The Broadband Gap Leaves Rural Wisconsin Behind In The COVID-19 Crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare many of the ways in which poor internet service can make rural residents less productive and more isolated than their urban counterparts.

March 24, 2020

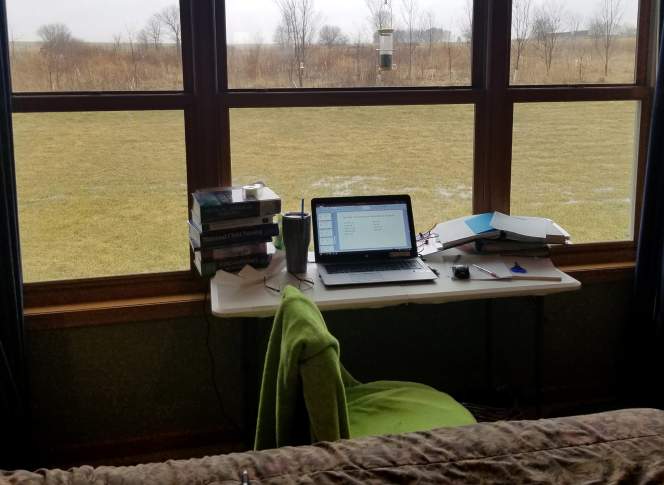

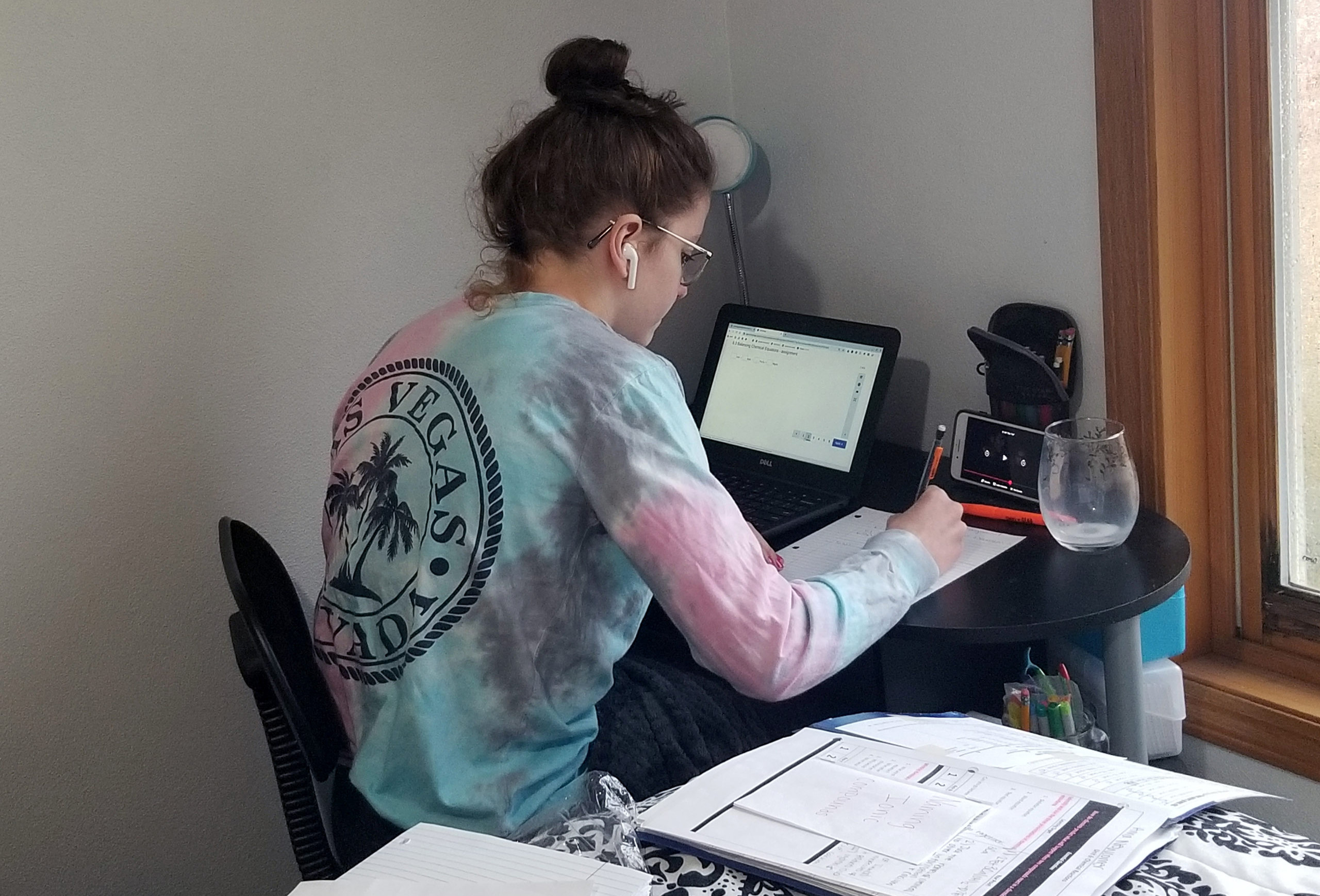

Traci Newcomer home office in Monroe

The Newcomer household near Monroe is fairly typical for rural Wisconsin. It is surrounded by cornfields. The nearest neighbor is a quarter-mile down the road. And the internet is terrible.

Now the coronavirus shutdown has put serious stress on the family. The teenagers struggle with the drip of internet service to do their homework while school is closed.

Their mother, Traci Newcomer, 41, teaches nursing at the nearby Blackhawk Technical College campus in Janesville, and classes have now moved online. Because their internet service is so poor, she cannot teleconference at home. Newcomer must drive 10 minutes to the parking lot of the college’s Monroe Campus to use the Wi-Fi there.

“Today I put the computer on my passenger side seat and turned sideways and conducted my class that way,” she said, prompting chuckles from her students before she got down to business.

Back at home, Newcomer and her two children have to alternate who can connect to the Wi-Fi. And that is when they are getting any reception at all.

“Right now, three of us are very dependent on the internet and can’t get accomplished what we want to accomplish in a big chunk of our day,” she said.

School and work are just a couple of the areas in which reliable, fast internet is needed as Wisconsin hunkers down to keep COVID-19 at bay. Increasingly, health care professionals see patients online to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus. And everyone is hungry for the latest news as this worldwide emergency continues.

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare many of the ways in which poor internet service can make rural residents less productive and more isolated than their urban counterparts.

