The Novel Coronavirus And How Isolation And Quarantine Authority Works In Wisconsin

In the arsenal of weapons available to public health officials for combating outbreaks of infectious disease, quarantines are among their most serious options.

By Will Cushman

February 5, 2020

N-95 respirator mask and apparel for disease outbreak illustration

In the arsenal of weapons available to public health officials for combating outbreaks of infectious disease, quarantines are among their most serious options. As a result, quarantines are usually reserved for the most serious — or potentially serious — public health threats.

As authorities around the world employ quarantines of unprecedented scale in their efforts to halt the spread of a new virus emanating from central China, they are signaling to the public that the threat this illness poses is extraordinary — or at least could be.

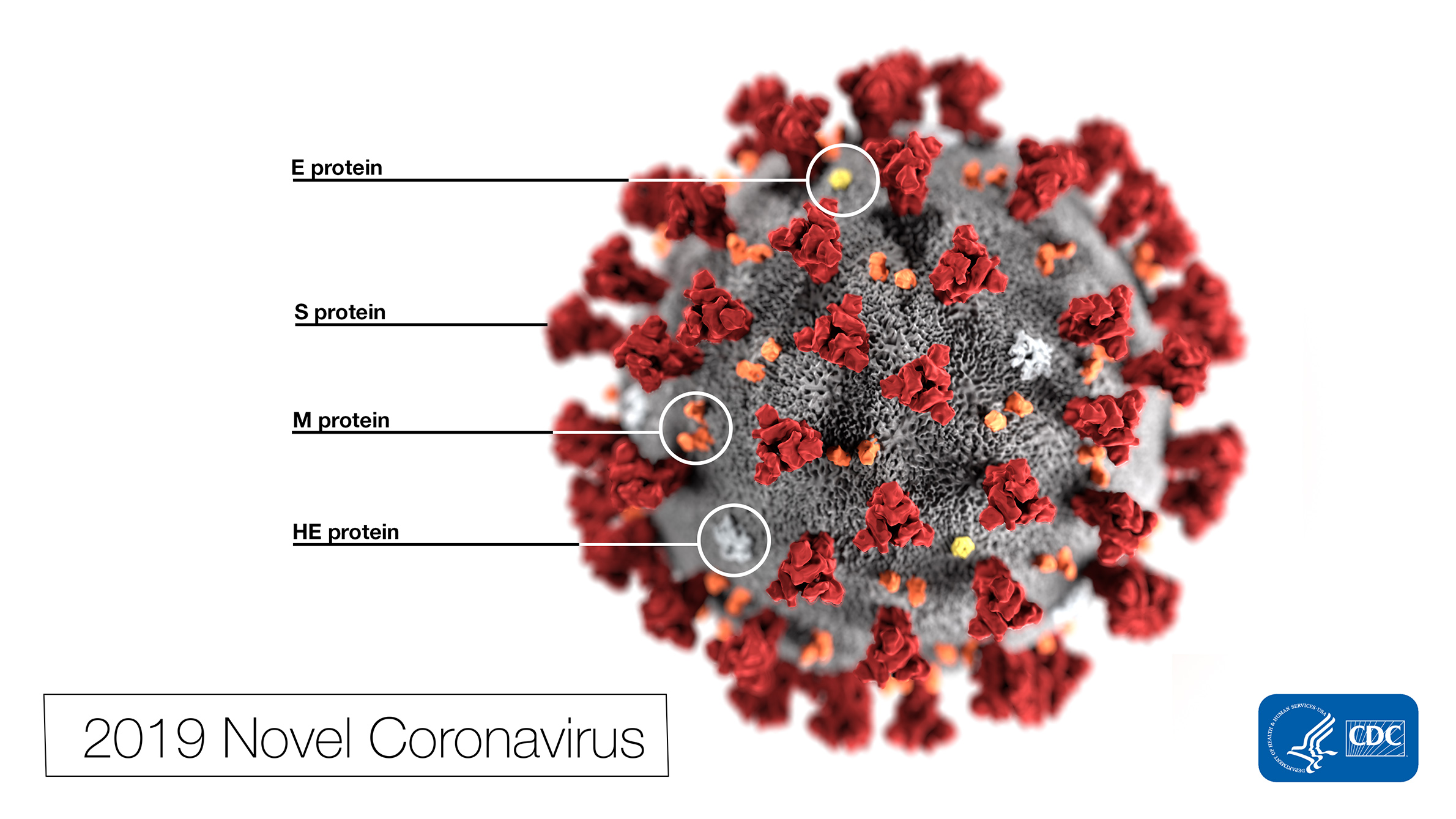

These signals began on Jan. 23, 2020, when the Chinese government abruptly shut down travel links to and from the city of Wuhan, effectively sealing off millions of its residents from the outside world. Wuhan is at the epicenter of a newly identified coronavirus — known in medical settings as 2019-nCoV — which first appeared in December 2019.

The respiratory virus has since been confirmed to have killed hundreds and sickened tens of thousands in Wuhan and the surrounding province of Hubei. But as new cases crop up across China and around the world, much remains unknown about the novel coronavirus, including how easily it spreads and how often it leads to serious illness or fatal complications.

Partly in response to these unknowns, government authorities in multiple nations swiftly expanded the use of quarantines in the days following the confinement of Wuhan.

These actions have been most dramatic in China, where an authoritarian government has wide latitude to implement social controls. The quarantine originally sealing off Wuhan quickly expanded to much of Hubei, encompassing a population of nearly 60 million people. The draconian measures were likely too little too late to halt the virus’s spread, an international group of researchers warned.

Other nations are also imposing quarantines, albeit on more limited terms. The Japanese government quarantined a cruise ship carrying thousands of passengers and crew members after a passenger tested positive for 2019-nCoV. Australian officials controversially quarantined citizens evacuated from Wuhan on a remote island in the Indian Ocean. European governments are also quarantining evacuees from Wuhan and Hubei province.

The United States has imposed mandatory 14-day quarantines for travelers arriving in the nation from Hubei province, marking the first time the federal government has flexed its quarantine powers in 50 years.

