parent. The universe will hold together as long as that relationship is OK, but that doesn’t leave much room for growth on the part of the child, and also the parent is horribly lost… For me, it was a profound opportunity to reflect on some dynamics in my own family life, and perhaps not surprisingly, it connected in powerful ways with the prisoners that I worked with at Racine Correctional Institution.”

- On how playing Cordelia affected one inmate: “He would reflect on this experience as the purest of emotional therapy. He said, ‘I am Cordelia. I am Cordelia in so many ways, and in being her, I am learning me.'”

- On the social value of prison theater programs: “One of the bitter ironies of the U.S. prison system is that the emotions that cause people to end up in corrections — fear, detachment, hatred, anger — are often further fed by incarceration. Instead of a respite from these destructive feelings, prison tends to create a super collider for them. Prison theater programs create sanctuaries where the distractions and the degradations of the normal prison context are temporarily set aside. A safe container is established where focus and discipline can be exercised in the service of artistic goals. A sense of ensemble or community can develop, offering both challenge and support to each of the participants.”

- On why inmates in the program choose the roles they do: “These are masks that the men can put on and use as a vehicle, a safe medium to explore a wide range of their own emotions,ideas, to kind of stretch and to investigate.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us