Already, Wisconsin lags behind the national average in broadband coverage. An estimated 43% of Wisconsin’s rural residents lack access to high-speed internet, compared to about 31% of rural residents nationwide, according to the Public Service Commission of Wisconsin.

“We have such a long ways to go,” said state Sen. Jeff Smith, D-Eau Claire, who has tried unsuccessfully to increase the state’s investment in broadband. “And now this is going to be one of the things that comes out of this [crisis] when we’re all done: ‘I guess we shouldn’t have dragged our feet for so long, and now we’d better get serious about it.'”

Many people in urban areas likely take for granted how much they use fast internet. Video chatting. Online banking. Amazon Prime.

Now imagine life if the internet trudges along and frequently conks out. That is what rural businesses and the communities where they operate often face in Wisconsin. And during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of those country-living people, children and adults alike, now have to conduct their daily lives from home.

Smith lives about five minutes outside of Eau Claire in the town of Brunswick, where he and his wife Sue live on a farm with horses, chickens, dogs, cats and a llama. Smith said his internet speeds are so bad he can hardly stream anything, and websites take a long time to load.

“This is the new public utility,” Smith said, “and everyone has to have it.”

State investment low

Through programs like the FCC’s Connect America Fund, the federal government has granted about $1 billion since 2015 to help service providers build and maintain voice and internet infrastructure in Wisconsin.

Some of that service is not yet online; providers have up to six years to offer broadband. And the program only requires an outdated speed of 10 megabits per second for downloading, although an FCC spokesperson said nearly all of the funded projects will offer the federal definition of broadband, 25 megabits per second to download, and 3 mbps to upload.