Additionally, Americans arriving from anywhere in China are being funneled to international airports that house Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quarantine facilities, where they are being screened for symptoms of 2019-nCoV. Possible signs of infection include fever, cough and shortness of breath. Travelers and some state officials have complained that the federal government’s quarantine and related travel orders have led to some confusion.

At the same time, state and local health officials in the U.S. where patients have tested positive for the novel coronavirus have swiftly isolated those patients and asked close contacts to separate themselves from others as much as possible.

Technically, a quarantine is an intentional separation from the wider population — whether voluntary or forced — of individuals or groups of people who may have been exposed to an infectious disease but who have not shown symptoms or tested positive for the pathogen. Quarantines apply only to individuals who appear healthy; patients who already have an infection and who are separated from the population are considered to be in “isolation.”

Quarantines were established as a public health tool long before the advent of modern medicine. Amid outbreaks of plague in 14th-century Europe, known to history as the Black Death, merchant ships arriving in Venice from infected ports were required to remain anchored offshore for 40 days. Italian for “40 days” is quaranta giorni.

The U.S. government has imposed quarantines to control the spread of infectious diseases like cholera, yellow fever and influenza since the 19th century. Over the decades, the roles of federal and local health agencies have evolved with regard to quarantines and other public health orders. The CDC offers an in-depth history of these shifting responsibilities.

Public health powers in Wisconsin

On Feb. 5, 2020, Wisconsin confirmed its first 2019-nCoV infection. Over the previous week, a smattering of potential cases under investigation had state and local officials ramping up to respond. (Meanwhile, these preparations are occurring while public health officials remain focused on influenza, which is circulating widely in Wisconsin.)

Any novel coronavirus responses would undoubtedly include weighing whether to impose and enforce isolation and/or quarantines on Wisconsin residents and visitors, as well as deciding how widely to impose the latter.

“It’s really up to public health authorities to figure out how broadly [a] quarantine order needs to be implemented,” said Patrick Remington, an emeritus professor in the Department of Population Health Sciences at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

In 2020, the federal government’s quarantine authority is largely limited to containing the spread of infectious diseases from other nations at the U.S. border. Any decision to isolate or quarantine individuals within American communities would come from a more local authority.

