Tackling Urban Heat Islands Goes Beyond The Big City

City centers typically are hotter than suburbs, which in turn tend to be hotter than rural areas, controlling for other factors. The more developed and densely populated an area, the more buildings, asphalt and other solid surfaces amplify and absorb the heat of the sun, usually with fewer plants to help cool things down.

December 6, 2016

Screenshot from UW-Madison Water Sustainability and Climate mini-doc on urban heat islands

City centers typically are hotter than suburbs, which in turn tend to be hotter than rural areas, controlling for other factors. The more developed and densely populated an area, the more buildings, asphalt and other solid surfaces amplify and absorb the heat of the sun, usually with fewer plants to help cool things down. This dynamic is a phenomenon known as an urban heat island.

Elevated heat levels in any location people live have direct and indirect consequences on health and the environment, from an increased risk of heat stress to more use of air conditioning, which increases energy consumption and production of air pollutants like ground-level ozone.

Facing increased temperatures, however slight they may seem on an incremental basis, people living in urban heat islands can experience impacts of climate change sooner and more intensely than others. However, this phenomenon does not contribute to temperature trends related to global climate change, outside the long-term role of elevated greenhouse gas emissions from cars in urban traffic or from power plants that fuel those air conditioners with coal- or gas-generated electricity.

The urban heat island effect generally becomes more pronounced the more dense and populous an area is. However, more Americans live in mid-size cities — like Richmond, Reno, or Raleigh-Durham — than in big, very dense metropolises like New York, Chicago or San Francisco. But mid-size cities are expected to grow over the next several decades, including those in Wisconsin, as more Americans move from rural communities to more urbanized areas.

This demographic makes Madison a useful subject for studying urban heat islands. Sure, Wisconsin’s capital city can be seen as an economic and political outlier, thanks to its preponderance of public workers, liberal voting patterns and no small amount of hometown exceptionalism. But as a growing city of just under 250,000 people and metro area of around 600,000, it faces environmental decisions typical of American cities: How to support housing and transportation for more people, how to balance new development with the preservation of environmental quality and open space, and how to prepare for extreme weather and other climate change impacts.