Between 2013 and 2019, the state of Wisconsin provided $20 million in grants to private and public entities and cooperatives to provide high-speed internet in unserved and underserved areas. In 2020, funding greatly expanded to $24 million in broadband expansion grants.

But critics say even the new budgeted amounts are rain drops in an empty pool compared to what is needed to achieve significant coverage across the state. And the state grant rules do not set speed requirements in a rapidly accelerating digital landscape.

“That’s pretty meager,” said Anita T. Gallucci, a Madison-based attorney who advises municipalities on telecommunications issues. The needed speed, not to mention what will be required in the future, is “way beyond that,” she said.

As technology and stream quality advances, internet speeds have to keep up. For example, for many new TVs with a 4K stream, Netflix requires at least an 18 mbps download speed and at least 50 mbps for multiple users, according to Consumer Reports.

Telecommunications companies have relatively little problem providing broadband to urban areas, because cities and towns are densely populated. For-profit businesses happily make the initial, and often heavy, infrastructure investment, because they have a large customer base.

But sparsely populated areas are not enticing for private companies. The cost of burying miles of fiber optic cables — one of the fastest and most reliable ways to deliver the internet — can be prohibitive. Rural residents instead might need to rely on less dependable forms of internet delivery by satellite or wireless. And those can be affected by factors including weather, trees and topography.

Other state governments have stepped in more forcefully. About 16% of rural residents in Minnesota lack access to high-speed internet — about one-third as many as in Wisconsin. That is in large part because Wisconsin’s western neighbor has invested heavily in rural broadband.

From 2014 to 2019, Minnesota spent about $108 million to expand high-speed internet, according to Eric Lightner, a spokesman for the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development. That is more than five times what Wisconsin spent during a comparable period.