“States are the place where public health is practiced and where quarantine and isolation would be implemented,” Remington said.

In Wisconsin, these powers are devolved further to local units of government thanks to the state Constitution, which grants counties and municipalities significant latitude to self-govern. Wisconsin and states with similar governance structures are known as “home rule” states.

As a home rule state, “it is up to local public health departments to determine if or when there is to be quarantine or isolation of a person or a number of people with an infectious illness,” wrote Jennifer Miller, a spokesperson for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, in an email to WisContext.

Miller pointed to two state statutes that address these situations, one that explicitly provides isolation and quarantine powers to local health departments, and another that forbids individuals from violating isolation or quarantine orders.

“A decision to quarantine or isolate a person or group of people is a thoughtful process that balances the health and safety of the general public with the health, safety and constitutional rights of the patient in question,” Miller added.

This process begins at the county or municipal level in Wisconsin, but would likely include input from state authorities and possibly from federal agencies like the CDC, depending on the seriousness of the situation.

Public health authorities in Wisconsin’s largest city say they are ready to impose quarantines or isolate patients stricken with 2019-nCoV if they have to.

“While it’s not our preferred approach, the [Milwaukee Health Department] has issued isolation and quarantine orders in the past and is prepared to do so, if necessary, to prevent the spread of 2019-nCoV,” wrote Lindsey Page, infectious disease program manager for the City of Milwaukee Health Department, in an email to WisContext. Such orders in the recent past have been associated with tuberculosis, measles and other cases of communicable diseases once common but now rarer in Milwaukee and the U.S.

Page said the health department would first consider “less restrictive means that could accomplish the same public health goals,” such as working with at-risk individuals to voluntarily restrict their movements if necessary. She said that in the event the department should choose to implement an isolation or quarantine order, anyone affected would be provided with shelter, food, water and other necessities, and that the department would work to protect their dignity and privacy.

“People under public health orders must be treated with respect, fairness and compassion,” she said.

The CDC has published interim risk assessment guidance for local public health authorities wrestling with these decisions in the case of 2019-nCoV. As of Feb. 3, 2020, the CDC considered individuals at high risk of contracting the virus if they live in the same household as someone with a confirmed infection and haven’t followed home-isolation guidelines, or if they have recently traveled from China’s Hubei province.

Individuals deemed at medium risk include anyone who has had “close contact” with someone who has a confirmed 2019-nCoV infection. This includes airline passengers within six feet (or roughly two seats) of an individual with symptoms like fever or cough and a subsequent confirmed infection. It also includes individuals in a household with a confirmed infection who consistently follow home isolation precautions, as well as anyone who has recently traveled from mainland China.

Page said the Milwaukee Health Department “will restrict movement on individuals for approximately 14 days that fall into the high and medium risk categories and will issue isolation and quarantine orders if deemed necessary.”

Local health departments in Wisconsin are receiving information about individuals deemed at high or medium risk from the CDC via the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System.

In Dane County, which has a population of international students from China mostly affiliated with the University of Wisconsin-Madison, public health officials declined to comment on any action plans that may include the use of quarantine or isolation orders — a Public Health Madison & Dane County spokesperson cited a lack of time amid pressures to monitor the 2019-nCoV outbreak as it unfolds. The university, meanwhile, is providing ongoing updates and guidance to members of the campus community.

A key part of weighing a quarantine order is determining the potential risks to the public if a quarantine were not imposed. In the case of newly emerging diseases such as the novel coronavirus, Remington said public health officials may be more inclined to err on the side of caution and impose restrictions on movement while epidemiologists perform the important work of determining how contagious and deadly the disease is.

“I think in those instances, governments and public health agencies are going to be a bit more cautious than if we were dealing with measles or rubella or whooping cough, which are well-known and have long standing evidence to show what types of public health interventions work,” he said.

However, Remington warned that an overly cautious response — such as in the form of the widespread quarantines imposed in China — risks backfiring by heightening public anxiety and straining a population’s trust in public health authorities by overzealously curtailing basic freedoms.

“It’s a very difficult balancing game between using these powers judiciously and effectively but not abusing them,” Remington said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us