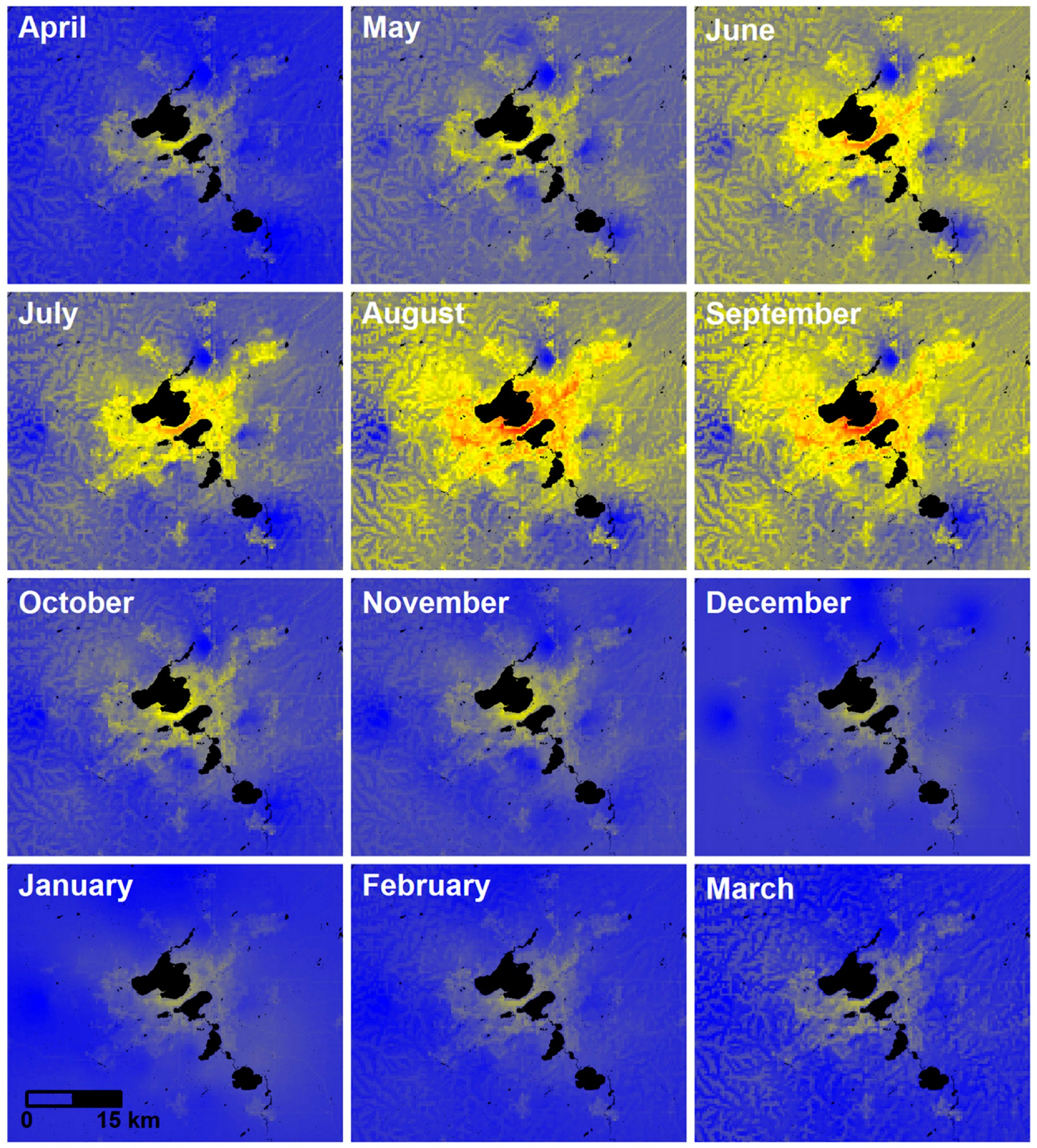

A recent round of research on Madison’s urban heat island is being conducted in the context of Yahara 2070, a project that aims to understand the environmental future of the region and its Yahara River Watershed. University of Wisconsin-Madison agronomist Christopher Kucharik discusses Madison’s heat island in a mini-documentary created through the Yahara 2070 project’s coordinators at UW-Madison’s Water Sustainability and Climate Project.

But just comparing temperatures in a city to temperatures in a nearby rural area isn’t enough to understand heat islands. Temperatures can also vary significantly within an urban area.

One study Kucharik led found that recorded temperatures in Madison’s central, most densely populated area — known to locals as the isthmus — are higher than those at Dane County Regional Airport, which is located only five miles away and still has a lot of developed, populated areas adjacent to it. (This may offer some fuel for people who scoff at meteorologists for reporting weather conditions at a city’s airport.)

During the summer 2012 heat wave in the Midwest and much of North America, the Madison metro area as a whole experienced temperatures above 90 degrees Fahrenheit for 39 days. But the city’s downtown experienced nearly 50 days over 90 degrees — illustrating how much temperatures can vary even within a relatively small geographic zone. The data, gathered from 151 sensors placed throughout the Madison area, offers some foresight for a warming world.

“It was very typical of what we might expect the mean climate to be like in, let’s say, 50 to 75 years in the city of Madison,” Kucharik said in the video. Looking forward, he expressed interest in building on this research to ask more questions about how urban areas will be affected by to heat waves in the future.

Making weather data more abundant

Though every city has its own geography and will experience heat islands differently, Kucharik thinks other mid-sized cities could learn from his research in Madison, and perhaps take advantage of new technology developed in the four years since he started the monitoring project. A postdoctoral researcher, Jason Schatz, had to climb up a lot of utility poles around Madison to physically download data from each sensor the project used. Someone starting a similar effort now would have better tools to work with.

“I think in today’s age, with all these new sensors and smartphones and all this new technology that can measure things remotely and beam that data up through a 4G or Wi-Fi network, I think the future’s pretty bright for smart cities,” Kucharik said in an interview.

He envisions that abundant data could fuel real-time monitoring software and communication, with direct uses for city residents, power companies and municipal services like snow removal.

