The Disconnected Discussion About Mental Illness And Mass Shootings

In the aftermath of tragedy, people often go searching for answers: How could this happen? Why did someone do this? Could this have been avoided?

February 27, 2018

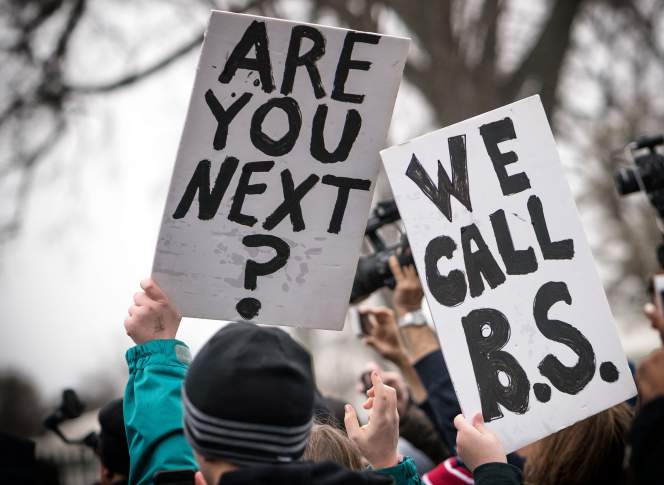

Parkland, Florida school shooting protest in Washington D.C.

In the aftermath of tragedy, people often go searching for answers: How could this happen? Why did someone do this? Could this have been avoided? After 17 students and faculty members at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida were shot and killed on Feb. 14, 2018, people around the United States once again asked these questions. Gun policy quickly became central to discussions about finding answers, but the issue of mental health and the nation’s system for addressing rose to the top of the docket as well.

“This is a mental health problem at the highest level,” said President Donald Trump at a news conference following the November 2017 mass shooting at a church in Sutherland Springs, Texas. He reiterated this position after the Parkland shooting, and in Feb. 23 remarks to the Conservative Political Action Conference, addressed both guns and mental health

“We don’t want people that are mentally ill to be having any form of weaponry,” Trump said. “We have to be very strong on that.”

Along with Trump, other firearms advocates and elected officials made connections between gun access and mental health in the wake of the Parkland shooting.

“People who are crazy should not be able to get firearms,” said National Rifle Association spokesperson Dana Loesch at a Feb. 22 town hall discussion in Florida hosted by CNN.

Speaker Paul Ryan, a Republican who represents Wisconsin’s 1st congressional district, insisted that enforcement of laws related to firearms access and mental health, rather than new gun restrictions, is key to preventing gun-related tragedies.

“We have to make sure that people who are mentally unstable — and we just passed a recent law on this — don’t have the ability to go do this,” said Ryan Feb. 24 at a Republican Party event in Pewaukee. He made similar comments following the October 2017 massacre in Las Vegas.

In Wisconsin, the state Department of Justice is required to report information on individuals barred from owning firearms to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System. That includes people with “mental health commitments where the individual is found to be a danger to self or public safety,” those in “treatment for and commitment of an individual incapacitated by alcohol or suffering from alcoholism,” “individuals who have a guardian appointed for them,” or those with a protective services placement or placement order, according to the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, a national policy group in support of increased gun regulation.

However, as noted by Politifact Wisconsin, the aforementioned requirements only account for a small portion of people with mental illness, and don’t cover those who might become violent but are not diagnosed.

Governor Scott Walker issued a statement following the Parkland shooting that likewise cited mental health. “We have already put new funding in the state budget for mental health services in our schools after hearing about concerns from superintendents, principals and teachers at listening sessions across the state,” he said.

A narrative emphasizing the role of mental health in mass shootings has been repeated by the president, legislators and interest groups. But research has found that mental health does not play a major role in gun homicides or mass shootings, and making such connections is baseless.

In a Feb. 16, 2018 interview with Wisconsin Public Television’s Here & Now, National Alliance on Mental Illness Wisconsin executive director Nate Schorr addressed the situation in simple terms: “People with mental illness are no more likely to perpetrate violent crimes than the general population.”

Mental illness is common in the U.S. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, an estimated one in six American adults live with a mental illness. Wisconsin is no stranger when it comes to addressing challenges related to mental health — for example, Milwaukee County has had the highest rate of psychiatric readmission in the U.S., while across the state youth continue to struggle with mental health challenges.

Wisconsin has been a leader in the leader in the mental health arena in some ways, said Schorr, whose educational and advocacy group was founded in Madison in 1977. He noted that Wisconsin has made advancements in crisis intervention training, which educates law enforcement officials about how to better understand how to serve and interact with people experiencing a mental health crisis.

Despite the mental health challenges Wisconsin and the nation as a whole face, Schorr said changing that system is unlikely to stop any mass shootings.

“In fact, people with mental illness are more likely, significantly more likely to be victims of violent crimes, and particularly with gun violence as it relates to suicide attempts,” he said.

Schorr explained that when tragic actions like the shooting in Parkland are perpetrated, people look for any way to make sense of the situation. But by blaming a tragedy on mental illness, those who struggle with their mental health are further stigmatized.

“I think that it’s important to frame the conversation in a way that isn’t demonizing people with mental illness,” he said.

In a statement on the Parkland shooting, NAMI Wisconsin asked its supporters to advocate four steps to help address mental health among students. Its recommendations include increasing mental health awareness and availability of counselors in schools, as well as providing the tools necessary to have conversations mental illness.

In an Feb. 23 interview with the New York Times‘ “The Daily” podcast, psychiatrist Dr. Amy Barnhorst noted only about 4 percent of community violence — a type of traumatic action that includes mass shootings — is attributed to mental illness. Vice chair of community psychiatry at the University of California, Davis, Barhorst said there’s a major difference when it comes to actually diagnosing a mental illness in an individual and simply seeing traits in someone. Many mass shooters, she said, share a common behavioral pattern, but this doesn’t necessarily mean they have a diagnosable mental illness.

“A lot of them are just really bitter, angry, resentful young men who have similar histories of social isolation. They’ve been bullied, they’ve harbored revenge fantasies, they have an entitlement toward social standing, toward attention from women. They feel like they’re not getting the popularity and the attention they deserve,” she said.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us