The Casual Culture Of Violence Against Women

U.S. culture steeps people in casual references to rape and domestic violence, and these attitudes end up deepening the trauma victims of these crimes face.

January 10, 2017

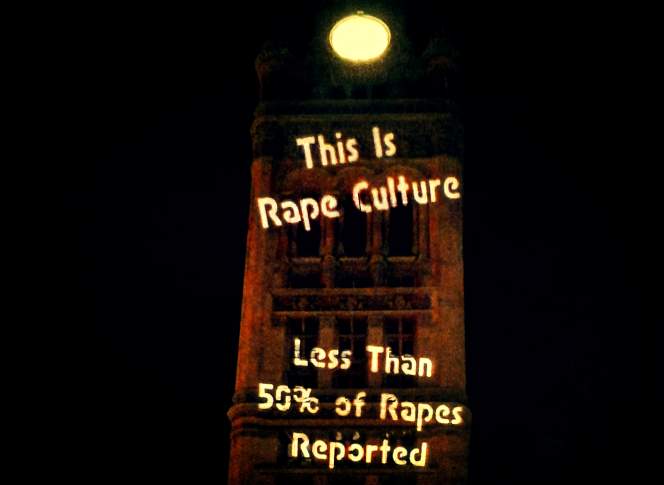

Rape culture light projection on Milwaukee City Hall illustration

U.S. culture steeps people in casual references to rape and domestic violence, and these attitudes end up deepening the trauma victims of these crimes face. Incidents like a sexual assault and kidnapping reported in Marathon County in December may seem like horrific aberrations met with swift justice, but they take place against a cultural backdrop that normalizes violence against women and makes it harder for victims to put their lives back together.

Jane Graham Jennings, executive director of The Women’s Community in Wausau, and Paul Clarke, a criminal justice instructor at Northcentral Technical College’s School of Public Safety, discussed this issue on the Jan. 5, 2017 edition of Wisconsin Public Radio’s Route 51.

That backdrop is often referred to rape culture, which the Marshall University Women’s Center defines as “an environment in which rape is prevalent and in which sexual violence against women is normalized and excused in the media and popular culture.”

As Route 51 host Glen Moberg mentioned in the interview, some people dismiss the concept of rape culture, because sexual assault is a crime and convicted rapists are often vilified. But both Clarke and Jennings illustrated how commonly held attitudes and popular entertainment casually treat violence against women, and how discussions about sexual assault can devolve into blaming the victim.

From a criminal-justice perspective, what the victim did is irrelevant, said Clarke, who investigated sexual assaults in his earlier career as a police officer.

“If you had a car and it was stolen, we probably wouldn’t be having a conversation about where you parked it or ‘Why’d you have such a nice car?’ … [or] ‘It’s the number-one stolen car in America, why were you driving that thing?'” he noted.

Jennings said that all sorts of denial can kick in when someone is accused of sexual assault. Moberg cited examples of powerful, high-profile people like President-elect Donald Trump, who was caught up on tape bragging about sexual assault, and former President Bill Clinton, who has been accused of it, though Jennings noted the issue is universal and transcends partisan politics.

“We rationalize those things away so that we can support our own beliefs about something because we like that person,” she said.

Denial is just as relevant when an assault involves an accusation against a family member, friend or neighbor.

“We don’t understand or want to accept the fact that people will do this by intent,” Jennings noted. “People who commit these crimes are people who we know and care about.”

People can tend to misunderstand the basic nature of sexual assault and domestic abuse, and overlook the fact that these crimes leave lasting, profound psychological damage, Jennings explained. To illustrate how often people minimize the harm done to sexual assault victims, she pointed to the case of convicted rapist Brock Turner, whose father lamented that his son had to go to prison over “20 minutes of action.”

“When someone is sexually assaulted, the thing that we believe to be true, which is ‘I have control over one thing myself’ … that control has been stolen, and it changes the entire dynamic of the way that victim views the world,” Jennings said.

Above all, it’s about power.

“This is not a crime about passion and ‘I’m overwhelmed with lust,'” Clarke said. “It’s a crime about taking power and control away from people.”

That power dynamic is a big part of what makes domestic violence situations incredibly dangerous and at times fatal. One service that Jennings’ organization provides is helping women make a plan for staying safe while in the process of leaving an abusive partner.

“In domestic violence, yes, the most dangerous time for someone is when they have decided to leave or after they have left, because the tie of control has been broken, and the person who is hurting them and wants to control them is saying, ‘I will control you and you can’t leave me,'” she said.

Of course, victims seeking justice are subjected to yet more trauma, and that in turn can deter their reporting of sexual assaults. Clarke said that law-enforcement officers — obligated to treat people as innocent until proven guilty — should treat victims with an attitude of believing them and trying to help them.

“Not being believed is the biggest factor that hampers and halts someone’s recovery,” Jennings said.

Much of the cultural conditioning around sexual assault begins in childhood, Jennings explained. For instance, bullying might not always have a sexual component, but it normalizes the idea of touching another person without their consent. And when children report sexual assault to adults, they tend to be dismissed, often because the perpetrator is someone respected within their family or community. That’s another example, she noted, of the inclination toward denial.

Detailing prevention efforts by The Women’s Community, Jennings pointed to childhood as an important place to try and break the cycle.

“What we tell children is, you keep telling until some adult listens,” she said.

Jennings stressed that all 72 counties in Wisconsin have resources for victims — the Wisconsin Eastern Probation Office has compiled a list of rape crisis centers, and the Wisconsin Coalition Against Domestic Violence provides a directory of its members and their services.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us