The politics of providing internet

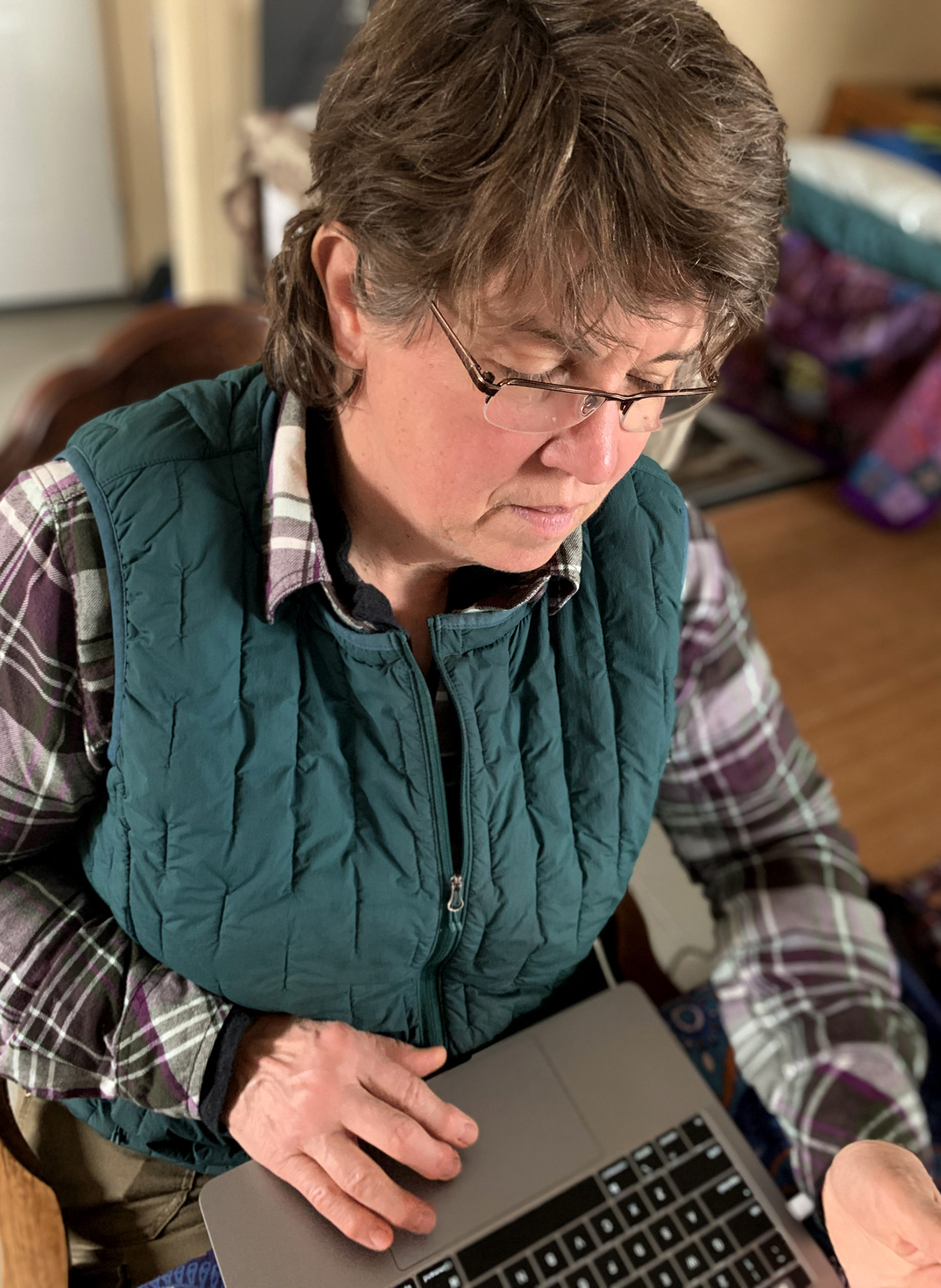

Kathleen Vinehout, a former state senator and Democrat who lives in the ruggedly beautiful but reception-resistant Driftless Area of southwestern Wisconsin, said she sometimes drives to the parking lot of the American Legion hall in Alma to get Wi-Fi.

She echoed many from her party in criticizing Republicans, who controlled state government from 2011 through 2018, for not funding rural broadband.

“The money they were putting in was only a token,” Vinehout said. “It was only a soundbite. It had nothing to do with the amount of money that needed to be invested to make a difference in people’s lives in this state.”

In 2011, the administration of then-Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican, actually returned $23 million in federal stimulus money intended for broadband expansion to schools, libraries and government agencies. Administration officials said the grant requirements were too stringent. Walker declined to comment through a spokesperson.

Last year, Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, proposed adding nearly $75 million to the Broadband Expansion Grant Program in his 2019-20 budget. The powerful Joint Committee on Finance, which writes the budget and is controlled by Republicans who have majorities in the Legislature, scaled that back to $44 million.

“There’s never enough money to do what you need to do,” said state Sen. Luther Olsen, a Republican from Ripon and joint finance vice chairman who has worked on the rural broadband issue.

Olsen said he has good internet coverage at his home in Ripon, but his cabin in Wautoma uses less reliable satellite internet, at slower speeds.

“It’s one of those things where we’re not going to get the problem solved as fast as everybody would like, but at least we’re working towards that outcome,” Olsen said.

Gail Huycke is a community development specialist with the University of Wisconsin-Extension. Huycke, who focuses on broadband access, lives in Phillips in the northern part of the state. Her internet runs slowly, about 8 to 10 megabits per second.

Minnesota’s rural broadband coverage is better than Wisconsin’s, Huycke agreed, but noted that the state also has higher sales and income taxes.

“I think that’s a trade that you have to make,” she said.

In fact, while Wisconsin has fallen behind in areas like rural broadband, Republicans are quick to boast that the tax burden has fallen to its lowest level in at least 50 years.

The finance committee rejected Evers’ attempt to raise the minimum speeds required for providers to receive state grants for providing internet. And the committee eliminated the governor’s proposed statewide goal of achieving internet speeds that match or surpass the federal definition of broadband by 2025.

In the 2019-20 legislative session, Jeff Smith introduced several bills to improve service, including investing more in broadband expansion grants. But the Republican majority ignored the Democratic state senator’s bills and they went nowhere.

The effort to improve access did get a boost, however. Wisconsin will end a tax on telephone companies installing internet infrastructure. That is thanks to a bill introduced by state Rep. Romaine Quinn, R-Barron, that Evers signed into law on March 3. Companies that began as internet companies do not have to pay the tax.