“To have it at a really fine scale would be pretty cool,” he added. “It’s hard not to envision that being the norm in another 10 years.”

Decision-making fueled by immediately available weather data in localized areas of cities can also have an impact on the broader ecosystem. For instance, in an urban heat island, soils might retain warmth later in the year than in less populated areas, meaning that snow could melt faster. Armed with that data, local governments could reduce the amount of salt they place on roads. In turn, less of that salt would run off into lakes, rivers and groundwater, reducing its impact on water quality (including chemical changes related to corrosion in pipes).

“You could imagine how hard of a sell that would be to a streets superintendent,” Kucharik said, “I probably say that with a bit of humor, as I can only imagine how difficult it is for them to plan.”

Researchers have developed a number of methods to cool things down a little bit in cities. If a building has a black roof, replacing that with a white roof will reduce the amount of heat it absorbs and the energy needed to cool it. “Cool pavement”replaces conventional asphalt with various materials that reflect more sunlight and avoid soaking up more of its heat.

In the video, Kucharik even mentions the possibility of interspersing small parks throughout dense areas, so that the cooling effect of plants is more widely distributed. This proposal ties into a central theme of the Yahara 2070 project: How to parcel out different uses of land in order to reap all the benefits people seek to gain from their ecosystems, but without putting too much pressure on any single part. A small park might not make a huge difference in temperature on a 100-degree day, Kucharik said in an interview, but there might be benefits to giving urban residents more places to escape to when it’s extremely hot.

Making policies that cool cities down

Heat island effects have largely been studied in very large cities, so there is a need to examine them more deeply in mid-sized ones, said Hashem Akbari, a professor at Concordia University in Montreal who founded Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory’s heat island group in 1985 and ran it until 2009. In fact, the study of the concept began in London in the late 1800s, he said.

“We have mostly focused on areas where data easily exist so we can use those data to do comprehensive studies,” Akbari said. But his work has been more centered on solutions, particularly on developing better materials for “cool” roofs and road surfaces, and working with policymakers to get people to use those materials.

Over the years, Akbari has seen a growing level of interest from governments and businesses in adopting the solutions he’s helped develop. Building owners can save a lot of money by making their heating and air conditioning more efficient, and a building with a “cool” roof absorbs less heat, lowering costs even more. Plus, roofs and roads are infrastructure that must be replaced every so often anyway.

Akbari would like to see more urban areas take these steps.

“With all the success we’ve had in the last 30 years, there’s still a lot of cities that have not adopted cool-cities programs,” he said. “The use of cool roofs and cool pavements in the southern part of the United States is more accepted, but in the central or northern parts of the U.S., there’s still a lot more needed to be done.”

It’s partially an issue of perception. Akbari said that many people still think that cool roofs and roads are only beneficial in very hot places like the southeast U.S., but he contends that they are beneficial just about anywhere.

“In cold climates, a place like Wisconsin, in the wintertime, there is not much sun, and to start with the days are much shorter, and most roofs have snow cover on the roof,” he said. “So having a cool roof would not have much a negative impact during the winter time, and having a hot roof would not have much of a positive impact.”

Additionally, people in the northern U.S. are more likely than people in the south to live in homes without air conditioning, especially if they are poor or elderly. When a heat wave hits a city in more northerly climes, people living in older buildings with poor ventilation are highly vulnerable to heat stress.

“It is crystal-clear from the data in the U.S. and Europe that most of the mortalities occur in old buildings, for old people who happen to be living on the upper floor of the building,” Akbari said. “A cool roof may have saved their lives.”

Although a fan of cool roofs and roads in particular, Akbari sees urban heat islands as an issue that requires a comprehensive solution, including elements like using trees to shade buildings from the outside. He said that since all people contribute incrementally to climate change and heat islands, everyone needs to work together to address them. And he puts an emphasis on bringing scientists, policymakers, environmental groups and businesses to the table to help cities cool themselves down in a systematic way.

“I think that the issue here is mostly an implementation issue, and trying to adopt policies or try to recruit leaders within the urban area who can develop programs for cooling the urban areas as a whole,” Akbari said. “Mayors, city councils, public and industrial leaders — they all play important roles.”

Passport

Passport

Follow Us