“This bill is another important tool for our local providers,” Quinn said in a press release. “In combination with historic investments in Wisconsin’s Broadband Expansion Grant program, Wisconsin is truly creating an innovative environment for making sure that everyone in our state has the internet service they need.”

Attorney Anita T. Gallucci said if the move helps rural broadband expansion, that is great, but she called the bill “small potatoes.”

On March 24, 2020, a bipartisan group of U.S. senators, including Wisconsin’s Democratic Sen. Tammy Baldwin, introduced a $2 billion bill to compensate small broadband providers for offering free or discounted rates to low-income families during the pandemic.

Government steps in

If private companies will not provide broadband service, municipalities can build their own systems. But that can be a heavier lift than some communities want to handle.

The city of Madison released a plan in 2018 to build a citywide, high-speed fiber internet network but shelved it when learning it could cost more than $173 million.

Reedsburg’s utility, owned by the city but operated independently, built and maintains its own fiber network. Like any other telecommunications company, the utility must provide customer support and, essentially, cable guys. The city delivers rapid 1,000 mbps download and upload speeds for between $45 and $50 a month.

“It’s a lot of work,” said Brett Schuppner, the general manager of the Reedsburg Utility Commission. “I just don’t see other utilities willing to take that on, unless their elected officials are going to push it.”

In 22 years of providing internet service, the Reedsburg utility has made enough money to pay its bills and turn enough of a profit to invest in and grow its system, Schuppner said.

“We’re not-for-profit,” he said, “but we’re also not-to-lose-money too.”

Sun Prairie Utilities built its own fiber network in the late 1990s to connect the schools and city buildings as well as some businesses, later extending to residences. The city sold it in 2017 to TDS for about $2.9 million, allowing Sun Prairie to turn a small profit on its investment.

From 2000 to 2015, the city of Sun Prairie and the Sun Prairie School District each saved an estimated $2 million over the cost of private service, which was slower, said Rick Wicklund, the city’s utility manager.

The city of Superior announced in February 2020 that it is also considering building its own broadband infrastructure, but one on which private companies would be able to provide the service and compete against each other.

Bringing Wisconsin up to par

There are ways Wisconsin could catch up. Wisconsin could invest more heavily where private companies are reluctant to go.

State Sen. Jeff Smith also argues for a speed requirement when doling out state grants. Minnesota requires grant recipients to deliver speeds of at least the federal minimum, with a goal of reaching 100 megabits per second for downloading and 20 megabits per second for uploading by 2026.

While Wisconsin does not have a speed requirement in awarding grants for private companies to build broadband, speed is a factor when the Public Service Commission considers which proposals will receive state money, said Matthew Sweeney, a spokesperson for the agency.

State Sen. Luther Olsen said a cheaper alternative to buried fiber optic cable would be to deliver internet by white space, the extra capacity in TV broadcast bands. Such service is much slower than fiber networks.

On March 19, 2019, the FCC adopted a series of changes to make it easier to use TV white space to provide internet service in rural areas.

Co-op retools to provide service

Cooperative organizations also have stepped up in rural areas to lay fiber and provide internet service where private companies have not.

Cochrane Co-op Telephone in Buffalo County along the Mississippi River started as a telephone company for farmers in 1905. It now provides the communities of Cochrane, Buffalo City and Alma with high-speed internet delivered through fiber optic cable. The co-op offers speeds as low as 25 megabits per second for $50 per month, and as high as 1,000 mbps, the same as Reedsburg, for $200 per month.

Brett Schuppner, the Reedsburg utility chief, said government should focus its support on providing high-speed systems. “If public funds are being used,” he said, “it should be to provide a service that’s going to meet the needs for a long time.”

UW-Extension’s Gail Huycke agreed, citing a quote from hockey legend Wayne Gretzky, who said his father told him to skate where the puck is going, not where it has been.

“We need to think about broadband,” Huycke said, “like Wayne Gretzky.”

Peter Cameron is managing editor of The Badger Project, a nonpartisan journalism nonprofit based in Madison. He reported this story under the direction of Wisconsin Watch managing editor Dee J. Hall. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Passport

Passport

Follow Us